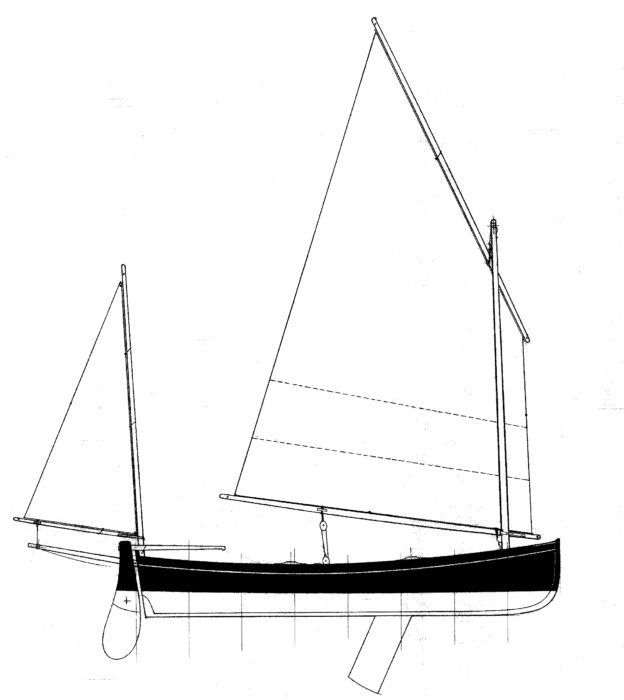

About 20 years ago, Long Island, New York, boatbuilder and designer Paul Gartside was commissioned by Steve Doherty, a publisher of marine books, to design a boat he could build in his retirement. Steve lived on Shelter Island on Long Island Sound and, Paul told me, “was a bit of an Anglophile and loved the British workboat types, so the resulting design is just a typical small beach boat of the type that was common throughout the British Isles, especially in the West Country, 100 years ago.” Typically, those boats carried mizzen sails, mostly to help them tack, and didn’t have centerboards. “It did concern me,” Paul noted, “that without a board, it would be slow to windward and there would be too much reliance on oars.” So, the addition of the board was the only significant difference in Paul’s design. As it turned out, Steve never got around to building his boat, and it is only recently that the first one built to this design has been completed.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe square hole in the transom is for the mizzen’s boomkin, which extends 4′ from the transom. The forward thwart is designed as a rowing station, though oarlocks are not installed here. The line at the aft end of the centerboard trunk is the tail end of a gun tackle on the port side of the trunk, which provides the mechanical advantage needed to raise the galvanized steel-plate centerboard.

When Kate Abernethy enrolled at the Boat Building Academy (BBA) in Lyme Regis, England, she arrived with an old Wayfarer dinghy that she hoped to restore as a course project. But when the Wayfarer was found to be beyond repair, she decided that she would build a new boat. Kate wanted something that would be trailerable and around the same size as the 16′ Wayfarer, and she liked the idea of a lugger. While searching online, the Gartside Centerboard Lugger, Design #124, caught her eye. “It just looked perfect,” she said. It would be well suited to learning about building boats as “it had all the boatbuilding joints you would want to know. It would be challenging with lots of problem solving.”

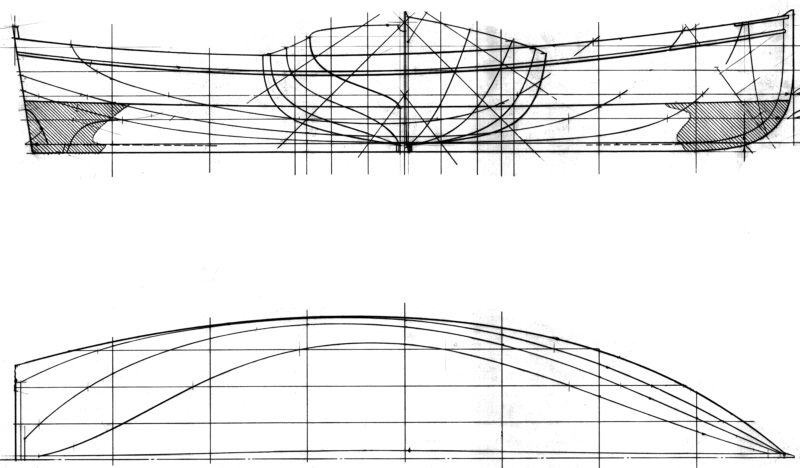

During the lofting process, there were concerns that there wouldn’t be room for the landings of the planks on the sternpost, and so its siding was increased from 2″ to 3″. Other than that, Gartside’s six sheets of clear and detailed plans were followed fairly closely. The centerline structure consists of a 4″ x 2 1/4″ fir keel (Kate used oak for hers and laminated it from three pieces for more economical use of the timber), an oak stem made up of three pieces scarfed together, and an oak sternpost, with a knee. Although Gartside prefers building the hull upside down—“because it is so much easier having gravity on your side”—Kate decided to do it the right way up “because I was inexperienced and it would be easier to ‘see’ the boat during the building process.” Once the 1-1/8″-thick oak transom and seven temporary molds were set up on the centerline, 11 ribbands were run around each side. Then 5/8″ x 1″ oak frames on 6″ centers were steamed and bent between the molds inside the ribbands. (If the boat is built upside down, the timbers would be steamed outside the ribbands, with a corresponding reduction in the dimensions of the molds.) Most of the frames run gunwale to gunwale, but three aft, four forward, and nine in way of the centerboard case are in two parts with their ends boxed into the centerline components.

The carvel planked hull has steam-bent oak frames on 6″ centers. The 3-1/2″ wide brace across the top of the transom serves as a partner for the mizzen mast.

