Before Sam Devlin fired up the motor and backed the Banjo 20 from the dock, the two of us relaxed in the cabin and chatted about boats each of us had designed and built, family, and getting older. Before even casting off, the trailerable 20′ outboard pocket cruiser Sam had designed had lived up to one of its primary purposes: providing a comfortable place to welcome company. The geometry of the interior’s conduciveness to conversation was not incidental. The footwell has room to sit facing one another without crowding feet or knees and the benches are comfortable and set the cabin occupants neither too close to nor too far from each other.

I had met with Sam to take notes on the Banjo 20’s underway performance, but I was content to let the time slip by with the boat still tied to the dock. We did eventually cast off and get underway.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe airy cabin has a pair of 7′ 2″ benches. Six portholes and a skylight hatch brighten the space.

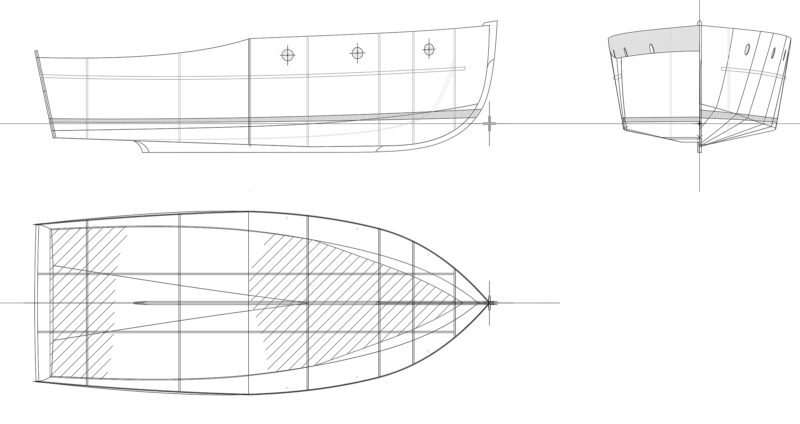

The Banjo 20 is built of plywood in the stitch-and-glue method that Sam pioneered in the late 1970s and detailed in Devlin’s Boat Building: How to build the stitch-and-glue way, first published in 1995 and updated in a second edition released in 2023. Plans for Banjo consist of 16 sheets of drawings, clear and easy to read, computer-rendered in color. They include a partial list of wood needed for the hull and deck and measured drawings in metric and imperial dimensions for the seven 18mm bulkheads that serve as molds, the transom, the 12mm side and bottom panels, and the doubled 12mm “ski.” The ski is an elongated triangle with its 39″ base at the transom and its apex on the centerline, 8′ aft of the forward perpendicular. It creates a flat planing surface at the aft 12′ of the hull where there would otherwise be a deep-V.

A porta-potti hides under a hinged seat. Behind it is a hatch that provides access to a storage space and a shelf that serves as a galley. A wood-burning stove makes chilly days and nights more comfortable.

The plywood panel edges get a 45-degree bevel along half the thickness to avoid the struggle to accurately align sharp, 90-degree corners with each other. The seams are given fillets of thickened epoxy inside and 6-oz biaxial cloth is applied inside and out. The exterior of the hull is sheathed in 6-oz fiberglass cloth and a layer of Dynel.

The keel and stem are a laminate of three layers of 3⁄4″ marine plywood, cut to fit the contours of the hull along the centerline. Fillets of thickened epoxy fair the backbone pieces into the hull and ’glass finishes the connection.

The drawings provide the information needed to build the boat without lofting or spiling but do not include a step-by-step guide to construction; Sam’s book will serve in that capacity. For a newcomer to boatbuilding, a smaller stitch-and-glue boat would be a useful hands-on introduction to the method.

The companionway at the aft end of the cabin has a folding door and a hinged hatch that open to provide easy passage to the pilothouse.

The aft end of the cockpit is open for 49″ of its length. Flanking the outboard-motor well are decked-over compartments for fuel tanks, easily accessed by openings in the bulkhead.

The 3⁄4″-plywood cockpit sole is above the waterline and self-draining. It is slightly convex and that 1⁄2″ of sway guides any water that accumulates to a drain pit, set under the motorwell, where it can be pumped overboard.

The skipper and a companion are protected from the elements by the pilothouse, which is open aft in the standard arrangement. The plans include details for fully enclosed accommodations.

