In September 2013 I was perusing the Internet and stumbled onto a forum about an adventure race called the Everglades Challenge (EC). Intrigued, I found the homepage of an organization called the Watertribe where it described a grueling race that would test even the hardiest adventurers.

It begins at Florida’s Fort Desoto State Park in Tampa Bay and runs roughly 300 miles south to the Sunset Cove Hotel in Key Largo. How boats get there is up to their crews as long as they sign in at each of the three checkpoints along the way within the allotted deadlines. The boats are all small because each solo racer or team of two must drag their boats from the high-water mark to the water’s edge without assistance. The EC is unsupported; you’re on your own.

Thomas Head collection

Thomas Head collectionAfter the quick build we christened the dory JESS and set her in the water for the fist time.

The EC was in March, only six months away, and if I were to do it, I needed a boat. A man named Neil Calore had won the event in 2012 in some very tough conditions in a kit boat, the 17′ Northeaster Dory. I ordered the kit with a balance-lug rig, and it arrived in mid-December. It would be a challenge itself to finish by the end of January and have enough time for sea trials, but by mid-January I had a hull and spent the rest of the month making the seats, centerboard, and spars.

On February 3, 2014, we christened the dory JESS, after my oldest daughter. Sea trials followed. The dory rowed quite easily, and the lugsail proved to be a good choice, as it was simple and easy to handle, and moved the boat nicely—especially on a reach.

Thomas Head collection

Thomas Head collectionThe starting line of the EC is an impressive array of small boats stretched out across the beach.

Thomas Head collection

Thomas Head collectionI arrived at Fort Desoto one day prior to the race for last-minute preparations and race briefings. Just making it to the starting line is half the battle. The half yoke on the rudder and the push-pull tiller provide full control of the rudder without having to shift my position in the boat.

They say the hardest part of the EC is making it to the starting line, but on March 1 I stood there proudly with my boat and family, ready to embark. Shortly after the bagpipes played, the whistle was blown. The kayakers flew off the beach first, followed by the catamarans, then the larger sailing vessels. With most of the crowd away, I eased JESS into the water and was off.

Do I take the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) or the Gulf of Mexico for a more direct route? Winds were forecast at 5 to 10 knots from the northwest that first day. Ideal sailing winds and a calm Gulf made the decision easy. I rounded Passage Key and entered the Gulf. The winds were mild and I tried a little “motorsailing”—which is to say, rowing with sails up. I averaged over 3.5 knots. After I rowed for an hour, the wind picked up and I was making 4.5 knots under sail on a course to Stump Pass.

Thomas Head collection

Thomas Head collectionThe adventure begins under clear skies. A steady NW wind was perfect weather for sailing. Minutes after the start, JESS trails the sailing fleet.

The sea breeze kicked in that afternoon and I was surfing with a nice 2′ chop. The winds quickly picked up to a steady 15 knots and the Gulf built into steep, closely spaced seas. I was suddenly surfing white-capped 2′ waves doing almost 8 knots. I should have reefed, and I wanted to, but I had to keep the dory on a straight course and if I left tiller, I’d broach. I held on and ran with full sail.

But I needed to get out of these conditions. Running Stump Pass at night in big breakers was not an option. The GPS showed Venice Inlet 5 nautical miles away. It has long breakwaters that extend out 120 yards; I would have to jibe to sail down between them. As I crested a wave I made the jibe and was in the trough when the sail whipped over. A wave broke on the stern and the rudder came off. Luckily, I had tethered the rudder to the boat. The boat broached violently, and I sprang forward to drop the sail. It came down quickly, landing half in the water. With my sail and rudder both dragging in the water, I grabbed the oars and rowed hard to avoid the rapidly approaching rocks. My port oar was hitting the lugsail yard, limiting my stroke. I managed to get the boat to the middle of the channel, but the tide was ripping out against incoming rollers and I was stuck there and making no progress. I eased into the lee of the barrier rocks on the side of the channel, pulled the sail aboard, and rehung the rudder.

As I continued south along the Intracoastal, I berated myself for not following the rule of reefing early.

