photographs by the author

photographs by the authorShinto’s Planer Saw Rasp (top) and 9″ Saw Rasp

Over the years I’ve gathered up a lot of rasps, usually with high hopes that their shark-like rows of teeth would cut through wood with ease, but none did much more than gnaw. I’d never grown fond of any rasp until I bought a Shinto Planer Saw Rasp. It’s just as effective rounding the tip of a dory’s oak stem as it is fine-tuning spruce tenons for a Greenland kayak. While I’ve always just accepted that the Shinto works well, I’d never taken a really close look to see why. At first glance it looks nothing like an ordinary rasp. Instead of being a bar of gray steel with rows of teeth, the Shinto is a lattice of what appear to be wavy hacksaw blades.

The lattice design helps to prevent clogging, not so much because the open structure provides space for the wood debris—most of that gets pushed away with every stroke—but because the teeth aren’t in rows. It’s easy to push one person off a chair; difficult to shove a row of congregants off a pew. The vast majority of the teeth on the Shinto are loners, like the single person on a chair. There are some shoulder-to-shoulder pairs where the blades touch and that’s where little bits of material get stuck. Compare that to an ordinary rasp where the clogs accumulate in the rows.

The machine-cut teeth of this rasp curve up on the back side to the cutting edge, creating a point of contact that is nearly parallel to the work and making it difficult for the rasp to engage the wood.

The teeth of an ordinary rasp are gouged up from the metal’s surface, each having a little triangular hollow in front of its cutting face. You can see that the tool that made the groove had a sharp point, but the teeth it creates are not themselves pointed, even on expensive hand-made rasps. Instead they’re shaped a bit like Half Dome in Yosemite—a rounded mound with a flat vertical face. The teeth of some machine-made rasps have another thing in common with Half Dome: The edge of its sheer face isn’t quite at the summit, and engaging similarly shaped rasp teeth in wood requires a lot of pressure.

The rounded high point of this machine-cut rasp tooth, not its cutting edge, is what makes contact with the work.

The teeth on my round rasp are poorly tempered and have bent away from the work.

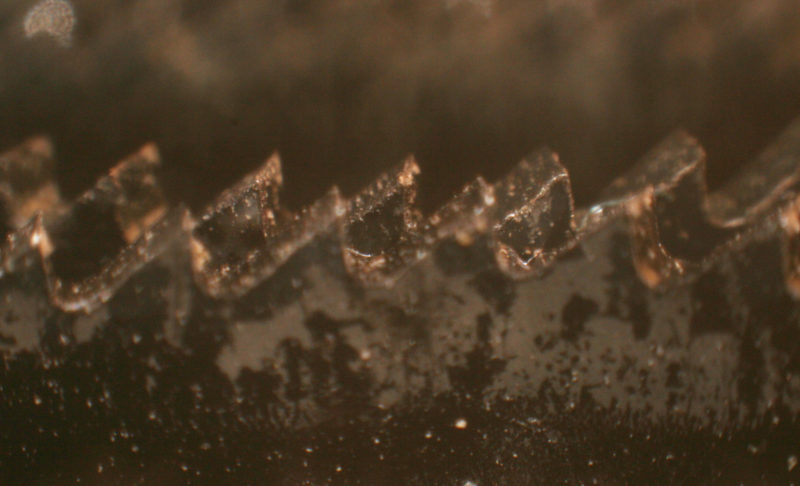

The Shinto’s teeth are cut, evidently, as they are in hacksaw blades, with a mill grinder—a rotary cutter that moves across blade blanks and cuts all of the teeth in one pass. The front face of each tooth is vertical and the cutting edge across the top is straight, just like the teeth of a ripsaw. The backside of each tooth slopes directly away so there’s nothing to keep the cutting edge from biting in. The teeth are well tempered and make quick work of brass, aluminum and even steel—as you’d expect of hacksaw blades—but I prefer to extend the life of my Shinto tools by using them only on wood.

The teeth of the Shinto Saw Rasp have straight cutting edges, all parallel with each other for a smooth cut. These are the teeth on the coarse side.

These are the teeth on the fine side of the Shinto Saw Rasp. The teeth in the center of the image are at the contact point between two blades. Staggered, they don’t get clogged.

The sides of the Shinto rasps aren’t straight; they curve in a bit at the rivets that hold the blades together. (The blades aren’t welded where they contact each other.) The concavity at the rivets “buries” their heads so the rasp can be worked into the corner of a right angle.

