I should begin with a confession: I am quite ignorant about wooden boats, even about boats in general, but I do love them. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been tying logs together and trying to get on the water in whatever small boat came my way. I had a coastal cruise in mind, but I couldn’t find the boat I wanted for anything close to a price I could afford, so it was clearly time to build one myself.

After reading whatever books about building wooden boats I could get my hands on, I was convinced that I could turn a pile of lumber into a boat with little more than a handsaw and a hammer. I just needed a workshop.

Greg Goodman

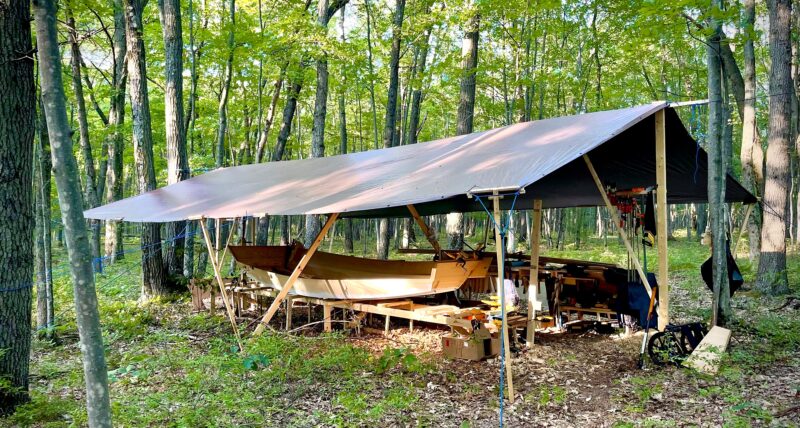

Greg GoodmanBecause we camp year-round, we tend to wear out a succession of large tents that we use as our primary shelter, so we ended up spending this summer in our smaller backpacking shelter. It was cozy with both of us and our dog, but with the long days and minimal bugs, it worked quite well. The big tarp overhead was a blessing when some heavy summer rainstorms blew in.

However, my girlfriend Vida and I do seasonal farm or winery work, and our housing is provided only while we are working. In between jobs, we are on the move. I once tried to build an umiak, while in work housing, getting as far as the backbone and a pile of ribs, but couldn’t complete it before we had to move. I used some of the time I wasn’t working to hunt for an affordable workshop. Finding none, I recalled a bit of family land in western Michigan: a 20-acre parcel of woods owned by a loose collection of my relatives, none of whom apparently had ever been to the property. It could be the perfect spot to hide away and build a boat.

So, in June 2023, with work finished up in New England, Vida and I loaded our truck for the move to Michigan. On the way, we made detours to used-tool shops, Craigslist meetups, and woodworking stores, and acquired the tools I thought I would need for an off-grid boat build. When we arrived at the family woodland, a deep roadside ditch and a dense understory blocked the way into the property. We drove farther along the road into the adjoining national forest, parked, pointed ourselves toward the land, and hiked a half-mile through the trail-less woods to the site of our future home and workshop.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanThe shop and workbench are awaiting the next step in the project. It was set up quickly in a simple way, and I didn’t really work out how to organize the space until the real project began. For quite a while I was stuck firmly in the analysis paralysis phase. The delay did give me a chance to see the shop through our first rainstorm and confirm it would stay dry and remain standing in the wind.

It was late summer, and an unbroken canopy spread overhead, letting in little shifting patches of sunshine as the leaves murmured and waved in the breeze. The trees near where we’d parked had trunks barely bigger around than my thigh, but as we drew near to and entered the family property, the trees were much larger, the forest more open. Oaks and maples with trunks often too large to wrap my arms around arched high overhead in a vaulted ceiling of green. Being immersed in a lush landscape of living trees made me realize that whatever wood I built the boat with would originally be taken from a forest somewhere; a precious resource not to be taken for granted. Vida and I stopped at a quiet, open patch of sandy soil surrounded by the forest; it would be the site of our home and my boatshop.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanThe basic shop and workbench came together quickly, and it remained a work-in-progress as things went along. I was continually adding little shelves and dividers to organize tools under the bench, and I kept lengthening it to better accommodate work on longer pieces.