A little after 1 a.m., I made Checkpoint 1 at Cape Haze Marina, just south of Stump Pass. After getting into dry clothes, it was time to set up camp. I preferred sleeping in my hammock, but there were no trees available to string it to, so I arranged the boat for the sleeping bag. It was a short, restless night, but I woke around 6 a.m. in high spirits. Craving strong coffee and hot oatmeal, I set up my stove and made breakfast. After eating I felt strong and eager to get going.

It was 85 miles to Chokoloskee, the second checkpoint, and there are many different routes to it. I chose to take the ICW to Gasparilla Pass, and then move outside. This would allow me to avoid some bridges, channels, and boat traffic. I rejoined the ICW at Boca Grande, made good time, and arrived in San Carlos Bay early in the evening. I camped on Picnic Island rather than attempt Sanibel Pass at night and avoid running Big Carlos Pass, the next practical camp area, in the wee hours. I had covered only 35 miles, but I’d make up for this by getting an early start on day three. The hammock worked great, and I was asleep by 11.

I was up by sunrise and made it through Sanibel Pass to the Gulf. Winds were light but favorable; however by afternoon they picked up and I was reaching at a steady 4 knots. I arrived outside Big Marco Pass just after dark and ran Big Marco River rather than round Cape Romano. I coasted through the river and entered the Everglades in the wee hours Monday morning.

It was a dark, moonless night and there wasn’t an ounce of wind as I rowed through the small outer islands and back into the Gulf. Seeing the reflected night sky was like peering into another universe. Bioluminescence stirred around my oar tips and mixed with the starlight.

I rowed a few more miles and decided it was time to camp. No longer among the long barrier islands with sandy beaches, I was surrounded by clusters of mangrove islets. I approached several, shining my spotlight as I looked for a sandy spot to land. Roosting birds squawked loudly and hundreds of mullet jumped in the shallows. I eventually found a campsite.

I had been moving nonstop for 22 hours, covered 55 nautical miles, and rowed the last 12. I needed sleep.

The low-hanging sea grape trees and mangroves were not ideal for the hammock—their skinny limbs bowed under the strain. The hammock had mosquito netting, but in the time it took to climb in and rezip, 50 mosquitoes had made it in with me. I was too tired to care and quickly fell asleep to their steady whine. JESS, tied to a mangrove stump, rested on a patch of sand.

I woke around 7 a.m. and peered out at my little dory, high and dry about 30 yards from the water’s edge. It was dead low tide. The sand was littered with rocks and shells. I cleared out a path the best I could and tried to move the boat, but it was firmly suctioned to wet sand and wouldn’t budge. I finally managed to wrench it free and get it afloat.

Thomas Head collection

Thomas Head collectionI arrived at Checkpoint three, Chokoloskee, in the early afternoon. It was too early to stop for the day, so after a quick resupply of water I set out again for New Turn Key.

I hoisted sails and reached to Indian Key, the entrance to Chokoloskee, and arrived at Checkpoint 3 early in the afternoon. I cleaned up with a hose at a fish-cleaning station and refilled my water jugs. Refreshed, I headed out through a maze of mangroves toward the outer islands. It was a hard row against the tide, and I didn’t reach the outside until sunset.

I had a challenging night of sailing on a reach with 2’ seas. The wind eventually died, and I rowed the last 3 miles in a choppy Gulf and made it to New Turn Key around midnight. As I rounded the tip of the island, I aimed the spotlight on a wide beach that had a very shallow slope, but it was covered with large rocks and shells. The tide was dead low and there was about 30 yards of exposed rocky beach. I would normally set up a clothesline loop on the anchor to pull the boat out to deep water, but I was exhausted. I found shrubs to hang the hammock on and tried to get some rest. I didn’t manage much sleep; I could hear the dory getting beat up on the rocks as the tide eased in. I woke several times and pulled her as far out of the water as I could. The mosquitoes filled the hammock each time I opened it.

At sunrise I gave up trying to sleep and pressed on. The weather channel was chattering about a frontal system a couple days out and approaching South Florida. I could continue inside along the Wilderness Waterway to Flamingo, Checkpoint 3, or remain outside around Point Sable and enter from Florida Bay. My plan was to take the outside, weather permitting.

