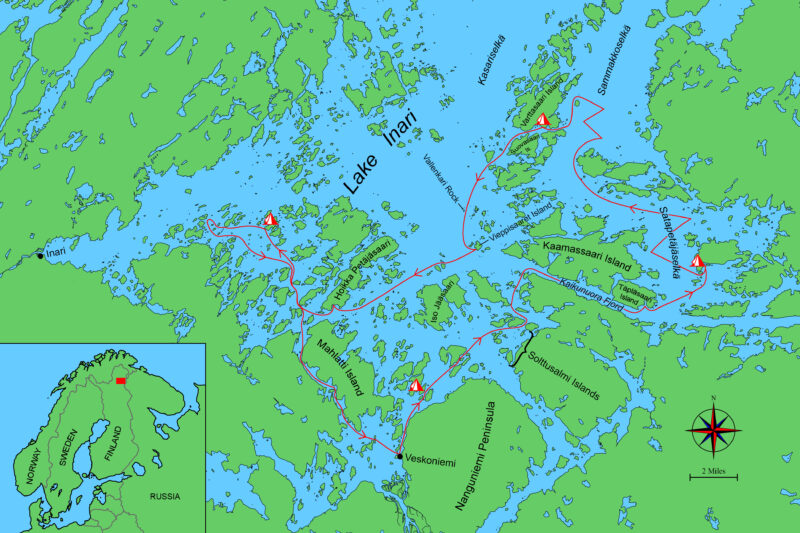

After more than 12 hours’ driving, plus an overnight camping stop on route, my daughter and I finally arrived at the small remote harbor of Veskoniemi on the southern shore of Lake Inari—our cruising ground for the next four days. Lake Inari is the third largest lake in Finland and lies above the Arctic Circle in Northern Lapland. Its 420 square miles stretch from the village of Inari in the west to the Russian border in the east, and to the Vätskär wilderness reserve 43 miles northeast of Veskoniemi. The lake is dotted with more than 3,000 islands and has several wide-open stretches of water that can be hazardous for small vessels in strong winds.

I had visited the lake by myself once before, when my daughter and namesake of the lake, Inari, was three years old. I had vowed to return with a suitable sailboat and to bring Inari with me so she could experience for herself the beauty, size, and untamed wilderness of the lake. The water is clear and drinkable with a healthy fish stock; the islands and shores are austere and unspoiled.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorWe set sail from Veskoniemi in the late afternoon after a 12-hour drive. It was the perfect weather for our departure, and even though it was already after 5 p.m. there would be about six more hours of sunlight.

We loaded our Ness Yawl NESSIE with camping gear, water, and food and readied her for sailing. We were 140 miles north of the Arctic Circle, but it was the end of July, so we had missed the midnight sun. Nevertheless, the days were still long, the sun setting at about 11:30 p.m. and rising again at 3 a.m. By the time we were ready to embark, it was late afternoon, and we were excited to swap the car for the boat.

The forecast was not ideal—we were headed north into an expected northerly wind—but that first evening there was still a gentle southerly breeze, perfect for our first forays into Lapland’s great wilderness sea. The harbor of Veskoniemi was quiet with only a few people around as we hoisted the balance-lug mainsail and small leg-of-mutton mizzen.

NESSIE quickly picked up speed to sail downwind through the narrow channel between the Nanguniemi peninsula and the offshore pine-forested islands. The warm rays of the evening sun danced on the water, and on the horizon the distant hills stood dark against a light-blue sky dotted with chalk-white clouds.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

A couple of miles from the harbor we passed an island no bigger than perhaps two acres. It was covered with pine trees and low wild bilberry, crowberry, and rosemary bushes. The forests on the lake’s small islands are not dense, and the lower limbs of the trees have typically fallen, so walking through them is easy.

Because of the openness of the vegetation, the woods offer little barrier to the wind and, with a fairly constant breeze, at this time of year there is little trouble from mosquitoes. By contrast, the middle of summer brings swarms of mosquitoes and gnats. On the western side of the island, we spotted a cove no more than 40’ wide and decided to call it a day. There were hidden rocks in the shallow water, so we lowered the sails, raised the rudder and centerboard, and poled with an oar into shore.

