When my wife and I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, I felt I had arrived in paradise: mild weather, great food, plenty to do in the glorious outdoors. But when I became a father in the Bay Area, I began to wonder if paradise might be a challenging place to raise well-rounded adults. For one thing: how would our children learn patience, perseverance, independence, and resilience without challenges like the truly awful summers of my youth in California’s Central Valley? I remembered a fellow teenage camper on a hike in the Marble Mountains who collapsed mid-hike under a not-that-heavy backpack, wailing that the 80° heat was too much for him as he was “from Marin County.” I didn’t want to intentionally subject my kids to suffering, but I didn’t want them to have it too easy, either.

What was needed was a mildly demanding system of real rewards and consequences, accessible to very young participants; a way to introduce incidental hardship in the guise of pure fun. What was needed was a boat.

Thomas Schwei

Thomas Schwei“Fair winds, following seas, and safe returns!” It had been a few years since we last sprayed champagne, and our skills had suffered from disuse. But TOTORO was launched, most of the bubbly got on the boat, and the supervisor was none the worse for the sprinkling.

We chose François Vivier’s Seil, an 18′ sail-and-oar cruiser. As best I could tell, it would be the right compromise: large enough for the four of us, small enough to be rowed by one person; stable and forgiving, but capable of thrilling sail performance; and plenty of storage room for gear, without sacrificing carefully designed and tested built-in flotation along with the ability to self-rescue after a capsize. I anticipated that the build would take at least three years so, wanting to occupy the smallest possible footprint for as long as possible, I began not with the hull but with all the rest: the sails, spars, oars, and foils.

I started when our younger boy was seven months old, young enough to watch me shape oars with chisels and hand planes for an hour without demanding much beyond the occasional ash shaving to chew. His way of thoughtfully overseeing fit so nicely into the home workshop that we took to calling him the “supervisor.”

His older brother was then three, old enough to come to the project with ideas of his own and a passionate commitment to directing his father’s efforts. He quickly earned the title “manager,” and when, after a few weeks of intermittent work sewing the sail, he stopped calling it “Dada’s sailboat” and started calling it “our sailboat,” I felt we already had our money’s worth.

Forty friends and family came to the naming party, and the boys showed every one of them the many parts they had built. Their descriptions of smoothing the hull led their grandfather to declare them “boat sanders, first class.” He still occasionally calls them this, even in unrelated landlocked gatherings, where the title confuses everyone else but pinks his grandsons’ cheeks with pride.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorIn our first summer we quickly came to appreciate TOTORO’s size—large enough for each boy to have a space of his own, even when we were loaded for camping. A small deeply curved section in the bow cradled the manager at all angles of heel until he lost his fear of the leaning boat. Airtight buoyancy compartments under the side benches held up to five sleeping bags, most of our sleeping mats, and warm dry clothing for us all.

We named the boat TOTORO after the eponymous forest spirit of Hayao Miyazaki’s 1988 animated film, My Neighbor Totoro. We can’t agree on how we came to it—everyone is pretty sure someone else said it first—but we all agree it fits. The cinematic Totoro is a powerful, gentle, protective creature, visible only to the very young, useful in a crisis if you can rouse him, but preferring to spend his day napping in the dappled sunshine nestled in a bed of wildflowers. What more could we want?

In that first summer, TOTORO proved more able and better suited to our needs than we had dared hope. We camped for weeks in lovely, quiet spots accessible only from the water. The boys, by then three and six years old, loved riding in the boat and were loosely interested in its workings, but didn’t seek further responsibility. I’d suggest that the manager might like to helm, and he’d agreeably hold the tiller, but I couldn’t convince him to keep his eyes out of the boat and off his book. They were delighted to be out there, but a bit surprised when any action, like crossing the boat in a tack, was required. We figured they’d come to it when they were ready.

By the next summer, the manager was ready.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

"Wow Dad. Even you got enough boating today.”

