Bands go on the road; mom/artist types with a kid in tow usually do not. But I sorely needed to look at life from a different vantage point, and to reconnect with beau and babe in a not so 9-to-5 way. So we cut through all of the excuses not to, and went off adventuring.

There was, of course, a year of planning and waiting while the mountain of anchors and spare tires and expired safety flares grew in the garage. But on a rainy, windy November day we hitched FIG, our 15′ skiff, behind IDA, our unpredictable ’69 Chevy van, and rolled away from Seattle, headed for Mexican skies and the Sea of Cortez. The windshield wipers quit about an hour into the rainstorm. But, hey, we were going to Mexico, so a little Rainex and we carried on.

Joe Talbert

Joe TalbertOn our way south we killed off our Seattle mossyness with some climbing in the boulders of Lone Pine, California, at the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Our boat generated many strange glances in the high country.

We trundled FIG along up desert dirt roads, parking among chalk-smudged climbing boulders and next to hidden hot springs. She got to wet down briefly, and only after rigorous inspection, in the great blue waters of Lake Tahoe, and later, after a flash rainstorm, became the only boat that ever needed to be bailed in Joshua Tree National Park. At one point FIG found herself feeling underdressed in the parking lot of a swanky Palm Springs hotel, but then finally, finally, made it over the Mexican border, and to the sea.

We were calling it my son Ely’s gap year. He’s a September birthday so he didn’t make the cutoff for kindergarten, but he had done a few years of preschool already, so why not take him on the road before there were school secretaries to give you the stink-eye about family trips and soccer games that can’t be missed?

Our plan was to put in just south of Puerto Escondido at a little empty beach, and then I’d wait with the boy while my husband Joe drove overland to Todos Santos to leave IDA and trailer in a friend’s yard for the duration and take the bus back to us. He left early, and Ely and I were alone with our boat on the sand and our tent in the bushes.

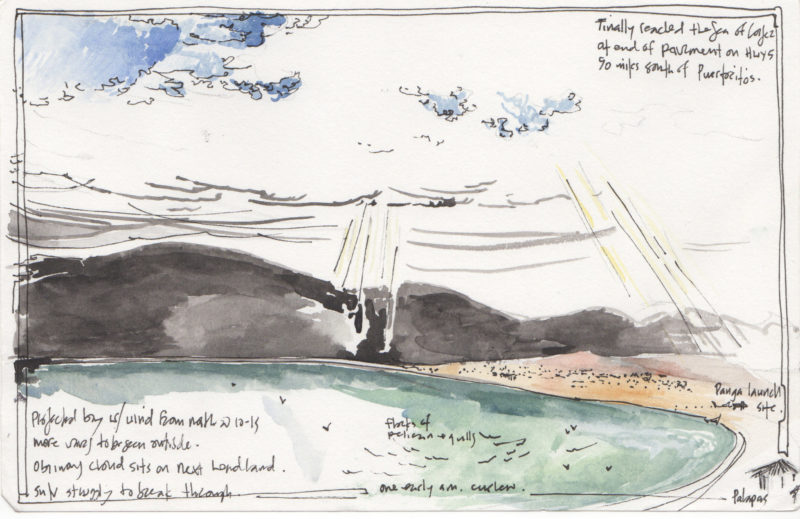

Hannah Viano

Hannah VianoAfter a long drive south, I stole a moment to sketch our first contact with the sea. There was still a lot of bumping along crazy Mexican roads to do, but the dramatic scene was cause for celebration.

The beach was scattered with sweet retirees in campers and RVs. Some of them had run to our aid, unbidden, when we got the van stuck in the sand while launching FIG. Word of our story and our plans had spread, and many folks swung by to offer help and let us know we could come on over if we had any trouble. The only trouble was a rogue bed-wetting incident on our first night in the sleeping bag sack system. Aarghhhhh. That and the near heart attack I had when Joe stumbled in at 3:00 a.m., having made great time and walked the last few miles.

Joe Talbert

Joe TalbertLoaded to the gills, our little FIG still had plenty of freeboard but no free cockpit sole to speak of. As the coastline we intended to sail had only small villages, we packed most of the food we needed for the entire trip, with stops for beer and water when available. Sticking out over the gunnels are the custom bronze pieces that the leeboards slide onto. They are then screwed down tight with small handles that we miraculously managed to avoid dropping in the sea.

