After having built and used kayaks steadily for 21 years, I had begun to think about a different type of vessel to use for cruising and camping on local and familiar waterways close to my home in Portland, Oregon. I had done numerous overnighters with my kayaks, and had always camped on shore. Sandy beaches, a wealth of uninhabited islands, and abundant access to land made camping easy, but a vessel to sleep in seemed like a further step toward ease, and the idea of sleeping on the water had an irresistible appeal.

After deciding to build a “floating campsite,” I had to find a suitable design—a stable, small, platform that would be very simple to build. It had to be a historic design, something a little off the beaten path, with a workboat background. Years of studying old Arctic kayaks had molded my sensibilities and taste.

I came upon the garvey box while flipping through Howard Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft. It was built near Tuckerton, a small town on the south end of New Jersey’s Barnegat Bay. The garvey box served the same purpose as the better-known sneakboxes of the area, but was easier to build. I started building in January, and launched in mid-March 2014.

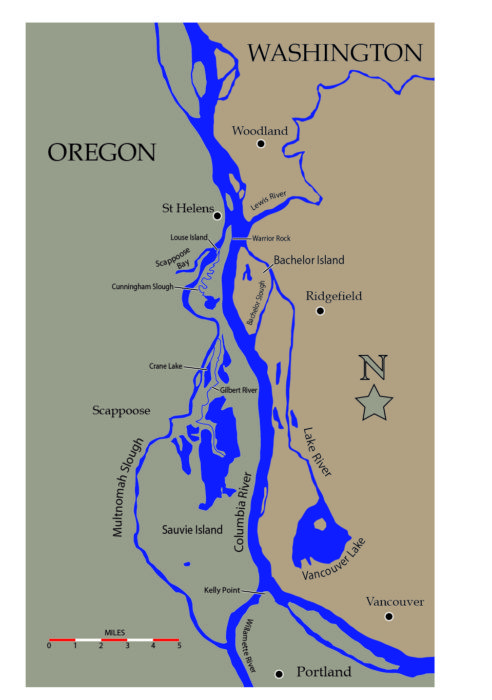

I had very little experience sailing or even rowing, but I worked out the kinks and learned the ropes, and began to plan an overnight for ZEPHYR’s third voyage. I would launch at the south end of Vancouver Lake and make my way to Lake River, which drains into the Columbia 11 miles farther north. I expected this would give me one night on Lake River, and plenty of options to progress the next day.

All photographs by the author

All photographs by the authorLoaded and ready to go, ZEPHYR awaits her oarsman at the south end of Vancouver Lake. The island, 1-1/3 miles away, is barely visible through the fog to the left.

On April 7, I set out in fog so thick that I could barely see the island in the middle of the lake. I started out under oars, but when I reached the island, the fog had broken, and a touch of a favorable south wind picked up. I unbrailed the spritsail and made a meandering run to some inundated willows at the north end of the lake, and stopped for lunch in bright sunlight.

The wind failed as I entered Lake River, so I brailed the rig and went on under oars. Lake River is a pretty stream lined with trees and pastures. It is about 250′ wide, and its western shore is mostly floodplains and pasture, some lined with ash and cottonwood, some bordered by flood dikes. Gentle bluffs to the east are wooded with oak, ash, and fir, and hide the populated rolling plains of Vancouver above. Beneath the bluffs a heavily trafficked rail line lies within a half mile from the river, and in some places the tracks are just 75′ away.

A shady cul-de-sac off of Lake River provided an ideal resting spot. Lake River is plenty sleepy, but this cove oozed silent primeval slumber.

Toward midafternoon I ducked into a hidden harbor on the western shore. It meandered a little ways through a dense wood of ash and cottonwood that created a shade-giving canopy over the water. I had a snack and rested a bit; the only noise was the distant honking of geese, and two raccoon kits chasing each other up and down trees. It would have been an ideal anchorage for the night, but it was too early in the day to stop.

A very pleasant and peaceful moment on Lake River, with just enough wind to move me along, and slow enough to allow my mind to wander.

I nosed ZEPHYR back out into Lake River; the south wind picked up again and teased me along at a dreamy pace. I was nearly asleep at the helm when a huge and cacophonous flock of Canada geese suddenly took off from a field just astern of me, clearly startled by something. They rose into the sky, and the surface of the river below them erupted as if hit by a downpour of oversized hail. I was quite pleased to be out of range of their bombs.

