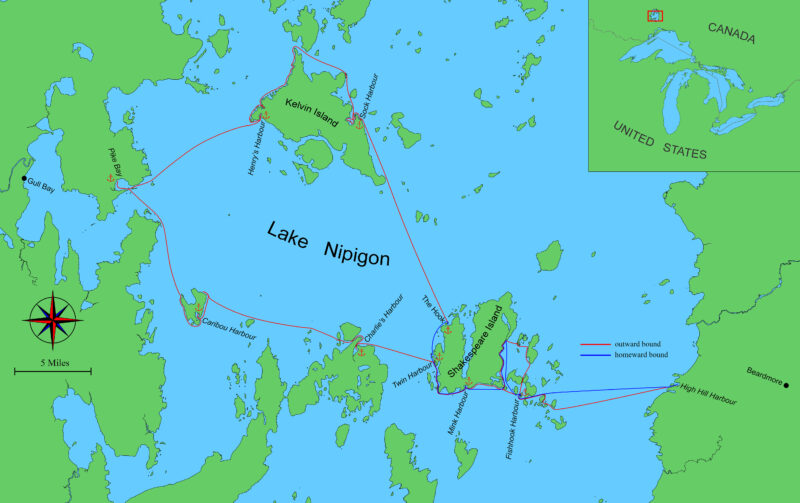

My friend Eric and I were aboard my 20′ Whitehall as we slipped out of High Hill Harbour on the southeast side of Ontario’s Lake Nipigon. With a 3-hp electric motor providing power, we glided quietly between 300’-high rock hills clad in boreal forest, and out into the wide expanse of the lake. The sky was a low, flat, winter gray; there was a modest north wind on our starboard beam, and steely gray light glimmered off the faces of the waves. I pulled the flaps of my snow hat down over my ears and turned my face from the wind. The air temperature was 41°F, and the little display screen of the portable fishfinder at my side showed a water temperature of 36° and 255′ of cold, dark water beneath us. It was the third week of May, and the winter ice had cleared only two weeks earlier. This would be no summer idyll, but the early season should be good for fishing.

Eric sat stiffly at the bow wearing a down jacket and an orange rain hat pulled down over a cloth head covering. A stubble of white beard showed below his sunglasses. Between us were two 110-W solar panels spread out on deck amidships along the starboard rail—their glossy black squares and stark white border looking out of place against the sweeping curve of the teak gunwale.

I turned the tiller throttle until we reached 4 mph by GPS and set the boat on a course that would take us west-southwest across 10 miles of open water to the nearest of the Macoun Islands—then barely visible as a thin, unbroken line of misty gray on the western horizon. With the course set, and the boat moving at a good trolling speed for lake trout, I propped a fishing pole against my seat, planted my foot against the cork-covered handle, opened the bail of the reel to let the line stream out astern, closed the bail, and watched the line pull tight and both pole and line vibrate softly as the lure wobbled below the surface far astern.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorEric tended the boat and set up his GPS for tracking while I parked the van in the gravel lot next to the boat ramp. No one else was using the ramp, and we encountered only two other boats throughout our 15 days on the water.

An hour into the crossing, I saw that the “house” battery, which stores the power from the solar panels, was not feeding the motor battery as it should to replace the power drawn by the motor. I turned the motor off and inspected all the electrical connections while Eric checked the fuses. Nothing seemed amiss. I dug the clamp meter out of the port seat locker and began testing each part of the electrical system. The meter’s digital readout showed that the solar panels were feeding the house battery properly, and the house battery was fully charged, but no power was going from the house battery to the motor battery.

We looked dumbly at each other for a long moment as the boat rocked awkwardly in the waves. We had exhausted our limited electrical know-how, and we both knew we couldn’t continue the trip if the motor battery couldn’t recharge. We began checking everything again…and again…testing and pondering and cursing in vain as the boat drifted broadside to the waves.

With no other options left, we tried the one thing that we both had agreed at the start could not possibly be the problem—we disconnected the auxiliary cigarette-lighter connection cable that I had added to the house battery so we could power an electric kettle and charge phones and satellite gizmos without disconnecting the motor. Tightening the terminal bolts back down on the house battery, I looked over my shoulder and saw the electric motor’s red charging light blink on. With a twist of the tiller handle, we were on our way.

