North Hero Island dipped out of sight as I looked up at two converging waves. Both were cresting, the southerly wind blowing spindrift over my head. My hands, already seized from a vice-like grip on the paddle to defy the wind, gripped even more tightly as I nosed the bow of my canoe into the slot between the waves. I began to wonder how long I could muster the strength to continue into this wind.

I had started several hours earlier in Swanton, Vermont. My wife, Viveka, had informed me that the weather was forecast to be the roughest so far: heavy rain and very strong southerly wind, the worst possible for paddling south on Lake Champlain. Her advice was to sit out the storm in the motel, but sitting still is not my style. Nor is getting behind schedule.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneMy canoe is one I designed for fast solo travel and built light for easy portaging. For the Northern Forest Canoe Trail, I added some extra fiberglass on the bottom to better survive the inevitable collisions with rocks. Even with the reinforcements, the canoe weighs just 37 lbs.

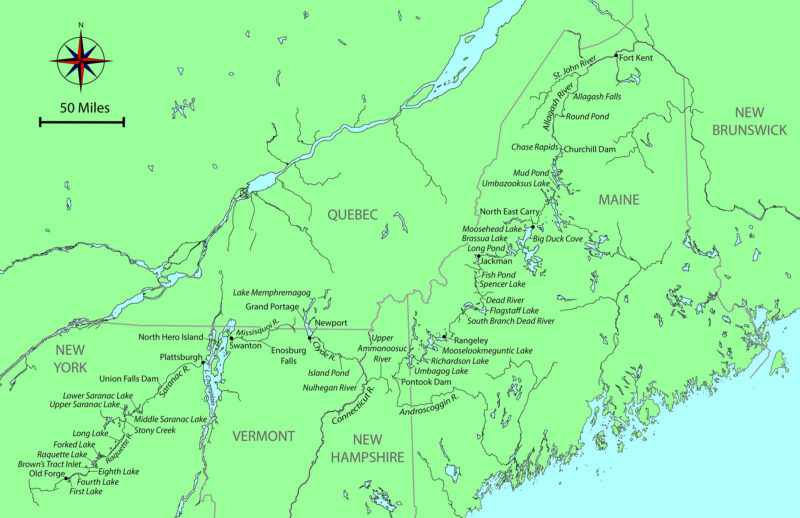

This was three weeks into my 2018 through-paddle of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail (NFCT). I had first paddled the trail five years previously, a solo trek of over 750 miles in 28 days, in a 14′ cedar-strip canoe that I designed and built. I was now paddling from east to west, from Fort Kent, Maine, to Old Forge, New York. If successful, this would be the first recorded backwards through-paddle. Of the trail’s 13 major rivers, the conventional direction–west to east–involves paddling nine downstream and four upstream. Nobody in their right mind would go “uphill” from east to west. Part of my motivation was to be the first. The challenge would involve many miles of paddling against the current, rapids, and prevailing headwinds.

On the eve of traveling to the launch at Fort Kent I spent the night in Shelburne, New Hampshire, with friends Ray and Hildy. When I woke and opened my eyes, the first thing I saw was the spine of one of the books on the shelf next to the bed: The Darwin Awards.

The long drive to Fort Kent that day, May 13, was not without trepidation. Just two weeks earlier, the St. John and Allagash rivers, the initial upstream run of over 90 miles, had been in spate with meltwater, and the Allagash had burst its banks. I had watched online as flow rates fell frustratingly slowly, while webcams showed an unusually slow retreat of ice on the lakes. When we reached the levee in Fort Kent, we climbed to the top for the moment of truth. Would we see the St. John at a navigable level? Or would we turn around and take the long road home? Although the river was still above the seasonal norm, it was no longer a raging torrent. The next morning, I launched under a cloudless blue sky, bade farewell to my support crew, and paddled west, ascending the St. John River.

Ray and Hildy Danforth

Ray and Hildy DanforthLeaving Fort Kent to begin my ascent of the St. John River, I was immediately focused on the first challenge: crossing the outflow of the Fish River, less than 100 yards upstream from the launch ramp. The black spike-like steeple rising above the far bank marks a church in the town of Clair, New Brunswick. For 16 miles upstream, the river separates the US from Canada.