Not 15 minutes later, the pastoral waters erupted again. A bull California sea lion gave a poor carp a violent thrashing just 30 feet off my port bow. The sea lion slapped the pallid carcass back and forth, bent on eviscerating it; I was lucky not to get splattered.

Her anchor set in fine mud, ZEPHYR is readied for her first night out. The freight train in the background up on the berm did not bode well for a good night’s rest.

When the sun was getting low, I sought a haven for the night. A few creeks drained down the slopes of the steep eastern shore into Lake River. The first creek I came upon had a lovely ash-canopied cove, but it was quite close to the railway. I could see on my charts that another cove farther downstream might be more promising. I rowed another few minutes and turned into the meandering creek, and came to a stop some 20′ in, just as the sprit snagged a low branch.

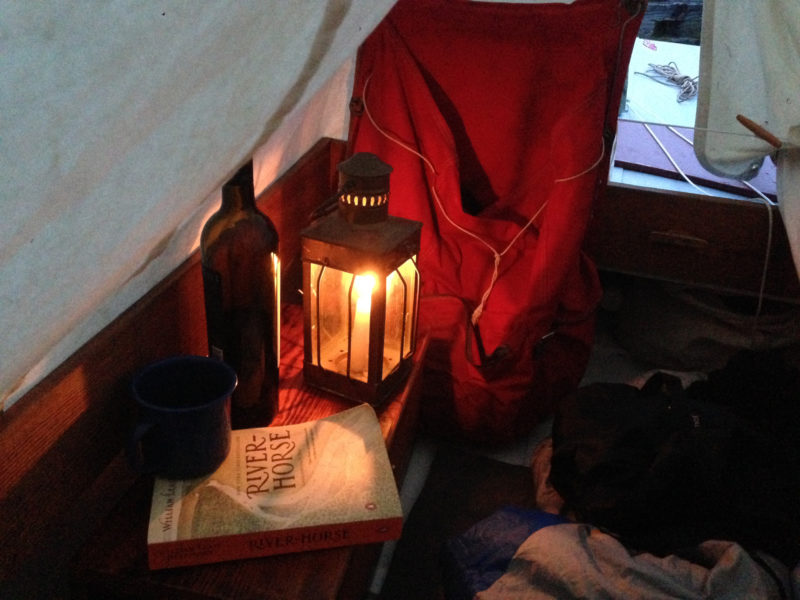

I brailed the sail and unstepped the rig, chucked my 10-lb Navy anchor overboard, and let out the chain and some 10′ of rope. (I’d found the anchor in the Columbia River 15 years ago while kayaking, and knew someday I’d have a boat for it.) I stepped a short dummy mast forward, secured a stick at the aft end of the cockpit, and then draped the simple canvas pup tent I’d made over the uprights. Toggles accessible from inside and out of the cockpit secured the tent around the coaming. My rowing “thwart,” a simple box full of tools and camping gear, went to the port side—reoriented fore-and-aft—to serve as my dining table and lantern stand.

With the rowing seat serving as a nightstand I was ready to turn in for the night.

I had brought cans of soup, a few baguettes, and some tins of sardines, but I was too tired to fire up my alcohol stove, so I had the soup cold—right out of the can. I uncorked a bottle of red wine, poured to the rim of my enamel coffee mug, and reached for my book, William Least Heat-Moon’s River Horse: Across America by Boat. The light was good and bright in my raw-canvas tent, even for dusk reading, but soon I lit the candle lantern, if only for ambience. Before I knew it, the sun had set, so I dragged my sleeping bag out from under the foredeck and laid it out, foot forward. I took one last peek out the back of the tent at the yellow and orange twilight mirrored on Lake River and framed by the leafless ash branches of my snug harbor. As the sky faded I fell asleep, using my life jacket as a pillow. The last sounds I heard before nodding off were distant geese and the faint lapping of ripples caused by fish jumping or beavers swimming nearby.

My quiet bliss didn’t last too long, as I soon found that being 100 yards away from the railroad tracks isn’t much more quiet than being 100′ from them. How irrational the startled nighttime mind can be, thinking the train is bearing right down on one’s very anchorage! This terror must have happened at least five times throughout the night.

I woke around 8 a.m. to bright daylight, and had a leisurely breakfast in bed while reading more River-Horse. I soon turned attention to my own adventure, so I set to converting ZEPHYR from a bedroom back into a vessel. Called to shore by nature, I realized that I hadn’t set foot on land since 10 a.m. the previous day: I had spent 23 hours within ZEPHYR’s 33″ x 72″ cockpit and had never felt the least bit confined. All comforts I required were close at hand, and the gently rockered floor, unencumbered by fixed thwarts or clunky framing, was exactly the camping platform I had hoped for. The only thing it required was for me to place it in the loveliest settings I could find!