We pushed the boat down to the water and started piling the gear in. And piling, and tucking, and before we knew it there was almost no place for three bodies to sit. There was camping stuff, cooking stuff, fishing stuff, food for a few weeks and water for one week, even a small guitar and toys. Though in this mess the teensy dry bag that I told Ely was his allotted space for toys made me laugh. He had done great at packing to fit; Joe and I, it seemed, had not done quite as well.

Anyway, it was all in there, and the neighbors were trying to give us more stuff every minute so we needed to get off the beach. You know that feeling when there is momentum started and you just need to keep going, or it feels like you will never be able to get rolling again? Even after we were finally loaded, they were calling out more things that we needed to have.

Joe Talbert

Joe TalbertFurling sail after riding the surf in on our first day out, I looked at the wind driven waves and wondered what conditions were to come. We had scheduled the voyage around our outside lives and responsibilities rather than weather patterns, but later locals all agreed that December was notoriously windy in the Sea of Cortez.

With the wind up we were soon screaming off along the beach. Our goal was a small cove, only a few miles down the way but well away from the road and neighbors. At one point we thought landing on the lee side of a small islet might prove smarter than taking a chance with waves breaking on our intended beach, but that option didn’t pan out and we did our first of many high-action surf landings. We threaded the needle between rocks and landed with all our gear still aboard. Ely immediately got naked and ran around looking for prize sticks and chasing seagulls.

Joe Talbert

Joe TalbertAfter a beach landing, Ely would always leap out and run off to splash in the waves while we used our inflatable fenders to roll the boat up beyond the tide line. The fenders proved to be some of our most crucial pieces of gear.

Our first time getting FIG up the beach, we realized that almost everything had to be removed in order for us to roll her on the fenders up above the tideline. We got better at this over time, and one person would jump out of the boat prepared to stand in waist-deep waves and hold FIG in place while the other shuttled back and forth with leeboards, mast, dry bags, water bags, etc., etc.

The weather in those first days was a fluky mix, with much wind at times and smaller breezes that seemed to change direction on a whim. We’d later come to recognize patterns, important because after getting beyond radio range of Puerto Escondido there were no weather forecasts to be had.

Hannah Viano

Hannah VianoEly’s toy bag was tiny but he never had a shortage of interesting things to play with. During a windy layover we all helped put together this exotic waterfront shack.

After leaving an idyllic beach and tearing into a much less idyllic, rocky one the previous day, we were motivated to find a better spot, and when dawn broke calm, we saw our chance. We pushed out, and the swell that had risen up the day before was greasy smooth. A bunch of dolphins swam with us and then, in an odd and ominous way, headed in the opposite direction. Hmm. Two hours later the wind and swell built too much and we were sailing on a fast and furious broad reach toward a distant shore that seemed to have huge waves washing up on it. The only other option was to clear the point at the end of that beach and try to tuck into the teensy bit of protection that might have been had on its far side. This point was the lee shore of all lee shores, a tall ochre-bluffed peninsula that tapered out into a gnarly black rock cliff and barely connected islets strewn with jagged rocks.

Needless to say, we put on our life jackets. The ditch kit was close to hand and those hands were clamped tightly on the tiller and the sheet. FIG has a simple setup for sailing without much in the way of mechanical advantage. The sheet usually leads to a pin in the thwart, though it was around the thwart now, and back to Joe amidships so he could be near Ely. This child has an awesome ability to know when a situation is intense and just hunker down. Had he been the squally, panicky type we could have been in serious danger, but instead he was curled up in his life jacket, tucked under a sheltering yoga mat and possibly even asleep.

By now we had made the precarious removal of the sprit, which meant a weighty adult had to go all the way out on the bow—not what we wanted to do in this downwind, following-sea situation, but we did it. Luckily, clearing the point was no problem, and with the wind at our stern, we just held our breath that the waves would treat us well. Joe and I were at odds about when to take in the sail. I wanted all speed possible to get us out of the waves before we took a big one; I was at the helm so we held out a bit longer and then struck the sail. We still had quite a bit of speed on with just the bare pole. We got the oars out as we cleared the point and headed for the closest bit of sand. When we finally got into a tiny bit of lee and had our four oars in the water, we breathed a little more deeply, but only until we saw a couple of menacing black fins flick in the water next to the boat. They were not too big, but it seems they wanted us to know they had their eyes on us.

