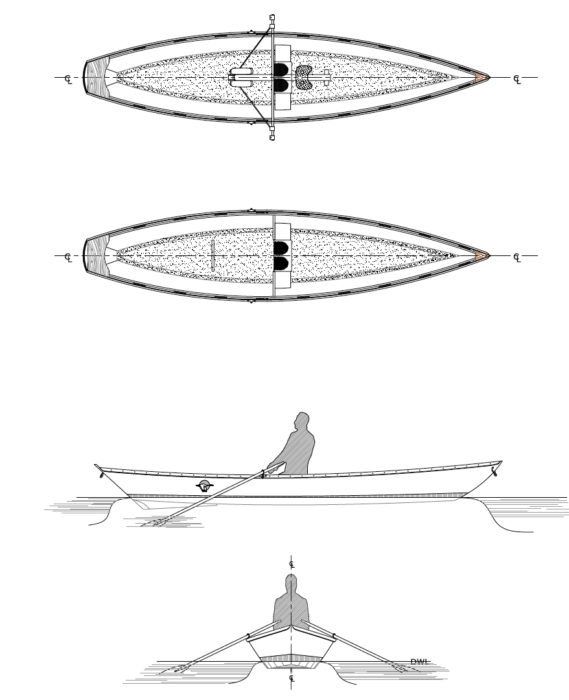

At Cathedral Park in Portland, Oregon, the Willamette River was flowing gently, leaving barely discernible eddies around submerged pilings a few yards from the beach. Skamakowa was 75 miles downstream, and I had five days to get there, relying on the current and a pair of oars. My boat, named MAC after my father, is the first of the four dories I’ve built. A narrower and more elegant version of a traditional Gloucester working dory, MAC is outfitted with a drop-in sliding seat and outriggers. As I swung into the Willamette’s current under the long shadow of St. Johns Bridge, I pulled hard to get away from diesel and car exhaust, ski boats, and boom boxes, and headed to the other side of the river looking for the southern entrance to Multnomah Channel.

Barely 1/4 mile downstream I rowed past a line of berthed tugboats, and a deckhand on one watched me glide by. I hollered, “How far is Multnomah Channel, and where I can buy food once I’m on it?” He yelled back, “Two-and-a-half miles, make the turn, you’ll see Fred’s Marina!” I gave him a thumbs-up and then kept a steady cadence close to shore as yachts, ski boats, and fishing boats motored midchannel into Portland proper at the end of a warm weekend.

Sliding-seat rowing efficiently transfers my energy to the oars and keeps me moving and flexible. I tried kayaking, but my back couldn’t tolerate the sitting position: My legs went numb. The rear-view bicycle mirror clipped to the visor of my hat is my front-view mirror for rowing.

The usual afternoon northwesterly was in a kerfuffle with the river, and I rowed into a mild chop. In the bicycle mirror clipped on the bill of my baseball cap, I saw the entrance to Multnomah Channel begin to widen; over my transom the white summit of Mount Hood stood sentinel over the Cascade Range. Floating homes were packed along a mile and a quarter of the mainland shore of the channel, with Fred’s Marina anchoring the neighborhood’s southern end. The store had pints of milk, a dizzying array of sodas, coolers full of beer, smokie sticks, jerky, chips, cookies, V-belts, fuel filters, and gas. No fruit or veggies. I bought a package of jerky and a bottle of water and left, rowing past houseboat after houseboat, most with docks for porches, kayaks stored next to lounge chairs and ski, sail, and cruising boats tied alongside.

The concrete fixtures of some pipes used for flood control on Sauvie Island create a harbor just the right size for MAC.

