In the autumn of 2011 Erik Schouw-Hansen and I were discussing our next adventure. In 2010 we had sailed together to the Shetlands—Erik crewed aboard my 31′ sloop on the first leg of a voyage from Norway to the Caribbean and back. We were both born and raised on the west coast of Norway, so for our next trip it was natural to look westward across the North Sea to the Shetland Islands. We wanted to try something new and settled upon rowing a small, open boat across the North Sea the following summer. We set mid-June the following year as our deadline to be ready for departure, and from that point we would wait for favorable weather conditions.

In Norway the faering is well known, and has proven its seaworthiness over many centuries. It was a natural choice for us, and we set our sights on finding one suitable for the crossing. After asking around, I heard about a newly built Sunnmørsfæring that would meet all our requirements. I called the owner, Leif Reidar Røv, and to our good fortune, he was enthusiastic about our adventure and was more than happy to lend us his boat.

Henrik Yksnøy

Henrik YksnøyIn the early spring we put a fresh coat of oil on the boat while preparing for the crossing. After we launched it, the seams tightened up as the wood swelled, but the boat still took on some water during the trip.

The faering was built by the boatbuilder Jakob Helset in Bjørkedalen, a small village on the northwest coast of Norway famous for boatbuilding. Hundreds of boats from faerings to replicas of Viking ships have been built here.

Leif’s faering is 17′ long and a bit fuller in the bow than most other faerings, but this suited us well, as our equipment list continuously grew longer and the space we needed grew larger. The keel was a bit deeper than those of traditional faerings, making it a better sailing boat, and adding a huge benefit: the ability to keep on a steady course while rowing in strong wind and big waves. The trade-off was that it wasn’t as good a boat for beach cruising, but we intended to launch, just once, in Norway, and land, just once, in the Shetland Islands.

We were off to a good start after finding the boat and bringing it back to my home in Volda, but there were a lot of things we needed to do over the winter. One of our most important preparations was to have covers made for the boat. They would be crucial in providing shelter and a measure of comfort on board. The cover at the stern would be a sleeping shelter. The cover over the bow would protect the gear and drinking water stowed there.

Erik Schouw-Hansen

Erik Schouw-HansenBefore departure, we tried to figure out where to store all our gear and how to distribute the weight. Here Henrik was checking the fit of the aft part of the boat where we slept during the crossing.

For our safety equipment, we brought a life raft, two satellite messengers, a handheld VHF, two survival suits, and flares. The range of the VHF would not be very far when while seated in a faering at sea level, so we would have to rely on meeting up with other vessels in transit to get updated weather forecasts.

We had to prepare ourselves as well, and spent many hours in the gym and swimming pool. During the spring, we also did some rowing in the faering. Our longest training trip lasted six hours, but six hours does not get you very far in the North Sea. It would have helped if we had rowed even more, but Erik lives in Bergen, a seven-and-a-half-hour drive from Volda, and he wasn’t able to spend many hours rowing with me in the faering before we left.

Henrik Yksnøy

Henrik YksnøyWhile the faering was docked at a marina in Henrik’s hometown of Volda, we rigged the tarp decks for the first time, and prepared the open boat for ocean rowing.

We weren’t the first to set out on this crossing in a faering. Ragnar Thorseth, a Norwegian adventurer, crossed the North Sea alone in a faering during the summer of 1969. Olav Lie Gundersen and Tommy Skeide repeated the feat in 2005 in a type of Norwegian faering called a geitbåt; then, after reaching Shetland, they continued the voyage and rowed all the way to the Faroe Islands.

