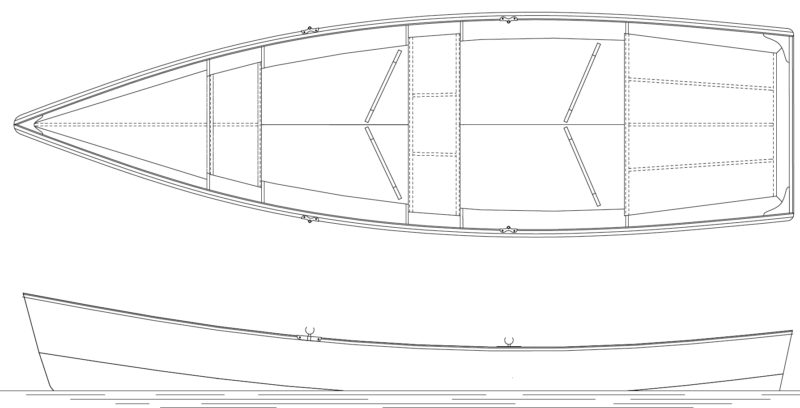

Flint is a 14′ 10″ open boat Ross Lillistone originally designed for Eddie Guy, who lived on an island in Moreton Bay, Australia, and traveled between the island and the mainland by rowboat. Eddie was disappointed with the boat he had been using and asked Ross to design one better suited to the task. The Flint is designed primarily as a rowboat, and moves quickly and easily under oars. It’s designed to track well even in a crosswind, to handle chop without pounding, and to handle longer voyages under the power of a small outboard. It has ample freeboard forward and a sharp, flared-V forefoot with more curvature than seems possible from plywood. The bottom fills out to a shallow V amidships and rises just enough aft to give the waterline the clean exit of a double-ender.

Flint was designed to reach displacement speed with ease, and it takes very little indeed to move it well: one pair of oars, the tiniest of outboards, or a small sail. Although it can exceed theoretical hull speed by at least a knot, it’s not designed to plane. Any outboard much more powerful than 2 hp would be overkill and would, in fact, throw the trim off and distort the waterline that normally makes it so effortless to drive. (After Lillistone received a number of requests for a boat along the lines of Flint but which could take advantage of more horsepower, he designed Fleet, similar to Flint in most respects, but with a fuller stern that can support a heavier outboard and readily rise to a plane.)

