My friends John and Helen and I toasted my departure with wild blackberries. Our farewells said, I climbed aboard KIMCHI, the 12′ Salt Bay skiff I’d built with John’s guidance. I pulled on the oars, slipping away from the dock into the John Day River near Astoria, Oregon. The sky was a gray sheet and the water like glass, murmuring softly as KIMCHI picked up speed.

I’m really a sailor, not a rower. But that morning the weather decided that, like it or not, I was going to be a rower. I didn’t mind, since there was no sun to warm me and I wanted to work up an appetite. It was flood tide, and the John Day River, which feeds into the Columbia just 12 miles before that broad river reaches the Pacific, was flowing in reverse. Once I was on the Columbia itself, the tide would be in my favor as I headed east, but I had a mile to row against a nearly 2-knot current before I reached the John Day’s mouth at Cathlamet Bay. A derelict railroad bridge marked the gateway between the two, and with a final sprint I pushed through the narrow channel between its pylons and onto the edge of the estuary’s 5-mile-wide expanse.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

Leaning on the oars, I drifted with the now favorable current, slowly making my way to Portland, and my home. KIMCHI slid over submerged marshland, as minnows and weeds alike swayed to let her pass. They moved with a sleepy lack of concern, as if they would not have moved at all if the water displaced by the hull didn’t push them aside. I was glad for the stillness, catching my breath while the river itself was inhaling deeply.

After drifting a while, I set to rowing again. As I left the shallows and began traveling the channels between the sandbars and the southern bank of the river, the small black head of a harbor seal popped up from the water a few hundred feet from the boat. The seal followed me most of the morning, resurfacing every few minutes, its head swiveling like a periscope until it caught sight of me again. Each time, its dark, marble eyes held me in an unwavering gaze. Then I would blink and the seal would vanish seamlessly back into the water.

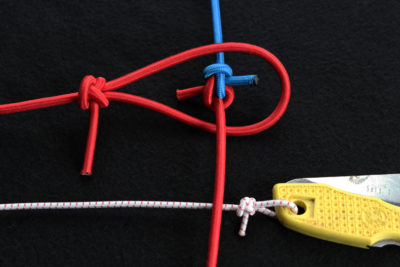

The morning passed with steady rowing on a quiet river. Around noon, the sun came out, burned the fog away, and brought the wind. It happened in a matter of minutes, and the world of gray was suddenly light blue. I stowed the oars, keeping them in the oarlocks and sliding the handles all the way to the stern where I strapped them to the quarter knees. I unfurled the bundled sail and spars, stepped the mast, and set the boom and sprit. A quick haul on the boom vang and the snotter to snug them up and cleat them, and in 60 seconds I had the sail flying. I settled into the stern, took the tiller and the sheet, and KIMCHI scooted along in the building breeze.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorHer sail set for the midday breeze, KIMCHI rests on the beach at Jim Crow Sands. To the northeast, across the shipping channel, lies the Washington shore. Most of Jim Crow Sands is dredge spoil, pumped up from the bottom of the channel.

Within an hour it was blowing 7 or 8 knots from the northwest. The landscape had a new skip in its step, trotting past me where before it had ambled. As I sailed along, I spotted unusually bright white sand on the bank of an island and turned north toward it, sheeting in from a run to a beam reach. KIMCHI entered the shallows around Jim Crow Sands, a mile-long sandbar that stretches east from Pillar Rock Island. Ten yards offshore I slid forward and pulled the leeboard up from the starboard side. The rudder, rigged with a bungee downhaul that allows it to kick up, could fend for itself.

When the boat eased to a stop, I stepped off into a few inches of water and my right leg suddenly plunged up to the knee in the sand, water erupting around it with the release of trapped air. I nearly fell on my face, my left leg still in the boat at ground level, the right buried in the porous sand. After the initial shock, I rolled up my pants and stepped out of the boat with my left leg. The ground held firm, so I pulled my right leg out of the sand and stepped with it again. Everything seemed fine. I placed my third step with more force and my leg sank to the shin in a flurry of bubbles. When I finally reached solid ground, I set off running down the beach, much to the disapproval of the Canada geese and ducks attempting to enjoy their respite on the shore. They squawked, waddled, and flapped a few disorderly wingbeats to put some distance from me. I thought better of disturbing the birds and returned to the boat. The sun had burned the clouds away entirely, and a fresh northwesterly rattled the sail and spars as the boat rested on the shore.

