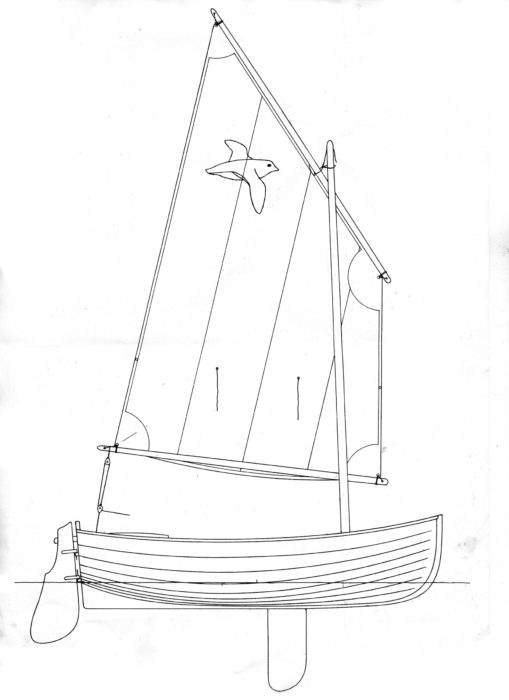

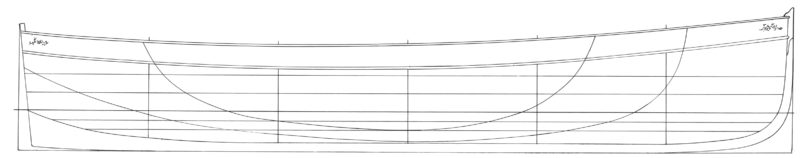

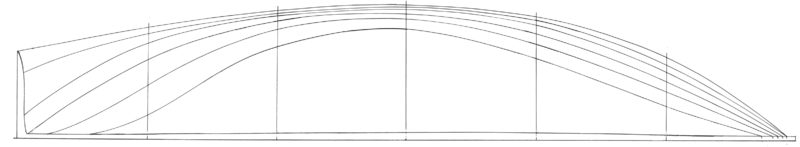

The Auk is an Iain Oughtred design that dates back to 1984. He was “just looking at traditional boats and trying to produce an ideal version of an 8′ tender.” It was a smaller version of the Puffin, a 10′ tender he had previously designed; he gave the Auk a generous beam for its length and a particularly pronounced sheer. “I tend to agree with Uffa Fox that you should have a good strong sheer because it is stylish and it helps keep the water out,” he said. After selling about 250 sets of Auk plans, he redesigned it about 10 years ago to be “a refined version of the same thing with a couple of inches more beam,” and has sold a further 116 sets of plans since then. It is designed primarily as a tender with carrying capacity of three or four people “in sensible conditions,” but he gave it a balanced lug rig for sailing.

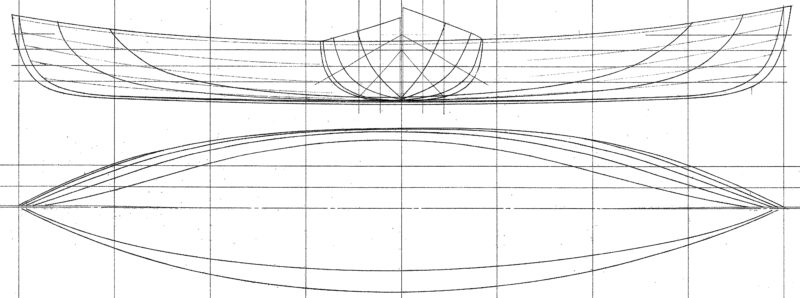

When Sam Manners enrolled at the Boat Building Academy in Lyme Regis, England, he decided he would like to build an Auk, but was keen for his to be a bit longer. Iain offers two lengths for the Auk with a little stretching by spacing the five molds, transom, and stem 2″ farther apart to increase the length of the Auk from 7′11″ to 8′11″, but Sam wanted to go a bit longer. He decided to space them 2-1/2″ farther apart than designed, which would give him an overall length of 9′2″.

