Henry Rushton, of Canton, New York, was a preeminent boatbuilder in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Living and working between the St. Lawrence River and the Adirondack wilderness, and his skill in designing, building, and marketing small boats allowed him a long career. Rushton may be best remembered today for his lightweight cedar canoes. His Wee Lassie is still a popular hull design built in all manner of methods. Maybe less well known these days are his pulling boats. According to Atwood Manley in Rushton and His Times in American Canoeing, rowing craft accounted for the bulk of his trade.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorIn the original boat, the planks were clench-nailed to the frames through the laps. Here they are riveted. A single copper clench nail secures the laps between frames. These planks have glued scarfs; the drawings show plank sections joined by scarf joints set in varnish and held with clenched 1/2″ copper tacks.

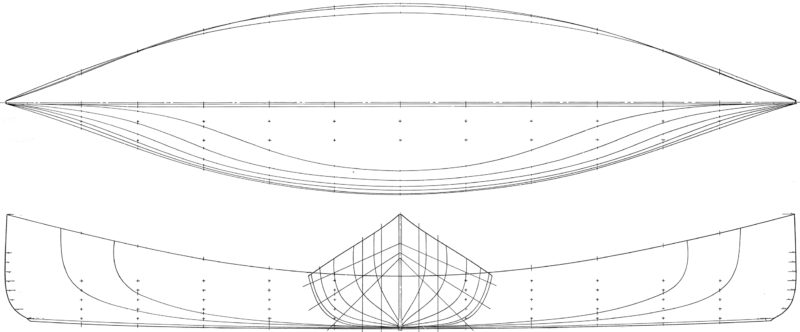

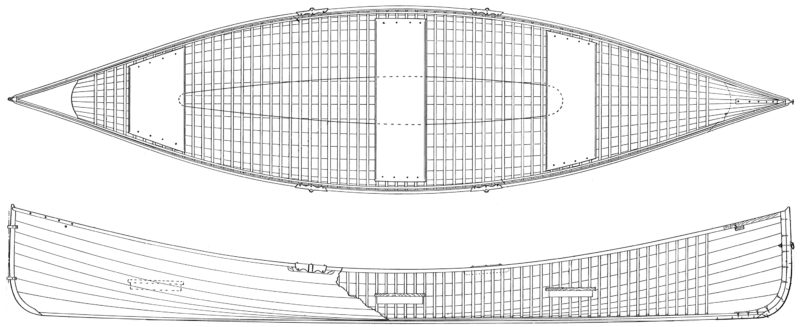

The Ruston 109 is an old-fashioned guideboat type combining lightness, good looks, and easy rowing. It’s a double-ender with nearly plumb stems, a lapstrake hull, and sweeping sheer. The boat is 14′3″ long with a beam of 39-1/4″. Many of Rushton’s pulling boats were offered as rowing/sailing combinations with a compact folding centerboard and a rudder with a yoke and steering lines. The plans for the 109 show no accommodation for sailing but do offer a rudder design. No doubt the fashion of the late 1800s allowed a fellow to pull hard on the oars, not seeing where he was going, while his amiable companion pulled the ropes.

My wife, Tina, and I have long enjoyed fishing the lakes, bays, and rivers of the mid-Atlantic states and northeastern U.S together. We’ve spent many fine days afloat in an aged, lumpy, chopped-off canoe that’s as slow as a slug. Last winter, with my shop idle, I decided to upgrade our fleet by building a spry fishing boat for two that we could also enjoy rowing solo. Anything much longer than 14′ would not fit in my work space. I’d never built anything with a transom, and I like the looks of double-ended craft. Happily, I came across Ben Fuller’s 87 Boat Designs: A Catalog of Small Boat Plans from Mystic Seaport’s Collection and found, on pages 56 and 57, a Rangeley Lakes Boat and the A.L. ROTCH, Rushton’s 109. I had an affinity for the Rushton; as a boy, I spent summer vacations with my family at a camp on a lake not far from where J. Henry plied his trade.