We found a quiet anchorage that evening in one of the small, unnamed islets of the Macoun Islands, which we christened “Fishhook Island” because of its shape. Inside the hook, at its south end, was a shallow, soft-mud-bottomed bay 60 yards wide and open only to the northwest. I might have avoided an anchorage open in that direction, but the internet forecast for that night and the following day had been for light south-to-southwest winds, and though we were now out of cell range, my sailor friend Jack had offered to text new forecasts each morning and evening to my handheld satellite gizmo, so we would have advance warning if the weather might change. Gone are the days of relying solely on reading the sky.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

After we positioned the boat in the center of the anchorage, Eric lowered the 8-lb anchor gently into 3′ of water just as a loon paddling close by let out its lonely oboe cry and a second loon quickly answered farther up the bay. We scanned the shoreline and saw no sign of a nest, but we guessed we had disturbed a late-spring matrimonial encounter. Indeed, when we returned to the same anchorage two weeks later, we found the loons alternately guarding and sitting on a shaggy nest built on shoreline rocks just inches above the water and hidden from above by tall grass that had sprouted on the bank.

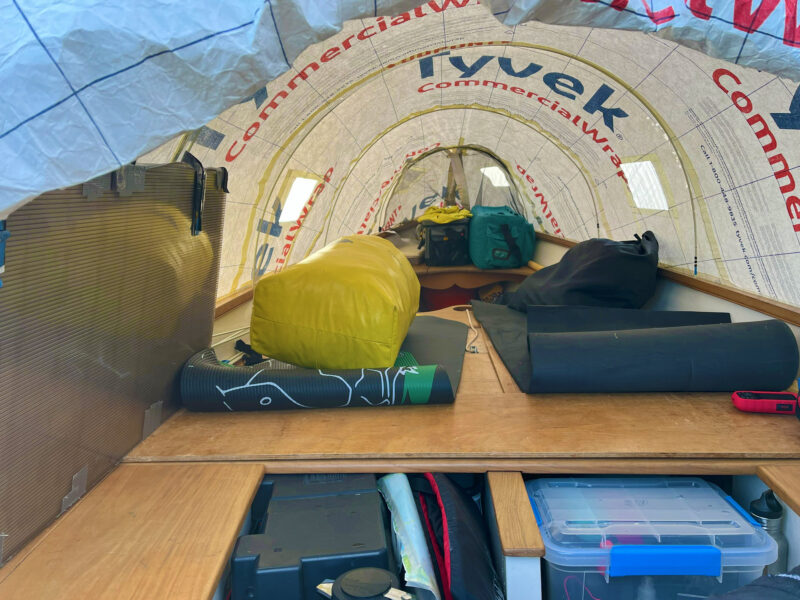

I began setting up the Conestoga-style tent I’d made of Tyvek stretched over fiberglass tent poles. The tent extends the full length of the boat, and I showed Eric how to manage the snaps and poles as I worked aft from the bow. The evening was clear and there were no bugs, so we left the cockpit open. We laid our bedrolls across the seats and plywood inserts that formed the central platform, where the 5′ 6″ beam gave us plenty of room, and then sat out in the open cockpit breathing in the fragrance of the cedar, spruce, and fir trees that nearly encircled us.

Darkness came early under the low clouds, and the temperature hovered in the low 40s, but there was not a puff of wind in the little bay. The two loons glided back and forth 25 yards off the stern, their bodies riding low in the water with only their heads, long necks, and the tops of their backs visible above the surface as their silvery wakes carved Vs into the shoreline reflections.

I heard rain on the tent sometime during the night, but it had stopped by the time I awoke at first light. I pushed away the down vest that covered my head and raised myself on one elbow to peer out the clear plastic “porthole” at the low clouds, then clambered stiffly from under my two sleeping bags. Eric’s digital thermometer read 37°F.