I have several common rasps with smooth sides that can also be worked in a corner, but the teeth on the working faces of those rasps don’t extend fully to the edge and leave a ridge of material that has to be removed with some other tool. The Shinto has a full complement of teeth right up the edge. Those outside teeth are ground back at a bevel, a special operation done only on the two outside blades, so there must have been a reason to add the extra step in the manufacturing. In a right-angle tenon the bevel would leave a fillet of wood just 3/100” wide, which is hardly worth fussing over, but in an obtuse angle, like the beveled shoulders of the tenons I cut for Greenland kayaks, the Shinto won’t cut an unwanted groove in the apex.

Shinto rasps come in two styles. The Saw Rasp has a handle in line with the cutting surfaces and the Planer Saw Rasp has an offset handle. The offset handle allows work in the middle of large flat surfaces and is removable, so you can switch between the coarse side and the fine. My Planer Saw Rasp came with a knob extending forward for my other hand, but I removed it, preferring to have my left hand on the back of the rasp itself for a better feel for the work.

The Shinto does faster and smoother cutting with less effort than with a common rasp. Because its teeth aren’t aligned in rows you don’t have to angle the tool to keep it from getting hung up. Pushing a common rasp’s rows of teeth straight across the edge of a board is like negotiating a flight of stairs with a hand truck. The Shinto rasps leave a noticeably smoother surface when worked with the grain and excel at working across end grain. Are you fine-tuning the end of an inwale for a perfect fit with a breasthook? The Shinto is the tool for the job. I’ve had my Shinto Planer Saw Rasp for at least a decade, maybe 15 years, and it still has plenty of bite and remains a pleasure to use. My other rasps? They’re under a blanket of dust waiting for me to brush their teeth.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

Shinto rasps are available from the WoodenBoat Store, woodworking stores and web sites.

Is there a product that might be useful for boatbuilding, cruising or shore-side camping that you’d like us to review? Please email your suggestions.

I purchased both of these fine rasps not long ago and they are everything this article states. An amazing and very worthwhile tool.

How does this compare with a cabinet maker’s rasp?

Cabinet maker’s rasps have one flat face and one curved face, with the same type of teeth covering both sides; there are several different grades of teeth—called grain—from coarse (grain 1) to fine (grain 15). The edges of these rasps are sharp and toothed, meant for cutting notches. The top-of-the-line rasps are handmade with each tooth “stitched” with a cutting tool called a barleycorn pick and a special hammer. Each tooth has to be made with the same impact of the hammer to be raised to a uniform height. The pattern of the teeth is slightly irregular so the rasp won’t leave grooves like a machine-made rasp will. Handmade rasps are pricey, from around $60 to more than twice that.

I took a look at some hand-stitched rasps at a woodworker’s tool store and under magnification the teeth showed the same “Half Dome” shape as the rasps I own, but had their cutting edges high, where they’d be more effective.

I use the saw rasp, a very effective tool, brutally sharp, with good control. I think it would be worth having the planer saw rasp as well: Handles attached to the end of the rasp often get in the way. Speaking of rasps, another good tool is the horseshoe rasp. It’s a big meaty thing—a conventional, large flat bar, course and fine sides with filed edges so you can work along a corner. No handle, not the ones I have used. They may suffer some of the same design deficiencies pointed out by Chris, but I find that a proper horseshoe rasp will last me at least a few years with a fair amount of use. They’re generally found at tack shops or grange supply houses.

I bought my Shinto rasp about 25 years ago while living in Japan. I needed a few tools to maintain the old building I was living in and couldn’t find a rasp that I was used to and so settled for the Japanese version of a rasp. It didn’t take me long to realize I had stumbled onto something great. It has always intrigued me how it can peel away the wood so fast yet leave a relatively smooth surface. And even after 25 years of frequent use it still cuts well enough that I’m not looking to replace it anytime soon.

I bought the Shinto planer rasp maybe 8 or 9 years ago to use for building my Penobscot 14. I don’t recall it being too expensive then, maybe $20 or $30. It immediately became the go-to tool for everything I needed to do rough or fine. It really is an amazing tool and I couldn’t imagine going back to other rasps. Removing the front handle never occurred to me. It mostly gets in the way, and I will definitely remove it and see what effect that has.

The cutters on a Shinto rasp always reminded me of tiny-toothed bandsaw blades riveted together. Very effective.