The start, up the St. John and the Allagash to Churchill Dam, was against the flow, including several rapids. Where depth allowed, I used my long-bladed ash paddle. In shallower water, I turned to a shorter paddle with a wider blade. And where rapids started, I turned to my poles, a pair of ski poles. Kneeling to double-pole, I pushed off the rocky riverbed and propelled the canoe forward this way for several miles. On the first day, I ascended nearly 24 miles of the St. John. and on the next day I pushed upstream on the Allagash and made the first carry of the trip at Allagash Falls. The NFCT includes over 50 miles of portages around obstacles and over watershed divides. I continued on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. At the end of the third day, I stopped not far from the foot of the Chase Rapids, the largest and most powerful on the Allagash. I had worked hard, putting in 12-hour days to reach here, in order to tackle the nearly 5 miles of rapids while I was fresh in the morning.

There had already been several hard frosts, and overnight the cold had turned my drinking water to ice and frozen my toothpaste and neoprene-lined boots. I had to boil extra water to thaw the boots; together with a pair of dry-pants, they were excellent for wading where the current was too strong for poling. I had slept well in spite of the cold. The hammock under-quilt I’d made from an old sleeping bag was highly effective.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneBy camping with a hammock I avoided the need to find even ground, and its absence of rigid parts made it easy to pack. My camp here on the bank of the West Branch of the Penobscot River, near the mouth of Pine Stream, was quite remote but furnished with a picnic table.

I was now down to one ski pole. I had lost the other while wading up the rapids downstream from Round Pond. It must have been flicked out by springy vegetation on the bank, and I could not face returning downstream on a likely wild goose chase. While my solitary pole was useless for propulsion, it kept me upright when wading on algae-coated rocks.

I launched into Chase Rapids and the initial eddy-hopping was a thing of great beauty, accelerating up one eddy behind a rock and crossing the flow to another eddy. Where the current was too powerful I waded, and where there were falls I heaved the loaded canoe up over them. I had been making astounding progress but about 1/2 mile from the top end of the rapids, I slipped on slimy rocks yet again and decided to take the portage trail rather than risk injuring myself.

I arrived at Churchill Dam at the top of the rapids ahead of schedule, having ascended two major rivers in under four days. As I then gained a few miles, the Allagash headwater lakes, rimmed with green conifers, glistened under bright sun.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

The Mud Pond Carry, the next day’s challenge, is an historic portage between Umbazooksus Lake and Mud Pond, something of a rite of passage. Five years ago, I had avoided this 1.7-mile trudge through deep mud by taking an alternative route, and now was my chance to earn my stripes. I paddled on a compass bearing across Mud Pond to find a small inlet where I expected to find the portage. I’d been singling the carries, taking everything at once, so I loaded the pack on my back, lifted the canoe overhead, and set out on a floating bog that sank beneath my feet at each step. Soon I was on dry ground, thankful for the lack of spring rain, but the easy going didn’t last long. I arrived at a very deep bog and had to detour around it. The path I found soon became overgrown with young trees. I pushed the canoe into spaces that resisted my efforts to squeeze the canoe through, so I backed out. After a few such shunts, it was clear that I was not on the trail, and retracing my steps soon became impossible; pressing forward on a compass bearing was my best hope.

Finally, the saplings closed in so tight that the canoe would not fit through them. I was stuck and lost deep in the Maine woods. To make matters worse, my water bottle was nearly empty and it was the hottest part of the day. A wave of panic surged through me. I knew there were roads to the west and south, so I could rescue myself, but I’d have to abandon the canoe. That option was almost unthinkable and so I had nothing to lose by forging ahead.

I used brute force to ram the canoe mercilessly between saplings, splaying them apart. I kept at it, making a few feet with every effort, and suddenly emerged into a region of felled trees. In sheer relief I danced from trunk to trunk, before stopping to take stock of my situation. I discovered that my camera, which I’d strapped to my pack belt, had been torn away somewhere in the brush. Lost with it was the record of the trip up to that point. After filtering a little water from a post hole, I searched for the camera, but only briefly: losing track of the canoe and pack would have made a bad situation worse. I dejectedly resumed the trek, following the line of felled trees to a road, which led to the foot of Umbazooksus Lake.