The manager and I were finally settled in for the evening. Vegan sausages sizzled over a beach fire as wind blew through the cottonwood trees above our tent. The Sacramento River loped by, strong and loud, the exact color of school-lunch chocolate milk. Bats pirouetted in the remains of a sherbet sunset; herons winged overhead, every bit as sharply shaped as their pterodactyl ancestors; everything was going somewhere and doing something fast except, finally, us. The growing dark and glowing embers and promise of many roasted marshmallows to come lit the manager’s face, not too badly burned by our long day under the sun. With 20 miles of river covered through a wicked headwind, there hadn’t been much time to unwind.

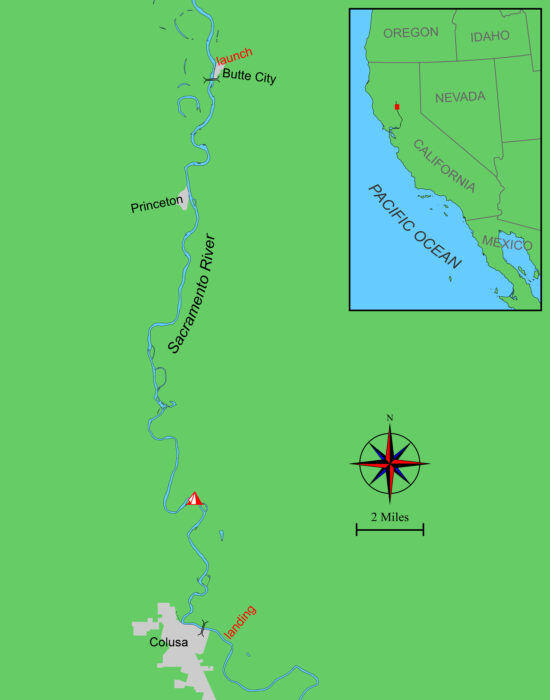

That morning, the manager and I had launched TOTORO on the river in Butte City, where dusty façades hinted at a past that must have seemed destined for a more expansive future. A store grandly called the Butte City Emporium stood vacated, red-tagged, and barred. The only saloon in town had burned to its foundation years ago, and now there wasn’t even a place for a seven-year-old and his dad to pick up a cold soda and some local conversation. I guessed that, like a lot of valley towns, Butte City’s heyday coincided with the peak of commercial transport on the Sacramento River, when there were livings to be made in the places where farm goods met barges. Now, about all that remained was a good county boat ramp and a not-too-dangerously-rotten dock.

We encountered our first hazard almost as soon as we left Butte City. I looked downstream with mild trepidation; the manager was unmoved.

Our plan was to ride the river south from Butte City to Colusa, where we would meet my wife and the supervisor the next morning. We knew next to nothing about the river. I hoped it would give us a view into the backyards and remaining wild spaces of a landscape that showed none of its secrets to the straight-line highways we usually traveled. We took advantage of a large family vacation and arranged a car shuttle to allow a one-way float downstream—freeing us, I hoped, of any real need for the motor we didn’t have. Our local extended family said that while they’d never heard of anyone sailing this stretch of the Sacramento, we couldn’t go too far wrong. It was mid-May; snow melting in the mountains would make for high river flow. Anything floating in the stream would move along at 2 or 3 knots. The estimate was reinforced by an excellent, though perhaps dated, float-time map published by the California State Parks service, which suggested, by dint of its existence, that a non-motorized boat might not be a bad way to see the Sacramento River.

The momentum provided by the current was important. This would be the longest boat journey the manager had ever taken. We had carefully eased the boys into onboard life via short, sweet jaunts, with plenty of distractions in the boat, plenty of food, and plenty of stops ashore. Now the manager and I were launching into a current too strong to row against and aiming for a destination far downstream; it was a commitment to a considerably greater journey. The manager’s frequent natural wish for variety would have to be weighed against a real need to cover river miles. He’d be asked to practice patience all day long.

We set off with the rig down and, minutes later, came to three tightly spaced bridges, really three iterations of the same bridge: one antiquated, one currently in use, and one under construction. If there had been time or space I would have mused aloud on the role of the bridges, roads, and rails in changing the local economy and demographics of the valley towns, their past, present, and future. We were spared the lecture by the need to find and transit a tight gap in the bridge construction. We looked up at cranes laying steel, and workers grinding and welding, then ahead at the current swirling up around closely spaced pilings, and I wondered, briefly, what I had signed us up for. Then we were through, clearing the clamor with room to spare, my doubts left behind.