When we set up the Tyvek tent, we folded the two 110W solar panels and stowed them upright along the port gunwale. The “house” battery (seen lower left) doesn’t quite fit under the seat. I carried two bulky sleeping bags and other gear in the yellow dry bag. The two black yoga mats were mainly to protect our knees from the temporary plywood deck as we moved around the boat. No standing was allowed on the deck or seats while we were underway because of the potentially dire consequences of falling either into or out of the boat. For sleeping we added inflatable camping pads on top of the foam ones.

Our immediate task each morning was to make coffee. I first checked to see that the red LED light on the motor battery was glowing solid red—indicating that the battery had fully charged overnight—and then disconnected the charging cable from the house battery, plugged the electric kettle into the cigarette lighter connector, and ground fresh coffee beans in the hand mill.

Soon Eric and I had taken our positions on the aft seats—still inside the tent and comfortable enough wearing winter hats pulled down over balding heads, and winter coats pulled on over puffy down vests. We wore fingerless gloves as we each gripped a stainless-steel mug of fragrant, steaming coffee. I leaned back in the cockpit to peer out through the mosquito net at the aft end of the tent so I could get a partial view of the lake out beyond the entrance to the bay. The water there appeared to be calm, and the dark tops of the 100′-tall spruce trees stood motionless along the skyline.

We took the tent down when the air had warmed to the low 40s, but we still dawdled. Eric finally pulled the anchor late that morning—stripping the cold water from the nylon line with one hand as he laid 15′ of coils onto the teak floorboards just behind the bow seat. When the anchor reached the gunwale, he was quickly introduced to the dense, greasy clay that lies beneath the brown muck in the quiet bays of Lake Nipigon. He tried to wipe away the 3″ layer of gray clay stuck to the anchor but mostly just transferred it to his hands.

Motoring slowly out of the anchorage with no sun above us, we strained to see beneath the surface glare more than a few feet in front of the bow. The topographic maps of the lake area show land contours but little or nothing below the surface of the water, and where our map showed a rock awash outside the anchorage, we instead found a 100-yard-long reef of rock slabs and boulders that eons of winter ice had crushed and bulldozed into a level shelf just inches below the surface. I raised the motor before the prop hit anything, and we pulled out paddles. Eric paddled kneeling on the bow seat as he peered into the water in front of him, and I stood on the floorboards in the stern using a 6′-long paddle I carried for just these circumstances.

The 20’ sailing Whitehall was designed by Bruce King with a bit of rocker and a slightly cutaway stem to improve handling for recreational use. The hull is easily driven—the 3-hp electric motor pushes the hull at well over 6 knots, and paddling is an option over moderate distances. The electric motor weighs only 35 lbs, which suits the narrow stern of the Whitehall better than the much heavier weight of a comparable four-stroke engine.

Once clear of the reef, we motored along a shoreline where a bold band of black rock 3′ high had been scoured clean by waves and ice—evidence that the lake was unusually low this year. Above the band of clean rock, loose boulders, and solid bedrock were mottled with lichen of gray, pale green, and rusty orange.

To starboard, alder bushes and pale-green cedar trees 60′ high grew along the shore on shelves of dark granite. Behind them loomed much taller and darker spruce and fir with pointed tops. Close along the shore, gray-beard lichen covered the lower trunks and branches and the bleached and broken limbs that lay beneath them.

For the next two days we would meander about the Macoun Islands and west across the narrow channel to 8-mile-long Shakespeare Island. We trolled slowly in shallow waters along the island’s eastern shore and ducked into little bays and cuts to cast for brook trout over cobblestone reefs tight against the shore. When the sun came out, its warm light played off algae-covered cobbles in shallow water.

Tucked into a quiet channel between two sand beaches at midday on that first full day, with a brilliant sun overhead, we fried bacon and then blueberry pancakes on a cast-iron griddle over a propane burner set up in the cockpit. After our pancake lunch, I splashed through a quick bird bath in 45° water, stirring up the bottom muck as I hurried in and out of the shallows.

The morning at Twin Harbour was cold and threatening rain, so we opened only the bow and stern sections of the tent. We could handle the anchor, paddle to shore, and get in and out of the boat without taking the tent down entirely. The unusually low water level had exposed the bottom mud along the shore and left the flattened grass and last year’s cattails far from the water’s edge.