A muscle boat blasted heavy-metal music, and I was eager to get to the farmlands and forests beyond this clutter of pleasure boaters still reveling in the weekend’s last hours. Although this was a no-wake zone, few boaters seemed not to know or care about that, and I hoped I would encounter less traffic farther up the channel. After an hour and a half of gliding northwesterly, the channel turned north into a lee and the water turned silky flat. I searched for someplace to eat, and asked a teenager hand-lining from a dock if there was a restaurant up the channel. He said “Yes, Mark’s, about 4 miles.” It was two hours to sunset, and I had another hour of rowing to get to the restaurant. Soon I smelled food coming from a kitchen, still a mile ahead. Mark’s turned out to be a floating restaurant in the middle of a neighborhood of floating homes, and the food was better than I hoped for—made from scratch with organic produce from the local farms. The advice was good, too: The staff warned me of pile dikes, submerged pilings, and the sudden opposing currents at the confluence of Multnomah Channel and the Columbia. The most valuable information was about the marine park on Coon Island, 5 miles downstream: The mosquitoes there were very bad. That wasn’t good news, for I sometimes have allergic reactions to mosquito bites. And besides, I didn’t relish being trapped in my tent listening to the incessant hum of flying bugs wanting a taste of me. I needed to camp where there was a breeze.

Fatigue set in as I got back aboard MAC. I had been on the water since five a.m., had traveled 23 miles, and needed to find a campsite soon. (I’d begun the day escorting a friend on the Bridge Swim on the Willamette, an 11-mile swimming endurance event through the heart of Portland.) The sun would set in an hour. Two standup paddleboarders quietly glided past me in sharp contrast to the floating party I’d experienced at the outset. The weekend was settling down, and despite my exhaustion, my hopes for serenity on the river rose.

Fatigue set in as I got back aboard MAC. I had been on the water since five a.m., had traveled 23 miles, and needed to find a campsite soon. (I’d begun the day escorting a friend on the Bridge Swim on the Willamette, an 11-mile swimming endurance event through the heart of Portland.) The sun would set in an hour. Two standup paddleboarders quietly glided past me in sharp contrast to the floating party I’d experienced at the outset. The weekend was settling down, and despite my exhaustion, my hopes for serenity on the river rose.

The last three miles of Multnomah Channel offer quiet and solitude between wooded banks. Beyond the paper mill in the distance lies the Columbia River.

The dogleg in the channel ahead promised a gentle evening breeze on its northerly stretches, and as soon as the channel turned north, I found my campsite just out of view of a nearby farmhouse. MAC’s bow nosed into a flat muddy shingle, and I pulled on my rubber boots and carried dry bags to a grassy flat area. The tide would rise overnight, but I wasn’t sure how much, so I trailed a line from MAC to the tent. I’d sleep with it tied to my wrist. If MAC floated and drifted, I’d know it. I zipped the tent’s mosquito netting door down snug to the rope and, finally, stretched out to sleep. In the darkness, distant thunder rumbled while a gentle rain sharpened the smells of grass and earth.

A bend in the river surrounded by farmland and forests provided me a place to camp. With little current and minor tides in the Mutlnomah Channel I could leave MAC overnight only slightly aground. A line from her bow to my wrist as I slept was all I needed to assure me that she’d not leave without me.

I slept soundly and woke at 5 a.m., checking the weather forecast on my VHF with the volume very low to keep from betraying my presence. After spending 45 minutes quietly repacking and stowing gear, I pushed off and floated along on flat water with a gray ceiling above. As I leisurely ate granola and nuts that I’d soaked overnight in a ziplock bag with water and some powdered milk, cows slowly made their way along the roadway up on the bank. I had about another 10 miles—a little over two hours of rowing on the ebb—to reach the town of St. Helens and the possibility of a hot meal.

A river tug pushed a gravel barge by me. I rowed through the right-angle bends in the channel, and for long stretches silence surrounded me except for the rhythmic sound of rowing, the lowing of cows, and the chip-chip call of ospreys. On this stretch of the channel were the remnants of a fishing industry that fueled growth in this region until 40 years ago: Ships rusted in disuse, some sank in place. Rotting stumps of pilings with bushy green tops of volunteer grasses slid aft. An osprey hovered over the water in the distance. For almost three hours, I took in the pastoral quiet of the channel, watching the busyness of birds while the oar blades drifted aft and the current gently carried me downstream.

Ospreys, like this female in a nest on top of a dolphin by a paper mill, are often mistaken for immature eagles but adult osprey are two-thirds the size of bald eagles and have half the wingspan. Still, it’s impressive to see an osprey hover fifty feet above the water, fold its wings, plummet, and dive as much as three feet into the water, then emerge with a fish in its talons.

