When I made the spars for my Caledonia yawl in 2005, I decided to lighten the largest of them by making them hollow and give the bird’s-mouth method a try. It was a lot of work milling eight staves for the two masts and the yard and the boom for the lug main spar, but I was pleased with the results. They were quite light, most notably the mainmast, which I had to lift high to slip though the foredeck—it was a cinch to step.

It didn’t take me long to notice something unusual about the mainmast when I was sailing. Its halyard wasn’t always where it should be, snug against the mast. It tended to move away, as much as 3″. This puzzled me because it seemed that the halyard was moving, even though I knew it was quite taut. I eventually realized that the halyard was staying as straight as a bowstring, and the mast was bending away from it. At 19′ the mast was the tallest I’d ever made, so I accepted that some flex was meant to be. Still, there were times when I nervously watched the gap between halyard and mast pulse and widen.

I was sailing across Puget Sound with Sharon, a new girlfriend at the time, and we had made a brisk crossing on a broad reach from east to west and had turned around to head back. On the new course I had to haul the sheets in and point higher. We were making very good speed, but the gap between the mast and halyard was wavering between 3″ and 4″. A fast-moving tugboat crossed a few hundred yards ahead of us. Its wake had smoothed a bit by the time it reached us, and the bow climbed over the first wave easily, but after the bow rose to meet the second wave, it fell heavily into the trough. The mast exploded with the report of a shotgun blast and broke in two, about 5′ above the deck. The sail fell overboard and we came to an abrupt stop. Sharon looked at me with her eyes wide. I shrugged and said, “It looks like I have a woodworking project for next weekend.” With the sail aboard and the spiky stump of the mast unstepped, I got out the oars and rowed us home, a distance of about 3 miles.

I did some more reading on bird’s-mouth spars and found one bit of information that I’d missed: When a spar is made hollow, its diameter needs to be increased to give it the same strength as a solid spar. I wasn’t going to make the hole in my foredeck any larger for a new mast, so I made the replacement solid. It’s a lot heavier and a chore to raise and lower, but having a mast that stays where it belongs, snug against the halyard, is a comfort when the big lugsail is drawing hard.

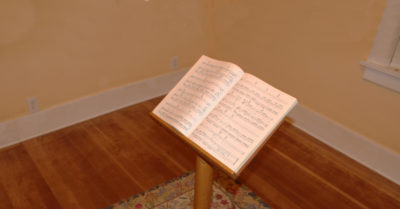

I’d put too much work into the bird’s-mouth mainmast to be happy scrapping the whole thing. I sawed off a 4 -1/2′ section of the upper half, cut away the plugged top, and used it as didgeridoo, a rather poor one; and with a portion of the bottom half of the mast I made a stout, unwavering music stand.

![]()

That’s real nice, maybe mount two small wooden cleats down low. Glad neither one of you got hurt when the mast came down.