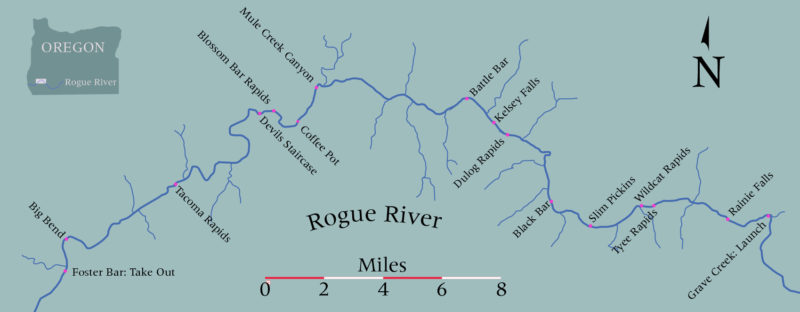

Several years ago I stood high on a scouting rock next to the Rogue River looking over the rapid that would, from that day forward, run through my daydreams and nightmares. The Rogue flowed gently around the corner after the constricted and chaotic Mule Creek Canyon and fanned out at this deceivingly beautiful point where autumn’s splashes of red and burnt orange were dabbed among dark green trees lining the steep banks. The water pooled above the rapid was peaceful and serene until it dropped over the entry point and tumbled hard and fast through a complicated maze of boulders the size of trucks, jagged rocks that rip open rubber rafts, and narrow chutes that break boats. It was Blossom Bar, a Class-IV rapid just beyond the halfway point on the 36-mile Wild and Scenic section of the Rogue in southwestern Oregon. It has been flipping rafts, smashing drift boats, sinking kayaks, and terrorizing boaters for decades. Blossom Bar was once so strewn with boulders that boats had to be portaged across it, but Glenn Wooldridge, an early river runner on the Rogue, dynamited a passage in the 1950s (see video: Blossom Bar Blasting). While Blossom can now be run, it has claimed several lives in recent years.

When I stood on that rock for the first time, I was surrounded by a crew of experienced river runners, watching as the group right before us struggled to hoist an 18′ rubber raft off the Picket Fence, a line of jagged rocks it had hit when it missed the first turn to the right. While they hauled on an elaborate rigging of ropes and pulleys, one crew member sat off to the side, alone, with his head in his hands, and his arm in a makeshift splint—a casualty of a river mishap that had occurred just prior to our arrival. My freshly varnished hand-built mahogany-plywood drift boat barely had a scratch on it, and I was as worried about what the rapid might do to it as much as what it might do to me. I’d been told so many times that rapid and the whole lower Rogue is no place for a boat made of wood that I’d started to believe it.

I made it through the rapid that first time without a scratch, but that was a thousand river miles and several thousand rapids ago. I’ve been on many of the rivers in Oregon, chasing fish, and running rapids in my wooden drift boat, and each river has a distinct personality. Some are fussy, some are sophisticated; others are fickle, elegant, classy, and even sacred. But the Rogue is a breed apart. It’s the river where Zane Grey did his best writing, where John Wayne and Katherine Hepburn, Merrill Streep and Kevin Bacon made movies; it’s a river where famous athletes and dignitaries have fished. And it’s a river that doesn’t suffer fools lightly. The Rogue is rowdy. Rough and rugged, it represents the American West when it was wild. The Rogue brings out the best in me as a river runner, a fisherman, and an outdoorsman. I’ve run the lower Rogue in every season of the year, in a wide variety of weather conditions, always with the same wood boat and mostly with the same river crew.

Greg Hatten

Greg HattenThe calm of Kelsey Canyon creates a nice opportunity to get lost in the steep mossy walls, the deep green of the towering trees, and the emerging colors of fall on the hills looming over the river.

Last fall was different. Almost everything I knew about the river changed in 2015 because of an historic low water level. River levels all over the West were at all-time lows because of the lack of rain and snow. None of us had ever seen the Rogue so low. All summer we had watched the levels continue to drop, and as our early October permit date approached, we debated whether we should run it at all.

A few days before our scheduled put-in, I spent a couple of days and cold nights high in the Cascade Mountain range exploring Crater Lake National Park, very close to where the Rogue River gets its start. I was amazed at how the deep dark blue of the lake could upstage such a beautiful cloudless October Oregon sky. Just a few miles from the rim of Crater Lake, on the north flank of Mount Mazama at Boundary Spring, life begins for the Rogue River. Unlike many Northwest rivers that start out as a quiet trickle from glacier melt, the Rogue bursts out of the ground with all the power and drama it’s known for downriver. It surges from the ground almost as if someone turned on a fire hydrant and left it gushing. The cold, clear water races down the western side of the divide, carving a path through a series of chutes and sharp drops as it runs under and over moss-covered trees that have fallen all around the narrow passages of the river.