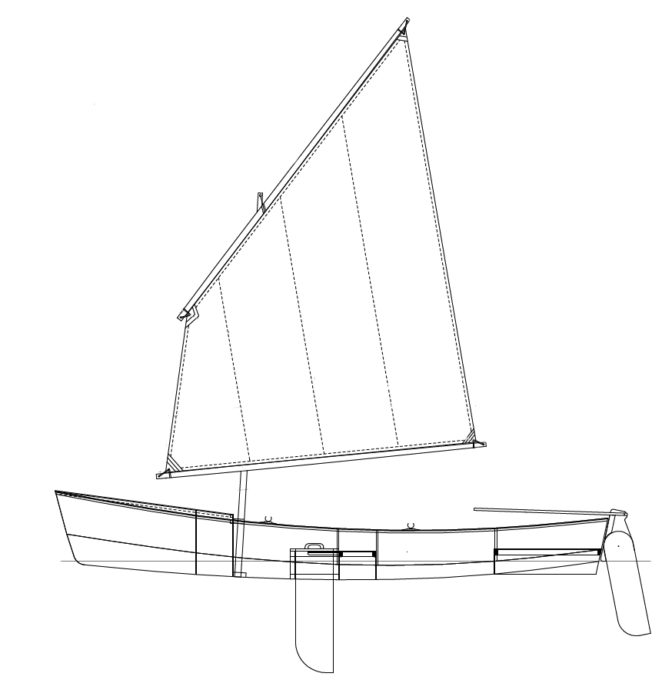

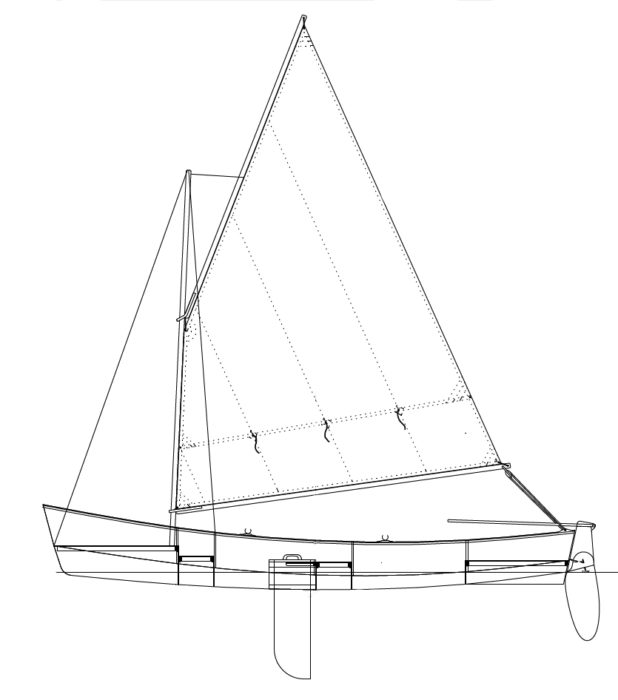

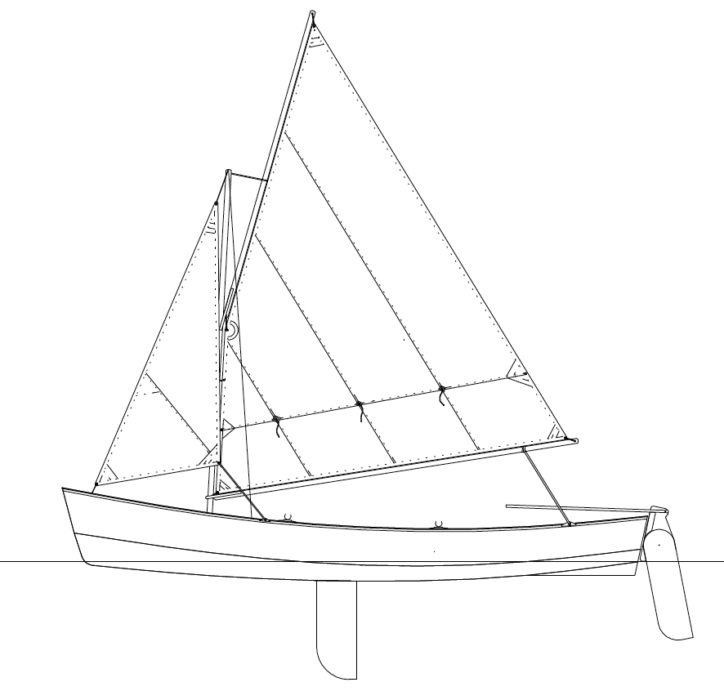

Some of Flint’s earlier builders experimented with a variety of sails, and the boat handled them so well that Ross returned to the drawing board and ultimately offered three sail rigs with the plans. The rigs include a 55.7-sq-ft balance lug, a 64.5-sq-ft gaff cat, and a gaff knockabout sloop with a 54-sq-ft main and a 10.5-sq-ft jib.

photographs and video by the author

photographs and video by the authorThe bottom panels have quite a bit of twist in them, but good marine plywood will take the strain and provide fair and symmetrical curves. Cable ties rather than copper wire held the panels together until epoxy bonded the joints.

It was Flint’s versatility that attracted me. Like many boaters, I wanted an “everything” boat that I could row, motor, or sail. I wanted to snorkel from the boat, explore the shallowest of inlets, and take camping trips with my wife and enough provisions for several days of crisscrossing the waterways between beaches. I also wanted to try my hand at fishing and so had that in mind when looking at plans. All that had to be in a safe boat that I could build myself, and would fit in my garage. Out of all the designs I looked at, Flint seemed most able to fit the bill.

