A little learning is a dangerous thing

That’s according to a poem Alexander Pope wrote more than 300 years before Dennis Ward of Riviera Beach, Florida, figured it out for himself. Reading a book on stitch-and-glue boatbuilding inspired him to design and build a boat in 2004 even though he had no experience with either skill.

Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts

Dennis’s muse was Sam Devlin and his temptation was the boatbuilding method detailed in Sam’s book, Devlin’s Boat Building. After reading the book, Dennis went straight to work to create a boat of his own: “I sketched a dinghy on paper, then glued some pieces of wood together with epoxy, and was amazed I had made a boat that didn’t sink.” Cutting out pieces of plywood, drilling a bunch of holes, and wiring and gluing the pieces together just happens to be the easy part, but the goal is more than just keeping the water out. Dennis quickly discovered that the dinghy was unsafe on the water. Pope expressed that awakening of a novice to what has yet to be learned:

But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise

New distant scenes of endless science rise!

The subtitle of Devlin’s Boat Building is “How to build any boat the stitch-and-glue way”. Sam likely intended “any boat” to encompass the sizes and types the system works for—he has designed and built boats ranging from a 6′3″ dinghy to a 45′ motor cruiser—but “any boat” could also be taken to mean good boats as well as bad boats. Sam’s boats, the result of a wealth of education and experience in boat design and construction, belong in the former category. Dennis admitted that his boat had fallen into the latter: “That dinghy has since become yard art.” The lesson he learned was “Let the professionals design the boat!”

Photographs by and courtesy of Dennis Ward

Photographs by and courtesy of Dennis WardIn October of 2021, Dennis retired after a 35-year career as a Palm Beach County ocean lifeguard, rower, rescue-boat driver at Jupiter Inlet, Boynton Inlet, and Boca Raton Inlet. A couple weeks later, he got all six of his boats in the water for some photos. At the water’s edge, from left: Dennis’s self-designed dinghy, kid’s rowboat from a thrift store, Passagemaker Dinghy, Gloucester Gull, and Ben Garvey. The Gloucester Rocker is safely away from the water. His Chester Yawl isn’t shown.

Despite the disappointing results of his first efforts, Dennis thoroughly enjoyed the time he spent building the dinghy. For his second boat, he skipped the designing and bought a kit for Chesapeake Light Craft’s 11′ 7″ take-apart Passagemaker Dinghy. He finished it in 2007 and, although it had all the characteristics that would put it in the “good boat” category, the Passagemaker was only afloat a few times before Dennis was back in his back yard under a 10′ by 20′ canopy, “making more sawdust.” His series continued with a Gloucester Gull and a partially built child’s rowboat he bought in a thrift store for $30. The Gull was afloat only a few times, and the little rowboat has yet to be launched and is waiting for an interested kid he can give it to.

The mild weather in Florida made it practical for Dennis to build the garvey outdoors under a canopy.

One of Dennis’s friends bought plans for Doug Hylan’s Ben Garvey, decided the project was more than he could manage, and gave the plans to Dennis, who started building it in 2011. After he had finished the hull and flipped it right-side up to begin work on the accommodations, he decided to do away with the center thwart. “That way I wouldn’t be stepping over it, and there’d be 8′ of space on the bottom for horizontal activities, like napping.”

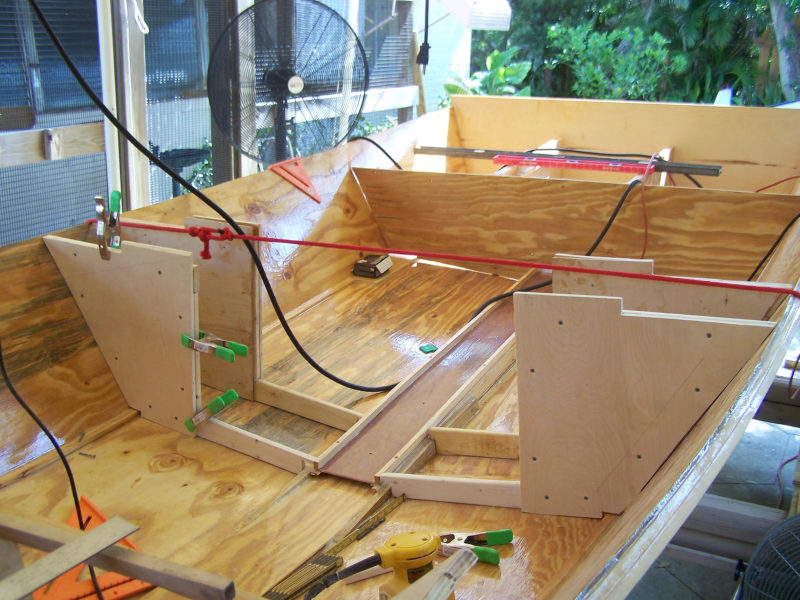

Having decided to omit the center thwart to open up the center, Dennis devised a structure that provided a walk-through passage between partial side benches and framing across the bottom.

