In 1936, Kenneth With bought a 24′ cabin cruiser, secondhand, for $595. It had a compact but comfortable cabin, just right for taking his young family cruising among the myriad of islands of Ontario’s Georgian Bay. The cruiser, BLACKDUCK, needed a tender, and in 1945 Kenneth consulted with his son, Ritchie, who had already taken an abiding interest in wooden boats at the age of 10. The two looked over the boat design catalogs Ritchie had collected and decided on the Bantam Pram, a 6-1/2′ plywood rowing boat designed by Charles G. MacGregor in 1939.

Photographs courtesy of the With and June families

Photographs courtesy of the With and June familiesThis volume in Ritchie’s collection of catalogs provided the plans for the Bantam Pram, Design No. MM-10 by Charles G. MacGregor.

MacGregor was a prolific designer of boats large and small; between 1906 and 1949 he published 58 designs in The Rudder magazine. From 1930 on, most of his designs were intended for plywood construction, breaking new ground in boatbuilding. The 25′ Sea Bird Yawl is one of the best known from this period.

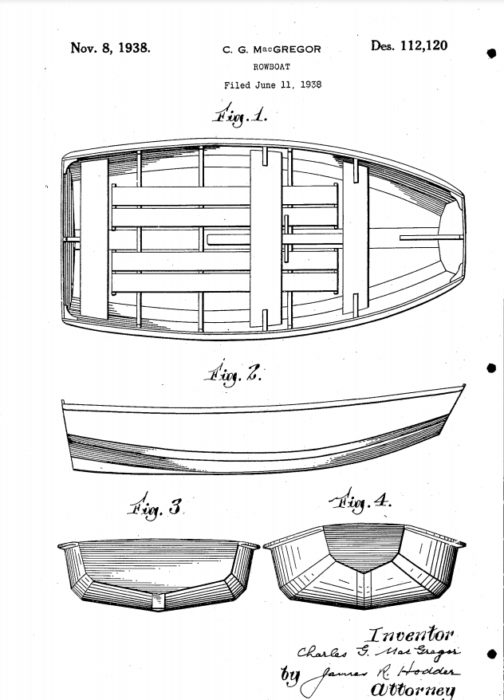

MacGregor’s design patent for the pram provided 14 years of protection for the form and appearance of the boat. It’s not a utility patent protecting the idea of a pram.

The plans for the Bantam Pram note, in handwritten capital letters: “THIS DESIGN IS PROTECTED BY U.S. PATENT.” The patent for the boat appears to be Design Patent 112,120, granted in 1938, stating: “Be it known that I, Charles G. MacGregor, have invented a new, original and ornamental Design for a Row Boat.”

In 1945, Kenneth ordered Bantam Pram plans and materials and got as far as cutting out the plywood panels before setting the project aside. A salvaged dinghy was pressed into service as BLACKDUCK’s tender. The plywood pieces were squirreled away in the With family home (then near the shores of Georgian Bay), and later moved to a new home in Toronto on Lake Ontario, then to Midland on Georgian Bay, and finally to Sarnia on Lake Huron. The parts of the pram were always near the water, but the boat was never built. Kenneth passed away, Ritchie grew up and had a family of his own. His son, Greg, grew up, married Tammy June, and they had four children: Logan, Sawyer, Sarah, and Jasper.

One afternoon, early in the pandemic, Tammy and Ritchie were visiting in their back yard, and Ritchie recalled his fond memories of boating on Georgian Bay and spending summers at the With family’s island retreat. He mentioned the Bantam Pram, his father’s unfinished project. Tammy was well acquainted with the plywood pieces, having helped to haul them with each of Ritchie’s moves. When Ritchie expressed an interest in seeing the boat built and launched, Tammy saw it as both an opportunity to occupy her kids during the pandemic and a way to connect them to their grandfather and even the great-grandfather they never knew.

On the first day of construction, Ritchie and daughter-in-law Tammy examine the plans and decipher the pieces rescued from the garage attic.

She wasted no time in getting the ball rolling. She located Kenneth’s original plans and asked her husband Greg to retrieve the pieces of plywood from Ritchie’s garage attic. There were no instructions and no one in the family had any boatbuilding experience, so they watched a lot of online instructional videos.

The last time Ritchie, left, worked on the boat he was ten years old. Tammy, right, is the principal boatwright and her daughter, Ritchie’s granddaughter, 4-year-old Sarah, supervises the project.

Sawyer is the first of the grandchildren to try his hand at sanding. He works his way along the center edge that will be drilled and stitched together.

Tammy set up shop in her family’s back yard in a space bordered by the garden, garden shed, and swing set. Her two older kids helped at times, but their attention often wandered and Tammy’s motherly tasks limited her work to small windows of time. The boatbuilding lurched along in five-minute increments.

The pram was designed for construction over eight molds set on a strongback, but the stitch-and-glue plywood method they’d seen in the videos seemed like a quicker way to get the boat built. Kenneth had cut the bottom and the side panels, but there was no sign of the 3″-wide plywood chine pieces—the element that likely had given MacGregor’s Bantam Pram the distinctive shape he had patented. The budding With family boatbuilders, given their study of stitch-and-glue construction videos, can be forgiven for mistaking the measurements on MacGregor’s half-breadth drawing as a pattern for the chine panels; they cut curved pieces from new plywood. The pieces would have, in fact, been nearly straight, and would have taken their shape on the molds.

Frustrated but determined, Tammy attempts to attach the chine to the bottom panels. Soon after, the chine was removed and the side panels attached directly to the bottom panels.