We had spent years living out of tents and in short order set up our camp: a two-person tent, portable charcoal grill and propane camp stove, and a few tiki torches, all under a big green tarp printed with a leafy pattern that blended in with the woods. We dug a little firepit in the sand and I fashioned a rough stand for our water jug, to make pouring from it easier. While Vida organized our things within the living space, I looked for the flattest open spot for the shop, which would be sheltered by a 20′ × 30′ tarp. I wanted to build a simple frame under the tarp to give the covered area enough height to work under. After I’d found the right spot, I went to the local hardware store for lumber while Vida explored our surroundings.

Each of the four back-to-camp walks was made awkward and slow by the bundle of lumber riding on the rolled-up towel that padded my shoulder. I set up a wooden frame to support the tarp and stretched it over the workspace. In the shade beneath it, I could feel the breeze and building heat of the day as I watched the shadows and sunlight dance from the forest floor to within my shop. The shop would be sheltered from the summer storms that would roll in, but in fair weather I’d be free from confining walls.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanWhen I stumbled on a photo of Pete Culler’s rowing and sailing sampan design, I knew I was getting very close to the boat I wanted. Its length-to-beam ratio, rocker, and flare of the sides became my starting point. I sketched Pete Culler’s hull, then firmed up the dimensions and shape I wanted for my own design. I left the interior blank, deciding it would be easier to lay out when the hull’s shell was complete and I could see how much space I had to work with.

It had been a busy first day and, as the sky changed colors above the darkening trees, we roasted sweet potatoes in a small fire, cooked some rice and lentils, and opened a bottle of sparkling wine. We let the fire die down while the birdsong and drumming of woodpeckers faded into a quiet evening. As dusk turned to darkness we crawled into our tent, and the sounds of the lively forest night began. There was no wind, but some nocturnal animals were making the leaves rustle, an owl hooted from a perch close by, and coyotes yipped and howled in the distance.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanInitially I used the strongback as a sawing bench, as I am doing here while ripsawing the boards I glued up for the transoms. The low height seemed easier to work with for longer cuts. In the end I found that a slightly higher level worked better for me, and I switched to using the backside of the workbench where the ground brought me up to a good level.

In the morning, after coffee and oatmeal, we took a walk in the woods with our dog, Turtle, before I made another trip to the hardware store for materials for the boatshop. The walk back was especially awkward carrying 8′-long half-sheets of 1⁄2″ plywood for my workbench. I had them ripped to width at the store so I didn’t have to tackle that chore with my handsaw—a cordless drill was my only power tool. When the shelves were finished, I loaded them with my tools and prepared to get to work on the real project.

There was just one small cause for delay: I hadn’t yet decided which boat to build. I scanned the books I’d brought and skimmed through design catalogs online (my phone had great service at our campsite). I was looking for something easy to build, sleek enough to row all day, short enough that it would not require scarfing every single plank and longitudinal piece, and stable enough to accommodate fishing, a rambunctious dog, and a novice sailor in a breeze. I wanted to do near-shore sail-and-oar cruising and have space to sleep and cook aboard as well as stowage for a couple of weeks’ worth of food and water. I knew I’d found my boat when I stumbled on the many slab-sided scow types. Pram-bowed garveys, sampans, and traditional wooden johnboats all seemed to have the right stuff: johnboats could carry heavy loads, garveys were fast downwind sailers, and sampans rowed well. But the designs I found were either too big or too small, and few had the lapstrake construction I was drawn to.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanI started beveling the chine and garboard with the drawknife, initially just eyeballing for fairness by looking at the bottom edge compared to the crosspiece of the single mold I used. The long, curving blade meant I could get big sweeping, slicing cuts that removed a lot of material very quickly.

While I had been searching for a design, I had been gathering materials by prowling Craigslist and visiting local sawmills and lumber outlets.