As I passed a paper mill an osprey with brown wing tops, gleaming white chest, underwings, and crown alit on its nest on top of a mooring dolphin. Fledglings tested their wings, flapping furiously while their talons gripped the edges of the large nest. As I rowed toward the base of the dolphin, the adult female osprey loudly admonished me with a sharp, descending skreeee. Forty years ago, DDT had driven ospreys to the brink of extinction. Now their nests are on the top of practically every mooring dolphin and navigation marker. The Army Corps of Engineers has accommodated the osprey by constructing nest platforms away from lights and markers on the Columbia River.

Pile dikes extend from both sides the Columbia’s shoreline. A “king” pile, the tall bundle of piles, marks the end of the pile dike for better visibility. These dikes are meant to keep the river banks from eroding and sediment from settling in the channel. Some argue that they do just the opposite. Either way they can cause small craft a lot of grief if trapped against them by the current. The river current during an ebb can exceed five knots and on many of the older pile dikes that kind of hydraulic scouring action wears each pile in a dike thin and the flow can pull floating objects against the dike. I avoided all of them.

The northern tip of Sauvie Island finally slipped by to starboard where Multnomah Channel flows into the Columbia. Off my port bow an 80-yard-long pile dike angled out from the St. Helens shoreline, forcing me into the middle of the river and closer to another dike, one extending 450 yards from Sand Island. In the ¼-mile-wide gap between the dikes, the current suddenly accelerated away from the marina entrance. I struggled to round the tall king pile and had to pull hard to get to the St. Helens marina.

At the long dock paralleling the river I secured MAC and walked up the ramp and into town. It was just 11 a.m., and I had to wait half an hour for the restaurants to open. After lunch, and feeling recharged, I ambled back to MAC. Mount St. Helens, the volcano that erupted in a 1980, was visible to the northeast.

When I rowed out into the Columbia, MAC began to drift upriver. I had dawdled through the late-morning slack tide and now I’d have to work against the flood, pulling down the river channel past sandy beaches and private and commercial docks. Three quarters of an hour later I pulled MAC onto the sandy north end of Goat Island to have a cup of tea and rest for a few hours. Anticipating a breeze, I set up my tent, curled up on my sleeping pad in front of it, and fell fast asleep.

Cargo ships crossed paths in mid channel while I rested on Goat Island. I am always awed by how ships as large as Panamax freighters can navigate so close to the shoreline as they cut their wakes upriver and down. With such close quarters on the river I use a smart-phone app to keep tabs on river traffic while I’m underway.

When I awoke, an otter at the water’s edge was staring at me. I lifted myself onto my elbow, and it ducked into the water and swam upstream along the shoreline. I lumbered up and checked MAC to see if anything had been chewed up by the otter. All was in order. I went back to my camp stove for a wake-up cup of tea while watching two freighters approach from opposite directions. Safe on the island, I opened the marine traffic app on my smartphone to get the names of the ships. This app has proven quite useful for checking on river traffic. Before I had it, I would call Vessel Traffic Services (VTS) on my VHF ship traffic advisories; now I can simply look at my phone to avoid the big boats headed my way.

The wind had increased while I slept, so I dragged my tent higher on the beach and waited for the wind to abate before heading to Kalama, a protected boat basin about 5 miles downriver. It was dark when I set out in a mild breeze. I checked my phone for river traffic, and found no ships in my area. I switched on MAC’s running lights, scanned the river for fishing and pleasure boats that wouldn’t shown on the app, and then pulled hard for 10 minutes to get to the Washington side. Then I turned downstream to Kalama. I rowed past a line of seven grain-elevator silos so brightly lit they ruined my night vision. Two miles farther downriver was the entrance to the Kalama marina. To my dismay, a freeway and a railway blocked me from town. It was almost 10 p.m., and I fretted about having to sleep on the dock. A security officer patrolling the boat basin got out of his car and asked me what I was doing. Upon hearing my plight, he called a motel, drove me to it, and said he’d keep an eye on MAC. I trusted him; he was the retired Chief of Police of Kalama, after all.