The family tent is so large and heavy that its storage bag has built-in backpack straps. Lashed against the side of the boat, it provided a good backrest for a devoted reader. The manager required a quantity of books roughly equal to his own weight, but the payoff (a happily occupied crew) was entirely worth it.

Beyond the bridges, I shipped the oars. The Sacramento River lay broad and silty under the spring sun, braiding through a shallow, wide, gravelly cut in the vast working plain. Row crops and orchards abutted the banks. It was only May, and we’d had a rare wet winter, yet already everything once green had turned to tan, another shade on the continuum of browns that encompassed our surroundings: dirty clay banks, dried dead grasses, dust clouds raised by tractors and the gusty wind, the river itself, and with time under this sun, our own tanned arms and faces. Already visible downstream were the rising riparian jungles we had come to explore—ahead lay green.

With no independent movement over the water, TOTORO spun slowly in the current, nosing at times into swift sinews of brown water on the outside of the river bends, drifting at others with the wind into slower eddies. We needed some kind of speed to maintain steerage, but I was the boat’s primary engine and was feeling lazy, under-caffeinated, and disinclined to row.

“If only we could have launched yesterday,” I said. “We would have had a tailwind that just wouldn’t quit.”

“You could have taken me out of school yesterday!” came the swift reply. “That would have been fine.”

“Well, we could sail now. We’d just need to tack often.”

“That sounds OK.”

“The wind is strong. I’ll tuck in two reefs, but the boat will still heel. Is that OK?”

“Um… OK? I don’t know.”

“Well let’s try it. You can always tell me if you don’t like it.”

With two reefs, a 3-knot current behind, and a headwind gusting in the low 20s, TOTORO picked up her skirts and ran for the riverbank. If we were to sail in these conditions I was going to have to learn a lot of river piloting very quickly.

Hot, Hot, HOT! We tucked into a back eddy around the downriver tip of an island to sample life ashore, but the sunbaked sand was too hot to stand on barefoot. We didn’t linger, but soon pushed off in search of new landings.

Jerry MacMullen, historian of Sacramento River paddle-wheel steamers, wrote “River seamanship is an art in itself, and any of the salt-water brethren who are inclined to look down their noses at river pilots are invited to try it themselves sometime, preferably with a vessel of no great value. The river pilot must know all the answers, and know them right now.”

That afternoon I had none of the answers, but I slowly gained confidence in my guesses. Rarely more than 600′ wide and seemingly never configured the same way twice, the river required constant tacking and provided endless variation. Some courses were threatened by shallows and visible riffles; some by downed trees straining in the fast-moving water; some by long branches dangling overhead, sticky traps ready to grab our mast. Deciding where to point the boat, guessing where the sum of the variable current and TOTORO’s own movement would take us, hedging against the unpredictable blows that came tearing through the trees at the worst times, and recognizing the last moment in which to tack safely: this was to be my all-consuming work for the afternoon. The alternative was to take ignominiously to the oars.

The manager was an excellent crew. He kept himself shaded from the hot sun, properly fed, and well watered. He exercised TOTORO’s library, working through most of the collected comic strips of Calvin and Hobbes and a good deal of the Dog Man oeuvre. His initial hesitance about the heeling boat was relieved when I showed him how quickly we popped upright with an eased mainsheet, and how the sheet was always in my hand. He asked for—and mostly got—many stops to explore the sandbanks and islands that dotted the banks every mile or so, and was perfectly understanding when we had to press on.

From time to time the wind would ease off and the reef seemed excessive, but then we would round a bend and be hit by another gust, and I was glad I’d not been tempted to shake it out.

My pre-trip investigation of the route had shown me that there really were no opportunities for getting lost: so long as the water beneath us was moving, we were in the right place. So, we hardly looked at the few charts we had brought. At any given moment we were somewhere between Butte City and Colusa, just as we had been all day, and just as we would be until tomorrow morning’s rendezvous. I wondered if not knowing our precise location made it easier for us to enjoy being there and not fuss about what came next. Lying on hot sand for a brief bit of relaxation in the mid-afternoon, we traced verdant wild grape vines far up into the tops of tall overhanging cottonwoods and oaks. Dense willow, poison oak, and thorny blackberries formed a foreboding understory. We agreed we had lucked into the right way to see and transit the river jungle.