Flint’s plans are available in either metric or imperial units and include all the drawings and specifications necessary to build the boat with or without the sailing option. The plans included dimensions for spars and sails for all three rigs, and plans for both 7′ and 7.5′ oars. The instructions are thorough and clear enough for a first-time builder like me. If a builder has questions, Lillistone is generally accessible via his website, his blog, or a Facebook group discussion page.

The boat is capable of carrying up to four people can be built as a rowing boat to weigh less than 100 lbs, light enough to cartop on midsize to larger vehicles.

The balance lug rig, carrying 55.7 sq ft of sail, is the most modest of the Flint sail plans. The gaff cat and the gaff sloop rigs both carry 64.5 sq ft.

I chose to build the balanced-lug version, which uses only one sail and an unstayed mast that can be stepped or unstepped in moments. This balanced-lug rig’s mast partner is designed as part of a foredeck and a bulkhead. This configuration eliminates the forward rowing station but the enclosed compartment increases the built-in flotation by another couple of hundred pounds. The configuration for the gaff rig has a forward rowing station and a lower buoyancy compartment.

Flint can be built without the sailing option using just four sheets of 1/4″ plywood and about 20 bd ft of dimensional lumber. Adding the sailing option requires a fifth sheet of plywood and another 15 bd ft of lumber for the spars. The construction method is stitch-and-glue and does not require a strongback. To get the correct curvature into the twist at the forefoot, the plywood should be marine-grade and high quality. For dimensional lumber I used Douglas-fir.

Pairs of the plywood sheets are scarfed together before drawing and cutting the side and bottom panels. Flint’s hull panels, main bulkheads, and transom went together more smoothly than I thought they would. I was concerned about that twist going into the plywood at the forefoot as planned, so much so that I waited until after that step to announce to family and friends that I was building a boat. But I followed Ross’s guidelines and instructions, and everything came together exactly as the instructions said it should. The pieces didn’t go together quickly, mind you. They required snugging down the cables ties a bit here, a bit over there, then a bit here again, methodically drawing the bulkheads down into the bottom panels to pry them apart and twist and creak that forefoot into shape. Stitching the boat together took hours with only me at the task, but it was a smooth and pleasing process. Seeing the boat rise out of two dimensions into three in a single day was extraordinarily satisfying.

Although I spent about 18 months of weekends building my Flint, other builders report having completed theirs in as little as two months. I used primarily hand tools; made my own oars, spars, belaying pins, rope-stropped blocks, and a jam cleat; and sewed up the sail from a Sailrite kit, all of which contributed significantly to my construction time.

Flint’s stability is about what I’d expected for a hard-chined lightweight boat with a displacement-type hull. If I’m the only significant weight on board, she’ll dip to whichever side I move to, gaining some stability once that side fully engages with the water. I’m familiar with this sort of motion, so it’s not disconcerting. When I put my 175 lbs fully onto a gunwale, the boat will ship water over that side, but it’s easy to move around in the boat as long as I keep a hand planted somewhere for balance.

The configuration for the balance lug rig, seen here, has one rowing station. The gaff rig configuration has a second forward rowing station forward and a low flotation tank instead of a foredeck.

The Flint has three watertight buoyancy compartments that, by my rough calculations, add somewhere around 400 lbs of positive flotation. In capsize drills with the sail in place, the Flint does not want to turn completely turtle. My Flint rides low enough on its side that the spars lie flat instead of driving tip-first beneath the water and allowing the boat to capsize further. During my capsize test, after I had the spars and sail flat on the water, I put my weight on the tip of the mainmast, and although that did push the yard and most of the mast beneath the water’s surface, the Flint still didn’t turn turtle.

It takes little effort to reenter after a capsize by rolling in sideways over the gunwale, and the cockpit does ship quite a bit of water with that reentry, but if you’ve gone overboard in a capsize, there will already be some water aboard. With only me aboard, I can swamp the Flint only so much and any water higher than the daggerboard trunk will flow out through the slot, leaving only about 3 cu ft to bail out. It can be completely swamped and still move under oars.

The Flint’s sharp entry keeps it moving smoothly through a chop and its skeg helps it hold a course in a crosswind.