I bought thick stair treads of lovely, clear, yellow pine being sold from the back of an abandoned semi-trailer, white oak boards from a huge local lumber distributor, northern white cedar from a father and son sawing local woods at low cost, and bargain-priced white-pine boards from another local sawyer. Only the stair treads were surfaced on all four sides, so in my growing pile I had a lot of lumber I would have to smooth and plane to thickness by hand.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanThe huge pile of northern white cedar seemed like more than enough to plank the bottom of the boat until I started sorting for clear pieces or those with only small tight knots. Starting to lay them out made it easier to see the boat taking shape.

Eager to begin, I gave up on finding plans and made a simple drawing of the boat I thought would work. The plan and body and profile had just a few lines to them: sheer, chine, and transoms. The boat was simple enough that I didn’t need to loft it. I drew the lines of a 15′ boat with a 5′ beam at 1:12 scale on the top of my workbench, not to take measurements but to visualize the shape and proportions. I mostly fit things to the parts of the boat as I went along.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanI screwed down a few thin pieces of wood to the workbench to use as stops for the bottom planking while I planed it to the proper thickness. A trigger clamp and a small block of wood on the outside edge were then enough to hold the board securely. I sharpened the jack plane’s blade with a very slight curve on the corners to allow for a smooth final surface without plane marks.

I was ready. I started with the two transoms, which would be glued from my perhaps-too-thick boards of 1 1⁄4″ southern yellow pine. Daunted by my first big rip cuts without power tools, I decided I’d better sharpen my 26″ handsaw. I made a saw vise from a scrap piece of pine and clamped it to my workbench with the saw teeth sticking up just to the gullets. I did my best to sharpen the ripsaw’s chisel-like teeth. I’d done the job half-heartedly before, and the results made it clear that it would take practice to do it properly. But with every little challenge I realized that each day’s work, even if learning how to sharpen a saw, was as much the point as was finishing the project. Every day I worked, I was building a boat, and it didn’t matter if I didn’t finish it or it didn’t float or I didn’t like what I ended up with. It was all part of the experience I was after.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanI considered attaching the side planks while the boat was upside down, thinking this could make it stiffer before I rolled it over. But I decided that riveting the lap with the garboards in that position would be unnecessarily difficult, and flipped the boat before continuing with the second strake.

As I ripsawed two 16′ pieces of 1″ white oak to make the chine logs, I flipped the pieces over and back again to make sure the kerf followed the lines I’d drawn. I grew frustrated and wondered just how long it was going to take. But in that moment of impatience, it occurred to me that slow progress was acceptable, and could even be pleasant. Every little step in the process, one after another, could take me down the long and winding path I’d chosen. As the saw purred and let fall a flurry of sawdust, each stroke took me along the beautiful grain of that lovely piece of white oak.

But as a wandering mind on a rocky path causes a stumble, the blade wavered from the line. I backed the saw, realigned it, and focused on each little bite the teeth took out of the pencil mark. There was no need to rush to the end of the cut. I took a break to sharpen the saw and got back to my little oaken path that was redolent with a warm, nutty, vanilla aroma.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanThe bottom was primed, and the runners were fitted and bedded in roofing cement. At that point I flipped the boat and was ready to put on the second strake. The low morning sun would sneak in under the tarp edges and illuminate the waiting project.