Late afternoon found us still sailing, tired but proud, a hundred successful tacks behind us and not a scratch on the boat. We approached an aluminum outboard fishing boat, anchored midstream with a crew of two retirement-aged men. We saw our own novelty—and perhaps the beauty of our boat—reflected in the slow back-and-forth motion of their white beards, white hair, and dark visors as they followed our tacks down the river toward them. We must have been quite a sight racing back and forth, our pale green hull contrasting with the muddy stream, the cream-colored sail above stark against a cloudless valley sky.

As I put in a final insouciant tack to pass upstream of the fishermen, their countenances changed from passive admiration to active concern. I registered their feeling but did not share it. Could they really think we would hit them? I enjoyed a moment of bemused condescension—motorboaters, no possible sense of the glory of sailing—before my error became clear even to me. We were about to collide. I threw us into a tack and shouted at the manager far forward in the bow.

Large cottonwoods, like these, have a reputation for losing limbs in high winds. The tent site, to windward of the trees, seemed safe enough when we wanted shade, but not quite so risk-free when I was lying awake in the night listening to the wind.

“Get down and stay low!”

“Got it! Down and low!”

The tack was too late: the current, relentless as ever, brought us down on their sharp metal bow. I sprang forward just in time to fend off, narrowly dodging hull-to-hull contact.

“I am so sorry! This is my fault,” I cried out, as though our victims had not personally witnessed my very recent and very obvious stupidity, and as though we were not near enough to shake hands. They responded with remarkable kindness.

“Well! That big sail must really catch the wind. It pushes you around.”

“No!” I hollered, adding absurd denial to my sins. “We were doing great before. I am so sorry. My fault.”

We drifted apart, undamaged, to the sound of four relieved sighs. Better, perhaps, to be lucky than good. The manager picked himself up from the floorboards, dusted himself off, and reached for a book.

I was about to offer the fishermen a compensatory beer at some downstream bar when, hearing a new zinging sound, we all turned to see several of their fishing lines dragging loudly across TOTORO’s mast. Thick fishing lines, ending no doubt in large, sharp hooks. We were gathering them up rapidly as the boats diverged in the current.

Even in my fear I felt glowing pride at the speed with which the manager again dropped to the bottom of the boat, repeating “Down and low!” as he went. When the hooks, sharp and finger-sized, finally came aboard and snagged the mast at the thwart he was safely away aft. The lines stretched and snapped, and we were free. The poor fishermen’s hooks, now firmly embedded in the leather of the mastgate, came downriver with us.

I grabbed the tiller and the sheet and got us pointed back downstream. Without comment, the manager returned to his book, as though there was nothing unusual about ramming boats that were in our way. The fishermen receded upriver and into the past, their white beards and dark visors again gently swaying side-to-side, perhaps no longer tracking our course but simply shaking their heads at the follies of youth.

François Vivier’s description of the Seil notes that the “fore rocking facilitates embarking on the strand.” I read that comment at least five times and thought I understood, but I only fully appreciated it the first time I sent a child forward alone to step over the transom bow and onto dry land. TOTORO’s weighted centerboard, kick-up rudder, and shallow draft make beaching effortless—a good feature for a restless crew.

The approaching riverbank demanded a tack. I went for it, and botched it, audibly skidding the centerboard over gravel. Self-doubt set in, and for the rest of the afternoon I could do nothing right.

Later that evening, camped under the cottonwoods next to the river, our appetites whetted by the smell of a fire-roasting dinner, our heads filled with memories of a long day afloat, the manager kindly said that he thought we had picked a great campsite and built a great fire. I told him how impressed I was by his quick reflexes during the crash: no questions, no backtalk, just great reactions. All-day patience practice had become all-day sailing practice had become a lesson in paternal humility, or perhaps paternal hypocrisy. I gazed into the embers and told my son of a long-ago family road trip across the desert when my father and cousin, two self-reported terrific drivers, pulled into a turnout to confer, and slowly crashed their cars into each other. I can still remember the sound of squealing metal. Our car wore the dents for the rest of my youth. If I had done it, I told the manager, “there would have been hell to pay, but fathers are good at forgiving themselves for sins they’d crucify their sons for.”