We anchored the first two nights at Fishhook Island, and both nights produced heavy rain, but the days were sunny and dry. The daytime air temperature held in the low to mid-40s except when we ventured across the strait to the south side of Shakespeare Island. Out in the deep, open part of the lake, water temperatures in the high 30s kept the air even colder, and the slightest breeze forced us to put on our winter hats and coats.

Once inside the protected bay of Mink Harbour on the south coast of Shakespeare, we pared down to flannel shirts and windbreakers as we alternately paddled and motored slowly over the shallows, casting here and there for pike. The soft, muddy bottom was dotted with sunken driftwood, fist-sized clams, and the dormant brown stubble of last summer’s weed growth. In the sandy shallows at the head of the bay, we came upon a cloud of reddish algae close to shore where the water had warmed.

Back out in the open lake, we paralleled the south shore under low clouds until we rounded the southwest point of Shakespeare and faced the wind as we wound our way through a scatter of small rock islets. On the wooded shore a half-mile ahead of us appeared a very large, oddly shaped, black and white object that appeared to be right on the shore. As we drew nearer, we saw that it was a freshly painted commercial fishing boat—a 40′ steel tub, looking very much self-designed and self-built, had been pulled up bow-first to the shore.

Just then we spotted a little white buoy with a faded orange flag 100 yards ahead of us. Assuming that it marked a fishing net but not knowing whether the net was strung along or across the channel, we headed straight for the buoy until we were about 10 yards from it. The lake was only a few feet deep over a sandy bottom, but the wind in our face was roiling the water such that we couldn’t see anything below the surface. We motored cautiously right up to the buoy until we could finally see a net and a series of small, half-submerged cylindrical floats strung out up the channel in front of us toward another small buoy just visible 100 yards ahead. We headed slowly north, running parallel to the mile-long series of nets.

Because of the low water level, the beaver channel in the foreground was only a few inches deep—not nearly deep enough to protect the beaver from the wolves, bears, and other predators that inhabit the area.

We stopped to fill our water jug in deep water outside a double bay we called “Twin Harbour.” Small harbors in the northland are almost always populated by beaver, which can carry giardia, so we were careful to top up our water jug before we entered. This is nature’s own water and safe to drink here and elsewhere in the Canadian North as long as one avoids drawing water near beaver lodges (and the odd uranium mine). We anchored in the north lobe of the double bay facing a low, swampy section with stunted trees that did little to block the north wind. Distinctive “beaver sticks,” stripped of bark, their ends chopped through by beaver teeth, floated near the shore, and we could see clams and a line of moose tracks in the tan mud under the boat. To windward, at the west end of a soggy beach backed by last year’s decaying cattails, a beaver channel not more than 1′ deep wound back through the grassy marsh toward a stand of alder and birch. The first few mosquitoes we had encountered buzzed around our heads as we put up the tent and, from inside, sealed the mosquito net to the transom with Velcro.

Rain was snare-drumming off the tent when we awoke the next morning. Eric reported the air temperature inside the tent was a tolerable 47°, and the fishfinder showed the water temperature in the shallow bay was 41°. The cold was not all bad as it provided great refrigeration for our fresh food supplies. I had been using powdered whole milk for coffee and cereal the last few days, but that morning I discovered a forgotten carton of milk at the bottom of the starboard seat locker—the milk was still as fresh as when I had opened the carton five days earlier. My coffee and cereal were especially good that morning.

I looked out the back of the tent and saw a bald eagle swoop down low over the marsh and pluck something big out of the water with its talons. Not until the eagle rose over the silhouette of the treetops could I see it had not captured a fish but was carrying a soggy clump of decaying reeds that swung out behind the bird as it flew low over the trees.

The day continued cold and rainy, so we passed the time under our sleeping bags napping or reading until early afternoon when the skies began to clear, and the wind dropped to 8 knots from the north-northwest. After stowing our gear and rolling the tent against the port rail, we headed out of Twin Harbour heading northwest across 6 miles of open water toward a bay called Charlie’s Harbour at the northeast end of a mainland peninsula that protrudes into the main lake.