I had singled the Mud Pond Carry, but at a great cost and not by the traditional route. The rite of passage I had hoped for had remained unfulfilled. I paddled with sadness down Umbazooksus Stream, the first short downstream for which I had worked so hard. Partway down this stream, I remembered that my phone could take photos, and if the sun kept shining, my solar charger would recharge it.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneLaunching through the breaking waves at the North East Carry into Moosehead Lake was the first challenge here; paddling against the wind was the next.

Headwinds had plagued me since the start at Fort Kent and, as I was ascending the West Branch of the Penobscot River, a strong southerly sprang up. After traversing the North East Carry, a 2-mile portage from the Penobscot, I arrived at the northern end of Moosehead Lake. At 33 miles long, it is the largest lake in Maine. The southerly wind was now blowing at 20 to 25 mph. I abandoned plans to aim for the exposed Seboomook Point, 3 miles to the west, in favor of a more sheltered campsite farther south on the eastern shore. Either site would require launching into substantial surf.

I enjoy the glide of the canoe and the rhythm of paddling, but there was none of that in this headwind. Every stroke required great effort and accelerated the canoe from a standstill. I inched south along the eastern shoreline just outside of the breaking waves. Blocks of broken ice at the water’s edge reminded me that ice-out here had only recently occurred.

At the end of another 12-hour day I pulled into a campsite in Big Duck Cove, exhausted, having covered 29 miles upstream and into the wind. It had been hard work to keep from going nowhere or even getting pushed backward.

Strong headwinds continued to haunt me. The next day, I headed west from Moosehead Lake up 3 miles of the Moose River to Brassua Dam. Emerging on Brassua Lake a strong northwesterly made paddling a struggle, and I ended the day on Long Pond beating into a 25-mph westerly.

Later a strong southerly would slow me on Fish Pond and Spencer Lake, and I would travel much of the 18 miles of Flagstaff Lake into another headwind just as strong.

When I reached Jackman, Maine, I took a half day of rest in the motel where I had mailed a food package, the first resupply of three. I took a shower, my first since launching eight days before—the frigid lake water temperature did not invite taking a dip to rinse the sweat and grime away. The skin on my hands had developed painful splits, especially on the exposed fingertips, despite wearing fingerless gloves for protection; furthermore, the extreme effort of paddling so many miles upstream and upwind was affecting my shoulders. At night, shooting pains radiated along my arms. And having to grip the paddle extremely hard for long days, merely to keep hold of it in the strong wind, my fingers were now seizing up overnight and required much coaxing to flex again. I needed a rest.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneMost of the South Branch of the Dead River had too little water for paddling. The upper reaches had just enough water, but were obstructed by fallen trees.

From Jackman, my route took me farther up the Moose River before a carry to Little Spencer Stream, which, with its impoundments of the mile-long Fish Pond and the adjoining 4-1/2-mile-long Spencer Lake, led me down to Spencer Stream and the Dead River. More upstream work on the Dead River brought me to Flagstaff Lake, above which the South Branch of the Dead River is often bypassed due to low water. I ascended the first 3 miles of it, but there was not enough water to sink a paddle. The river was so low that I faced wading almost the entire length on slippery rocks; carrying along the Stratton–Rangeley road that paralleled the river was the better option.

I escaped to the road at the first bridge, and that day carried a total of over 17 miles, putting into the river only for the final 3 miles above Fansanger Falls. The last 4 miles of carry over the watershed divide to the town of Rangeley were to reward myself with a night in a B&B.

The struggle against headwinds continued as I traversed Rangeley, Mooselookmeguntic, and Richardson lakes. On Mooselookmeguntic, the wind made my ears vibrate with the ripping noise of a flag in strong wind.