The best s’mores, we decided, require strategy, preparation, and intense focus.

“Like getting sand in food?” the manager asked.

“I suppose so. Why?”

“You just dropped a sausage on the beach. It looks gross now.”

“Oh, indeed. I have already forgiven myself. Ready for dinner?”

“Yes. I’ll take the other sausage, please.”

We made one final landfall before our arrival in Colusa. One of my favorite features of the unstayed lug is how easily it can be dropped—a great safety feature and one that eases the fears of a hesitant crew. On the second morning I dropped and packed up the rig before setting out both to reduce windage and make rowing easier, and in preparation for the end of our trip.

The morning smelled of damp reeds and river mud. We had packed minimally, eschewing a stove in favor of last night’s fire, meaning there could be no cooking our usual breakfasts. Instead, we ate oats and raisins soaked overnight in milk we had kept chilled in a thermos. The taste was far superior, we agreed, to gluey cooked oatmeal, and surely a recipe to repeat all summer. When we broke camp, I noticed that for the first time the manager did not need to be asked to haul gear toward the boat.

We shoved off into less wind, easy rowing, and steeper, riprap-lined channels along much of the bank. A short distance downstream on the right bank was a wide nature reserve. Much of it had recently burned, and fire scars ran sometimes close to the low bank, leaving gaunt standing snags. It was dark and eerie under an unseasonably overcast sky.

TOTORO lay alongside at Colusa landing for a few days before we returned with the trailer to retrieve her.

On a bend, as we approached the outskirts of Colusa, we pulled in for one last beach stop and then set off to find the marina by 11 a.m., the appointed hour. We rowed a very slow 100′ upstream along a finger dock to tie up in our reserved space, paid for the few days of dock fees we’d accumulate before we could return to pick up TOTORO, and hauled our gear to the parking lot, just in time for the arrival of my wife and the supervisor, and a joyful reunion. The manager was proud to tell his mother of our feats on the water. I smiled; he had come away from the river a little taller and a little surer than he had come to it.

Weeks later, the manager, the supervisor, and I found ourselves afloat on Spicer Meadows Reservoir, a big blue drop among bone-white granite at 6,600′ in the Sierra Nevada mountains. A brisk upwind sail had occasioned discussion of the term “rail meat,” initially received as an affront but eventually understood as praise of the nimble and accurate movement executed by both boys in every tack. As we arrived at the limit of their patience with the role of movable ballast, I rounded up, dropped the yard, and tentatively suggested that the manager might enjoy sailing us under bare poles back to our friends at the campsite.

The manager—a steady and reliable hand.

He sat up and looked downwind. “You mean that big cliff way down there with the tallest trees on top? I’ll take us right to it!” Sure enough: eyes out of the boat, head on a swivel, arm comfortably over the tiller, no distracting book at hand, he held his course to the right true line. Last summer’s awkward crew had become this year’s reliable hand.![]()

James Kealey is a teacher and avid outdoorsman living in Richmond, California. TOTORO is the second boat he has built; he profiled his first build, a Gentry Shenandoah Whitehall, for this magazine.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Thanks for sharing a lovely story, James, a lovely boat, and a lovely family.

What a wonderful story!

Your boys are lucky to have you as their dad.

I built an Ilur back in 2016-17 (see below). After many weeks of deliberation between various hues of green, I picked for Clarisa’s hull what appears to be the identical color as you have on your beautiful Seil. It was a custom color that was mixed for me by Kirby Paints. It was called “Olive-Martini”. Did you buy your paint from Kirby?

Thanks again!

Thanks for the kind words, Christoph. TOTORO’s exterior paint is Benjamin Moore 429, Garland Green. The match with Clarisa appears to be pure chance. Or maybe convergent evolution. I love the color but can take no credit for it as my wife picked it. I am quite colorblind and have learned to leave these choices to her. My only input was that I liked the Celeste green of Bianchi bikes but wanted something a bit warmer.

I think that Olive-Martini is a better name!