We enjoyed a bright, cloudless sky and flat-calm water on our transit from Charlie’s Harbour through the Ursel Islands and across open water to Caribou Island, but the air was still cold enough that we wore winter coats, hats, and gloves.

Charlie’s Harbour is more than 1⁄2 mile long and 1⁄4 mile wide, opening to the north-northeast, with a generally smooth shoreline that provides little protection for a small boat. Away from shore the bay is too deep to anchor, so we pulled up very close behind a tiny sand point not far from the entrance and just 20′ off a narrow sand beach. We set one anchor right on the beach and another running perpendicular away from the shore in 6′ of water; between them they held the bow facing directly into a light north breeze.

The sky had cleared to a deep, cloudless blue, and the air had warmed, so we went ashore to explore. On the beach we found more moose tracks along with clam shells and the chalky-white scat of some animal (perhaps an otter) that seemed to have a steady diet of clams and fish.

I ducked down under the lower branches of the cedar and fir trees behind the beach. Under the dark canopy, I found the remains of some long-ago campsite whose visitors had left behind their trash. I picked a rusty can of bug spray from the tangled weeds, then a 16-oz beer can of faded blue, a plastic soda bottle, and a broken plastic pail. I stood on each in turn to flatten them, then waded out to the boat and stuffed them under my berth into the plastic shopping bag that was beginning to bulge with our own trash.

Next morning Eric and I sat in the open cockpit with our mugs of coffee as bright sunlight flooded through the tops of the trees, casting long shadows over us and out over the calm water of the bay. Small fish dimpled the surface near the beach, and four different songbirds sang their sweet melodies from unseen perches in the trees on shore—each appeared to be the sole example of its kind.

The entrance to Henry’s Harbour is protected by a rocky peninsula. We anchored in shallow water and waded ashore through the rocks and decaying remains of last year’s weed growth.

After packing up our gear and stowing the anchors in the bow, we made a smooth 12-mile passage north under sunny skies past the 200′-high rock cliffs of Grand Cape, then west through the low-lying Ursel Islands with their gently sloping sand beaches, and finally west-northwest across open water to an anchorage inside the enclosed bay at Caribou Island. The next day we fished for brook trout under sunny skies along the western shore of Caribou Island before continuing north past the black sand beaches at Champlain Point on the mainland and west across the entrance to Gull Bay toward the mile-wide and nearly circular Pike Bay.

A southwest wind was blowing 15 knots, gusting to 20, as we approached the entrance from the southeast, and the boat rolled awkwardly as waves rose and fell under the port quarter. The day was sunny, though, and I thought the generally shallow, sandy Pike Bay would be a good place to practice using the emergency mast and sail that I carried to provide one way of getting back to the boat ramp if the motor conked out. The Whitehall has a full sailing rig, rudder, and tiller, but it’s too much to carry as backup on a solar-powered motor cruise. Instead, we carried only the jib—complete with wire forestay, halyard, and sheets.

On a wilderness trip several years ago, my son and I had cut and rudely shaped a small pine tree and stepped it as a full-length mast to which we set the jib vertically in its normal position. On this trip, however, I carried an 8′ × 1 5⁄16″ laminated wood dowel I had picked up at a hardware store to act as a short mast for the jib, which would be set upside-down. The tack of the sail would be set at the bow where it usually is, but the head of the sail would be pulled aft along the rail with the halyard attached to act as the sheet. The clew of the sail would be hauled up by one of the attached sheets to the top of the makeshift mast. The 8′ dowel was fitted-out with a few odds and ends to make it fit somewhat snugly in the partner and step meant for the spruce mast. I had tried out this same rig with great success while on a solo trip to Nipigon the previous year. The wind had been strong that day, too, and the boat had fairly skimmed along at 3.5 mph on a broad reach. I expected to fare as well in Pike Bay.