Departing Jim Crow Sands, I decided to avoid the shipping lanes to the north of the island and take a back route around a cluster of scrub-covered islands to the east. My chart showed that the channels between them would become shallow but clearly passed through to the river. With an 8-knot tailwind pushing KIMCHI, I sailed down the first major artery, whipping past a row of ramshackle houseboats along Woody Island. I followed a narrowing course between Goose and Tronson islands; the tall marsh grass lining it drew closer. The channel was only 20′ wide when my concern grew, but there was still clear water in front of me.

I rounded a bend, and the last stretch of water ended in a wall of marsh grass swaying lazily in the breeze. I steered into the nearest bunch of grass to stop the boat, and soon the drag of the reeds held KIMCHI in place. I used an oar to turn the boat around and bring the bow back into the wind. I tried sailing back out of the channel, but after two tacks, I wound up right where I’d started. Sailing out wasn’t going to work. I struck the sail and set the oars in the locks. Rowing, I covered more ground, but if I stopped for an instant the wind pushed the boat askew and back the way I’d come. I had sailed a full mile down this winding, narrowing pathway and decided if there was some other way out, it would surely be better than backtracking. While I stood up and looked around, the wind pushed KIMCHI against the reeds.

The main flow of the river was only 100 yards away but separated by thigh-high grass and who knew what else. Still, crossing seemed better than backtracking. A little to the northwest was a tiny streamlet that extended partway into the marsh. I crossed and rowed in and the boat filled it entirely. Grass rasped on the hull as I rowed, and the oars found purchase more against the roots of the plants than the water. With each pull I plowed through the water lilies that grew in the center of the stream. This worked for 30 yards, until the thickness of the growth brought KIMCHI to a stop. I stood, pulled the oars out of the locks, and poled the boat forward. I used both oars and stood in the middle of the boat, and applied almost as much downward force as I did upward force, as if I were attempting to pole-vault over the bow. This got me through another 30 yards of marsh.

The trail of water lilies marking deeper water ran out. I had followed them as far as I could because they meant easier passage, growing where it was too deep for the grasses, but I had reached the point where all that stood between me and the rest of the Columbia was just that: grass. So once again, I stowed the oars, pulled on my water shoes, and stepped out into the soup.

Cutting a furrow through the grass, the skiff proves itself an amphibious vessel. For the overland trek, all of the gear was just dumped in the boat.

My foot landed on a cluster of grass and the roots supported my weight—I hardly sank in at all. I tiptoed to the bow from root cluster to root cluster, and grabbed the painter. For the last 40 yards, I towed the boat across the grass.

I had at last reached flowing deep water again. I paused to catch my breath. The swath of crushed greenery behind me looked like a giant snake had slithered through the marshland. I walked around to the back of the boat, pushed it forward until only the stern clung to the grass, and with a final shove, launched into the current and dumped myself on my back into the cockpit. I was exhausted and happy to be on my way once more, under sail and drenching summer sun.

Ready to sail again after our unexpected hike, KIMCHI perches on the edge of the channel to the east of Goose and Tronson islands.

I made 20 miles that first day, marshland detour and all. The wind stayed steady through the evening, and I sailed into the Elochoman Slough Marina in Cathlamet, on the Washington side of the Columbia River. My boat was half the size of the next smallest in the marina, and could have been a tender for many of them. I pulled into an empty slip next to a 35-footer and tied off. It was dusk, and the many campers and locals paid me no mind as I made my way to a picnic bench and fired up my camp stove. One bowl of corn chowder and two instant ramens later, I plodded back down the gangway and fell into the boat, where I pulled on my sleeping bag and quickly fell asleep on the foam pads I had tied into the bottom of the boat.

Before my departure from Elochoman Slough Marina on the second morning, I spread my gear out to get organized for the day. I do a lot backpacking and I never slept better in the woods than I do in the foam cushions in the bottom of the boat.

The morning of the second day was much like the first: calm, gray, and cool. Rather than immediately set out rowing, knowing I would likely spend most of the morning fighting the current, I decided to wander into town, so I went off walking. Twenty minutes later, back at the marina, I decided I could wander the town a second time before the wind picked up.