For the planking, Gartside specifies nine strakes of 1/2″ red cedar, laid carvel, with red-lead putty in the seams and with a yellow-cedar lapped sheerstrake. Kate planned to store her boat on a trailer rather than on a mooring, and she was concerned that it would dry out during any long periods between outings. To keep the seams from opening up, she decided to use Accoya for the planking, and to glue the planks to the ribs with epoxy as well as riveting them, and to glue the seams as well. Accoya is a material that originates as radiata pine in New Zealand but then has its structure modified by a process called acetylation. This process reduces the timber’s hygroscopic properties (the ability to take in and expel moisture) and increases its stability.

The planks in the lower part of the hull at the bow and stern are required to twist as they are bent in place, so it was necessary to steam some of the planking. However, it was found that Accoya wouldn’t steam as well as more conventional timbers, to the extent that for the aft third of two of the strakes, oak had to be used instead and was scarfed onto the aft part of the Accoya planks. Kate also used oak for the sheerstrake, as it was to be bright finished, and laid it carvel rather than the lapstrake specified. Once the planking was complete, the molds were removed, allowing the remaining ribs to be steamed and fitted.

The Lugger is a big boat for solo rowing. The plans call for a second set of oarlocks forward. Two at the oars would comfortably keep the boat moving.

The hull could then be turned upside down to allow easier fairing of the outside, and over the next few days the hull was flipped several times so that the outside could be painted in the evenings while the interior fit-out progressed during the days.

Ten 1-1/8″-thick sapele floors (oak in the plans) were fitted, all with level top surfaces to allow them to double up as bearers for the larch floorboards which are in four sections for easy removal. The 2″ x 5/8″ oak seat risers support the 7/8″ painted sapele thwarts and bright-finished larch sternsheets. The timber for the latter was left over from a larch-clad barn Kate had built, so she used it instead of the cedar called for. The 2 -1/4″ x 1-1/8″ oak gunwale, tapered slightly at the ends, had to be steamed along the outside of the sheerstrake before fitting it to the inside. Kate decided to install a 3/4″ x 1″ rubrail at the sheer “for aesthetics and practical reasons,” adding to the protection provided by the 3/4″ x 7/8″ oak rubrail at the bottom of the sheerstrake specified in the plans.

The centerboard is made of 5/16″ galvanized mild steel and weighs 99 lbs, and is controlled by an uphaul with a 3:1 pulley system. The rudder blade—not shaped in the elongated ovoid designed by Paul, but more of what Kate thinks is a “traditional lugger shape” with straight leading and bottom edges—is in yellow cedar sheathed in ’glass and epoxy, rather than the more traditional bronze-pinned oak in the plans. The cheeks and tiller are oak.

Each of the main’s reefs shorten it by about 2′. The mizzen mast is set about 9″ to port to keep well clear of the tiller.

Kate clearly loves her boat, but she now realizes that her expectation that she would be able to launch and recover it easily singlehanded may have been unrealistic. At around 770 lbs, it is not a light boat, but as long as she can back the trailer far enough down the launch ramp to float the boat off the trailer, and with a bit of patience, perhaps she will be able to meet the challenge. When I met up with her, she had three of her fellow former students with her and we had no problem at all with rigging, launching, and recovery. The solid spruce main and mizzen masts are both easily stepped singlehandedly. The mizzen mast is offset to port by 9″ to allow the tiller a full range of movement.

Unladen and with centerboard and rudder blade raised (the latter is then just clear of the level of the bottom of the keel), the boat’s draft is about 8″. With the wind directly onshore, we decided, as soon as we had launched, to row out to a nearby vacant mooring to hoist the sails. As you would expect with a boat of this weight, it took a bit of effort to get it going with the oars, but once it had some way on it became much easier. Kate didn’t install rowlocks for the forward thwart, and so it was difficult to get the right fore-and-aft balance with two people in the boat.

The powerful balanced lug mainsail has an area of 122 sq ft and an 18′4″ leach. The 20 sq ft mizzen provides balance and gives the boat good manners when luffed.

The 122-sq-ft lug mainsail and 20-sq-ft Bermuda mizzen sail were also made as part of the BBA course but, as the photos show, the mainsail needs some tweaking to lose the crease from the throat to the clew. With two of us aboard, we had a most enjoyable sail in a good Force-3 breeze with flat water in the sheltered waters of the River Torridge in North Devon, England. We had plenty of room: in fact, there were seven on board on launch day at the Academy and it didn’t seem at all crowded. The boat has a wonderfully lively performance and is easy and responsive on the helm. On a beam reach, it averaged about 5.5 knots, although when two others took over, the wind got up a bit and it looked as if it was going a little faster at times. It tacked through about 90 degrees and carried way very easily through the eye of the wind. After cleating the mizzen, it is easy to tend the mainsheet while steering and, with no headsail, there isn’t much for anyone else to do except enjoy the ride. Kate need have no fears about sailing the boat by herself.

Twenty years seems a long time from the publication of plans to the completion of the first boat, but it is nice to think that other examples of this great little boat might now follow.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boatbuilding and repair industry, and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

16′ Centerboard Lugger Particulars

[table]

Length/16′

Beam/5′ 11″

Depth amidships/1′ 10″

Displacement/550 lbs

Sail area/142 sq ft

[/table]

Plans for the 16′ Centerboard Lugger, Design #124 are available in both print and digital format from Paul Gartside for $195.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Wow, what a beautiful sailboat! I’m planning on building an Arctic Tern this Winter, but would certainly take a close look at this yawl later. I think I’d probably install a Norwegian tiller though.