With the wind blowing strongly into the bay from the southwest, we stopped to assemble the rig in calm water close in the lee of a small island that sat in the middle of the entrance. From there, I planned to sail on a broad reach along the south shore of the bay in the lee of a long, low peninsula, where we would be protected from the strongest wind and waves.

In 2023, when this picture was taken, I tested the upside-down jib as auxiliary power on a solo trip to Lake Nipigon. I rigged it using one of the sheets as the halyard and the other cleated down to port as a backstay. When Eric and I tried the same rig this year in Pike Bay, I forgot to rig the backstay and the dowel mast snapped.

I lowered the centerboard several inches and raised the sail, but we didn’t move, so I paddled a few strokes. Edging forward out of the lee, the sail filled with the wind on the port quarter, but the boat was sluggish with all the weight she carried. When we finally ghosted out of the lee and headed into the bay, powerful gusts hit the boat.

I sat in the starboard quarter holding the sheet taut in my left hand as my right hand gripped the handle of a paddle that I levered against the side of the boat to help steer. The mast bowed more and more with each gust. The boat was just beginning to plow through the whitecaps when an especially strong gust hit the sail. The dowel bowed ominously and then snapped with a loud crack, and the sail tumbled over the side. I had forgotten to cleat the second jibsheet down as a running backstay!

With no harm done other than a broken dowel, we had a good laugh, quickly stowed everything, and motored across the turbid shallows of the bay to a broad river mouth at the southwest shore. We set out two anchors, port and starboard, to hold the boat between little flat islands ringed with water reeds and topped with cattails.

The first blackflies of the season discovered us there the following morning. It was the first day of June, the wind had died, the sun was bright and very warm, and we had stripped down to T-shirts and long pants. The water in the river mouth was already too warm to hold fish, so we motored out of Pike Bay heading northeast into the cold, deep, open part of the lake.

A 10-mile passage carried us to the western end of Kelvin Island where we anchored off a marsh deep at the head of a bay identified as Henry’s Harbour on the topo map. Our hope in visiting Henry’s Harbour was to see a moose in the large marsh and alder thickets that fill the head of the bay, and as we anchored the boat, we could see tracks the size of soup plates crisscrossing the muck below.

Eric soon spotted a moose walking chest deep through the water just 200 yards away. We quickly pulled the anchor and began motoring slowly at an oblique angle that we hoped would get us closer to the moose without spooking it. The moose just craned its lumpy, antlerless head with its donkey ears, looked over its shoulder at us for a moment, and then turned to resume its leisurely walk toward shore—lifting one bony leg after another half out of the water as it splashed slowly forward. We approached closer but were still 80 yards away when the moose gathered pace and, with more purpose, trundled off to the shore, lurched up the bank, and turned amid the cattail stalks to look directly at us before turning back and cantering away into the alder thicket.

From Henry’s Harbour, we traveled north under sunny skies and light winds along the northwest coast of Kelvin Island, around the island’s northern point, then southeast and finally south into a half-mile-wide bay called Moose’s Harbour on the eastern side of Kelvin. We searched the entire circumference of Moose’s Harbour for a protected place to anchor a small boat but found nothing suitable.

With darkness coming on and clouds and bad weather moving in, we motored around the point that formed the eastern shore of the bay to a tiny, round cove that opened through a narrow, dog-leg channel to the main lake. We called the anchorage “Sock Harbour” because of its shape. At its toe, the little cove was only 50 yards wide and 2′ deep with a marsh at its northwestern end and rock ledges topped by cedar trees opening to the crooked channel on its eastern side.

Having used most of our battery capacity on the foggy transit from Kelvin Island to Shakespeare Island, Eric checked the flow of amps that evening to see if it was worth leaving the solar panels deployed a little longer.

Rain began drumming on the Tyvek tent late that night and didn’t stop until the following afternoon. The clouds finally cleared in the evening, but we awoke early the next morning in a dense fog; the tent was wet inside and out from condensation. We hurried through our morning routine and set out through the fog heading for the northwest corner of Shakespeare Island—15 miles to the south.