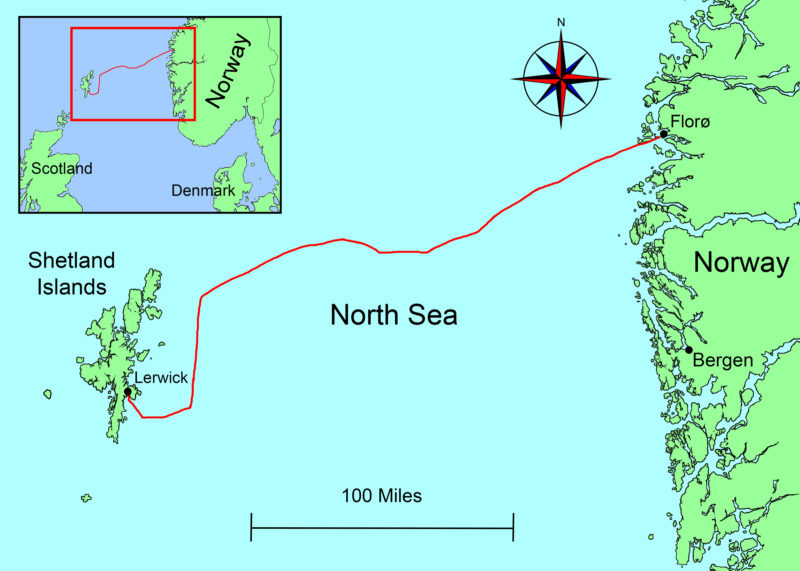

We did not have to wait long for our window of suitable weather. On the day we finished getting our gear collected and were ready to leave Volda, the weather report looked promising. We put the faering on a trailer, packed our things in it, and drove south to Florø, the most westerly town in Norway and the closest we could get to Shetland for our departure. The straight-line distance from Florø to Shetland is about 200 nautical miles. I am the optimistic one of us, so I guessed we’d make the crossing in four or five days; Erik put his money on ten days or more.

Erik Schouw-Hansen

Erik Schouw-HansenAt long last we were on the North Sea and heading to Shetland. It took a long time for the Norwegian coast to disappear below the horizon.

We were ready to launch at 4:00 am on Wednesday, June 20, 2012. We had been awake for 20 hours already, and I was tired and exhausted. We remembered most of the important things on our list, but managed to forget the tiller. I knew exactly where I had left it back home, but to drive seven hours home and seven hours back to pick it up was out of the question. From now on, every hour was valuable; we had no time to lose. We had to take this weather window, as it could easily be the only chance this summer.

We made a new tiller, improvised from a piece of wood and some pieces of thick steel wire we found in the harbor. It didn’t look as nice as the one we left behind, but it was functional.

We weren’t off to a great start, but the conditions were perfect. The seas were calm and there was a light breeze from east, just as forecast, and a light drizzle as well, but we only cared about the wind and the waves and hardly noticed the rain.

Erik Schouw-Hansen

Erik Schouw-HansenHenrik gave our cobbled-together tiller a try. It served our needs, as we didn’t steer actively, and kept the rudder in a fixed position to keep us on track. In an attempt to avoid tendonitis, I tried some wrist braces in the beginning of the trip, but after the burn on my wrist, I had to take them off.

We wanted to take full advantage of the good conditions, so we rowed together for 20 hours straight. I could hardly stay awake, and desperately needed some rest. To get a chance to sleep, we started rowing on shifts, six hours on and six hours off. The wind was picking up, still from the right direction, over our stern, and we were making good speed, on average, 10 nautical miles for every 6-hour shift. That put us on par with our best estimates. If we could maintain a pace of 40 nautical miles per day, we could make it to Shetland in only five days.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

It was a physically demanding task to close the distance to Shetland, but in spite of the hard work, neither of us had an appetite and we hardly managed to eat. It may be that the movement in the boat was making us a little seasick, and the exhaustion of rowing for hours on end made us long for sleep more than food. That first day we ate less than a meal, a few snacks, and a little chocolate.

Our meals were dehydrated and needed only boiling water to prepare them—simple enough, but a wave caught me off guard, and I poured hot water over my left wrist. It was a serious burn, and the only thing I could do to treat it was to reach over the side of the boat and hold my hand in the cold North Sea water. Our first-aid kit was well stocked but obviously had its deficiencies; some treatment for a burn would have been highly appreciated. After a while the pain subsided and I was back in the routine, rowing toward Shetland.

Erik Schouw-Hansen

Erik Schouw-HansenAll of our navigation was done with a handheld GPS. Here Henrik was using it to check our position and measure the distance left to Shetland. The gloves he was wearing were a crucial part of our outfitting.