Sam Manners

Sam MannersThe interior is functional, uncluttered, and easy to clean and maintain.

Printed plans include 12 pages consisting of an introduction, four pages giving basic knowledge regarding traditional and glued clinker construction, the table of offsets, and templates for the full-scale half molds. The plans are not available digitally.

“However good the plans and templates are, we always advocate lofting,” said course tutor Mike Broome, “as it allows any errors on the designer’s part to become apparent. Also, if you are stretching the boat, it’s the only way to get it all faired up. It also means you can lift patterns and templates for any elements of the fit-out, etc.”

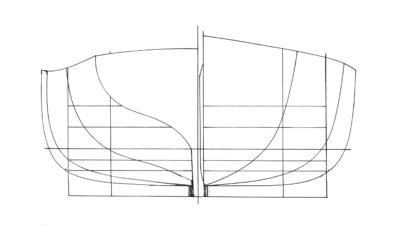

After lofting the lines full-size, he and fellow students set to work by setting up five 1/2″ plywood temporary molds and the 7/8″-thick khaya transom upside down on a low workbench to give a comfortable working height. The centerline structure was then added. This consisted of the sapele hog 3/4″ thick and 3-1/4″ wide to allow for the daggerboard slot, although for the rowing-only version noted in the plans it would only be 2-3/4″ wide. The aft end of the hog had to be steamed to cope with the rocker. The curved inner stem (or apron) was laminated from nine layers of 1/8″-thick sapele.

The planks are 1/4″ BS1088 sapele plywood. The garboards were laid over the hog, meeting each other in the middle and glued with epoxy. The rest of the planking was epoxied along the 3/4″-wide laps using shop-made planking clamps known as “gripes,” and temporary screws at the hood ends to hold everything in place while the glue set.

Nigel Sharp

Nigel SharpThe standard arrangement for sailing is a balanced lug sail with a daggerboard. The plans offer another option: a standing lug with a leeboard.

The plans called for eight strakes, and that is what Sam and his fellow students fitted, but they had trouble fitting the planks around the turn of the bilge. There were two planks on each side that had get around nearly 90 degrees. “It took many attempts, and we probably got through a full sheet of plywood just trying to get that curve,” Sam said, “but we managed to get it eventually with the aid of double the number of gripes. If I built another one I think I would fit three planks round that curve.”

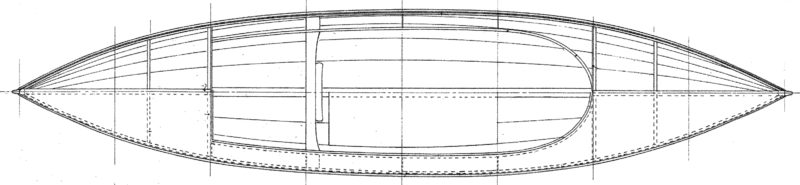

Once the planking was completed, a 1″-thick sapele skeg and keel were fitted as well as a pair of 2′ x 3/4″-square bilge runners, followed by the outer stem (made up from three pieces of sapele scarfed together) which sealed the end grain of the plywood planks at the bow. The daggerboard slot was cut through the centerline. An epoxy sealant followed by epoxy primer were then applied to the outside of the hull.

When the hull was flipped upright and the temporary molds were removed, it “wobbled like jelly,” but before any stiffening structure was fitted, the excess epoxy was scraped away and the inside of the hull was sanded. Once that somewhat laborious process was completed, four 3/4″-thick sapele floors were fitted.

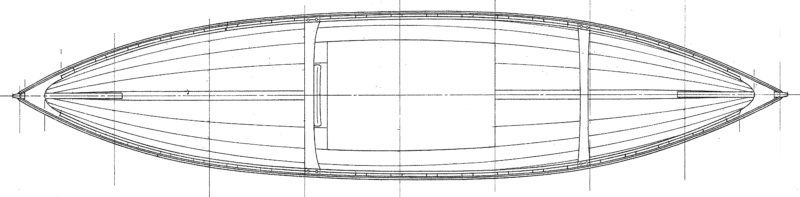

The daggerboard case is made of ¼” plywood stiffened by a 2″ x ¾″ khaya framework and braced with the 7/8″-thick khaya center thwart. Rather than having continuous risers, the forward and central thwarts bear on short supports, while the stern seat—made up of seven fore-and-aft boards laid out in an attractive fantail pattern—are supported by a 1-1/2″ x 3/4″ athwartships bearer and a pair of cleats on the transom.