To my dismay the taco joint and brew pub were still closed, even on my second walkabout, so around 9 a.m. I got to rowing again. Within the first hour the sun was out and the wind was up, almost a perfect mirror of the previous day.

Lying supine in the stern is the most relaxing position for me and the most stable for sailing. Removing the rowing thwart and setting it in the bow gives me more room to stretch out. Cloud cover kept the sun off me while I sailed toward the east end of Puget Island after leaving Cathlamet.

Soon the wind had surpassed the first day’s, blowing close to 15 knots astern as I sailed the last leg of the channel between Puget Island and the Washington bank to reenter the main channel.

At the east end of the island, I let the sail luff and looked both ways before crossing the shipping lanes. Two osprey chicks eyed me from their nest atop a daymark.

Where the channels converge the river is almost a mile wide. There were no obstructions and the wind was over 15 knots. Small whitecaps frothed as I sailed among them. My dinghy-racing blood was up, and I angled KIMCHI to run with the swell. Keeping my weight low and aft, I kept my left hand on the mainsheet ready to pull it from its cleat.

KIMCHI started surfing. She slowed in the troughs as I tweaked the rudder in anticipation of the approaching waves, turning the boat a few degrees off the direct path of the crest. As the wave behind me caught up with the boat, lifting its stern, I lunged forward and the boat raced down the face. The rush of water hissed while KIMCHI surged forward. As the wave finally outpaced me and the bow lifted, I glanced over my shoulder and prepared for the next wave.

The sand bar on the east end of Puget Island is almost 40 miles from the mouth of the river but not beyond the reach of the tides. I had pulled KIMCHI 15’ from the water’s edge, but within just five minutes the incoming tide had nearly floated her off.

The day whipped past in a gusty, blue-sky blur. I stopped for lunch at Cooper Island, on a beach so broad that it must have been made of dredge spoil, much the same as Jim Crow Sands.

Around the next bend, I passed the Beaver Generating Plant, a natural gas–powered facility. Beyond a fence that came almost to the river, the thrum of turbines emanated from the stark, metal-clad buildings.

From the power plant I sailed along the slough between Crims Island and the Oregon bank, emerging upriver on the sandy end of the wooded isle. A dragonfly hitched a ride for the length of the slough, sunning itself like a figurehead on the bow. In the main channel next to the island a cargo ship lay at anchor, splitting the river down the middle. The name DARYA SATI, painted in white letters each as tall as my mast, stood stark against the red-and-black hull. In the lee of Crims the wind had calmed, so I bobbed toward the ship with the remaining few knots of breeze pushing KIMCHI. At the ship’s stern, the gap between the hull and the rudder was large enough for me to sail through. I was tempted to try it, but imagining KIMCHI being churned into kindling brought me to my senses.

I left the shadow of the DARYA SATI behind me and sailed along the south shore of a 4-mile-long finger of land pointing downstream from Longview, Washington, passing Willow Grove Park, a stretch of beach backed by a straw-colored lawn and scattered trees. Sunbathers and power boaters were out in full force.

The wind, unhindered, blew through with the steady 15 knots it had sustained all day. I sailed southeast, upriver, to Barlow Point and entered a straight, wide-open corridor between the industrial riverfronts of Longview on the Washington side and Rainier on the Oregon side. It was a noisy, busy gauntlet to run. On either side, timber yards lined the river with towering stacks of Douglas-fir trunks 60’ long. Docked cargo vessels waited to be loaded with the mountains of logs. A tugboat chugged past, the skipper giving me a nod as he steered around a mooring buoy the size of a city bus.

The late afternoon sun shone with a burnt-orange glow, and I knew I needed to find a spot to camp. After passing the tug, I spotted the landmark on the Oregon bank that I had been looking for, a pink stucco building with a terra-cotta-tile veranda roof. It was my friend’s favorite Mexican restaurant in Rainier.

I had made 25 miles that day and had eaten only two energy bars. I beached beneath the restaurant’s patio and hauled KIMCHI above the high-water mark. I climbed up the embankment, sat down at a table, and ordered a steaming burrito. After dinner, I went for a stroll around Rainier’s waterfront before returning to the beach. I slept in the boat, my gear spread across the sand beside it.