When I left our camp to pick up stock for the side planking, I expected I’d need to have the boards planed to a finished thickness of 1⁄2″ as that task seemed too great to tackle with hand tools. When I reached the sawyer’s place, he let me clamber about in his dusty barn to look over huge stacks of eastern white pine that had been cut in New Hampshire, somehow landing in a massive stack in this barn in Michigan. Thick joists, fissured and dark with age and draped in cobwebs, served as handholds as I wobbled across the tops of 10′-tall tilting towers of planks. The metal roof radiated a sauna-like heat, and a mix of dust and sweat was soon streaking down my face. Some boards were warped and checked, damaged by too-tight strapping. Others had been cut comically short and seemingly served only to fill and balance a tilting stack. Long after the owner had grown bored and left me to hunt on my own, I found a stack with beautiful, wide, clear boards. I know white pine is looked down on because it is soft and prone to rot, but I’d heard enough budget-minded folks praise its surprising quality as planking stock. The boards were 16′ long, a laborsaving 12″ wide, 3⁄4″ thick, and cheap. I climbed down with each find and eventually had a pile of lovely stock perfect for planks.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanThe simple hinged fingers I made from lumber scraps and nails allowed me to use the trigger clamps to hold the laps together. When parallel, the gap between the fingers was maybe a millimeter smaller than the doubled planks. I used little cardboard pads to make sure they didn’t mar the planking excessively. The roves were mismatched to the rivet size, and wanted to jump off after I snipped the rivets to the right length. It slowed the process, but the end result seemed to be plenty strong.

I carried the boards to the friendly owner and waited while he took them to his thickness planer. When he was finished, he walked me to his shop space to pick up the wood. Chatting with me on the way, he said, “And don’t worry, I made sure to set the planer for a very generous half inch. It’s really an old machine, and doesn’t leave a good finish, but it will be easy to clean up from there.” We got to the wood, I took a look, and wished I had just used the full-thickness boards. The newly planed boards looked like some Lilliputian woodworker had surfaced them with a tiny adze, strolling along, randomly texturing the wood more than achieving a uniform thickness. In my early days of advice-seeking for the project I had asked about thicknessing, or at the very least, surfacing, rough-sawn planking by hand. I was told not to bother, the savings weren’t worth the time. For better or worse, I now had the chance to do some surfacing with a hand plane, on a larger scale than I’d anticipated.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanAfter a good bit of priming and painting on the inside, I installed the deckbeams. They were probably way too thick and way too close together, but being pine they were fairly light, and I hate the feel of a flexing deck under foot. I figured that without any plans to rely on for scantlings I would rather go for “definitely rugged” than “maybe adequate.” I have blocking between the beams to accept the bolts to attach the cleats, and a white cedar coaming that will get a white oak rub strip on top at a later date.

It was hard at times to smooth the vast surface of even one side of those rough-planed planks. But as I worked, I learned to keep my plane blade sharp. I started with frequent tearout, even when I tried to focus on the grain direction. But by the last board I was taking big, long strokes, easily slicing the peaks from the jagged surface as the long sole rode smoothly over the rough wood. I saved the final smoothing of all the boards for the end, and the plane took big unbroken gossamer-thin shavings, translucent and dimpled with wavering grain. Working down the rough surface turned out to be a pleasure and a valuable learning experience.

It was time to shape two of those newly smooth planks into garboards. My saw-sharpening had really improved, and after the white oak, the long sweeping curves in the thin white pine were a dream to saw. With each step of the build, I learned how to work efficiently and economically. Quicker than I would have believed, I had scarfed and steamed the chine logs, bent them around the single mold to attach them to the transoms, and hung the first side planks. I was flying along.

Vida Stamey

Vida StameyMoving day! When the time came to leave Michigan and head to Rhode Island, the cart I made to haul out the boat worked surprisingly well for seeming so wobbly. The canvas cover helped to protect the hull from being scratched or filled with debris while being dragged through denser parts of the forest.

I had been pulling the best of the northern-white-cedar boards from my massive pile for the bottom planking then setting them across the chines of the boat, when a yelping, whining bark suddenly echoed through the woods. I saw Turtle bark angrily into the forest and then begin darting frantically through its sparse understory. She ran in a circle and then flung herself to the ground, driving her face into the dirt. I ran over calling her name and she finally came to me, only to take off again wiping her face on the dirt and with her paws. The smell was unbelievable, like someone had thrust a burning tire under my nose. It made my eyes water as she approached. She had been skunked. Vida ran over with a jug of water and a small towel, and we wiped down her face and flushed the burning, nauseating spray out of the dog’s eyes. Just as her barking subsided, and Vida and I could stop yelling back and forth to each other, I saw two people approaching through the woods. Matching brown shirts, guns holstered at their hips, big stars pinned to their chests—two sheriff’s deputies. I can’t imagine what their first impression was, after they watched me running around shirtless, screaming, chasing a crazed dog.