There was no evidence at the river’s source that the drought in the West had any effect on the personality or the pulse of the rough and tumble Rogue. But as I drove down from the heights of the mountains and along the river, it was clear from the waterlines on the shore and the exposed rocks in the river that this year’s flow was well below average. Some of the tributaries that normally feed into the Rogue were practically dry and the snowmelt was long gone, leaving the river much rockier and rougher than usual.

While I was in Crater Lake Park and disconnected from cell phones and emails, word went out that a drift boat was jammed in the middle of the narrow slot canyon known as Mule Creek Canyon and the Wild and Scenic Rogue was closed by the Bureau of Land Management until the boat could be removed. Our trip was off. My heart sank when I read the notice and saw the pictures my friends had circulated of the boat wedged tight in the canyon channel unable to fit through the narrow passage. The bow was caught on one side of the canyon wall and the transom on the other, while the water kept the boat pinned on its edge. No one had been seriously injured, but the boat was a mess. Moments after I read the notice word came through that the current had broken the boat, folded it, and flushed it downriver. Our trip was back on.

We headed to the rustic riverside Galice Lodge with our rigs, boats, and supplies ready for a week of river running. I was coming from Crater Lake and was the first to arrive in the early afternoon. I headed to a great little riffle just downriver from the Lodge; three fish later, I trudged back up the steep bluff to connect with the river friends I hadn’t seen since this same time last year.

All of us, including Scott, our trip leader and one of the best oarsmen on the planet, were anxious about the low water level. Even Debbie, the owner of the lodge and “Goddess Divine of the Rogue,” advised against going. She has been on the river all her life and had never seen it so low. She stopped renting her river rafts several weeks prior because her gear was getting torn up by inexperienced boaters in low water and sharp rocks. We talked about it and decided to launch anyway.

We pulled out early the next morning for the short drive to the Graves Creek put-in at the upstream end of the 36-mile Wild and Scenic section. We shoved off from the boat launch into a pool of calm water, and in a mere 200 yards we reached the chaos at the top of the Class-III Graves Creek Rapid. The low water was immediately evident as the bottom of my boat bumped boulders in the middle of the rapid where I had never before touched a rock. Running the river at this level would be a huge challenge requiring vigilance and skill, particularly in the back-to-back Class IVs: Mule Creek Canyon and Blossom Bar. They were two days away, but already on my mind.

Just a couple miles from the put-in at Graves, there is a waterfall with a drop so vertical and violent you can hear the deep thunder of crashing water on rocks for a quarter mile upriver before you can see the cloud of mist that hangs above it. It’s Rainie Falls, classified as an “unrunnable” Class VI, the highest designation for degree of difficulty on North American rivers. On river right there is a narrow rocky lining chute that makes it possible to avoid the falls if you are willing to wrangle your boat through a more gradual elevation change in the form of something that resembles a ragged stone staircase for King Kong with water running down it.

Greg Hatten

Greg HattenTo get around the unrunnable Rainie Falls, we lined our boats in the skinny side channel known by many names, the only printable one being Fish Ladder. It required all hands and a couple of hours to get ten boats through the narrow rocky chute.

We pushed and pulled and squeezed and coaxed the rafts down that rocky narrow flight of stairs one by one and only lost control of one raft. It happened on the last narrow section at the bottom; the raft got stuck and with water starting to pour over the sides, we released the rope and let it go rather than let it sink. Two rowers quickly jumped in an empty boat, chased the runaway down river and pulled it to shore.

When it was time for my wood boat to run the gauntlet, I tied my 100′ rope to the transom, gave it a little nudge, paid out some line, and watched the river current take it 20 yards down to the lip of the first stair step where it got hung up by low water. It teetered for a few moments with the bow hanging precariously over the 5′ drop until the water built up behind it and sent it over the edge in a nosedive. I held my breath hoping there was enough water to break the fall. There was water, powerful water, and it grabbed my boat and shot it forward. I did my best to hold onto the rope but it screamed through my gloved hands and left me with painful rope burns. My boat bumped the bottom several times and slowed down before it reached the next stair step and I repeated the process four or five times until the last narrow pinch. The pinch was too narrow for the rafts and I knew it by looking at it that it would be too narrow for my boat.

The water surged as it forced its way through the slot and it grabbed my boat and almost pulled me off my feet. I let out line and as the boat did it’s best to fit through the opening, I heard the awful sound of wood scraping the canyon wall as the rocks on the right side carved a scratch down the entire length of my boat. Since I’d built the boat and would have to repair the damage, it was like hearing the scratching of fingernails along an eight foot chalkboard: excruciating. Lining a group of boats around Rainie Falls in normal flow usually takes us 30 to 45 minutes. Low water conditions turned it into a two-hour struggle.

Greg Hatten

Greg HattenThe view of the sunset up river from our camp below Tyee Rapid was stunning as the shadows crept up the mountains and dusk overtook the day.