With water glassy and the rig brailed, I rowed up Lake River, passing an abandoned half-sunk vessel.

When I emerged from my harbor, the river was still and smooth as glass. There was no wind, so a-rowing I went. At Ridgefield, 8 miles downstream from Vancouver Lake, I assessed my situation. There was little promise of wind. A mile north of Ridgefield I could turn south on the Bachelor Island Slough and enter the Columbia across from Sauvie Island with the choice of heading north or south as wind and current might favor. Or I could continue north another 2 ½ miles on Lake River and enter the Columbia on the north end of Bachelor Island, across from Warrior Rock lighthouse near Sauvie Island’s northernmost point.

The speck of white on the distant shore is Warrior Rock Lighthouse on Sauvie Island. To get there I’d soon be rowing across the Columbia River.

I chose to strike out for Warrior Rock. The Columbia was glass-smooth. The current was running, but presented no challenge to reaching the lighthouse under oars, as it was slightly downriver. I came ashore on a sandy beach in a nice, protected cove just north of the lighthouse.

Warrior Rock Lighthouse stands just across a horseshoe cove from the beach where I landed ZEPHYR. The basalt dike below the light house made a perfect picnic spot.

The 28′-tall lighthouse was built in 1930. The upper half is an elegant octagonal shape, while the lower half is an elongated concrete hexagon, shaped and oriented to cut the water like a ship when the Columbia floods. It sits prominently on Warrior Rock, a former site of native canoe burials. I sat down at the base of the lighthouse and downed a can of soup and a crust of bread. A west wind alighted on the river beyond the lee of Sauvie Island’s tree-lined shore. Eager to take advantage of it, I returned to ZEPHYR and rowed her off the beach. With the westerly, I could reach up the Columbia toward Portland or a half-mile downriver, around the northern end of Sauvie Island, into Multnomah Channel at the town of St. Helens. I chose to sail north.

At the tip of Sauvie Island, I tacked and close-reached south, up Multnomah Channel, dodging old pilings and lines from the many fishermen in aluminum skiffs anchored in the channel. The west wind held up nicely, and I made good progress upriver. I passed the entrance to Scappoose Bay, which breaks away from the channel towards the west about 1¼ miles from the Columbia. This bay is about 2 miles long, though it continues on in several secluded meandering creeks that I’ve yet to explore. A night in the bay somewhere was a fine possibility, though it was too early to stop.

As I approached Louse Island, tucked into the long neck of Sauvie Island, just across from Scappoose Bay, I decided to head for a favorite stream hidden behind Louse Island: Cunningham Slough. Meandering some 4 miles into Sauvie, the slough measures only 2.1 miles straight-line from its mouth to Cunningham Lake. A night in this narrow mud-banked and ash-lined slough would be truly peaceful. I’d never been all the way up to the lake at its end.

ZEPHYR’s shallow draft allowed her to explore water too thin for most boats.

The water was high, making it an opportune time to travel the full length of the slough, but about a mile up I grew tired of rowing: The wind in the 90′-wide slough was nonexistent. I dropped anchor to rest, read, and if need be, nap. Later that afternoon, I woke up groggy yet anxious about deciding where to proceed next. Up-slough would have been easy and comfortable, and, practically speaking, resulted in at least two more nights out. I was prepared for such a commitment, but at the time making “progress”—under sail, if possible—weighed more heavily, and I rowed back toward Multnomah Channel.

Clouds had washed over the blue sky, and the west wind had picked up considerably. When I reached the channel, I stowed the oars and unbrailed the spritsail, and made a reach to the south. The wind curled around and over the tall cottonwoods on the weather shore, and I endured severe blows from astern. My boom leapt and galloped several times in the chaotic gusts. At times the winds felt very favorable to forward progress, and yet I was frequently backwinded to a stop. Sailing up a narrow channel with a tree-lined shore is fraught with surprise and disappointment.

I passed the last of the trees along the weather shore and came to an area that gave way to low meadows. The sailing should have been steadier here, but instead the wind died completely. Taking to the oars, I found that the ebb had strengthened, and my work began in earnest. Along this stretch of Multnomah Channel, one shore is lined with rip-rap, and the other was sheer banks of mud tangled with logjams: there weren’t any inlets for refuge for at least 2 ½ more miles. A south wind sprang up, giving me more to work against, and I could see that black sodden clouds over Portland were headed my way. I could’ve easily backed out under sail to Scappoose Bay or Cunningham Slough for the night, but the urge to go forward persisted, and I raced against the threat of a heavy rain to the mouth of the Gilbert River.