We tucked NESSIE tightly into a small bed of reeds at the deepest end of the cove, happy that there was no need for the anchor. We were not the first to have made use of this natural harbor—someone before us had left an old pallet to serve as a pier, and a log stuck into the rocky bottom near the shoreline to be used as a mooring bollard. It was 6 p.m. and, with the sun still high in the sky, we had plenty of light and time to set up our camp.

We hadn’t sailed far since launching, but when we spotted a sheltered little cove with a flat area for our campsite, we called it a day. The evening was calm, the air still warm, and we were surrounded by the gentle sounds of island life—the lapping water, the gentle breeze in the trees. We tucked NESSIE’s bow into a soft bed of reeds and set up our camp.

We tossed our camping gear ashore and prepared for dinner. Sitting on the dense cushion of bushes and moss I lit the alcohol stove, and we cooked up pasta with fresh avocado sauce, spiced with chili, garlic, and lime. Inari gathered some cloudberries for dessert. We were still only a couple of miles from Veskoniemi, and as we sat and ate, we saw a few sport fishermen and even a tandem canoe pass by, returning from the lake. As the sun got lower, the wind fell, the cool air enveloped us, and we fell asleep in the stillness of the northern night.

When I woke around 8 a.m. I could hear small waves slapping against NESSIE’s lapstrake hull. The wind had turned north and was building. Inari returned from a morning stroll and told me that at 5 a.m. it had been dead calm. Together we walked across the island through the sparse forest, stumbling over the low-growing bushes. As we reached the east side of the island the dense scent of wild rosemary gave way to the freshness of water over loose shingle, and we emerged from the trees to discover a secluded beach with silken sand. We both took a dip in the arctic water, which was slightly warmed by the recent heatwave but still chilly.

The wind built steadily through our first morning. The forecast predicted a 17- to 20-knot breeze, so we set sail with a single reef and no mizzen. We were headed north, away from Veskoniemi, and the lake seemed devoid of human life.

Refreshed, we returned to our camp for breakfast, packed up the boat, and checked the weather forecast on the Norwegian Meteorological Institute service, Yr.no, which covers all of Scandinavia and beyond. For this trip we could select both the village of Inari and Inari lake, which gave us an accurate on-water forecast. That day, Yr.no was predicting 17- to 20-knot winds. Time to bend-in one reef and unstep the mizzenmast.

We set sail in the overcast morning and headed north to tack through a maze of low islands, some a half-mile long, others barely 200 yards end to end. Between the islands, the channels were narrow, averaging no more than 300′ across, and the wind was gusty, its direction shifting. Sometimes it blew up and over the islands, sometimes it veered around the headlands to funnel down the narrow fetches. I had only previously sailed NESSIE solo and lightly loaded. Now, with the weight of camping gear, food, water, and a second person, she had improved stability, and better tracking and tacking performance; I was pleased.

Each day we stopped for breaks and lunch. We supplemented the ingredients we had brought with foraged foods such as cloudberries and brittlegill mushrooms from the island forests.

We took turns navigating and steering. It had been a couple of years since we had cruised together, but from an early age Inari has always been a trustworthy helmswoman; now turned 19 she had also gained confidence in navigating.

After tacking our way up the narrow, but marked, channel through the Solttusalmi islands we turned southeast into the Kaikunuora fjord.

There are several fjords between the larger islands on Lake Inari, and they can often drastically affect the wind direction. Today we were lucky; the wind held from the north-northeast, and we sailed down Kaikunuora on a fast beam reach. It was a welcome break. Clouds gave way to the sun, its rays warming us as we sailed along the fjord, its shoreline strewn with large boulders beneath steeply rising slopes topped with dense pine forest. The fjord is barely a half-mile wide, and its 5-mile length seemed endless, but eventually we reached the eastern end and stopped for a break on a small headland on Täpläsaari island.

On our second night there was no soft reed bed to pull into, so instead, we tied NESSIE’s painter to a tree and put out a stern anchor to keep her from swinging around onto the rocks.