Vida Stamey

Vida StameyI cleared this road through the woods for access to campsites I was clearing for a campground project. It made for a great sunny space to work on boat parts. I turned a simple firewood rack I’d made into a sort of shaving bench and used it to make the oars. The looms were thick enough for me to sit on while I used the drawknife to shape them.

They told me that a local hunter monitoring his game camera had called the sheriff’s department to report seeing me drive into the national forest, day after day, park my truck, unload a stack of wood, and walk off into the trees. The deputies sent to investigate were clearly caught off guard. A boatshop in the woods was not what they’d thought they would find. Evidently aware they were approaching private land, they’d stopped right at the property line, finding it as I had done, with a smartphone navigation app that shows lot boundaries. I welcomed them across the imaginary line that served as our threshold, and they crossed into our campsite. Turtle settled down, I put a shirt on, and hoped they wouldn’t notice my bare feet, black from the dirt-floored shop space. The deputies were quite intrigued by the project, one of them being a member of the marine unit of their department, and were glad to have a little tour of the shop and boat. We all laughed a bit about the situation, and before they left, they assured me that my truck was parked legally and out of anyone’s way. We spent the rest of the day trying to wash the stink from Turtle, wondering what our little tent would smell like with her in it.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanAnother move: this time leaving Rhode Island for North Carolina. Every time we loaded the boat, we got a little better at getting it on and off the too-high trailer that was the only style available for one-way moves and had the benefit of providing space for tools and materials below the boat.

With the campsite at peace again, the slow work of ripping, jointing, and surfacing the northern white cedar for the bottom planking was an absolute joy. Greg Rössel, author of Building Small Boats, describes cedar, “It is very decay resistant; stands up to abrasion very well; has low shrinkage; resists puncture; and is sinuous, pliable, and tougher than a boiled owl. It can be scarfed to get desired lengths.” The shorter pieces for a cross-planked bottom wouldn’t require scarfing for length, so I had only its best qualities to enjoy. The easy sawing, fragrant shavings, and glass-smooth finish from a sharp plane made the wood a pleasure to work with. Despite its workability, my jointing was less than perfect, and I had a few planks that were not well-fitted across their full length. This was a concern, as I was planning on tight-seamed bottom planking, without goop or caulking to keep the water out. But when the time came to plank the bottom, the cedar’s softness let the planks pull snugly against one another and made it look like I’d done a perfect job. When I had finished prepping all the planks, I had gained far more practice with the planes and saw than I’d expected: it took about 45 planks to cover the bottom.

Before the newly fashioned bottom planks could be fastened in place, I had to plane the unbeveled chine logs and garboards. I’d left them square, thinking I’d have better luck getting the bevels right when I had some bottom planks ready to lay across the span to check for a good fit.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanThe storage unit in North Carolina was a bit tight for working on the boat, but it was great to have a place to leave it and return to resume work. Not owning a trailer, being camped on public land, and regularly moving meant we couldn’t work on the boat where we were staying as we had done in Michigan.

I did the first bit of heavy stock removal with my drawknife, which peeled away long, thick curls of wood that crinkled into spiral sculptures around my feet. It was good fun, and I was excited by the fast progress, but to finish with a fair surface I needed to use my jack plane. The plane sliced long twin ribbons of oak and pine, and the wavy surface was quickly flattening. I was close to finishing the beveling when the plane hung up slightly, though it didn’t feel like grain tearing. I pushed through and the plane left behind a long oval of brilliant bronze in the middle of the cut. The sharp steel blade had sliced through one of the bronze ring nails holding the garboard to the chine. I was clearly getting better at sharpening, but I’d driven in the nails too close to where the bottom would meet the chine. Many of them were going to be exposed if I continued planing. If I left a little of the chine log unbeveled, I could save myself from cutting into the nail-filled chine and still have a wide enough landing for the bottom planking. Despite the ease with which the plane had sliced through the one nail, it would be foolish to keep forcing the blade into more of them, and I switched to the Shinto rasp. Even though the hacksaw blades form which it’s made can cut metal, it otherwise is not as well suited to the job as a plane, and the beveling took much longer than I’d hoped. Finally, I smoothed the rough surface left by the rasp with a sanding board and was ready to attach the bottom planking.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanOur last campsite before launching was on the White Oak River in North Carolina. Having the launch site right next to the tent kept me extra motivated as I worked on the finishing touches to the boat. Other visitors to the river were quite interested and excited to see a wooden boat being built and launched.