The winds were forecast as south at 5 to 10 knots, so I opted for Point Sable. The wind was light and I “motorsailed” with the oars. By afternoon the winds was a steady 15 knots. The waves were a steep 2’ and closely spaced–so much for the 5–10-knot forecast.

On a beat the dory, light and lug-rigged, couldn’t make progress south toward Point Sable. She didn’t carry the momentum needed to punch through the waves. I was 5 miles out and 38 miles north of Point Sable. Darkness would descend in six hours, and I was in a rough sea forecast for 6’ to 8’ the next day. I was very concerned. I needed a new plan.

Unable to sail, I decided to try rowing toward Point Sable. I rowed hard into the chop, but at my average of 1.5 knots, it would take 20 hours to row to Point Sable. Needless to say, I was daunted by the thought of spending the night getting tossed around on the Gulf. It was time to scrap Point Sable. Ponce De Leon Bay was 6.85 miles away, and from there I could pick up the last of the Wilderness Waterway.

I plugged the coordinates for the bay into the GPS and started rowing hard—really hard, still averaging a knot and a half. If I maintained this pace, I’d make the entrance by sunset. Failure was not an option. I took it one mile at a time.

I neared the bay entrance just before sunset. The closer I got to the shoreline, the shallower the water became. The wind started ripping and the waves turned into breakers. The dory made a cracking sound as it slammed into the backs of the largest waves. The last mile was the worst. Once again, I was spent and had to dig deep.

Rounding the last point at the northern edge of the bay and entering Shark River, I was thrown a real treat: a favorable tidal current. For an hour I rowed the twisted river, making 5 knots over the bottom. I tore into a can of smoked oysters and chased them with sardines, then entered Whitewater Bay just as the sun set.

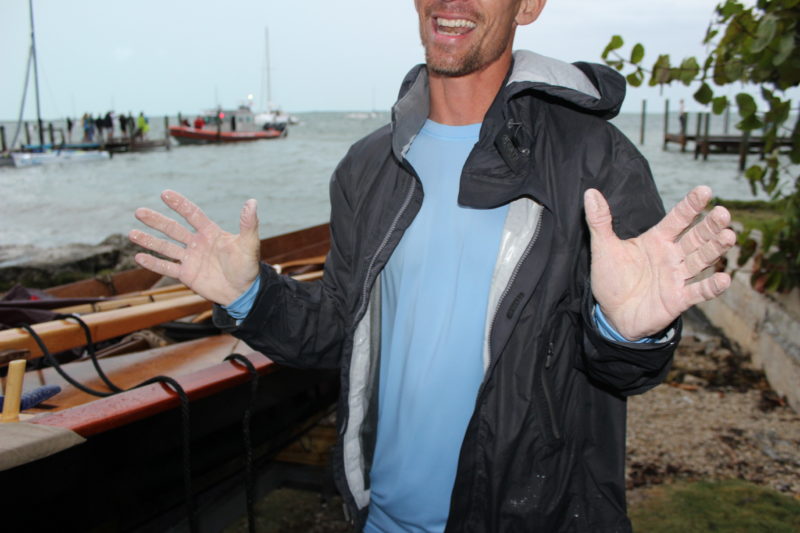

Thomas Head collection

Thomas Head collectionAfter spending most of the day in rough, windy conditions my hands were quite waterlogged.

I rowed what seemed like an eternity through the canal that leads to Flamingo. I arrived at Checkpoint 3 shortly after 2 a.m., having covered 50 miles, 15 of them rowed. I had a bad blister on my lower back from leaning into the centerboard trunk on the pull stroke. My sleep-deprived brain seemed to be operating in slow motion, and simple tasks were a challenge.

Fantasizing that Flamingo was a luxurious resort, I imagined indulging in a hot bath, a four-course meal, and a good night’s sleep. What I got was a horde of mosquitoes, a cold sink in a muddy bathroom, and dehydrated beef stroganoff. Several kayakers were already snug in their tents when I arrived, and by the time I set up the hammock it was after 3 a.m. I was giddy at the thought of a good night’s rest.