Sailing through the morning we had amused each other by reading aloud the names of islands, fjords, and peninsulas marked on the chart in both Finnish and Sámi, the language of the indigenous people of the Scandinavian north and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. Some of the place names were unlike anything we had heard before. Some creatively described the appearance of an island, others clearly referenced a meaningful event in someone’s life such as Lost Pulley Island, and Oar Bending Island.

Leaving the fjord and heading northeast across the stretch of open water known as Satapetäjäselkä (in Finnish selkä means open water), our progress to windward was slow. We were sailing directly into a short, sharp chop that was building against us. We began looking for a suitable campsite. Here the waters around the islands are shallow, but with our centerboard and rudder raised, we could coast into just about anything.

We landed on a low and narrow island little more than 100 yards long or wide. It was covered with low-growth berry bushes, and we pulled in beside a living but crooked old pine tree that stretched out horizontally over the water. The island’s vegetation was sparse—widely spaced crooked pines over the low-growing berry bushes—and there was no natural windbreak. But, along the shoreline a soft, low-rolling bush-and-moss bed gave just enough shelter for our tents and to light a fire near the water.

Before eating, we explored our surroundings. The trees were all small. Among the more common, though markedly misshapen, pine trees were the more unusual dwarf birch, rarely exceeding 7′ in height. The living trees were interspersed with gray, bleached, dead ones, some still standing, some long fallen. Here, as on all the islands we visited, the only sign of human life was the firepit near the obvious landing spot. We returned to our camp and spent the evening by the fire, eating, swapping stories, and watching the brightness of the day fade as the sun sank low to the west.

Leaving the comparative shelter of Satapetäjäselkä and sailing into the open waters of Sammakkoselkä, we continued without the mizzen and took in a second reef. We stowed the mizzen, oars, and Norwegian tiller as far forward as possible, so they were not in our way in the cockpit.

We awoke the following morning to cloudy skies and a light drizzle. The wind was still blowing 15 knots, so we continued with our reefed main and no mizzen, crawling our way north against the wind and the chop. Once more crossing the open water of the Satapetäjäselkä, we had plenty of space for tacking and NESSIE obediently rose up and over the waves, occasionally tossing spray over our heads.

As we reached the northern end of the Satapetäjäselkä, we were able to head northwest on a single tack along a wide channel between a group of unidentified islands to the north and the island of Kaamassaari to the south. For a while the wind eased, and we shook out the reef—for a rare moment we sailed under full main. But within 15 minutes the wind was rising again, and we took in first one reef and then a second.

As we approached a line of islands, just yards across, I suddenly spotted a rock dead ahead, and we threw in a hurried tack. We had misread the chart and were headed to an island south of the one we had planned to reach. We adjusted our route and came around one more island. To our north several mile-wide islands provided shelter from the worst of the wind, and we decided that, before we left them behind for the open water of Sammakkoselkä, we would stop for lunch. We pulled into an island the size of a tennis court and landed straight into a bed of moss edged by tiny crooked pine trees. We were both a little chilled and wet from the drizzle and spray, so we gathered up some dry branches and lit a fire. In minutes, we were being warmed by corn soup and toasted bread, and after cups of coffee and tea were ready for another challenge of open water.

As we left the shelter of the islands and rounded into the Sammakkoselkä the chop built quickly—we eased the sheet and fell off the wind slightly to maintain our speed against the building 4′ waves. We tacked across Sammakkoselkä a couple of times but were reluctant to continue fighting our way north. Instead, we decided to follow the route of a channel that threaded through a group of islands in the middle of the lake. We headed toward a cairn, a 6′-high pile of stones painted white, but as we came close, we realized there were two cairns approximately 1 mile apart and we were mistakenly headed for the more northern of the two marked on the charts. We rounded the head-shaped 300′-wide island called Head Spinner and turned south toward the channel.

On Varttasaari Island we found a sheltered cove for our third night. At the end of a long day’s sailing crouched in the boat, it was good to stretch out on a soft mattress. NESSIE was so close we could hear the wavelets lapping her hull planking.

As we dipped between the islands, the water immediately became smooth. The first island we passed to the south of us had one of the few cabins on the lake that are free for anyone to use, but the pier and shore were exposed to the northeast wind, so we sailed on by. Not much farther on, a sheltered bay on the coast of Varttasaari island opened up.