We rowed through the night and in the dark passed the first offshore oil and gas platforms, our first milestone. This meant we were getting somewhere. We were definitely in the North Sea where there are quite a few platforms, and keeping the required distance away from them was at times proving to be difficult, as the wind was determining our course more than we were.

It was hard for me to motivate myself as we rowed away from the Norwegian coast. The high mountains followed us for days—they just wouldn’t disappear—and it seemed as though we made hardly any progress. That was one of the drawbacks of rowing rather than sailing—we were always looking backward. I had to remind myself to turn around occasionally and look over my shoulder to make sure the coast was clear. One time I turned my head and found an oil-rig supply vessel just a few hundred yards away. I hadn’t even heard it, and I didn’t think they noticed us until I called them on the VHF. In swells, fog, and rain, a faering is difficult to spot, and a small boat made of wood rarely shows on a ship’s radar.

On the second day, Erik had a visitor while he was rowing. A whale as long as the boat swam alongside us for a few seconds. Erik was shouting, both thrilled and frightened; I was in my sleeping bag and scrambled out as fast as I could to see what had raised the alarm. Erik doesn’t always get “port” and “starboard” correct, so I was looking in the wrong direction and just missed seeing the whale.

Henrik Yksnøy

Henrik YksnøyFor the first days of the trip, the sea was quite flat and made the rowing easy. Here the sun had just gone down, and Henrik was preparing for the night watch.

After a while, it became difficult to separate one day from another. We did most things without thinking, and we hardly spoke to each other. When we changed shifts, we talked briefly about the distance achieved, strength and direction of the wind, and not much more. We did not have much energy left for small talk. I had the graveyard shift, from midnight to 6 a.m. Even though it was summer and we rowed in high latitudes, it was quite dark during these hours. It was cold as well, but the rowing helped keeping me warm.

After three days of mild weather, the wind freshened and the waves grew larger; we needed to pay attention to the waves, making sure we took them from the right angle. The wind helped us make good speed, but it was not comfortable anymore. Back home, we wouldn’t have launched the faering in these conditions, but underway we didn’t have a choice. Fortunately, we were familiar with the boat by then and able to manage it through the rough water.

In the growing waves and generally cold and wet conditions, we got into our dry suits and would remain in them, for safety’s sake, for the rest of the crossing. They were not very comfortable to wear, and even worse to row in. Sealed up inside the suits day and night, we were perpetually clammy.

Henrik Yksnøy

Henrik YksnøyHalfway into the crossing, the wind had picked up and we needed to get into our survival suits.

After we crossed into the United Kingdom’s territorial waters, we rowed up close to a U.K. Coast Guard vessel. Over the VHF radio, they told us that we would have a few days of easterly winds, followed by a northerly gale. Erik and I calculated that we would reach Shetland before the weather took a turn for the worse.

Only 12 hours from the Shetland coast, Erik was rather cheerful when his rowing shift ended and he headed off to sleep that night. His high spirits surprised me because he is quite seldom so cheerful. During my watch, the wind picked up and I struggled to make progress. With the wind and the waves coming from the north, I had no choice but to turn the faering downwind in an attempt to ride out the gale. When Erik woke up, his good mood vanished when I told him we were still 12 hours out, headed due south parallel to the coast of Shetland, and not any closer than we had been when he went to sleep.

Erik Schouw-Hansen

Erik Schouw-HansenThe waves had picked up and made the rowing much harder for Henrik during his shift at the oars. Erik was sitting in the cabin, not yet able to sleep in the rough conditions.

Erik took his shift at the oars, and I lay under the tarp during my six hours off, hardly getting any sleep as there was a too much movement in the boat. There was no need for my sleeping bag, as we were still wearing our dry suits. When I looked out from under the tarp, I saw Erik struggling at the oars to the keep the faering headed downwind. Whenever the boat slipped away from him and veered into a broach, the cresting waves would break over the gunwales and pour into the boat.

The rudder helped keep the faering on track, but the new tiller was a bit short and difficult to reach from the rowing thwart. Although we didn’t use the rudder to steer the faering on the waves, we were be able to control the boat with the oars.