The lake was glassy calm. The only sound at our stern was the prop churning quietly under the transom, and the Whitehall left virtually no wake. The only sound forward came from a 2″ bow wave that gurgled softly as it passed along the hull. Fog lay on the horizon all around us, and the dark mass of Kelvin Island was barely visible half a mile to starboard, but the sky was bright blue above us and to the north. As we cleared the southernmost point, a white fogbow appeared where the sun shone directly into the haze—the glowing band of white light arching over the water like half a smoke ring until its two ends plunged into the cold water.

Eric and I were comfortable in our coats and hats as we motored along at an efficient 3.6 mph to save battery power on the long crossing, but the air registered only 47°, and the surface water temperature was only 39° over 283′ of deep blue. As Kelvin Island disappeared in the fog behind us, we could see nothing to steer by but the compass. We heard no sounds, saw no wakes from distant boats: no one was out there but the two of us.

A lone gull cried overhead as Shakespeare Island finally came into view through the fog. Ravens cawed from a wooded island somewhere off the port bow as we approached the entrance to a crooked bay we called “The Hook” on the northwestern corner of Shakespeare. After inspecting the anchorage, we moved back outside to cast for brook trout over rocky shoals at the mouth of the bay—twice running straight up on boulders hidden beneath the reflected glare of the sun. Striking more rocks than fish, we soon nosed the boat onto a gray sand beach, unfolded the solar panels on deck to charge the house battery, and set an anchor in the dry sand of the beach.

We spent our last two nights anchored at Fishhook Island where the bay is protected in all directions except through the narrow entrance channel to the northwest. In the foreground is a “beaver stick” (in this case, an alder branch) with its bark eaten away to reveal the white sapwood beneath.

On the 15th day of our trip, we returned to our first anchorage at Fishhook Island having traversed 165 miles around the lower half of Lake Nipigon. We were trolling slowly southward toward the island in a flat calm when suddenly a strong puff of cold air at our backs presaged the approach of weather from the north. We continued trolling all the way to the island and carefully avoided the rock shoal, barely detectable as a slight browning of the water’s color on the south side of the entrance. A northwest wind of 8 to 10 knots was blowing directly into the cove, so we tucked into a little V-shaped notch at the northeast corner and put out two anchors on tight lines from the bow with our stern 10 yards from shore and the keel floating just 2″ above the mud bottom.

That evening we cooked dinner in the open cockpit with the tent protecting the propane stove from the wind as we watched luminous, silky-smooth cumulus clouds build over the western horizon. No rain threatened, so we sat outside until 9:30 when the sun finally dropped behind the clouds, quickly chilling the air. An undisciplined chorus of little frogs peeped from the nearby marsh, and our two loons called their oboe-like notes to each other from across the cove. Two new loons dropped down to the relatively calm water of the outer cove but soon departed—taxiing away down the channel with their wings flapping and their webbed feet slapping the water loudly until they finally gained enough speed and altitude to fly. For a moment, a tiny flash of sunlight reflected off their wet backs as they disappeared across the lake.

The night soon turned blustery with rain and 20-mph winds. On shore, the dark forms of spruce and fir trees swayed in the wind—each to its own rhythm—but with two anchors set on opposite sides of the bow, we pointed neatly into the wind, and the boat sat nearly motionless as 1″ to 2″ wavelets passed along the hull.

The wind came up from the northwest on our last night at Fishhook Island, so we tucked in very close to shore in a tiny cove where a low, rocky point protected us from the waves but not the wind.

Our final morning on the lake dawned cold and calm. We needed a favorable wind for our 10-mile run across the open lake to High Hill Harbour. My friend Jack texted the forecast from his house in Maine as we sat in the shelter of our tent. The early morning would likely be dry and partly cloudy with a light southwest breeze building to 20 knots after midday. It was a call to action; we heated coffee water in the electric kettle and began packing our gear quickly inside the tent as patches of blue sky appeared through the portholes.

Soon out on the open lake, we headed east-northeast toward High Hill Harbour, which lay unseen below the eastern horizon, our bow parting a heavy dusting of tree pollen that covered the surface of the lake and left yellow swirls in our wake. A line of rain squalls was developing over the mainland to the southwest and appeared to be moving northeast to intersect our course. Another line of squalls appeared on the horizon to the northwest and another over the mainland to the northeast. I checked the charge indicator on the motor battery and turned the throttle up until we were skimming along at 6 mph, trying to beat the showers.