We rounded a headland and landed under sail, tying the painter off to a convenient pine tree and throwing out a stern anchor. The clouds were making way for clear skies; we spread our gear out to dry and bailed the small amount of water that had collected in NESSIE from the spray of the bow waves. I refreshed myself with a swim in the crystal-clear and pleasantly warm water, and sipped a beer, relishing its taste as I admired the unspoiled beauty and stillness of the bay and the channel leading southwest, its wind-tossed blue water framed by the rugged rocky beaches and ancient pine trees.

Near our landing spot there was a fire pit, and level dry ground on which to cook and camp. There were few signs of human life, no trash, just a small amount of firewood waiting for fellow travelers, as is the custom here in the northern lands. We strolled inland, through the forest. The sunlight threaded through the sparse canopy of the old pine trees illuminating the bed of crowberry, blueberry, and wild rosemary, their distinctive aromas rising up as we trod the bushes beneath our feet.

In a couple of small valleys where the air and ground were damper, cloudberry bushes joined the mix. The summer had been dry, so the berries were smaller than the tips of our fingers, but Inari nevertheless managed to gather enough for a good dessert. We also found some brittlegill mushrooms—a welcome extra ingredient for our dinner.

Leaving the sheltered Varttasaari channel, we entered the unprotected waters of Kasariselkä. This would be the windiest stretch on the windiest day of the voyage. Again, we sailed with a heavily reefed mainsail and no mizzen. Inari again switched out the Norwegian tiller for the fore-and-aft tiller with extension. She became expert at controlling NESSIE down the waves.

The morning was clear when we woke and checked the weather. The forecast was for 20 to 27 knots of wind continuing from the north–northeast. We considered our route and decided to avoid crossing Kasariselkä, the largest stretch of open water on the lake, and instead to turn south after the channel, where we hoped we would be somewhat sheltered by the large group of islands in the middle of the lake to the northeast. We packed up and left our camp under two reefs in the mainsail and without the mizzen sail.

NESSIE charged southwest down the channel—the water was smooth, the feisty gusts wiping the surface but not yet stirring up a chop. As we cleared the channel and turned south, we switched into our “survival” mode for rough downwind sailing: we dropped the main and tied the foot of the yard into the foot of the mast. With the yard thus held in place, we raised the halyard to hoist the head and uppermost third of the sail, leaving the boom and the rest of the sail in the boat. The small triangle of sailcloth gave us plenty of speed but lowered the center of effort so that we now had good control of NESSIE even in the hardest of gusts.

As we paralleled the dark-green coasts of Suovasaari and Varttasaari, Inari took the helm while I carefully followed our progress on the chart. From time to time we had to jibe away to avoid the shallows and rocks. With the scandalized sail we had to follow an intricate procedure to ensure that we maintained enough speed for Inari to keep control of the boat: drop the sail; alter course; lift the yard, boom, and sail over our heads to the new leeward side; raise the sail.

The strong winds forced us to switch to our previously proven heavy-weather sail plan. We raised the lug yard but tied its foot into the foot of the mast. This gave us a decent sail shape and enough power downwind, but we had to contend with the rest of the sail and the boom lying in the cockpit.

As we cleared the islands and shallows, our route now lay in the more open waters of the lower part of Kasariselkä. The waves grew bigger, rising to almost 5′, and NESSIE surged forward as she surfed down them, the water hissing close to the gunwale each time we rose over a crest. For a moment I glanced at the GPS—we were averaging 6.9 knots over the ground. As we sailed past the cairn on Vallenkari rock—a white wooden sign marked with the letter K—we jibed once more and set a heading of 160° toward another group of islands.

The conditions demanded our full focus. We were both excited and fueled with adrenalin, but nevertheless felt in control. At the tiller, Inari maintained her steady nerves, pulling firmly on the tiller as each wave picked up the stern and threatened to push us off our course. At last, we pulled into the moss-covered ledge on the shore of Vieppisaaret and I threw out our stern anchor while Inari tied our bowline to a small birch. In the shade of the pines and dwarf birch, we sat down with some refreshments and our chart.