I pulled hard to get ZEPHYR into shelter, weighing every other minute whether or not I should sacrifice some ground made by taking time to don a raincoat. Every inch seemed to matter, so I kept on in shirtsleeves. My goal for the evening’s anchorage was a floating moorage dock just at the mouth of the Gilbert River.

With parts of me chilled, and others hot with exertion, I reached the mouth of the Gilbert River and made my painter fast to the dock. ZEPHYR streamed down-current and downwind from the end of the platform. The very moment I had the tent out and half set up, the clouds let loose. There is something dismal about tenting in the rain, but this time it felt like a narrowly won victory. My tent, made of untreated canvas, was untested in any rain, let alone a downpour, but it performed superbly. The cotton fibers swelled and blocked the hammering rain and took each heavy drop with a low solid pat instead of the urgent high-pitched pit-pit-pit that dainty synthetics make.

I slipped into my sleeping bag and ate a quick meal of cold soup. The pat-pat-pat lulled me to sleep quickly. It wasn’t to be a night of good sleep, however. First, either the wind reversed or the tide turned (or perhaps both), and ZEPHYR bumped against the dock. After this gentle yet awakening jolt, I realized my sleeping bag was soaked. Damn the canvas! I scrambled out into the dark with a flashlight and perched on the wet foredeck, undid the painter, and sculled over to a snag I’d seen earlier. After tying up to it, I climbed back into the cockpit and I noticed that my water bag had come open—all the water in the boat had come from this, and not the rain. Relieved that I hadn’t used the wrong material for the tent, I slept the rest of the night in quiet, damp victory.

The next morning brought dry and sunny weather, and several options to choose from: up-channel and up the Willamette 27 miles to Willamette Park in Portland; up the Gilbert River 4 miles into the heart of Sauvie Island; up Crane Slough to Crane Lake; or back down channel to Scappoose Bay, the Lewis River, or either north or south on the Columbia. I chose none of these, and instead decided to call it quits.

Writing now in the middle of winter, I should have kept going. I could have gone to Portland, met my family for lunch, and then headed back down the Willamette River to Kelly Point, where it meets the Columbia. From there, the course might be east for Cascade Locks or The Dalles, or perhaps north and west, which would carry me down the Columbia toward the ocean, perhaps to Astoria. But this was nothing grand—just a two-night test run. I hauled out at the Gilbert River boat ramp and called home. My wife soon arrived, and I hoisted ZEPHYR on the top of the car.

The last 48 hours had been magical, and I marveled that I had only spent about 15 minutes of it with my feet on terra firma. I came away with a list of things to add to the boat and to my gear, and a hunger for more voyages.![]()

Harvey Golden has built scores of replicas of traditional Arctic kayaks. He is the author of The Kayaks of Greenland: The History and Development of the Greenlandic Hunting Kayak, 1600-2000 and recently opened The Lincoln Street Kayak and Canoe Museum in his hometown of Portland, OR. The museum houses over 50 of his kayak replicas.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your travels in a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Harvey’s 21 years wedged into boats that fit like a shoe on a foot make him especially able to appreciate this tiny yacht. Thanks for the inspiring article!

This is a great read, Harvey. Thanks for all that you do to preserve, restore and re-create historic craft, and prove their continuing utility.

Harvey, thanks for taking us along. It was fun. I am planning a fall trip leaving from just below the Bonneville Dam. Now I can see that just passing through your area isn’t good enough. You have added several more days to my trip!

Great story, Harvey. I wish we had big rivers down here in central Victoria, Australia.

Thank you all for the kind comments!

What a nice little cruise! Thanks for sharing. Is that a cotton sail? with hemp lines?

Thank you. The sail is cotton canvas (7 oz., if I recall correctly—same as the tent). The running rigging is parachute cord (I’m embarrassed to say), the snotter and the sail roping are manila, and the sail is laced to the mast and bent to the boom with coir (coconut husk rope). I suppose I was cleaning out a bucket of loose ends when I rigged her.

Nice-looking little vessel. Where does one finds coconut husk rope?

I got the coconut husk rope at a bamboo/garden supply store in Portland. I think it’s made in Japan. If you google “coir,” you should be able to find local sources. It isn’t the strongest stuff, but works for a small craft’s sail lacing nicely, although most folks might think it isn’t too pretty.