The boat’s outwale is made up of three pieces: first a rabbeted section of khaya that covered the end-grain of the top edge of the top plank, then a 1/8″ piece of yellow cedar for aesthetics, and finally another piece of generously rounded khaya, giving a total gunwale thickness of 1″.

Nigel Sharp

Nigel SharpThe volume created by the broad transom helps support a passenger seated in the stern.

Fitted along the bottom edge of the sheer plank, as much for style as for a guard, was another piece of 1/2″ x 3/8″ khaya tapered at the ends.

After khaya spacers to support the inwales for the open gunwale were then fitted, the interior received the same base coats as had already been applied to the exterior, and then three coats of polyurethane paint. The khaya got five coats of varnish. The inwales were installed, and the hull was then turned over for paint and brass keel bands on the centerline, alongside the daggerboard case, and on the bilge runners.

Various ancillary parts were made up: the 1/2″-thick khaya sole boards which bear on the floors, the rudder and daggerboard in 7/8″ khaya, and spars and oars of Sitka spruce. “The instructions and plans were nicely detailed and if ever there was any small confusion, we were able to figure it out,” said Sam. “We didn’t need to refer to Oughtred’s Clinker Plywood Boatbuilding Manual.”

The boat was launched on a gray, at first windless, day in June. Sam and the two students who had most helped him with the build, Sam Ferguson and Amaya Hernández, climbed aboard and rowed out of the Lyme Regis harbor; the tanbark lug sail that Sam had made hung limply. After a while I replaced Sam Ferguson and a gentle breeze soon came off the land. We then enjoyed a brief sail as the boat slipped along nicely in the flat water.

It didn’t seem too crowded with three of us on board until we tacked. That would have been much easier with two, but maybe with a little practice three people could negotiate a better procedure. Starboard tack was the favored one for the balanced lug rig, but any loss in performance on port tack when the sail was pressed against the mast was imperceptible.

Nigel Sharp

Nigel SharpThe Auk’s full bilges make a burdensome hull with good capacity. The stretched version here has room and freeboard enough for three; the 7’10” unstretched version will carry two comfortably.

At one point, a speedboat came close by at about 20 knots, and Sam and I watched the approaching wash with some trepidation. When it arrived, however, we were boat pleasantly surprised with how easily the Auk coped with it, giving us no cause for alarm. The boat was much more stable than we expected.

We needed to get back into the harbor before the tide went out, so we dropped the sail and I rowed us back in. The three of us we were able to keep the boat on an even keel with Sam one side of the tiller in the stern and Amaya on the opposite side in the bow. At first, I was worried that there might not be room for my fairly long legs, but I soon found I could use the stern seat as a stretcher. Although the 8′ oars felt too long for me, and the leathers were too thick and prevented feathering, I could tell that the Auk will be a nice, easy boat to row. Sam’s Auk will be used mainly as a tender for his parents’ 32′ sloop. He plans to fit a rope fender around the Auk, using some old heavy-duty hemp, while her sailing rig will stow in a bag strapped to the front of the mothership’s mast. She will certainly be suitable for her role as a tender, and the option of also using her for exploring rivers, bays, and coves under oar or sail will be a welcome addition.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry, and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Auk Particulars

[table]

Length/7′10″ or stretched to 8′10″ (as built here, 9′2″)

Beam/4′

Depth/19″

Weight/60 lbs

[/table]

Plans for the Auk are available from Oughtred Boats. Listed prices are in Australian dollars: $134.66 AUD (approx. $90.58 USD) for plans, $1235 AUD ($830.75 USD) for kits.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!