As we snacked on salted nuts and dried fruit, we planned our next step. A relatively sheltered route through a group of islands, each little more than an acre in size, and Iso Jääsaari (Big Ice Island) to the south would lead us first southwest and then northwest to Suovasaari, an island with an outhouse and a simple cabin that was our destination for the night. The first mile would be in open water, but after that we’d be in the lee of the islands and should be able to maintain a close or even beam reach in the relatively sheltered waters.

We set off on a broad reach with just our reduced sail, but as we sailed, I worked on a better arrangement for the sail that would give us more power and greater stability when we came back to closehauled. I pulled in the second reef clew but brought the sail’s throat cringle down to the boom as the new tack. The resulting sail had the appearance of a small lateen. The clew was low and the boom very close to the gunwale, but we could sheet it in, and the sail shape was good. I was happy with it, but as low as it was, I knew it would not be a safe arrangement if we needed to jibe.

On Suovasaari we relaxed after a hard day. The wind eased, and we were sheltered by the island. For the first time that day we shed our foulweather clothes, and Inari took time to read the chart, considering where we had been and what our plans could be for the next, and final, day.

Once we were south of Hoikka Petäjäsaari, it was lunchtime. The island is almost 4 miles long but less than 1 mile wide; it rises to about 500′ above the lake and towers over its low-lying, diminutive neighbors. We anchored NESSIE and tied her up to a rock. The shore was steep and rocky, and we had to climb to find a flat spot on which to cook. From our height on the hill, we could see for miles. Crooked pine trees—some still living and dark green, others long dead, their gray and silver limbs contrasting with their healthy neighbors—framed the lines of islands and eventually the dark mass of the mainland, and all around, the windswept waters of the lake ranged in hue from gust-darkened steely gray to blinding white.

Refreshed by pasta, coffee, and tea we headed out once more and turned northwest under our jury-rigged third reef. Progress was slow, but island by island, we crawled onward to Suovasaari. At last, sailing up a channel no more than 200 yards wide that led straight upwind, we approached the pier and cabin. The wind funneled down the channel tossing us back and forth. We decided to cut our losses and to land instead on the southwest shore of the island some few hundred yards away.

We still had to tack up to the shore, so we shook out the third reef to improve the sail’s set and our performance, and headed in. We tied the bow to a gray, semi–submerged tree stump that had been cut off below its branches but still had its roots planted firmly in the rocky bottom of the island’s shallows. Once more our landfall was sloped and forested, and it was some time before we found a flat spot where we could pitch our tents. The dull gray clouds were at last breaking up, and in our fatigue from the day we welcomed the warm rays of the evening sun. After dinner I crawled into my tent, sheltered from the elements by the pine trees growing up the steep hill behind us. Out of the noise of the wind and separated from the sounds of the waves, I relaxed, perhaps for the first time that day, and slept the sleep of the carefree.

The following morning was again overcast. The forecast was not what we had hoped for: 20 knots of wind with gusts of almost 30 knots expected through the morning. But it was still early. We decided to take things easy, slow down for a few hours, and leave later in the morning by which time the wind should have died down a bit. We were not far from Veskoniemi, where we had launched and where we would pull out. We could have gone straight there, but I suggested that when things had calmed down some, we could extend our day’s sail by going just a couple of miles farther northwest to visit Ukko (the Old Man), an island sacred to the Sámi people. Ukko is only a couple of hundred yards long but climbs steeply to a height of 98′, giving it a distinctive appearance amongst the mostly low-lying islands of the lake.

After 10 a.m. we set off to the west with two reefs in the main. On a broad reach, NESSIE charged through flat waters but strongly gusting wind. Soon we were approaching a gap through a group of islands from where we hoped to catch a glimpse of Ukko. I looked at the chart to establish our position and realized I had been in error: there was no way we would see Ukko from here; it would be totally obscured by an adjacent island, Palo-Ukko. To catch even a glimpse of the Old Man we would have to sail once more into open water, but the wind was still strong, and the gusts were severe. It would be foolish to leave the comparative shelter of our island passage. We turned back. Ukko would have to wait for another time.