I always tried to finish up the day’s work just as I started to tire and grow impatient; continuing would be counterproductive. Vida and I would head off somewhere in the area for a walk with Turtle. Within a 20-minute drive we had lakefront sand dunes, a winding riverside trail, and a little lake warm enough for taking a short dip. Often, we’d use an outing like that to stop at a local roadside spring and fill up our water jugs and buy fresh eggs that we could keep without refrigeration. Between the fresh eggs, sprouts we always had going in camp, and the fresh loaves of bread I baked in our Dutch oven, we ate well indeed. There was a farmers’ market not far away, and over the summer we bought many baskets of berries and peaches and apricots, as well as local meat and vegetables. When folks started to notice we were regulars at the market, someone finally asked what we were up to, guessing before I could answer, that we were traveling artists. Maybe so.

For a while, building went smoothly. The bottom planking fit well and a few light passes with the jointer plane eliminated the small steps from plank to plank where I hadn’t gotten the thickness quite right. I used more ring nails and a layer of bedding compound where they attached to the chine. Vida joined me for painting the bottom, and the boat was quickly ready to flip. Flipping the hull right-side up wasn’t as hard as I had expected, though I did resort to a wooden frame and some rope and pulleys to hoist and rotate the surprisingly heavy hull.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanThe day before launching I finally got the sailing rig set up, and with a gentle breeze in camp could get a feel for how it would work. The pack raft in the background has been my tender on a few boats now.

With the bottom done and the boat right-side up, I turned to the remaining side planks. The wide boards meant only two strakes were needed. I made a dozen simple planking clamps to extend the reach of my trigger clamps to close the laps between the garboards and the sheer planks. They worked very well and held the planks firmly together. I had never installed a copper rivet and rove before, but after I watched a video about riveting on my phone, it made the process a total non-event. A straight line of shining copper rivets and roves, pressed lightly into the planking, advanced along the lapped joint, replacing the crude clamps. The garboards and sheer planks were straight along the edge where they met and ran parallel with each other offset by the 1″ lap width, so bevels were not necessary. I just had to cut gains to bring the plank ends together on the transoms, which I did using a metal guide that held my 1″ chisel, essentially turning it into a little shoulder plane, perfect for the task at hand.

Things now came together quickly. The dirt floor of the shop was covered in wood shavings and sawdust; most of my lumber pile had disappeared from the stack and become part of the boat.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanLaunch day! It didn’t take much of an incline (though it looks gentler than it was) to make the quite-heavy boat unmanageable. Taking a turn of rope around the tree kept the boat’s downhill motion under control.

I enlisted Vida’s help again for painting on primer, while I made and fit the nine frames on each side. I found some cheap pine for the deckbeams, and rough-sawn western red-cedar fence pickets that I would surface and use for the decks.

I had started this project crawling through every task. Every tool to sharpen, every stroke of the plane, every big saw cut, they all were slow, challenging, and generally ended with barely satisfactory results. Now I turned the rough-sawn wobbly-edged fence pickets into dead-flat, straight-sided pieces of decking with less effort and time than I had put into my crude 2×4-and-plywood workbench just a month prior.