The skies appeared clear, so I didn’t set up the rain fly. The usual mob of mosquitoes joined me inside the hammock. I fell asleep quickly but was awakened about 30 minutes later to the rumble of thunder and gusty winds. I rolled out of the hammock as the rain began to fall, and retrieved the rain fly from the boat about 100 yards away. I set it up as quickly as I could in the rain, with the mosquitoes attacking me.

Thomas Head collection

Thomas Head collectionIn the predawn light I made a last check of my gear. We’d been warned not leave any food stored in boats overnight. Raccoons would have raided the stores. I was glad I covered the boat with a tarp because it also kept everything from getting soaked from a heavy dew.

So much for a good rest. Around 5:30 I woke and peeked outside. All the kayakers were gone. Feeling like I’d overslept and was late to work, I jumped into action. The wind was forecast to blow 20–25 all day, and I was glad I wasn’t on the Gulf. A little reorganizing of the dory, and I was rowing Flamingo Channel out to Florida Bay.

I had studied the charts of the bay for many hours in preparation for the Everglades Challenge and had a good plan to get across. The winds were very strong, out of the SSW at 20 knots. I rowed up to the last channel marker, put in a double reef, and raised the sail. Off I went with a ripping wind.

The channels were well marked, and I flew along on a broad reach averaging 5.5 knots. I could be at the finish line by early afternoon. I exited Twisted Mile and popped out into a very steep, nasty chop. Sheeting in the main, I tried to point to Jimmie Channel. Waves washed over the rail filling the dory, and I sailed with one hand and bailed with the other. There were rocks to leeward and I couldn’t ease off. I steered a few degrees downwind of the channel entrance—the best I could do—and ran aground in muck just shy of the entrance. Hopping out, I sank to my thighs, leaned on the boat, and trudged to deeper water. Afloat again and with the oars ready, I jumped back in. I was soon back on a reach making good time.

A quick jog through Manatee Pass, and I was back in a protected bay heading toward the Intracoastal Waterway and very close to the end of the race. I sailed by a fellow competitor in a kayak and we exchanged greetings. As I approached the Intracoastal, I paused to put Sunset Cove in the GPS. The kayaker passed me, paddling very casually. With the numbers entered, off I went. Glancing astern, I couldn’t believe what I saw.

Dana Clark

Dana ClarkThis storm hit when I was about two miles from the finish line and packed high winds. Weather can be big challenge and the EC officials emphasize that you are the captain of your ship and should not venture out in conditions that you’re not confident that you can manage safely.

The sky was black from one end to the other and a roll of clouds was closing fast. There weren’t any islands close enough to provide a lee. I was smack in the middle of a bay. I’d just have to deal with the storm when it hit. I passed the kayaker and pointed astern. He looked, whipped around and took off at an Olympic pace.

I was a half a mile from shore—I could see the houses and docks clearly—when the front hit with a sudden gust. I dropped the sail. A wall of rain sped toward me and when it hit I lost sight of land. It was blowing from the west, gusting over 40. The dory didn’t seem to care and ran with the wind under a bare pole. I simply sat and waited. I knew I was rapidly approaching shore, but couldn’t see it. If I washed up on rocks, JESS would take a horrible beating. I hoped for a rare sandy beach. Suddenly I saw a green marker and started to make out the shoreline. I steered to starboard and a red marker appeared. I was going to make it.

I coasted into the marina of Buttonwood Bay Condos. People on their balconies watched the storm, and I waved to them as I coasted into a nicely protected slip. They looked a little puzzled.

Dana Clark

Dana ClarkHaving sailed through high winds and driving rain, I approached the finish with a deep reef in the sail.

The storm let up after about 30 minutes, and with a light rain and strong but steady wind again I raised a reefed sail and headed out. The looks from the condo dwellers went from puzzled to stunned as I left marina. I was 5 miles from the finish.

Dana Clark

Dana ClarkI arrived at the finish smiling at the sight of my three girls waiting for me. It was the first time I’d seen them since the race started. One of the great gifts of the EC is a fresh perspective on what truly matters.

