Some years back I was rowing in a race with my good friend Bill Gribbel in his tandem wherry, DONOGHUE. She was a copy of a circa-1870 pulling boat found, restored, and documented by the late Westport, Massachusetts, boatbuilder and designer Bob Baker. The wind was up and for 4 miles we pulled into it, catching a bit of spray, and then it was around an island and down the home stretch. It should have made for a quick and exciting downwind run, but that’s when the fun stopped. With the stiff breeze on our quarter, we spent a lot of time pulling on one side to keep DONOGHUE on the right heading. Our trim was a bit bow-down, so the boat was constantly trying to turn upwind.

Weathercocking is the tendency of rowing and paddling craft to veer up wind in a crosswind. The leeward bow is subject to increased pressure as the boat moves forward and the wind blows it downwind. The stern meets lower pressure, a result of the turbulence created by the boat’s passage through the water. The stern drifts downwind through this turbulent area faster than the bow does through undisturbed water, so the boat angles into the wind. Rowing or paddling harder only makes the problem worse.

Many sea kayaks are equipped with a retractable skeg or a rudder that, when deployed, can mitigate the downwind drift of the stern and eliminate weathercocking. A boat without a retractable skeg or rudder can be loaded stern-heavy; the increased draft reaches below the turbulence to diminish the downwind drift. And, as the stern sinks, the bow rises, which lessens the water’s grip on the forefoot and increases the area acted upon by the wind. The result is a balanced downwind drift, without the bow turning into the wind.

Ben Fuller

Ben FullerWithout ballast, the dory TIPSY sits right on her lines, with her boot top parallel to the water’s surface (top). With ballast in the stern, the bow rises, exposing more bottom paint, and the stern sinks, submerging the boot top (bottom). The change in trim will improve the dory’s tracking and downwind performance.

A well-designed kayak or rowboat normally has a slight stern-down trim to better hold a straight course. As Bill and I discovered aboard the DONOGHUE, that trim may not be sufficient to get the boat to maintain a steady course in a crossing wind. Adjusting the trim to remedy weathercocking can be achieved by taking along some movable ballast.

SBM

SBMThis double-ended gunning dory, like the author’s Swampscott dory, has no skeg, so dory stones can settle the stern deeper in the water and improve tracking in a following sea. The three stones here together weigh about 60 pounds.

Fishermen in Maine would carry dory stones—head-sized beach rocks—and use them to change the trim of their boats. Their boats were usually light in the stern, so the stones would be set well aft. If Bill and I had carried some dory stones aboard DONOGHUE, we would have trimmed the boat by the stern and she’d have run easily. They would not have affected the upwind performance.

My Swampscott dory TIPSY can be a challenge to row in calm and windy conditions. Like most dories she’ll spin in her own length when light and rowed solo. Her stern sits just a few inches into the water and, unlike a flat-bottomed skiff or a round-bottomed rowboat, she doesn’t have a skeg. It makes her very maneuverable at the expense of good tracking. A few dory stones, found in any Maine cove, do the job of helping her track better in a calm and in wind.

SBM

SBMA small bag, loaded with bird-shot or sand, can fit well aft in the tight spaces of a double-ender.

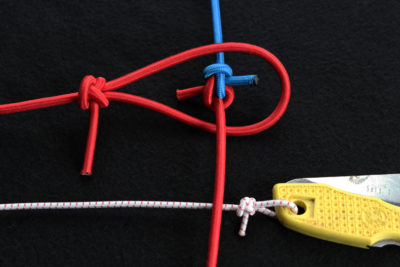

My Dias-designed Harrier, RANTAN, has the same problem as DONOGHUE. As built, with two of us at the oars, she is a bit down by the bow and in a crosswind will inevitably be “griping,” tending to turn into the wind and difficult to keep on course in a calm. Because RANTAN is a double-ender, space is too tight at the stern for large rocks, so I had to find a small, very heavy bag that would fit well aft, on top of the mizzenmast step.

I remembered that old-time sailing canoeists often carried bags of shotgun shot, so I bought two 25-lb bags of #7 birdshot, the modern, lead-free kind. A couple of canvas bank coin bags fit the plastic shot bags nicely, protecting them and giving me something easier to grip. RANTAN is now much better-behaved when I go rowing with a friend.