The chine piece—laid flat and nearly parallel with the bottom panel when the two were stitched together—was clearly not the right shape. Not one to give up, Tammy decided to forge ahead without the chine panel and stitch the bottom directly to the side panels. The edges went together as if that’s the way it was meant to be. The pram would be a bit narrower and have less freeboard, but better that than abandon the project.

Time had taken its toll on the old 1/4″ plywood. It yielded easily to the drill bit making holes for the cable ties, its edges were rounded soft, and it was thinner than the new 1/4″ plywood. Tammy decided to fiberglass the hull and give its exterior two layers of ’glass to restore some of the strength that the old plywood had lost. After the seams were all stitched, Tammy called on her father, Rick June, to help with filleting and taping the joints.

Rick and Tammy apply the first layer of boat cloth on a steamy August morning.

Rick’s professional experience working with fiberglass came in especially handy on the day for the fiberglass sheathing. It was the hottest day of the year, approaching 90 degrees, and the work had to be done quickly before the epoxy kicked. With Rick’s help, they got the job done. Days of sanding and painting followed. Sarah, the youngest child and the only girl in the family, pitched in wiping the hull down after sandings.

PUDDLE DUCK waited 75 years from the beginning of her construction to her launching.

Sawyer and Greg take PUDDLE DUCK for her maiden voyage. She needs a few adjustments to get her to float on her lines.

Rick, left, and his son Derek carried PUDDLE DUCK back to the van after her launching and first trial.

The kids decided on PUDDLE DUCK for the boat’s name, and the With and June families gathered on September 5, 2020, to launch the pram at a park pond. Before the boat took to the water, Ritchie, now 84 years old, gave a speech about its origins 75 years ago and then he and Tammy christened the boat with a splash of sparkling cider.

His son Greg and grandson Sawyer rowed together on the maiden voyage. Sawyer couldn’t be pried out of the boat and stayed aboard while others took their turn with him. The kids—all of them Kenneth’s great-grandchildren—took advantage of what remained of the warm weather to get PUDDLE DUCK afloat. One neighbor had a pool, so the boat was secured to a wagon and Sarah took it in tow there with her tricycle.

Sarah towed PUDDLE DUCK with her tricycle to her friend’s pool. She captured the interest of many passersby as she pedaled down the street in her pink dress.

Tammy enjoyed building PUDDLE DUCK and has been looking at plans for a boat to build with her father next summer. MacGregor’s little Bantam Pram may only be 6-1/2′ long, but this one has bridged four generations.![]()

Do you have a boat with an interesting story? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share it with other Small Boats Magazine readers.

Ah, the PUDDLE DUCK—what a grand tale, testament to getting the boat afloat vs. floating a perfect boat. How about a Wineglass Wherry from Pygmy (if they survive)* or a Chesapeake Light Craft wherry?

*Editor’s note: The Pygmy website states: “Our Showroom is CLOSED. Kit production has been temporarily suspended. If you are interested in a boat kit you may place an order via our website. We will not charge your credit card until production has resumed and we have confirmed you would still like the kit at that time. By placing an order before then your order will be put in the queue for when production resumes.”

I have a wherry I built 18 years ago. It’s still not finished but on display attached to a high ceiling. This is inspiring.

More than 60 years ago, I built a little pram, very like this one, for my dad. It was a 1945 Al Mason design that I found in “The Rudder.” It even had the V bottom and beveled chines, which proved to be the most challenging part. I laminated the chines, though they were a solid stick in the original specs. It called for 4 mold frames, plus transoms at each end. It also specified a single frame amidships, 1/2″ x 3/4″ steam-bent on edge. Lacking steaming equipment (and white oak being “unobtanium” in the town of Chelan in those days), I laminated that frame out of thin strips of Doug fir. I was able to find 3/16″ fir plywood for the planking, though Mason said you could use anything from 1/8″ to 1/4″. Today I would use 4 mm okoume in a marine grade, which is much superior to the fir.

The seat was T-shaped, with the leg of the T running fore & aft, and the cap on the T toward the bow transom. This proved to be an excellent arrangement. Even with my long-legged uncle on the stern seat, it went really well with me rowing from the bow. In fact, this little boat was the best-rowing of all the little dinghies I ever had. I think a lot of that had to do with the beveled chines.

I also built a couple of Atkins’ Tiny Ripple prams, which were even smaller, being only 6′ long. They didn’t have the V-bottom, nor the beveled chines, and the bow transom was much wider than the PUDDLE DUCK’s. I used to tow one of these behind my little 21′ wooden Ed Monk cutter of 1935 vintage. One time, under perfect conditions on the Strait of Georgia, the dink was planing and throwing up a rooster tail. A couple of harbor porpoises picked us up, and one dropped back to check out the dinghy. The little Atkin prams were also excellent rowers. What a contrast to the rubber donuts that are ubiquitous now. I’d not want to be in one of those things in a blow, and with a dead motor, and the little vestigial aluminum “oars.”

This looks like a great project. Are the plans of the original design still available?

Chris Cunningham, can you answer that question about the plans?

The only design from Charles G. McGregor I’ve seen that is still available is his Sea Bird yawl. I looked online and found a copy of what appears to be the catalog that contained the Bantam pram plans. I ordered it and if it has the plans, I’ll see if I can send scans out.

Uh-oh….sounds like Tammy may have caught the boatbuilding virus. No vaccine for that one. I love this story and congratulate Tammy and her crew. I have a boat that needs moving, and I’m hoping Sarah is available for hire.

What a wonderful story, we’d say that boat is Perfection x 4 (generations).

Huzzah

Skipper and Clark