Under oars I can do just under 3 knots at a sustained pace and almost 4 knots at peak effort. An experienced oarsman should easily be able to add another knot to each of those figures. I sometimes use a 30-lb-thrust trolling motor for auxiliary power, which pushes her at just over 3 knots. Ross reports a 2-hp outboard gets to 3 1/2 knots on idle and more than 6 knots using at about half-throttle with four people aboard.

The Flint can manage more power than the 32-lb thrust trolling motor shown here, and while a 2-hp outboard will push a loaded Flint around to 6 knots, the boat doesn’t have a flat run meant for planing.

The balanced lug rig is simple to sail and provides plenty of power. It’ll push the Flint at 4 or 5 knots easily, and I’ve had it surge up to 7 knots on a run single-reefed in 20-knot gusts. The boat points to within 50 degrees of the wind and sails well on all points, even when reefed. The helm stays almost perfectly balanced. When sailing close to the wind in stronger wind and chop, whoever’s on the main thwart will catch some spray, but she is otherwise a dry sailer.

I transport my Flint on a trailer, and launching and retrieval are easy, even when I’m by myself. When I’m setting it up for sailing it takes less than half an hour to rig the boat. It typically takes longer because the boat draws admirers wherever we go, and I get to chatting about her.

I’m extremely pleased with my Flint. It comes as close to an “everything” boat as I can imagine. Although it’s usually true that a jack-of-all-trades is the master of none, Flint seems to me to be an exception. It’s master of a couple and a praiseworthy jack of the rest.![]()

Roger Siebert is an editor in Austin, Texas. He rows and sails his Flint on local lakes, and recently trailered it to a few of his favorite places on the Florida coast. This was his first time building a boat.

Flint Particulars

[table]

Length/14′ 10″

Beam/4′ 3.25″

Draft, board up/6″

Draft, board down/35ʺ

Weight, rowing version/100 lbs, minimum

Weight, sailing version/150 lbs, minimum

[/table]

Balance lug

Gaff cat

Gaff sloop

Rowing version

Plans for the Flint are available from Ross Lillistone and Duckworks.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I am curious to know how it works out as a camp cruiser. Beautiful boat!

Thank you, Diane. So far we’ve taken the Flint on only one camping trip. It was for one night, and we didn’t sleep on the boat. We beached the boat and set up a tent, etc. The boat carried the two of us and everything we needed for camping just fine. We used to backpack a fair bit, so our camping gear is small and lightweight, which helped.

I understand why you prefer the cable ties to copper wire, but another alternative is to use soft iron wire instead. Advantages: the holes are smaller, and the wires are easily removed. Chesapeake Small Craft specifies copper wires, which you then force down into the seam before epoxying. I dislike this system, as it leaves a lumpy interior seam, while the wires have to be ground or sanded off on the outside. I seriously doubt if the remaining copper bits contribute anything at all to strength. I have used the iron wire system with several Pygmy kayaks I have built, and like it very much. The only difficult part is pulling the wires in the tight crevices at bow and stern. But a few seconds’ heat with a soldering iron solves that problem.

One time I had the epoxy cure in a seam that I later realized wasn’t quite flush. Turned out the only way I could correct that was to saw out the epoxy with a hacksaw blade (oscillating tool would have been great for that job) before I could nudge the panels into alignment. Which made me realize how strong the boat is with just the epoxy, even before glassing.

Were you able to stay within the weight specs? Billy Atkin used to point out that every “improvement” to make a boat stronger adds weight, even if it’s just an ounce here and there.

Anyhow, you have a nice looking boat that looks like it performs very well. Good job!

Thanks, Dave. My Flint weighs more than than the weight listed in the specs. Most of the extra weight is likely from adding inwales and covering the entire outside of the hull with fiberglass and four coats of a stout epoxy paint. I felt that the extra weight was worth it for how I plan to use the boat. I’ve already been dragging it onto and off beaches that have bits of shells and such waiting to gouge up a hull, and knowing that I have that protection has kept my mind at ease.

Great honest report. Thanks for that. You have a beautiful boat, well done.