Ray and Hildy Danforth

Ray and Hildy DanforthTackling the Pontook Rapids on the Androscoggin River saved carrying for 1-1/2 miles along the riverside road, but colliding with a rock resulted in a minor split in the hull of the canoe. I sealed the crack with tape, a repair that lasted for the rest of the journey.

On my 13th day, I paddled into Umbagog Lake, which spans 10 miles of the New Hampshire border. I had almost reached the NFCT’s halfway point. Umbagog drains to the west into the Androscoggin River, my first major downstream run. It was raining, but the river was everything that I wished for: plenty of flow and wonderful rapids with clear channels. The quick run lasted less than a day, but I relished the power of deep, fast water pressing against my paddle. My hard work had earned this. Below Pontook Dam, Ray and Hildy collected me for pizza and ice cream—a welcome change from dried food—a spare pole to replace the one I’d lost, and a comfortable night at their home. I slept again with The Darwin Awards smirking by the bed.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneThe upper Nulhegan River offered some fine paddling through a flood plain, as well as some upstream navigation challenges where streams converge. Tight meanders ensured that this section took longer to paddle than a quick look at the map might suggest.

Ray drove me back to the Androscoggin where I had left off so that I could carry 4 miles to the Upper Ammonoosuc River where another day of downstream across northern New Hampshire brought me westward to the Connecticut River between New Hampshire and Vermont and the Nulhegan River in Vermont. For me, they were two more upstream runs, and a tough section of the Nulhegan has some challenging, rocky rapids. Rather than carry around them, I chose to tackle these rapids upstream, balancing on slippery rocks while hauling the laden canoe up the falls, all while trying to remain calm amid an onslaught of blackflies. As the river opened out into flat meander, I looked back on the very short but tough ascent with immense satisfaction.

From Island Pond, the high point of the trail in Vermont, I paddled downstream on the Clyde River, pushing between alders, negotiating deadfalls, crossing ponds, tackling shallow, rocky rapids, and carrying around dams, all under bright sun with a tailwind. The Clyde deposited me at Newport, a town on Lake Memphremagog, just 5 miles from the Canadian border. The wind remained at my back on the lake straddling the international border, and I checked in with Canadian Customs by phone. A half dozen miles farther north, I hauled out for the Grand Portage, another half dozen miles, this time by road west to the Missisquoi Valley. Here I declined a ride offered by the person who lived nearest the far end of the carry. I doubt he understands even now my desire to be self-propelled.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneWhen I ascended the Missisquoi River five years previously, the water had been lapping at the tops of the banks. During my long descent on this journey, I scraped over many shoals.

On my two-and-a-half-plus-day descent of the meandering Missisquoi across Québec and northern Vermont I was paddling at low water between tall, steep banks, looking up at trees that I had fought through on my west-to-east journey when the same river was in flood and about 7’ higher. Farther down the Missisquoi I re-entered the U.S. and met Viveka at Enosburg Falls for a full day of rest.

At the end of the third week I was back on the Missisquoi, finishing this long downstream run. When I arrived at Swanton, 7 miles from the mouth of the river, I was ready to take on Lake Champlain, despite the weather forecast and advice to sit tight. I set out on the crossing, a mile-plus passage from mainland Vermont to North Hero Island, in a white-streaked sea of tumultuous waves. A southerly gale blowing almost 30 mph and gusting higher was tearing up both sides of North Hero, and drove waves that converged around the north end of the island to rise even higher.

The cresting waves slapped water into my canoe from both sides. It swirled around my knees as the little canoe pitched and rolled yet remained reassuringly stable; the challenge was to make progress into a 30-mph wind. I dropped my head and put maximum effort in every stroke, ferry-gliding alternately to east and west to vary the muscles in use. In this sawtooth fashion, I finally pulled exhausted into the lee of North Hero and uncurled my body, having made the hardest crossing I ever wish to make.

To have stayed there would have put me behind schedule, so, after some recovery, I continued south on the more sheltered west side of North Hero. The only overnight options were on the east, so at the Carrying Place, a mid-island neck of land only wide enough to support a two-lane road, I pushed through a 90′-long steel culvert and emerged into the full blast of the wind. Camping on Knight Island, a state park 1-1/2 miles to the southeast across open water, was now unthinkable, so I set my sights on North Hero Village, a mile alongshore to the south.