We had had water in the boat all along, but at this point we were carrying a couple hundred liters. As the boat got heavier, its handling changed and was more difficult to control, reacting more slowly to the oars and taking longer to get back on track. During our hours off we bailed, but our efforts hardly seemed to produce any results—there was still a lot of water sloshing in the bottom, and we needed to stop bailing and take some time off to rest.

Erik Schouw-Hansen

Erik Schouw-HansenErik took this self-portrait at sunrise. The quarters were quite close with the “cabin” in the stern right at his feet. Erik, who stands about 6’ 6” tall, struggled to find a place to lie down and stretch out after his rowing shifts were over.

When it came my turn to row, Erik and I had to switch positions. With the aft tarp up, there was only one seat free for rowing, and during the switch the faering was at the mercy of the waves. We had to make the move fast while reacting to every wave coming at us. The wind had picked up during Erik’s watch, and in his six-hour shift he had learned to deal with the waves. I had never rowed in waves like this, so it took some time to learn how to manage the oars and control the faering in these conditions.

The boat broached a couple of times, and more water came aboard. We were not pleased with the situation. Erik was not lying down to rest, but sat at the opening of the tarp, afraid of being under it in case we were to capsize. His fear, however, was no match for his exhaustion, and he didn’t sit there for long. He soon disappeared under the tarp, completely spent.

Erik Schouw-Hansen

Erik Schouw-HansenDuring the final stage to reach the coast of Shetland, we rowed together for 20 hours to avoid missing landfall. We had spent almost a week within the confines of the faering.

Erik took a new turn on the oars, and after 18 hours of our trying to control the boat in the gale, it was my watch again. I studied the GPS, and saw that we would soon pass the whole length of Shetland; the next landfall would be the Orkneys, Scotland, or England.

During my next watch, it felt like the wind didn’t have the same strength as it had only a few hours earlier. The waves didn’t break in the same way and they didn’t slam against the hull with the same strength. Still, it was not possible for me to turn the boat to put it on a course toward land. To prevent us from passing Shetland altogether, I pulled out our sea anchor and threw it over the side along with 50 yards of rope, and attached the line to the stern. The sea anchor made the movement in the boat more tolerable, and, according to the GPS, reduced our southward drift. That was very reassuring as we by this time had already passed the latitude of Shetland’s capitol city of Lerwick, situated about 18 miles to the north of the island’s southern extremity.

We been carried south by the wind for the previous 24 hours when it was Erik’s turn at the oars again. I woke him up and we discussed our strategy and next course of action. The wind had calmed even more, and we could clearly see the coast of Shetland for the first time. Sighting land gave us some necessary motivation. This was our chance to reach the coast.

Henrik Yksnøy

Henrik YksnøyThe sea had calmed and Shetland as within sight, but there were still hours of rowing left.

We took down the aft tarp; no one would sleep now until we reached the shore. We pulled out the second set of oars, and rowed together. There were still swells from the north, making the rowing a struggle. We rowed for 30 minutes, then took a five-minute break. It was a pleasure to get off the thwart for five minutes, but even more painful to get back up on it. We had seat pads on the thwarts, but they didn’t help much anymore. I constantly had to change my position. I was so tired that Erik often caught me just dipping my oars in the water.

We were terrified at the thought of the wind picking up again and blowing us farther away from the island. Luckily, the wind was slowly dying until it suddenly went completely calm. In the still air, we could see more and more details of the coast. After a few more hours of rowing, we managed to distinguish the small island Bressay from the mainland, and we knew that Lerwick was not far away.

We took our last five-minute break just outside the guest harbor in Lerwick, and I was relieved, satisfied, proud, and completely exhausted. We arrived at the dock at 3:00 a.m., having been on the North Sea for six days and 23 hours. The final stage, where we rowed together, had lasted for 20 hours.

We made the faering fast and when we stood up, we struggled to stay on our feet, and had to sit down on the dock to keep from losing our balance. The pub had just closed—just as well for us—but some fellow Norwegians coming from the pub found us and took us aboard their sailboat. After a short celebration, we got the sleep we had longed for.