I woke on the third day to an easterly wind and clouds looming in the eastern sky, and knew I would spend most of the day getting wet and getting nowhere. I launched in the chill air and immediately started rowing. In about an hour I made it a mile upriver along the Oregon bank, drifted back half a mile crossing the river, and remade the lost ground along the shore just west of Cottonwood Island. I had aimed for the downriver end of the island because of the narrow, slow-moving channel separating it from the Washington mainland, ideal for making progress upriver with as little resistance as possible.

The Cowlitz River flows into the Columbia at the north end of Cottonwood Island. After the morning’s first fit of rain I was not at all dry but I stayed mostly warm by walking KIMCHI through the shallows between the island and the Washington shore.

As I approached the channel, it began to rain, and all of the weekend fishermen anchored along the Washington bank reeled in their lines and motored off. It was the middle of August, our sunniest month, so I had brought no rain gear. I shoved everything I could into the dry bag—map, snacks, water bottles—and piled my foam pads into a vertical stack in the stern so not all of them would get so wet. I put on my life vest for warmth and to keep some of the rain off me. I continued rowing—against the wind, against the current, and pelted by plump summer raindrops. I would have been miserable if it weren’t for the heat generated by rowing. A harbor seal followed me up the channel along Cottonwood. He appeared to be staying drier than I was.

About halfway down the 4-mile channel, the rain abated and I dried off a bit. My pants, which had been soaked through to the skin, slowly turned splotchy with dry patches. I bailed out the water in the boat and then, just as I was exiting the channel to return to the main body of the river, another bank of clouds reared up to the south. They dragged gossamer sheets of rain from their bellies over the hills on the Oregon shore. From afar, the gray veils were beautiful. As they reached the river the hiss of rain on water filled the air, soft at first, then growing as the clouds continued their northward advance. I resigned myself to another drenching.

Tuning out my surroundings, I set to the task of rowing like a yoked ox. It wasn’t until I was a few yards from an industrial loading dock that I looked over my shoulder to see where I was going. With a 90-degree pivot and two quick strokes I shot between its concrete pylons and into the echo under its deck. I spent an hour under there, tied off to a pylon, wringing the rainwater from my clothes and sponging the last drops from the boat with a small piece of foam that had ripped off one of my pads. A pair of ducks swam around KIMCHI. Calm followed the rain, and as it cleared, the whole width of the river shone like a liquid mirror.

In the early afternoon, the sky cleared and the wind lazily drifted back to the northwest. It had yet to build to more than a few knots, but I sailed south in the desultory breeze up the narrow part of the river south of town of Kalama, just before Martin and Goat islands. A stern-wheeler chugged by downriver, carrying a full load of tourists, cameras and binoculars dangling from their necks.

There was no other traffic upriver or down, so I decided it was safe to sail across the channel to the Washington side. It was slow going, but there was just enough wind that I didn’t think I needed to strike the sail and row. I was halfway across the river when I noticed a red buoy about a half mile upriver of me. It puzzled me because this buoy was right up against the Washington side of the river; the far side of the shipping channel was only 150 yards from the Washington shoreline, and I was smack in the middle of it rather than almost across.

Downriver I heard the unmistakable deep rumble of a cargo ship’s engine and the waterfall rush of the bow pushing through the water. I had been bobbing across the river thinking the path was clear, and now this rusted 750’ red-and-gray behemoth had rounded the corner of Sandy Island and was bearing down on me.

The skies had cleared a bit by the time I reached the anchorage in the middle of Martin Island, but an inch of rain had fallen that morning, so I spent the evening drying my gear.

I jibed as fast as I’ve ever jibed, and aimed straight for the Washington bank. The wind was still light and shifty, but I felt confident I had enough breeze and time to get clear. Whoever was at the ship’s helm must have noticed me too, and steered slightly to the west, away from me and toward the channel’s Oregon side. The ship churned passed with just 100′ between us. I looked up at the bridge, and saw, hazy through the bridge windows, someone in a white shirt and black cap looking down at me with a pair of binoculars. I reached up and waved. The crewman’s arm shot up in response, and we held the gesture for a beat as if saluting. The ship continued on its way, and I on mine as I sailed up the slough between Martin Island and the Washington shore. I entered the island’s small cove, a snug anchorage I had spotted on my map earlier that day. There were already five boats anchored there and among them were two floating docks maintained by local yacht clubs. Thick, tall walls of brambles heavy with blackberries lined the shore. I ate my fill before settling in for the evening.