The headwind now brought me to a complete standstill. Paddling as hard as I could, I achieved nothing. Defeated, my only hope was to carry along the road. For the first 1/2 mile, a line of trees sheltered me from the wind, but beyond it the carry turned into a nightmare. I leaned the canoe strongly into the crosswind and frequently had to plant a leg wide just to remain standing. After an exhausting carry I finally arrived at an inn, booked a room, and collapsed on the bed.

The next day, feeling utterly beaten I completed the crossing of Lake Champlain in mercifully calmer conditions, coming ashore at Plattsburgh, New York. I received a text from Viveka about a body being found in this area of the lake. I replied, reassuring her by saying, “Still kicking!”

From downtown Plattsburgh I began the ascent of the Saranac River. It was flowing well but shallow and with almost continuous riffles. Paddling, wading, and poling, I completed a stretch of upstream work that I was proud of, but on my 24th day, I still had to carry around a section of tough rapids, part of another day with 17 miles of portage. This brought me to Union Falls Dam, just beyond the upper reach of the whitewater.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneThe eastern shore of Long Lake in the Adirondacks provided a campsite with a lean-to at the perfect time of day. Amid the hard work of the trip, this was a jewel of serenity.

After camping above Saranac Lake Village, I reached Lower Saranac Lake, where I experienced the most perfect paddling imaginable. With the rising sun at my back and smooth, glassy water ahead, I paddled with a sense of connection from the pressure of water on the blade through me to the flowing movement of the canoe. The experience was all the more exquisite for its rarity on this trip.

After a 2-mile transit of Middle Saranac Lake and another 2 miles across the south end of Upper Saranac Lake, I portaged to the ponds at the head of Stony Creek. Descending a looping 1-1/2 miles brought me to the Raquette River for a 12-mile upstream leg to Long Lake, an aptly named broadening of the river 14 miles long and less than a mile wide at its widest point. I ended the day cooking dinner on a sandy beach while the sun sank over the Adirondack Mountains to the west.

From the south end of Long Lake, I finished the ascent of the Raquette River to Forked Lake and Raquette Lake, where I spent the night on Big Island, a few miles ahead of schedule and poised to bring this trek to a close the following day.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneThe final morning of any long journey is a special and bittersweet moment. The mist covering Brown’s Tract Inlet leading from Raquette Lake added an atmospheric touch to this one.

The 28th day dawned misty. I paddled up an ethereal Browns Tract Inlet, a final short, sluggish upstream paddle delayed by beaver dams across the flow. After carrying to Eighth Lake, the uppermost of the Fulton Chain, I was on the home stretch, a countdown of lakes from Eighth to First Lake, under bright sun and blue sky.

Peter Macfarlane

Peter MacfarlaneFor the last few miles on the Fulton Chain to Old Forge, Viveka, Ray, and Hildy, escorted me, paddling one of my canoes.

My support crew—Ray, Hildy, and Viveka—paddled out to meet me on Fourth Lake, served me a sumptuous lunch, and then escorted me to the finish at Old Forge. On the final approach, while my friends paddled to shore, I held back and reflected.

With the end drawing near, my canoe’s wake stretches over 700 miles astern.

It had been one thing to set up this challenge; quite another to see it through to successful completion. The hard work of this trip was beyond what I’d anticipated. I expected upstream to be tough, even relished the challenge, but the headwinds had taken the difficulty to another level. Through all the trials though, my trusted little canoe had once more been my faithful companion.![]()

Following a career of teaching high school science in the U.K., Peter Macfarlane immigrated to Vermont to take up life as a musician. Playing and teaching the fiddle professionally has afforded him the time to indulge his passion for cedar-strip canoes, not only paddling them but also designing and building them as Otter Creek Smallcraft. The canoe pictured here is a Sylva, a solo touring canoe he designed, built, and paddled the full length of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail in 2013 and 2018.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.