The 6′ 10″-long pilothouse roof provides cover for the skipper and a passenger, with 6′ 6″ of headroom except for the roof beams that take up just 2″ of that clearance. Pilothouse seats are not detailed in the plans; commercial pedestal seats are bolted in place. The roof also offers protection for the cabin companionway and a flat interior extension of the foredeck where charts and other items needed while underway can be kept. The accommodations for the motor controls, wheel, and instrumentation are left up to the builder. The last sheet of the 16 drawings provides details for enclosing the aft end of the pilothouse with a bulkhead and a 24″-wide hinged door.

The companionway has a flat hatch cover, hinged at its forward end. When open, a hook, mounted on one of the beams supporting the pilothouse roof, engages an eye fastened to the side of the hatch. A bifold door opens the passage to the cabin. It’s a 10″ step down to the cabin sole; with the hatch cover open, there is standing headroom, so there’s no need to duck while stepping into the cabin. Forward of the opening, there is about 4′ 10″ between the sole and the roof.

On both sides of the motorwell there is plenty of covered space for fuel tanks.

Three portlights on either side of the cabin, along with a foredeck hatch/skylight, illuminate the interior. All can be opened for ventilation.

The side benches have good headroom and the back-rest cushions, held in place by snaps to make them removable, are set at a comfortable angle. The benches are 7′ 2″ long and can serve as berths; at their forward end they are 26″ wide. A builder looking for more sleeping space could make panels to insert over the footwell and use backrests as cushions there.

The Banjo, with a 90-hp outboard, comes up on plane in just a few seconds and will do 28.5 knots at wide-open throttle.

A removable panel and cushion, set flush with the side benches at their forward ends, covers a space that accommodates a portable head. The bulkhead at the forward end of the benches encloses a storage compartment and supports a shelf that serves as a galley.

The gallows and canvas cover for the cockpit are an option indicated in the plans.

The plans call for an outboard of 60- to 90-hp; the Banjo 20 web page mentions “a top end of 30 mph with a 115-hp engine or an economical 15- to 18-mph cruise with a 60.” That turned out to be an understatement. The Banjo I was aboard and pictured here has a 90-hp four-stroke outboard and running straight at full throttle, the Banjo hit 32.8 mph. At an idle the engine pushed the boat along at 7 1⁄2mph. When it was powered-up, the bow rose, as expected, for about 3 or 4 seconds and then settled back down, clearing the view from the helm to the horizon. The water was merely rippled at the time of these trials and the only waves we had were the Banjo’s own wake and that of a passing fishing boat. The V sections forward cut through them without pounding. I made a few turns at speed and the Banjo stayed very nearly level while carving through them.

The Banjo was designed to be “a bridge between a serious, large cruising boat and something that is small enough to enjoy on a whim.”

Sam wrote that the Banjo 20 was “designed as a compact, trailerable outboard cruiser that could move quickly when needed. She also needed to be able to access shallow river waters as well as being able to deal with the sometimes rough waters of San Francisco Bay.” That’s the designer in him speaking. In the conversation we had before we got underway it was clear that his aspirations for the boat reflect a shift in perspective as he approaches 70: the Banjo is a cozy setting for enjoying the company of friends and family whether at the dock or out for an afternoon or a weekend.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats.

Banjo 20 particulars

Length: 20′ 1″

Beam: 7′ 10″

Draft: 18″

Displacement: 3,400 lbs

Power: 60- to 90-hp outboard

Plans for the Banjo 20 are available from Devlin Designing Boat Builders for $325 (downloadable) and $375 (printed). Devlin’s Boatbuilding Manual, Second Edition is available from Sam Devlin (signed copies upon request) and the WoodenBoat Store for $45.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Here in the tropics I would absolutely live on her.

I’d live on it on this eastern island !

Fitted out a great Colvic 21 in the 70’s. Very similar design.

Ah yes, add to the collection of boats I wish I had.

Very nice boat and practical like many Devlin designs. The boat could hit a higher speed with a 60hp 2-stroke, but alas they are mostly in the past now.

Why should 2-strokes be “in the past” as the small contribution they make to the over wrought negative effect they have on the environment is small as there are not many of them. When you consider the 2-strokes were made in the past, there is not the negative affect of power and materials used to manufacture new 4-strokes, not considering the outlay of scarce money to pay the outlandish price of a new 4-stroke. 2-strokes have been in Minnesota lakes for 100 years and the lakes are healthier than ever.