Halfway to High Hill Harbour, we could just make out the shapes of two cell towers standing atop a darkly forested ridge in the direction of the outpost town of Beardmore and the highway that would take us away from the lake. We were almost there, and the modern world was waiting… Neither of us reached for our phone.![]()

Tim O’Meara grew up sailing and otherwise mucking about in small wooden boats on Lake Okoboji in northern Iowa during the 1950s and ’60s. In college he was fortunate to sail 30′ sloops on San Francisco Bay as a junior member of a club team, and during two summer breaks crewed on a wooden 50′ Rhodes cutter off the California coast and then around the Hawaiian Islands and back to San Francisco. After graduating in 1970, he set off with two friends and a brother and sailed around the Caribbean for a year in an aging fiberglass sloop. A lost year soon followed during which Tim built a cold-molded version of the tender for Herreshoff’s yacht COLUMBIA; the tender now hangs in his garage above the 20′ Whitehall. Three graduate degrees in archaeology and anthropology were followed by 13 years of teaching at universities in the United States and Australia and then 25 years working as a consultant on economic development projects focused on the Pacific Islands where he learned to sail traditional wood canoes: in 1973 on the island of Taha’a in the Leeward Society Islands, and in 1988 and again in 1993 on Ifaluk Atoll in the Western Caroline Islands. Tim is now retired and spending as much time on the water as possible. He described an earlier voyage in his 20′ Whitehall in “An Electric Journey to Knight Inlet.”

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

I really enjoyed this article. Would have loved a few more pictures, especially of tent and sleeping arrangements.

It must have been a magical trip.

Thanks, Cliff. Yes, we had a great trip on a gorgeous lake. The tent is Tyvek CommercialWrap, which is UV resistant and 50% thicker than HomeWrap. The seams are taped with 3M double-sided tape, which is also UV resistant. The poles are 1/4″ fiberglass. The “portholes” are cut from heavy plastic freezer bags and taped in place with the 3M tape. Mosquito net fore and aft has duct tape around the edges for reinforcement and then taped (fore) or Velcro-ed (aft) in place. The fore section of the Tyvek and the underlying mosquito net both have Velcro seams up the center to allow access to the anchor. Sitting height in the center of the tent is approx 45″ (from memory), which is several inches above sitting head height. I kept the height fairly low to reduce windage in summer thunderstorms. Over the preceding 30 years (two boats and three Tyvek tents), I have experienced thunderstorm wind speeds over 50 mph at anchor on three occasions — pretty exciting but no issues at all with the tents.

Reading your story full of wonders, found myself hungering for more details…

1) Why, do you figure, when you apparently undid the house battery’s terminal bolts, and removed the cigarette lighter, and then redid the battery terminal bolts, did the house battery once again resume charging the motor battery?

2) How many amp hours each were your house battery and motor battery?

3) What brand/make electric motor did you use?

4) During the trip, were you able to have a fair idea of how many amp hours you were using per day, versus how many you were able to recharge your batteries?

Thanks, Cliff. Yes, we had a great trip on a gorgeous lake. The tent is Tyvek CommercialWrap, which is UV resistant and 50% thicker than HomeWrap. The seams are taped with 3M double-sided tape, which is also UV resistant. The poles are 1/4″ fiberglass. The “portholes” are cut from heavy plastic freezer bags and taped in place with the 3M tape. Mosquito net fore and aft has duct tape around the edges for reinforcement and then taped (fore) or Velcro-ed (aft) in place. The fore section of the Tyvek and the underlying mosquito net both have Velcro seams up the center to allow access to the anchor. Sitting height in the center of the tent is approx 45″ (from memory), which is several inches above sitting head height. I kept the height fairly low to reduce windage in summer thunderstorms. Over the preceding 30 years (two boats and three Tyvek tents), I have experienced thunderstorm wind speeds over 50 mph at anchor on three occasions — pretty exciting but no issues at all with the tents.