Once more, we reduced sail to my improvised third reef. Now we were tacking rather than jibing, and the maneuver required careful execution and timing. Inari steered, and when I thought we had enough speed to keep our way on against the wind and vicious chop, we would tack. In the eye of the wind, I loosened the sheet, raised the boom with my hand, pushed it against the wind to backwind the sail and force NESSIE around onto a new tack. Then I would lift the boom over myself and Inari, and we’d set sail on our new heading.

It worked well, but the timing was critical. On one tack, we were approaching a rock and a shallow to our lee and agreed that it was time to turn again. I made ready, shouted to Inari to go for it, felt the bow turn toward the wind, prepared to back the sail, but… at the last minute a wave stalled us; we didn’t make it into the eye of the wind. We were in danger of getting into irons.

We needed to fall off, pick up speed, and try again. But there was no room. In a split moment I made the only choice open to us: we had to jibe. I yelled at Inari and with no hesitation she pulled the tiller hard to windward. As the bow fell off, I remembered the third reef: the boom was low; it would be as a scythe coming across the boat. As I struggled to think what to do, a gust of wind whipped the sail and boom across the boat with a speed and violence I never wish to see again. To this day I am haunted by what might have happened; to this day I cannot figure out why neither of us was hit.

We came into Veskoniemi and pulled up alongside the dock under full mainsail. It had been an exciting few days and we were tired, but Inari, NESSIE, and I had made a good team.

We came through the jibe, rounded up, and continued on a new tack. Dumbfounded by my recklessness and shaken by the near miss, I lost track of our position on the chart. About 2 miles to our east, we could see a cairn. Taking a bearing and praying that I knew what I was looking at, we reoriented ourselves on the chart and considered our route. If we sailed east toward the cairn we would pass through a maze of shallows and islands, but there was a safe channel (albeit a narrow one) and we could get to the cairn in one tack. We went for it. I breathed more easily: our tacking duel with the wind was over.

As we came to the cairn, we fell off onto a beam reach and toward the even more sheltered channel between the mainland to the southwest and the 4-mile-long hilly island of Mahlatti to the northeast. We pulled into Mahlatti for a late lunch. From here to Veskoniemi there was but one last hop of a couple of miles, along which we would be sheltered by the hills and forests of Mahlatti. For the last time, we pushed off under one reef. Before long we shook out even that one. Under full sail NESSIE carried us to the Veskoniemi dock, heeling only occasionally in a stray gust that made it through the Mahlatti forest. It was a fitting end to our time on Lake Inari. We were tired, windblown, and wet but we were happy with ourselves, with each other, and with our steadfast boat. In the last mile, NESSIE steadily gained speed, and as we pulled into Veskoniemi her bow was slicing effortlessly through the arctic water.![]()

Mats Vuorenjuuri is the father of three and has been an entrepreneur making a living in graphic design, photography, freelance writing, and most recently as a boatbuilder, offering boatbuilding and maintenance services through Nordic Craft. After sailing various types of vessels, including sail-training schooners, he enjoys the simplicity and pleasures of small boats. He wrote about cruising the Finnish coast in his Coquina in our May 2016 issue, a Lakeland row in January 2017, and an archipelago cruise with Inari in March 2022.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Thanks for sharing this marvelous adventure. It must be heavenly to cruise where wild cloudberry can be gathered for a snack!

Thank you for taking the time to read it. It takes some effort to reach Inari lake, but it is worth the drive.

Mats,

Your adventures with Inari are an inspiration. It is a welcome reminder to get my Caledonia Yawl out on the water, with my own daughter, Fiona, now 20.

Thank you, you have chosen an able vessel for your own adventures.

For Finnish readers, there is an interesting book ‘Isoa Inaria kiertämässä’ written by Antti Tuuri and Erno Paasilinna. They had a slightly smaller wooden one-masted boat and recalcitrant outboard. The book has some history, description of landscapes etc, and they have a longer route through the lake——it hasn’t been translated into any other language from Finnish.

I am married to a native Finn from Kuhmoinen, and I love boating on the lakes of Central Finland. This adventure on Lake Inari seems wonderful. The boat is beautiful and reflects the Finnish inherent love of wood. Kiitos.