In the morning, after a shower and large breakfast, I called for a cab. Back at the marina MAC was right where I left her with everything intact, and in just 10 minutes I was back on the river. In the daylight I got a good look at Kalama and admonished myself for not checking access on my phone before stopping there. Its waterfront is industrial, and the marina is the only riverside accommodation for pleasure craft. There is a pedestrian bridge over the railway to an underpass under the freeway to get to town, but it’s a half-mile walk to get to it, and another half mile to the only motel in town. However, I could have made camp on Sandy Island, a 1½-mile-long wooded island directly across from the marina.

The morning was overcast as I rowed away from the noise of the freeway on the Washington side and pulled past Trojan, once the site of a nuclear power plant. Its 500’-tall cooling tower was an Oregon landmark until it was spectacularly brought down with an implosion in 2006. Heading northwest toward the Cowlitz River’s confluence with the Columbia at Longview, I stayed in the river rather than endure the noise of the freeway and railway along Carrolls Channel on the other side of Cottonwood Island. While following the 3-mile-long inside curve of the island, I felt a slight drizzle and pulled on my rowing jacket and snugged down my rowing cap. High slack at the confluence was still a couple of hours away. Longview was hidden behind Cottonwood Island, but I could see the steel lattice of the 1½-mile-long Lewis and Clark Bridge arching high over the Columbia. As I drew closer to the entrance to the mouth of the Cowlitz River, I began to feel the gathering countercurrent close to the island. The flood tide was still slowing the flow of the rivers, although not for long. I was apprehensive about the strength of the two rivers coming together.

At the north end of Cottonwood I pulled hard around the tip against the current and worked my way upstream 1/4 mile into the Cowlitz. There were several sportfishing boats anchored along the river’s ½-mile-wide mouth. I got my camera out to take pictures and let the current carry me out to the Columbia. While looking through the viewfinder, I heard a loud “Heads up!” I was drifting between a fisherman’s anchored boat and his fishing line. I lunged to the bow, lifted the fishing line over my running lights, an oarlock, my head and the stern light, and fended off the fisherman’s bow with my foot. Drifting away in the 5-knot current I apologized to the fisherman. Feeling foolish, I scurried into the Columbia and pointed MAC’s bow toward the gray fog downstream.

Green Point on the Oregon side of the river is appropriately named. It’s an expanse of granite wall covered with moss and topped with tenacious trees.

I moved quickly along the 5 miles of Longview’s working waterfront: gantries, conveyors, and cranes for containers, steel, lumber, logs, pulp, and paper. A bulk carrier was approaching on its way upstream, so I rowed closer to the Oregon side, waved to the GIOVANNA as it passed me at a stately 8 knots. While its wake rolled under me, I checked my phone for other traffic. There wasn’t any, so I turned downstream and pulled steadily for another half hour. The fog lifted and the breeze that had brought it upriver softened, and the sun peeked through holes in the gray. I approached Lord Island and turned into the protected channel behind Lord and Walker Islands. It was a quiet green passage, just water and trees, with not a boat on it. The sun sparkled on water rippled by an afternoon westerly. Egrets, seagulls, and Caspian terns called as I rowed toward Green Point, an expansive granite wall covered with moss and topped with tenacious trees. Riding an ebb that would last until about 6 p.m., I was averaging just under 5 knots.

An abandoned fish-procesing plant and net-drying shed at Mayger still stands on on the Oregon shoreline though the pilings holding them are all tilting upstream in a very slow collapse. In a few years it would all come tumbling down.