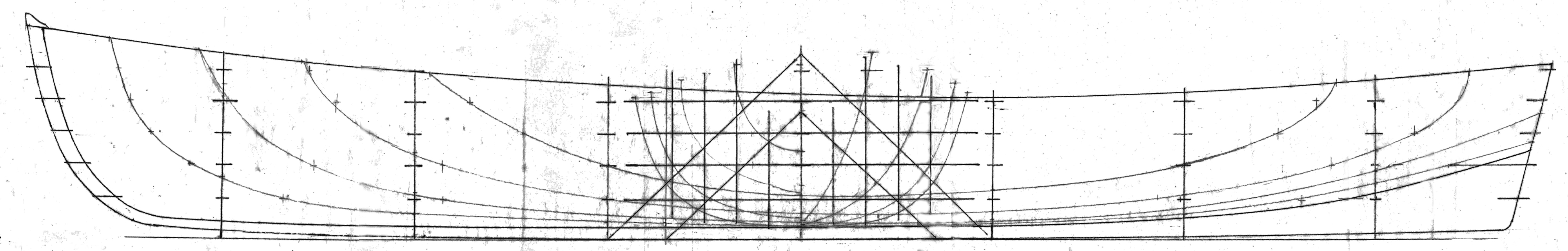

The plans for the Model 109 come from Mystic Seaport on three sheets: lines, offsets, and construction details. The hull is symmetrical fore and aft, so lofting half of the boat is all that’s required, though to ensure fair curves I did run my battens beyond the middle station. While lofting, I changed the vertical keel to a 4″ plank. The Rangeley Lake boat is built this way, and I had read that Rushton’s sailing canoes called for red-oak plank keels. I might one day want to add a folding centerboard and sail rig, but am now heeding the advice of Mr. Fuller that this would be “more successful in a longer and wider model.”

The plans call for all of three thwarts to be 5/8″ oak, like the center thwart here, but the cane seats, meant for a canoe, are lighter and more comfortable.

Station spacing on the plans is 14”. I set up five molds 28” apart, with two stem-end molds 68” from the center mold. I got out the 13′3-1/4″ keel from 4/4 ash and worked the rabbet. The plans indicate a steam-bent, two-piece stem, but I laminated them with ash strips and made two bending forms so I could glue them both up in one day. The stem-keel marriage was bedded with 3M 5200 and riveted. The backbone was then attached to the molds, and the stems plumbed and secured for building the hull upside down.

I began planking by spiling a pattern for the garboard, keeping an eye on the plans for plank width. Each plank has one scarf, as my northern white cedar stock ran mostly 8’ to 10’. After the garboards were bedded and screwed in, the rest of the planking continued. I fastened the 1/4″ planking with 5/8″ clench nails, being mindful of the spacing of the ribs, which would be installed later. I beveled the stems as I went, first clamping planks to the molds at their lining marks and filing for fit. Planks were bedded and screwed at the stems. There are eight strakes, and the sheer is especially shapely.

The center thwart can serve as a stretcher when the boat is rowed from the forward station.

With planking complete, I cut the plank ends flush with the inner stems and then bedded and attached the outer stems. After plugging the countersunk screws, I turned the hull upright for planking. The plans call for clench-nailed 1/2″ x 1/4″ half-round elm ribs spaced 2-1/4″ on center. In Appendix B of Atwood Manley’s book there is a detailed description of the method Rushton’s crew used in framing. One held a specially grooved backing iron while another quickly hammered home the clench nails in the short time the rib remained pliable from steaming. Because I generally work alone, I’m more comfortable riveting frames. I can bend, clamp, and screw steamed ribs to the keel while they remain supple and return after they’ve hardened for riveting through the planks. I spaced 9/16″ x 1/4″ rectangular white oak ribs 3-1/2″ apart and fastened with 14-gauge rivets. The flat face of the frame gives a solid landing for the burr, and the heavier scantling allows a wider spacing while retaining strength and minimizing weight.