Rounding the point into Sunset Cove, I looked for a crowded dock. I snaked through anchored boats and then saw people jumping up and down waving and cheering. It was the finish line. The whole scene was a little overwhelming. My brain was foggy and processing very slowly, and I stopped the boat just short of the dock to allow my mind to catch up. Then I spotted my family in the crowd.

Dana Clark

Dana ClarkFinishing the EC requires a steady if not grueling pace. The final days of the EC are the toughest, your brain is foggy and your body is worn from working the last few days in a saltwater environment.

It was over. The Everglades Challenge had lived up to its reputation. Both my body and mind had been tested, and both were, at last, relieved.![]()

Thomas Head collection

Thomas Head collectionAfter the race I posed with the T shirt bearing my Watertribe name. In my left hand is the award for the win in my class and in my right the coveted shark’s tooth awarded to all finishers.

A native Floridian, Thomas Head grew up working on his father’s home-built stone crab boat in the small coastal town of Inglis. He has 19 years of service in the U.S. Navy. Thomas ranks his boatbuilding and sailing skills as novice at best, but he loves wooden boats. His review of a handheld depth finder also appears in this issue.

The Everglades Challenge

The Watertribe‘s Everglades Challenge is a tough seven-day adventure race with a few rules that make it unique and challenging. The primary rule is that racers are on their own from start to finish and entirely responsible for their own wellbeing. Self sufficiency is very important because the course goes through some very remote areas; you may go a couple of days and not even see another racer or have cell-phone coverage. Racers should not expect any assistance unless they activate an ELB in an emergency.

Boats may only be human or wind powered and must be dragged by the racers without any assistance, if only at the start at the start—about a dozen yards from the high tide mark to water’s edge. This requirement keeps the boats small. There are four classes of boats: kayaks, sailing catamarans, monohull sailboats, and experimental craft. The starting line of the EC is an awesome sight of cool boats outfitted to the gills for a serious expedition.

Each racer must sign in at all three checkpoints by a set deadline. The time allotted between points requires racers to keep moving. It is about 60 nautical miles from the start to the first checkpoint and racers are given 29 hours to complete that first leg. That’s an average of two knots without stopping. Factor in stops for sleep, weather or other contingencies and the result is a pretty aggressive timeline. Subsequent checkpoints are farther apart and are given more time, but a steady pace is still required. Most racers will complete the 300-nautical miles in four to five days.

Just making it to the start of the EC is no easy task and requires a lot of preparation and commitment. When the whistle blows, racers drag, push, and even roll their boats to the water’s edge. They will tackle a wide range of coastal conditions, headwinds, storms, ripping tidal currents, exposure and fatigue. Racers must have a measure of mental toughness just to keep moving forward. Those who attempt the EC are guaranteed a fresh perspective on what is hard and meaningful in life and for those who finish, a great sense of accomplishment and confidence. —TH

Really enjoyed the story including the info about the boat. Have been thinking about building a small open sailboat and have considered several designs. I will definitely check out this kit as I think I’m more apt to get her built in a timely manner.

I have been following the EC for several years now and greatly injoy the first person accounts.

I really enjoyed the article on the Everglade Challenge. This is my favorite part of the magazine. I also enjoy new products and review. Great Job, keep it up!!

At 77, I’m too old and infirm for this contest, but I can definitely relate. In 1951 at age 14, my father bought me an open, Lightning-class sailboat at Coconut Grove Yacht Club and in mid-January, he, my late brother and I sailed the boat from Biscayne Bay to Sarasota Bay on the West Coast. No one kept a log and no one took a photo, but I’ll never forget myriad memories of that voyage and the planning it took to be totally self-sufficient for several weeks.

Bravo Deke! I have followed the Everglades Challenge in “real-time “for a couple of years now as I belong to a Yahoo group for the Triak, a multi-hull sailing kayak. We have had a couple of EC participants over the years. Finishing this race is certainly a huge accomplishment. Finishing construction of your boat at record pace is also noteworthy.