August is the peak of blackberry season and the brambles are scattered all along the river shore. I made many pitstops to pick them, and some were monstrous and I could easily make a meal of the them.

I made my way to the more welcoming of the two docks, the one with the tiki hut strung with lights. I tied off, set up my kitchen, and cooked instant ramen. As evening set, I ate and watched cows grazing along the shore and lights flickering on in the anchored yachts. Despite the lousy start, I had covered close to 15 miles.

The next morning dawned cloudy, but the air was warm and lacked the cool bite that had heralded the easterly storm the day before. There wasn’t any wind, so I started the morning by rowing. As I left the cove, a faint buzzing noise come from the sky, but with no apparent source. The buzzing grew louder, and from behind the trees of the more southerly Goat Island the pink fabric wing of a paraglider appeared. He was taking advantage of the still morning air, and buzzing about with a caged propeller strapped to his back. The buzzing softened as he cut back on the throttle and spiraled slowly down to the meadow on Martin Island. His feet scraped the grass and I thought he would land, but he revved the motor and swooped back into the sky. I continued rowing and followed the slough along the Washington bank of the river.

It was an uneventful morning, apart from a brief tangle when I rowed KIMCHI’s mast into a fisherman’s line that had been cast from a cliff along the bank. With a dead stop and reverse I extricated myself from the monofilament snare. By noon, the wind still hadn’t turned up, so I continued rowing. I rowed the 5 miles from Martin Island to St. Helens and stopped on the shore of Sand Island, a 2/3-mile-long wooded isle across a narrow channel from St. Helens Marina. It’s a well-appointed city park and I was happy to take advantage of the facilities. But while I was using the restroom, some kids wandering around were drawn to my boat. I was walking back to KIMCHI just as they climbed aboard. When they noticed me approaching, they jumped out but I smiled and asked if they’d like to ride in the boat as I towed them through the shallows. They climbed back in, but before I could get the okay from their parents they were called back to the dock; it was time for them to return to the mainland. The kids leaped out once more, leaving KIMCHI with a wealth of sand.

At low tide, this sand bar stretches downriver from Sand Island. St. Helens, visible on the left, is close by. The island looks quiet here, but on this Sunday afternoon it was teeming with hikers and kayakers.

After crossing to the public dock at St. Helens, I consulted my chart. I had covered a lot of ground and was ahead of schedule, so I had some time to kill and took a break to see the town. Things were off to an exciting start when the river current swept a large powerboat against the walkway that bridged the two floating docks. A half dozen boaters appeared as if from thin air, and with much grunting we shoved the 2-ton boat upstream and hauled it into an empty slip. The boat’s crew gathered their wits and made a second launch, this one successful with the application of more throttle.

At the south end of town, on the edge of a vacant concrete-paved lot, I met a chatty local named Howard. Lugging a massive jug, he paused at the foot of a stairway made of railroad ties set into the hillside, then slowly climbed the steps, watering the plants that grew alongside them. Once he got to talking, he forgot about the plants entirely and told me about the old Boise Cascade veneer plant that used to sit on the lot and had shut down in 2008. He recalled in vivid detail the plant in operation, trucks hauling in the debarked logs, machines peeling them layer by layer like so many onions, and barges swinging wide with their loads of veneer around the point of Sauvie Island, just 1/2 mile upriver where the Multnomah Channel meets the Columbia. The site didn’t look like much now, just a bare fenced-in lot with a rusted dock.

I had my eye on the Multnomah Channel, the narrow, winding 22-mile-long distributary from the Willamette River. The wind had filled in while I was ashore, and so in the late afternoon I set sail from St. Helens and said farewell to the Columbia and entered the 200-yard wide mouth of the channel. A mile in, Scappoose Bay split off from the Multnomah, and I slid along its bifurcated entry, with the dwindling northwesterly nudging KIMCHI along.

When I arrived at the bay’s only marina, 1-1/2 miles in, it was nearly dusk and there was no place to dock, so I rowed farther into the bay. It quickly shallowed, and in about 1′ of water I stopped, pulled my oars from the locks and plunged them blade-first into the mud. With the oars serving as stakes, KIMCHI, snugly tied to the looms, was prevented from swinging in the wind.