Erik Schouw-Hansen

Erik Schouw-HansenIn the harbor at Lerwick, Henrik took a last look at the faering aboard the Norwegian topsail ketch SVANHILD. We spent a few days in Lerwick while SVANHILD took our boat back to Florø.

We spent a few days in Lerwick, and had no plans for the return to Norway, either for us or for the boat. Our only goal had been to get to Shetland. But it didn’t take us long to cross paths with the captain of SVANHILD, an old galleon from Florø, the same town where we started our voyage. Luckily for us, the captain was happy to bring the faering home to Norway.

We spent some great days in Lerwick, enjoying the Shetlanders’ hospitality—especially that of Charlie Hunter who took us into his home, where we got everything we needed to recover from the voyage.

A few days later, Erik and I took the ferry to Scotland and flew home across the North Sea. Looking out of the window and down on the ocean, I was happy to be flying.![]()

Henrik Yksnøy was born in 1987 in Volda, Norway, and grew up on and by the sea. His home is surrounded by mountains and hikes the high country year-round. His interests include hunting, fishing, sailing, and kayaking. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Economics and Administration, and a master’s in Supply Chain Management from Norway’s Molde University College. Henrik works as Senior Associate in a business consulting firm.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Years ago, we visited the Norsk Sjøfartsmuseum [Norwegian Seafaring Museum, now known as the Norsk Maritimt Museum, or Norwegian Maritime Museum] in Oslo, and saw on display a rather unobtrusive faering, black with tar, honoring two Norwegians during WW II in German-occupied Norway. They had rowed this faering to the Shetlands to escape the occupation and to join the overseas Norwegian Resistance (if memory serves me right), or at least to join the fight against the German occupation. They were blown in a circle by a gale. I’m not sure how they navigated, probably by compass. And here these two young fellows have done it again! Henrik’s exciting, well-written article fleshes out what the dry museum card describing that long-ago trip couldn’t, for what nevertheless was an amazing exhibit. Thank you for a wonderful story!

What a great saga and a tribute to youth. Thanks so much for sharing. We built an Iain Oughtred designed 16.5′ faering. It is pleasure to row and sail. Rowing this boat across the North Sea truly staggers my mind. As both my boatbuilding friend and I are at an age when we do not want to go into the water we have installed two outer inflatable 7′ sponsons that fit under the gunnel. They have saved us twice during some heavy sailing. Can you send some more information on your Faering design?

JL: Can you tell or show us more about your inflatable sponsons? I have a 14′ sailing Whitehall and have thought of mounting something similar and would love to learn more about yours.

Seriously epic trip. Thanks for writing about it!

Henrik, an amazing adventure, well related! Thanks for sharing your story. Knowing what you know now, would you have deployed the sea anchor when the storm first started blowing you off course? It sounds like it might have saved you exhausting effort, provided a more comfortable situation in the storm, and lost you less ground, but I don’t want to take the wrong lesson from your experience if there’s something I’m missing.

Hi Dan,

Sorry for my late response. I experienced that when using the sea anchor, the stern is not always facing the wind and the waves all the time, as the boat have a tendency to turn sideways occasionally. And due to the conditions, we preferred to control the boat ourselves. I am not sure why the boat behaves like this when using sea anchor, but I suspect that we did not have a long enough rope attached to the sea anchor.

Love this article, with the boat being original, lovely lines. I have just built from scratch an Aylse skiff with the purpose of rowing across the North Atlantic from New York to Scotland, which I have also modified for this venture next May.

(Re Duncan Hutchinson) You made it! https://www.energyvoice.com/other-news/197650/oil-worker-completes-atlantic-rowing-journey-in-wake-of-rescue/

Thank you. Inspiring.

What a story! Well, as a fellow Norwegian (half Norwegian, with my childhood spent in Molde on the west coast of Norway), I’m very proud of what you have achieved. I sometimes dream of paddling from Lerwick on the Shetland Islands to Molde as tribute to Dad, but, as a 77-year-old, it maybe a little late!

Thanks for sharing this. Really inspirational.