With our funds now running low, Vida and I had to work again. It seemed that the boat was nearly finished, but we had to leave the camp and find a new place closer to potential employment. I had assumed we’d load the boat on a dolly and haul it through the woods, but I had grossly underestimated its weight. As I lowered it onto the dolly, it almost instantly fell to the side, bending the wheel hubs and the brackets that held the wheels to the frame. It was back to the truck and out to a hardware store, where I bought wheelbarrow wheels and threaded rod for an axle. With some shimmying and sawing I turned the strongback into a trailer, with a 2×4 up front for me to lean into while dragging and shoving the boat along. The trailer was ungainly and wobbly and carrying the excessively heavy burden of the boat and strongback. I can’t say exactly how long it took to get the boat out to the road where we had parked. I tried not to keep track of time. It was only a 15- to 20-minute walk on foot, even when I hauled materials in. But the width of the boat made the sparsely wooded forest seem suddenly dense, and the wheels couldn’t roll over more than a small stick or hummock. The nearly straight path we’d worn from truck to campsite was no help. I meandered along an absurdly circuitous route through the forest. I often walked ahead to check spacing between trees, backed up, and cleared brush. All the while I was smiling thinking of the overland haul as the boat’s first journey.

Vida Stamey

Vida StameyLightly laden, the boat bounded upriver against the slight current with ease. I was used to rowing much sleeker craft and wasn’t prepared for how well a boxy boat can move through the water.

Vida and I drove back to New England with the boat in tow on top of a rented utility trailer. We settled into another camp at an abandoned and extremely overgrown Christmas tree farm in Rhode Island. I worked clearing roads and campsites, and Vida found a job at a local vegetable farm. I was allowed to clear some space in a wooded area of the farm for my new boatshop, which I made much smaller and simpler. This time I put up a simple rope ridgeline and used a much smaller tarp, only 16′ by 20′. Some smaller spruce Christmas trees had grown perfectly straight, reaching high for sunlight in the now-dense planting. I felled and barked one of them, setting it aside to dry, thinking it would probably make a great mast. Vida and I worked, and I pecked away at the remaining boat projects.

Luckily, we had landed close to another small family-run sawmill. The whole family worked together, turning out piles of beautiful lumber, and providing great friendly service. They sold me a nice rough-sawn ash 2×10 that I could use to make a pair of oars. I worked, again, without power tools. After roughly sawing and shaping the oars, I snapped out a rectangular piece of thrift-store saw blade, and filed a hollow into one edge to make a scraper I could use to remove the plane and spokeshave marks from shaping the oars. They were much heavier than they would have been if I’d used spruce, but I’ve snapped enough paddles and oars in the past to know I wanted something rugged to propel a sure-to-be heavy craft. Despite their heavy weight and rough finish, I was proud of them, especially after I’d laced the leathers on them, and protected the blade tips with folded copper sheet.

Vida Stamey

Vida StameyLaunch day was my first time sculling a boat. I had made a raised sculling notch over the stern to have an alternative way to propel the boat and to hold the steering oar in place while sailing. I found sculling to be delightful, and when the river became very narrow and clogged with downed trees, it became essential.

Everyone had told me that making and installing the myriad small pieces were the real work of building a boat and took the most time. I’d been doubtful, but after making the maststep, partner, floorboards, cleats, fairleads, oars, and tholes, I was convinced. It seemed like I would never be done with every little piece. Then—all of a sudden—the mornings were frosty, and it was too late to do all the oiling and painting I wanted to get done before launching, and I was greatly disappointed.

With the frost came the end of our work, and it was time to move again. With a job waiting for Vida in Virginia, but still a couple months away, we had another spell of free time and headed south early. As the new year kicked off, the boat got dragged onto a rented trailer once more, with my tools, scraps of wood, and half-finished bits tucked underneath, and we headed for North Carolina to be someplace warm, quiet, and closer to Vida’s upcoming job. I was determined to put the boat in the water before another big move, and I didn’t care if all the work was finished or not. We got a storage unit and used it for a workshop, commuting to the unit from wherever we’d camped in the nearby national forest. After we painted the boat and oiled the oars, spars, decks and all the little bits of trim with boat soup (a mix of pine tar, linseed oil, and turpentine), the next move was to a campsite on the banks of the White Oak River. I roughed out a few final pieces, but any remaining details that could be ignored were left unfinished or absent. I was just too eager to get on the water.