A cockpit sole over the added interior framing provides a smooth surface for napping and enclosed spaces for flotation.

Concerned about losing the strength the thwart would have provided to the hull, he replaced it with two enclosed storage-compartment seats on either side. “I also intended to add several more frames on the bottom to add more strength to the chines and sides. The extra frames would be a tripping hazard and make napping uncomfortable; adding a cockpit sole on top of the frames seemed to be the ideal solution. I ended up with a double-hulled boat with flotation in between.”

The gunwales are teak and were initially varnished but Dennis decided “it’s like lipstick on a pig. This is basically a workboat, not a fancy piece of furniture.” He also embedded tie-dyed fabric on a pane forward and a hatch aft “because I wanted to learn how to do that. What I didn’t know at the time is that I coulda bought clear epoxy, instead of regular yellowish epoxy. So the tie-dyed bright whites turned yellow.”

Dennis finished building the garvey in 2012 but then left it on sawhorses under a canopy for several years until he could afford a trailer. A few more years drifted by as he saved enough for a 25-hp outboard for it.

Dennis worried that his weight in the stern along with that of the motor and fuel tank would cause the bow to rise too high, but It sat in the water perfectly.

While the garvey waited, Dennis’s mother gave him the plans for the Gloucester Rocker as a Christmas present. That was in 2017, and all through the following year he worked on it without telling her. The hull and rockers were straightforward work but the seat and grab bar—fashioned from walnut and holly that he had harvested on his mother’s lot—were not. The curved and beveled joints were not easy to get right and by the time he got perfect fits, the two pieces had taken more time than the rest of the boat. The next Christmas he surprised his mother with the rocker; she was delighted with it and she uses it to hold her dog’s toys.

Rob Rogerson

Rob RogersonOn the boat’s first sea trial, Dennis was “somewhat surprised how powerful the 25hp motor was. The garvey is a heavy boat but it got up on plane right away and I wasn’t comfortable going any faster than half throttle. An hour later, the garvey was back under the canopy.”

The garvey was finally ready to launch in 2020, but it wasn’t launched until this year for what Dennis says are “various lame reasons. Mostly, I’d rather build boats than go boating.”

Dennis’s 15′ Chester Yawl kit boat is being built with the help of his 86-year-old mother. She offered her basement for the project.

And he has been building boats. A Chester Yawl is in the works in his mother’s basement in North Carolina. Earlier this year, Dennis built the molds and a ladder frame for the L. Francis Herreshoff pram featured in John Gardner’s Building Classic Small Craft. The hull of the 10-footer is usually built in lapstrake cedar on steam-bent white-oak frames, but Dennis had been given a generous assortment of sapele strips and was eager to turn them into a boat.

In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts

Strip-building would be uncharted waters for him and, more cautious now after the experience of his first dinghy, he floated the idea of strip-planking the pram on the WoodenBoat Forum. He was dissuaded from making an attempt that could waste time, money, and valuable wood.

New distant scenes of endless science rise!

Rather than forge ahead, he bought Nick Schade’s book, Building Strip-Planked Boats. “I’ll read up some more before I decide what to do.”

Dennis is happier building boats than using them: “The prominent pleasure of wooden boats is in all the different things I learn in the building process.”

Do you have a boat with an interesting story? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share it with other Small Boats Magazine readers.

I understand completely Dennis’s preference for building boats. With a career in the military, I built boats in Nebraska, Panama, Alabama, Virginia, New York, and Colorado. Each was self-designed for local conditions. Sizes have varied from 14′ to 20′, for paddles, oars, sails, and full-planning power. Woodworking experience and an engineering degree have helped.

Being now retired, I have built five boats in Colorado, and the next build (#11) is underway. I only possess four boats currently. Others have been sold or given away, and one of the current boats will be donated to a charity auction.

See my work at developable-surface-boat-designs.blogspot.com

I recently finished boat #13, a kayak (#12 was also a kayak). Yesterday, I bought a used trailer which I will modify to carry our two kayaks. I sold two boats recently and have five more at home of which I am advertising one for sale. A potential buyer called me from California; told me I am underpricing the boat, but I explained that Colorado is a boating desert, not many buyers here.