As we neared the bit of sand we could see it was rocky. There was another beach in a notch at the base of the point, but it was upwind and tiny. The rocks and big surf we were approaching were definitely bad so we put our backs into the rowing, and fought our way upwind to the other beach. We made it and it was indeed a mere scrap of protection. We pulled FIG up as far as we could and sat slumped in the lee of the hull, cold and questioning our parenting choices. Ely was frolicking at this point, while we took a couple swigs from our tiny emergency flask and toasted: “To being lucky this time and smarter the next!”

Joe Talbert

Joe TalbertFrom our planned launch site tucked in the bushes we could just see the masts of the yachts in the protected harbor nearby, and it was an exciting reminder that our voyage was a very different sort of cruising.

We ended up stuck on that bit of beach near Punta San Telmo for five days, with winds out on the water in excess of 40 knots and huge waves rolling even into our protected notch. As the seas built and the full-moon tides rose higher and higher, we moved our tent and the boat up and up until we hit the wall of the bluff. After a few days of lounging and lovely hikes among the desert wildflowers, we walked over to a fisherman’s house that we’d spotted from the boat. Our conversation was in stilted Spanish, but we came away with water and homemade cheese and little old abuela’s fresh tortillas. The tortillas looked so amazing we scurried only a short distance down the trail before sitting in the dirt to devour some.

Hannah Viano

Hannah VianoCamping on the beach our two challenges were wind and sand. And, of course, wind-driven sand. One positive of unloading so much gear from the boat every day was that we could make a windbreak wall with our drybags and other gear.

On our last day at the little cove we hiked to the south to check out a more welcoming anchorage we had seen on the map, a photocopy of a road atlas that turned out to be the most accurate of the various references we’d found. While we were eating lunch on the beach, in sailed some folks on a small wooden sloop. We had met them earlier in the trip and they swam ashore to chat, bringing news that the weather forecast was looking up.

Hannah Viano

Hannah VianoThe boat’s leeboards often did double duty as galley tables. After a few years trying to fall in love with them in their role as an alternative to a centerboard, I still like them best as furniture.

For the last week we had been scanning the horizon and checking the radio in hopes of connecting with some Seattle friends who had bought a beach catamaran (in Loreto, via Craigslist, sight unseen) and flown down with epoxy and extra line, ready to sail down the coast hoping to cross our path. We assumed that with all of the wind they’d be far ahead by now, but then as we sat on the beach finishing our tuna and crackers, we spotted a sail a ways offshore. It was a small colorful sail, such as a beach cat might have. There were few small-boat cruisers in these parts, so we assumed it was our friends and jumped up and down screaming and yipping and calling on our handheld.

No reply.

Our friends out on the anchored sloop heard our radio calls and blew their air horn, but the little sail kept right on going.

By now we were all fired up so we raced back overland to our beach. Tiny Ely was a trooper, jogging through the cactus-strewn hillsides on short legs at full speed and then helping as we ran back and forth down the beach to the boat throwing gear aboard. Our beach camp was down in minutes and we were rowing out into the now diminishing swells. It was dusk by then and since we weren’t quite ready to sail on into the dark in the still-large seas, we turned in at the anchorage and dropped our hook next to the sloop for a cramped sleep in the boat with all our gear.

In the morning we woke early, knowing that our last chance to catch our friends was if they had stopped that night in Timbabichi, a small village a few miles along. We rowed four oars for all of we were worth, singing and wishing and hoping as you do when a nice thing has built up in your mind to wondrous proportions.

As we rounded the last headland, it looked as though the beach was empty. Oh, our hearts sank. But no, tucked into the farthest corner of the harbor and already being loaded for travel was the beach cat. HHHHHHOOORAAAY!!!!!!!! Jake and Jean welcomed us with equal whoops and cheers of surprise. They had seen people on the beach, but as they hadn’t seen FIG they assumed we were somewhere far ahead.

