Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe Zhike Gravity Hook, left, and the Lixada 4-Claw Hook work in different ways and both performed well.

The grappling hook (also known as a grappling iron or grapnel) that I made a while back from some stainless-steel rod and a few cable ties worked well enough, but it was an awkward and dangerous thing to keep in a small boat. It rested with one claw always pointing straight up, like a caltrop, an ancient and wicked device of war that wounded anyone unlucky enough to step on it. Modern grappling hooks aren’t so hazardous. I found two different types, both welcome to stay aboard waiting for the opportunity to retrieve something underwater.

Lixada 4-Claw Hook

Opened up, the Lixada’s claws span 8-1/2″.

The Lixada 4-Claw Hook is 9″ long, has a span of 8-1/2″ between the tips of opposing claws, and weighs 26.3 oz. The central shaft is stainless steel and the claws, my magnet tells me, are some sort of steel alloy. The claws spin around the shaft on an internal threaded rod that pushes the round cap at the bottom out so the claws can pivot outward or fold against the shaft. Spinning the claws in the opposite direction locks them either in or out. The folding design makes the 4-Claw Hook quite compact and prevents the claws from digging into woodwork or the bottoms of my feet when stowed. The device is rated to 860 lbs, more than I could imagine ever subjecting it to, and the serrated claws keep whatever has been hooked from slipping away. It’s an elegant design with an aggressive grip.

The large round disk at left moves in and out on a threaded rod. Here it keeps the claw tips safely up next to the shaft.

The Lixada was quick to snag this 60-lb ride-share bike and held on to it during the lift to the dock.

Zhike Gravity Hook

On contact with something, the Gravity Hook’s jaws open up. The single plate on the jaw at left will slip about 1/4″ into the space between the double plates on the right, preventing slender items from slipping out.

The Zhike Gravity Hook is 5-3/8″ long, 3-1/2″ wide, and weighs 8.9 oz. The device is made of stainless steel except for the nuts and bolts—the magnet says they’re steel. The four pivot points allow the jaws at the bottom to open upon contact with something, then close when the Gravity Hook is pulled upward. For use as a grappling hook, a separate cross piece is set between the articulated jaws and two O-rings are rolled into a pair of notches to keep the device from opening and dropping the cross piece. The hook is rated to 772 lbs, more than enough for retrieving anything from a small boat.

When the cross-plate is installed, two O-rings roll down into a pair of notches and keep it securely held in place.

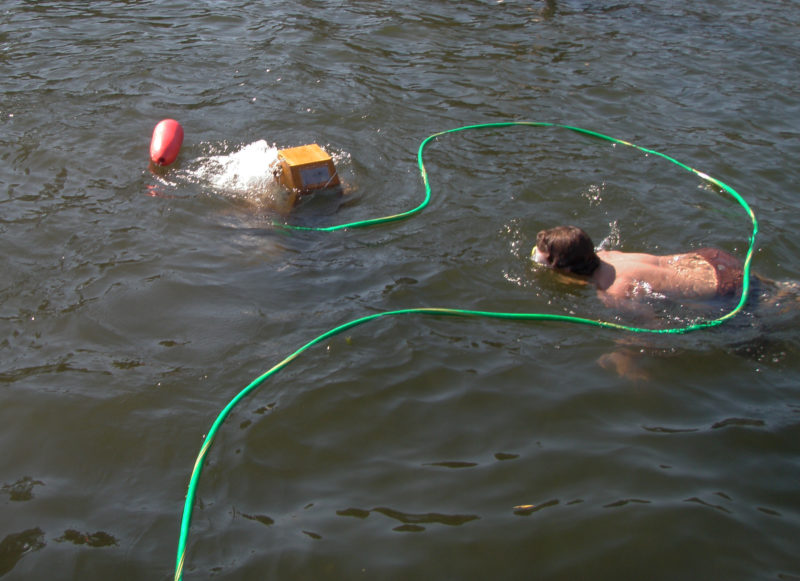

In its grappling hook configuration, you can cast about and drag for lost items, and it will snag line and chain, the wire basket and tubing of a shopping cart, but not anything with a diameter over 1-1/2″. For retrieving small objects like glasses and key rings, the Gravity Hook’s ability to grasp things make it better suited than an ordinary grappling hook. Using the opening jaws is best done when you can see what you’re fishing for. If you don’t have clear, undisturbed water, a face mask or a bathyscope will be helpful. The jaws have to be set directly upon whatever you’re after, so you need to be directly above it; and they have to be crossing the object, not parallel to it, so you have to be able to see what you’re doing. That said, we were able to grab a lost bright orange cinch cord on the first try.

The Gravity Hook got a hold on this sunken cinch cord on the first try. The milfoil came up on one of the hooks.

With both devices, it’s possible to get hooked on some immoveable object and join the ranks of items stuck on the bottom. Neither has an attachment point for a retrieval line, the kind used to retrieve a snagged anchor, but you could tie one on if you decide to go fishing blindly, or dive for it if the conditions and your ability allow.

The promotional copy for both devices suggests you can use them for climbing, just as Batman did with his grappling hook in the 1960s TV series. But if you’re going to throw the hook up to the top of a building or over a tree branch, you may not be able to get the grappling hook back if you can’t climb up to it. The Lixada and Zhike devices both supported my 220 lbs, but climbing is risky business, especially if what’s holding you up can get dislodged.

Both of these devices have the ability to save the day if something valuable is lost overboard in shallow water; they also can provide great entertainment fishing for the treasures that accumulate around the docks at marinas and launch ramps.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is editor of Small Boats Magazine.

The Lixada 4-Claw Hook cost $33.99; the Zhike Gravity Hook, $14.29. Both were purchased via Amazon.

Is there a product that might be useful for boatbuilding, cruising, or shore-side camping that you’d like us to review? Please email your suggestions.