The trim ballast is also a bonus when I’m sailing RANTAN. I can set it to windward on a long tack or set on the thwart near the leeward rail on a light day when I don’t want to sit cramped up in the middle of the boat.

Ben Fuller

Ben FullerFive gallons of water provide 40 lbs of ballast in the stern of the author’s Swampscott dory.

I’ve more recently gone to water ballast. There is plenty of room in TIPSY’s stern for a 5-gallon water bag weighing just over 40 lbs, and the bag doesn’t ding up the dory’s interior. I could fill it with seawater at the start of any outing or carry it empty until I need ballast, but I like to have some drinking water aboard. Since the dory spends the boating season afloat on a haulout I just fill a bag with tap water, leave it amidships when she is swinging on the haul out, and shift it aft as needed.

I usually row solo from the center thwart, and put the water bag in the stern for downwind rowing. But, if I am heading downwind in a real breeze, I’ll need more weight aft than the bag will provide, so I will pull from the aft oarlocks, and have the bag far enough forward to balance my weight a bit and keep the bow from rising too high. A bit of bilgewater lets me see the boat’s trim; it will stay amidships when things are balanced and run aft when I have the stern-down trim I need.

Few things are as frustrating in a rowboat as difficulty in keeping it headed where you want it to go. Pulling hard on one oar to fight weathercocking to keep a poor-tracking boat on course can ruin a nice outing. A bit of ballast will trim the boat out nicely.![]()

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, has been messing about in small boats for a very long time. He is owned by a dozen or more boats ranging from an International Canoe to a faering.

You can share your tricks of the trade with other Small Boats Monthly readers by sending us an email.

Another advantage of water ballast is that, in case of a swamping, it provides neutral buoyancy. With stones, sand, or shot, there is the possibility of sinking. Water ballast won’t sink your boat, provided you have some sort of positive buoyancy such as floaty hull material, air chambers, or foam blocks.

My wife calls me “movable ballast.” Thanks for the info.

We use the Herreshoff rowboat for commuting to and from Dangar Island, Sydney, Australia. The original design has no skeg or fin. It was OK rowing but when coasting the boat would yaw annoyingly. Consequently I now always fit a sturdy stainless-steel fin and the boat tracks nicely but is still able to maneuver nicely. The draft is now about 6″, not too bad for most rowing. Of course if the bow is trimmed down it tracks poorly and if it is trimmed down at the stern it does not row as easily.

Another solution afforded in my Whitehall is its two rowing stations. The primary thwart (slightly aft of center) is good for most conditions up or downwind until the breeze freshens up to about 8 knots. If I need to row upwind at that point, I’ll shift to the forward thwart to raise the stern–which allows it to track easily directly upwind. The bottom line: I plan my daily hour-or-so outing around the predicted wind direction, always start off rowing upwind in the forward thwart, then shift to the primary thwart for returning home with the wind. I avoid as much as possible rowing cross wind when alone in the boat.

Thanks, Ben Fuller. Your article may help me in one of my kayaks that lacks a retractable skeg. I will experiment with loading the stern more.

My lead shot ballast bags were old coin bags that I got from my mother in law, a cashier. After a bunch of years they needed replacement, rot was the culprit. So I went on line and found some new nice simple canvas bags and can retire the coin bags. I’ll probably pick up some more shot as they came in packs of three. As compact as they are they’ve fit under floorboards of many traditional sailboats.

I use sandbags designed for anchoring soccer goals (easily found on Amazon). The good bags have handles, are lined (so they don’t “leak” sand), and the zippers can be zip tied. I carry six in my Devlin sailing dory (18′). They carry 45 pounds each and the handles make them easy to move around when I’m underway. If I’m sailing with another person, or the wind is light, I’ll take one or two out and leave them in the truck. The bags are sturdy (heavy duty polyester) and the thing I like about sand bags is that I can walk on them, so there is no tripping or stepping over them if I need to move forward to a rowing station or to the mast to brail the main sail.