I have no desire to build a boat from someone’s kit. Each of my builds is an original creative expression. I could build furniture for a much larger market, but that doesn’t inspire me. Designing the curved functional structure of a boat is an enjoyable challenge.

I am the opposite, I like wooden boats but I would much rather sail than build! It is interesting to me that America is awash with plans and kits but not many builders to put the kits together. The only builders I see advertising are high-end custom builders, far afield from those who would be interested in a kit build. I wonder if there would be more wooden boats around if those who like to build them were willing to put their services out there for hire.

Andrew, unfortunately there are a lot of official rules, regulations, and liabilities if you build boats professionally for others. If you build it for yourself, not so much. Hence I think that most of us who enjoy building boats prefer to do it out of enjoyment rather than for profit.

Bill

I don’t have in mind someone running a a fulltime business. More like a subsidized hobby–if you have in mind to build another boat, why not have me pay for the kit and materials and a bit for your time.

I’d be curious if you have specifics on the official rules, regulations, and liabilities, because I don’t know of any in the situation I have in mind. My state has pretty much eliminated products liability so maybe it’s different elsewhere.

William, my above comment may have sounded a bit aggressive. If so I apologize. My overall point is this. The last two decades have seen an enormous growth in the quantity and quality of small wooden boat designs and many kits for home builders. I have personally spend time on the internet looking for a builder who would be willing to build a kit for me and have found no one. The options seem to be to pay $40,000 to $60,000 for a custom build by a professional boat building company (to get, honestly, something too pretty for me to want to use) or to scour the used market. It seems to me that if someone wanted to build, say, 2 Caledonia Yawls a year there would be interested buyers. At the very least the builder wouldn’t have his or her spouse looking askance at the checkbook!

No offense intended, Andrew, but the builder you seek probably doesn’t exist. There is a huge difference in doing a project for one’s own desires and doing a project to satisfy another’s desires, and more importantly, their expectations. The self builder, such as the author, can walk away at any point. But may not be able to if building another’s boat.

Andrew,

I am a Seattle-based shipwright who builds small boats for people on occasion (including a kit boat right now). What do you reckon would be a fair price for a Caledonia Yawl, ball-parking: 400-500 hours for that build, several thousand for materials/rigging and outfitting, supplies, business overhead (shop space, insurances, licensing, tooling, etc.)…? Realistically, there aren’t many people who can afford to have that built, nor many people who can afford to build that for people. I have tried for several years to figure out how to make the numbers work for small craft, and I just haven’t figured out how to do it. It’s a tough way to make a living.

I am with you- there should be more builders of small boats out there. Surely it can be done, especially when talking about a production operation, where several of the same boat will be built. But I think that’s why we see a lot of kits and plans, and not many builders.

John Bishop, I think you’ve hit the nail on the head. I look at what people pay for similar production boats: Norseboat 17 at $26,000, Melonseed at $15,500, and Gig Harbor Salish Voyager at $17,495. I’ve seen good quality used Caledonia Yawls for around $19,000. I bet even paying minimum wage for the time spent would yield very low margins at those prices?

This is an interesting perspective on building versus boating. Great to have the choice.

I have build only two boats until now, a Kymi River canoe and a NE Dory. After the dory was finished, I found myself looking for the next project, a GIS perhaps? Or a CLC Peapod? I resisted. Now I’m concentrating on using the boat: sailing, rowing, paddling. And I modify it according to my needs and my growing user experience. Building boats as end in itself seems not the right way to me.

Great article. I understand the “addiction”!

Boat number 17 came out of the shop a year ago. I’ve also built three of the Gloucester Rocker boats, which were fun as well as challenging, at times, projects.

I, too am a serial builder. I generally try them out, then sell. I can always recover my direct costs, and I joke to my friends that I often make nearly 50 cents an hour. Beyond the economic challenges, when you hang out a shingle, your customer is going to ask you to build “one of these”, finished by May. I build boats that speak to me, challenge me, or otherwise get my attention. I finish when I get around to it. I wouldn’t have it any other way. I can’t begin to imagine the plug and chug of kit assembly for less than I could make flipping burgers.

Seems that I also prefer building them to sailing them. So far, a Lunenburg dory, a Greenland skin-on-frame kayak, an Acorn Auk, and I restored an 18″ canvas/cedar canoe. I have five more in the planning/dreaming stages. ‘Tis fun, learning new ways of putting them together.