The breasthook (“deck” in canoe nomenclature) and rails are of white oak. The rails I attached as a set, fastening one end of the outer rail with screws through the planking and into the breasthook, and then setting the inwale in place and clamping all together following the sheer sweep. I placed 10-gauge rivets through every other frame. The remaining frames were fastened through the inner rail with ring nails. The thwarts were placed according to plan: white oak for the center and cane seats for the bow and stern. As work progressed, I sealed and primed where appropriate.

The depth amidships is 11″ and the stems rising 13″ above that, giving the sheer a deep and dramatic curve.

The bronze oarlock sockets are patterned on Rushton’s original design and made by Bob Lavertue, proprietor of the Springfield Fan Centerboard Company. He does fine reproductions of many Rushton accessories and owns a Rushton-built Iowa. I enjoyed making the brass mooring-ring assembly shown on the plans and also cold-hammered and bent some 3/8″ bronze rod for center thwart stiffeners. After finishing the removable floorboards, I fashioned an adjustable foot brace as depicted in Rushton’s Rowboats and Canoes: The 1903 Catalog In Perspective, by William Crowley, and made 6’6″ spruce oars.

To get our boat to the water, I made some trailer modifications to cushion the lightweight hull. Tina and I can easily place the Rushton on and off the trailer and carry it where we want. Trailering the boat also makes it easy when I launch solo at a boat ramp. It’s a bit overweight to manhandle alone but can certainly be cartopped. For long road trips I would prefer the boat riding on top to having it on a trailer getting peppered with gravel kicked up by the truck.

Getting aboard the Rushton is a lot like getting into our old canoe, though with its flat bottom, the 109 is steadier. Still, we generally board while holding the gunwales and make sure to plant our feet on the narrow floorboards, keeping our weight centered. Pushing offshore, the wide keel takes the grind instead of the planks. There are two sets of oarlocks. The center station is for rowing solo. Rowing from the bow balances the boat nicely with a passenger in the stern.

With these two adults aboard, the Rushton 109 sits in perfect trim.

You sit low in this boat. There hull amidships is only 11-½” deep between the floorboards and top of the gunwales, and the center thwart sits just 5-3/4″ above the floorboards. With the dramatically curved sheer, the oarlocks are far enough aft from the middle to have some extra elevation to give plenty of room for the rowing stroke with your legs straight out. I am 6’ tall and comfortably row solo at a steady pace with my heels planted on the foot brace. Tracking is superb in this light, fine-entry double-ender. A few short strokes get you going, and then it’s easy to maintain a rate that’s faster than walking speed.

With two aboard, rowing from the bow, I’ve found that the center thwart is ideally placed for bracing my feet. The 109 responds to the added weight favorably, carrying beyond a boat length with each stroke. And it’s a nimble craft. I can turn the boat 360 degrees from a standstill with nine pulling and backing strokes. The aft seat is 7-½” above the floorboards, and Tina reports that it is quite comfortable for an afternoon cruise, though the tight quarters in the stern make an all-day fishing trip feel a little bit cramped.

One day, I took two young neighbors out for a row in the Rushton. There was plenty of room for the three of us on board while we poked about looking at lily pads and little fish. I imagined myself at a camp in the North Woods, sitting in the stern seat, with my dad rowing and brother in the bow with a coffee can of worms between us and our fishing poles restlessly waiting for a strike. The Rushton 109 is that kind of a boat.![]()

Tom Devries and his wife Tina live in New Braintree, Massachusetts. Now that both of their kids are off to college, Tom DeVries spends more time in Beyond Yukon Boat and Oar, his woodworking shop, and imagines that away he and Tina will be spending more time together fishing, paddling, and sailing in little boats. In years gone by, Tom has pirogued on the Congo, canoed on the Yukon, fished commercially in Alaska, and sailed his skipjack on the Chesapeake.

Ruston 109 Particulars

[table]

Length/14′3″

Beam/3′3″

Weight as built by author/95 lbs

[/table]

© Mystic Seaport Museum, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library

© Mystic Seaport Museum, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library.

© Mystic Seaport Museum, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library

© Mystic Seaport Museum, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library.

Plans for the Ruston’s Pulling Boat Model 109 come as a set of three pages and include lines, offsets, sail plan, and construction details. They are available from Mystic Seaport for $75.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!