Vida Stamey

Vida StameyTurtle is investigating her new floating home while I wave farewell and start what I thought of as sea trials: a few days rowing down the river to see if the boat felt suitable for venturing off into bigger water.

A few days after the move, a short spell of cold weather and frosty mornings gave way, and we woke to a sunny morning, full of birdsong, warmer than any day for weeks. It was easy to forget it was still winter. The meandering swampy river was perfect for a first sea trial. We blew up our beach rollers, and slowly rolled the boat to the water. To reach the river we had to lower the boat down a steep muddy bank with a line secured to a cleat on the bow. It was a tense moment, as it was the first cleat I’d made and I had no clue what kind of load it could take. As the boat dangled precariously at the water’s edge, with the rollers bent and twitching over logs and rocks in the bank, Vida held the line while I kept the rollers in position and guided the boat over the uneven terrain. Finally, the stern dipped inch by inch into the water, its wide flat expanse rising easily, lifting the boat off the first roller, and then the second, and then swoosh: the line was released, and the boat slid out into the dark swampy water. We pulled the nose back to shore and christened her the MUDDY TURTLE. We celebrated by pouring ourselves each a glass of sparkling rosé, with a splash over the bow for the boat as well.

Floating high and easy and drawing about 7″, her simple workboat lines and finish were perfectly at home in the dark-stained water and among the cypress trees. Already a little muddy from her trip down to the river, the name MUDDY TURTLE instantly felt appropriate, and I was glad I’d taken the time to carve the little mahogany nameplate and burn in the lettering. It gave a little more presence to the big flat trapezoidal transom. I stepped from the shore straight onto the foredeck, and perched at the very bow of the craft, surprised to be comfortable and easily able to balance. I shoved off with the coppered blade of my oar and walked easily back to the stern to drop it into the sculling notch.

Greg Goodman

Greg GoodmanAbout 10 days after launching, I anchored in a little tidal stream next to Fort Macon in North Carolina. I was starting to get into a rhythm, and finally stopped worrying that I would wake up floating on my sleeping mat while the boat was filling with water around me.

Within 24 hours of the launch, I was underway on a test row down the river with Turtle while Vida headed to the river mouth to set up camp where we would rendezvous. A few days later I got to the end of the river, but I didn’t want to stop. So, Vida took the truck and headed to work in Virginia, while Turtle and I set off for bigger water to see just what the little boat could do. The short sea trial turned into a six-week meandering solo cruise, exploring almost 400 miles of North Carolina’s bays, rivers, and ocean coast. My beautiful little boat came to prove that ignorance can, when it comes to boats, lead to bliss.![]()

Greg Goodman grew up alongside a little river in Connecticut. Eventually he realized that his backyard stream flowed out into Long Island sound, and ultimately connected his yard to the whole world. He became instantly interested in using small boats to enjoy all the beautiful places bound together by water. Travel in many forms has dominated his life thus far, and he has been almost constantly on the move for the last 18 years, stopping for seasonal work, or spectacular places that occasionally keep him in one spot for more than a season. He is rarely without some kind of small boat, and has enjoyed many miles of paddling, rowing, and sailing in the U.S. and abroad. He is currently making his way to Washington state, to find work, build another boat, and then kick off another water adventure.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great project Greg! I must admit that I am secretly jealous of the nomadic lifestyle you have chosen. Your resourcefulness is impressive, and it looks like TURTLE will be a great boat for your future adventures. When you do make it to Washington state, look me up (I’m in Lake Stevens) and we can go for a sail on BONNIE LASS.

Thanks for the friendly comment and invite! Would be good fun to join for a sail on BONNIE LASS sometime.

Hope you’re having plenty of boating fun for the summer!

Great story, nice boat!

I particularly enjoyed this article as I have a similar experience. I once built a 14′ flatiron skiff for friends in NH using no plans, lumberyard pine and hand tools. That boat was a success too. Fair winds!

-John S