After dinner, I settled in for the night. In the dark, I checked the knots around the oars one more time, and laid back in the boat. The light evening breeze flowed over the top of the gunwales, carrying the smells of mud and grass. It was cool, but in my sleeping bag I was comfortable, and soon fell asleep. It had been another day, and another 12 miles.

When I woke on the morning of my last day, I was glad to find KIMCHI had not pulled free from the mud and drifted into the weeds. I backtracked out of Scappoose and rowed into the Multnomah Channel. Judging by the weather, the Columbia likely had plenty of wind. The channel, on the other hand, only received the irregular dregs of the wind, tumbled over obstructions along its narrow and winding path. I made my way in fits of rowing and sailing, and eventually got tired of setting and striking the rig every 30 minutes. I decided that unless the wind rose above 5 knots, I was going to row.

Multnomah Channel felt like a small town’s main street, compared to the highway of the Columbia. The southern half is lined with houseboats and the residents lounged on their porch decks, waving as I passed. A leather-skinned woman in a red bikini riding in an outboard-powered rubber dinghy passed me twice, as if she was out on a trip to the grocery store for milk.

By midafternoon, the wind had withered in the August heat. I took my shirt off to stay cool while rowing, but the air was sticky with heat and humidity. By the time I passed under the Sauvie Island Bridge, I was practically in Portland. The wind picked up above my 5-knot threshold, so I set the sail and donned my shirt.

The St. John’s Bridge, the first on the approach to Portland, was bathed in the afternoon light as I sailed up the Willamette River. It was a downwind run, so I pulled the leeboard up and set it in the boat just forward of my feet.

Just 1-1/2 miles beyond bridge I reached the Willamette, my home river, and the last leg of my journey. I passed under the St. Johns Bridge, the first of 12 that I’d pass under sailing through Portland, and stopped on the left bank at Willamette Cove. A sign on the shore said the site was toxic with industrial waste once dumped there. The woman walking her dog, the man with the camera, and the teenagers ambling across the sand didn’t seem to mind this, but I decided against spending the night there. It was nearly sunset and I still had more than 5 miles to travel up the river.

I took my last rest stop of the voyage at Willamette Cove. The sun was setting and the western bank of the river was already in shadow. I had just a 9 more miles to the voyage’s end at the Willamette Sailing Club.

With my running lights on, I set out from the cove. I was worried about sailing through the industrial part of Portland, which lay ahead, but I didn’t see another boat on the water. It was not until darkness had fallen completely, that I saw anyone else.

The city lights sprang up around me as I left the rougher part of Portland’s riverside behind me and sailed through the downtown district. Pedestrians crossing the Hawthorne Bridge stopped and waved as I passed beneath them. WILLAMETTE STAR, a 100′ dinner-cruise ship, swung wide around me and starburst flashes from the diner’s cameras sparkled beneath the steady glow from the city.

It was nearly 10 p.m. when I reached the Tilikum Crossing Bridge. The reflections of its lights glowed orange and undulated on the slow-moving water. The best wind of the day filled in from the north, bringing KIMCHI alive. I left the city lights behind and sped down the inky waters of the southwest waterfront. At 10:10 p.m., in the pitch dark, I slid into the docks at the Willamette Sailing Club. The day’s 25 miles brought me to the end of a nearly 100-mile voyage. I derigged KIMCHI and stowed her under buzzing fluorescent lights.![]()

Torin Lee lives in Portland, Oregon, and wears a few hats at a local solar installation company. On summer weekends he teaches at the Willamette Sailing Club. He learned to sail in college, racing Flying Junior dinghies. He still enjoys racing with the club fleets, and got the boatbuilding bug from the folks at Portland’s RiversWest Small Craft Center.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Very nice story, Torin. I have often thought of sailing in that Lower Columbia region. Thanks for posting this. Nice photos, and nice boat.

Thanks for the story, Torin. Proves that you don’t need a big fancy boat or need to go far afield to find adventure.

Torin, great small-boat sailing adventure story. Thanks for sharing. How did you prepare for overnighting in potential rainy conditions in your open skiff? Also, can you fully stretch out when sleeping in this design? I love the removable rowing thwart—good intelligent design.

Best,

Brent

Great read, thanks for the adventure. Much more visceral experience than in a SanJuan 28. Have you read Swallows and Amazons?