The afternoon wind created a mild chop, so I pulled to find protection behind Wallace Island. I saw calmer water between Wallace and Cooper Islands, but the slough there turned directly into the west wind. There MAC yawed between every stroke. My speed decreased to 2 knots, and my energy was draining fast. I looked for a place to beach MAC and make camp. I spotted an abandoned dock with a large clump of weeds at its end. There were no houses or barns in view, so I decided that no one would be alarmed if I tied up there for the evening. With MAC tethered, I wolfed down dehydrated pear and apple slices and made some tea. The effect on my demeanor was wondrous. The wind rose to a steady 15 knots and MAC tugged on her bowline. Her outriggers were banging hard against the dock. With five lines I finally secured MAC firmly away from the dock. I sat again on the dock, my spirits sagging as the wind buffeted me. Just up the ramp was a flat strip of mowed pasture grass with a tall hedgerow running parallel to the river. I set my tent where there was least wind and positioned its door toward the dock to keep an eye on MAC. The dock buckled and jerked in the waves. I’d have to use earplugs to get any sleep.

With the wind at a steady 15 knots MAC bucked and tug on her lines. I had to reposition her after the outrigged oarlocks started banging hard into the vertical edge of the dock. I could see gouges. Not good for the dock, not good for Mac.

It was a fitful night with a dog barking nearby, cows mooing, cars driving by on the other side of the hedgerow into the wee hours. I was awake at 5 a.m. The wind had softened and I quietly broke camp, loaded MAC, and shoved off, drifting happily while munching on crackers, cheese, and a bit of jerky—enough sustenance to get me back into rowing. In the morning stillness the overcast thinned as the sun rose. I headed for the Oregon side of Puget Island, thinking that if the wind did come up I’d find more protection there. I rowed around the island to its downstream end. There I found a B&B owned by Carol Carver and George Exum. They invited me to breakfast, and I would have stayed there that night had there been room. But Carol called another B&B and arranged for the proprietress to meet me in Skamakowa, another 5 miles down river, and the end of my voyage. George recommended I take a backwater slough through the Julia Butler Hansen Wildlife Preserve, so I headed for the Elochoman Slough.

I passed through the narrowest part of the 3-mile-long slough at high tide, the only time a boat with a 16’ wingspan would have rowing room. The passage was filled with great blue herons, northern harriers, geese, mallards, and Columbian white-tailed deer. I was startled by a four-point buck at the edge of the sedge grass, and we both jumped. The downstream end of the slough joins the Columbia and I rowed another mile along the river’s edge to Steamboat Slough, the quiet channel that would take me directly into Skamakowa. I rowed slowly, knowing I’d soon be leaving the river. There was a whole archipelago downstream from Skamakowa that I wanted to explore. I didn’t know when, but I knew I’d be back to wend my way to the Pacific, 33 miles downstream.![]()

Dale McKinnon began rowing in 2002 at the age of 57 and in 2004 rowed solo from Ketchikan, Alaska, to Bellingham, Washington. In 2005 she rowed from Ketchikan to Juneau. The Salish Sea of Washington and British Columbia is her playground. She lives in Bellingham near her grandkids, with her partner, Berns, and chocolate Lab, Thea, and builds the Oarling for other rowers.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your travels in a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Bravo!

Great adventure, well-told.

Dale, thank you for giving us this nicely written rowing adventure story and great photos of MAC. I hope you will give us another story.

Bob, thanks for your kind words. I’ll write about rowing the last 30-plus miles of the Columbia through the Lewis & Clark National Wildlife Preserve sometime in Spring 2015, maybe earlier. The story will include rowing over the Columbia bar into the Pacific and turning north… It’s a bucket-list kinda thing.

Wow! What a bucket!

Great trip! Very well told with just enough detail and plenty of action. I can’t wait to read about crossing the bar. Good luck to you and thanks for sharing your adventures.

Dale- Great story and photographs. Looking forward to more stories.

I am finishing out a CLC Annapolis Wherry tandem I built in September (with same rowing unit you use) and hoping to do some longer rowing trips this year. I’m about your age so would you say 25 miles a day is a reasonable plan for a trip with enough time to stop and smell the flowers?

I checked in with author Dale McKinnon: “25 miles is good. I split my days into to two segments, about 4 hours in the very early morning, before the wind comes up, and 4 hours in the evening after the wind dies down. I don’t like bucking the afternoon breezes, and instead sleep or… smell the roses.”

I am planning to go from the Bonneville dam to the bar in September in a canoe. This story was very helpful. Thanks. Good luck on the rest of your trip.