Joe Talbert

Joe TalbertOur camp near Punta Ballena typified our overnight stops, with a pebbly beach fading off into fine sand at the base of steep cliffs. It offered an excellent hike up a drainage filled with blooming desert plants.

Over the next couple weeks, as rounds of wild weather came and went, we sailed past gorgeous multicolored cliffs and into tucked-away coves. One anchorage in the village of San Juan de la Costa found us wading through the shallow water of a red tide of fish guts for an unfortunate campsite next to the reverse-osmosis plant. Most others were pristine beauties with dorado jumping in the surf at water’s edge.

Eventually, north of La Paz, as the beach tapered off into industry, we spotted our little white van and empty trailer trundling up the dirt road with my father at the wheel. My parents scooped us up and we headed off to a beach-house rendezvous with a bunch of friends and family for Christmas.

The end of an adventure is always bittersweet for me. I want to keep going as much as I want a shower and a hamburger, and I always worry that we might not get another chance to do something like this. It was a long, slow re-entry as we towed the boat back north, wetting our bows one more time in back waters north of Bahia Magdalena to tack gently back and forth across the narrow channel as gray whales made their way slowly past.

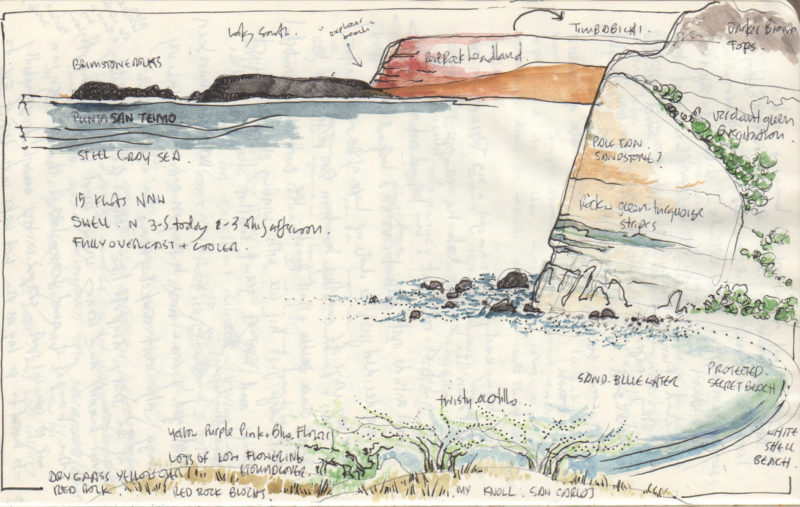

Hannah Viano

Hannah VianoLooking south at the black Punta San Telmo that we would later round in adverse conditions. The different colors of the sandstone cliffs continued to amaze us the entire trip, passing from yellow and ochre into greens, whites, and even a stunning violet that was positively otherworldly.

FIG ended up staying in Tahoe where our friends had been scheming to purchase our boat should we make it back that way. So she is sailing blue inland waters and nuzzling granite beaches, while we are trying to figure out what the postman has done with the Ness Yawl plans that should be on their way from Iain Oughtred in the Isle of Skye. Ely, when asked, will tell you that he doesn’t like sailing, but when we sold the boat there were tears. “How will we go on another adventure?” he asked. “Don’t worry sweets. We’re working on the next one.”![]()

Hannah Viano is a writer and artist living in Winthrop, Washington, and her adventures have taken her from Ketchikan to Cape Horn. Samples of her work appear on her website: hannahviano.com.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Wonderful. wonderful story. A beautiful adventure in a lovely little boat. And you will love your Oughtred yawl, for those boats are real champs. I too adore the spritsail, and would not have anything else on a boat under about 23-25 feet. Thank you so much for sharing this story.

Thanks so much for sharing your story and your wonderful sketches/paintings and photographs. What a super experience for Ely—the three of you will never forget it. I hope you have experiences in your yawl that are as wonderful. What will you call her? I look forward to the next installment and the building of the yawl.

Thanks for this. I enjoyed the story, and the illustrations add a dimension that photos can’t match. Baja is on my list of “someday” sailing destinations.