We camped at the bottom of a Class-IV rapid called Tyee. It has a spacious area of gravel, sand, and brown grass, with plenty of room for the boats and a huge level area for our campsite. The weather was unseasonably warm, and we took advantage of it that night. Not one of the 10 of us set up a tent. We all preferred sleeping in the open air with the stars overhead. I threw down my cot and bedroll next to my boat and soon fell asleep

Scott Vollstedt

Scott VollstedtThe narrow opening on the right side of Slim Pickens left no margin for error as it was just a little wider than the boat. To run it in a wood boat at low water levels required plenty of nerve.

Our second day on the Wild and Scenic section was filled with tricky Class II rapids, starting first thing in the morning with Wildcat, and then Slim Pickens, Black Bar, Dulog, and Quiz Show. They were all sharper and more technically demanding than usual and we were constantly scanning the water for ragged rocks just below the surface. Everything was harder. The low water had turned the Class IIs into Class IIIs, and the Class IIIs into Class IVs.

Scott Vollstedt

Scott VollstedtBlack Bar Rapid is a Class III and normally, only the top of this rock in the middle is exposed. At low water, it becomes a big obstacle that must be missed.

After an exhausting day of rowing we pulled into Battle Bar Camp, the site of a bloody skirmish between the U.S. Army and the Rogue River tribes over 150 years ago. The campsite is one of our favorites with plenty of room for tents and cots. I hauled my gear 100′ up a narrow winding trail to a small flat area on the edge of the bluff with a commanding view of the valley downriver, the steep tree-covered hills of the opposite shore, and our row of colorful boats pulled up in a neat line at the river’s edge.

Greg Hatten

Greg HattenOne of the best sights on any river trip are the colorful boats pulled into camp each night after a hard day of rowing. Our campsite at Battle on the second night of the trip provided a bird’s-eye view of the boats and camp from the bluff above the river.

These boats mean the world to the men who row them. Each of us has found a craft that suits the way we row and the way we travel on the river, and while no boat or setup is the same, the connection we have with them is very much the same. We all have stories of close calls and near misses, and it’s always the boat that pulled us out, avoiding scrapes and averting disaster. Time after time, the boats deliver us from tight spots. We love our boats. Mine is a McKenzie-style drift boat. Nothing on the river is quite as pretty to my eye, and nothing I have ever rowed is quite as responsive. I built the boat and have shaped, sanded, and varnished every square inch of wood on it. I’ve rowed it for thousands of hours and hundreds of miles and know what it is capable of. I’ve repaired holes, replaced frames, resanded, revarnished, and refurbished most every part of it. My connection with it runs deep. When I am rowing the boat in sync with the river, everything feels effortless, time stands still, and I am part of the river. The boat moves nimbly with just a flick of my oars and the paths through the rapids come easy.

Scott Halpert

Scott HalpertOne of the best parts about running the Rogue in autumn is the vibrant color along the hills lining the river. In between rapids, stretches of calm water like this one just above the Battle Bar camp site provided good opportunities for fishing.

After a campfire dinner down by the river, we talked about our running order, the meeting time above the rapid, and the effect the low water level might have. I took my river book out of my boat to review my river notes from previous years. The first page I turned to had a note from a few years back when the water was low, and in big bold red permanent marker I had written, “NEVER run this river below 1,100 CFS.” When we launched at Graves the level had been 950 cubic feet per second.

In the morning I sat up on my cot, still wrapped in the warmth of the bedroll and blankets, and admired the vivid colors on the hill across the river. The yellows and reds of fall were even brighter with the morning dew. I was eager to take on the day’s challenges but anxious about the risk the rapids ahead posed to everyone on the team. When we gathered on the beach for coffee, Scott reviewed the running order and ideal time to run Mule Creek and Blossom Bar.

After breakfast we broke camp, stowed gear, and pushed off one at a time. In just a few miles of rowing and fishing we reached our staging point at Rogue River Ranch. We pulled up on the long sandy beach for final equipment checks and to make sure our boats were “rigged to flip,” river-talk for having rods and loose gear stowed, dry bags tied down, and spare oars made accessible. We launched and then rowed the slow approach to the slot canyon.

The river current starts moving quicker as the elevation drops, and finally we saw the two boulders that mark the entrance. We call them Jaws. They stand like sentinels, three stories high. Once we passed them we really started to fly. Low water made the descent into the canyon steeper and faster than I’ve ever seen it. The walls felt tight, too close for comfort. I shot through the first section, and in several places the tips of my oars touched both sides of the canyon.

The line through Mule Creek is constantly shifting as the current rushes through the chute and bounces off the walls. To avoid crashing into the wall, you have to read the current and the waves bouncing off the boulders to anticipate what effect they will have on the boat. It’s critical to keep the nose of the boat pointing at the wall or boulder you expect to smash into so you can pull back away from it. Midway through the run, at one of the fastest points on the whole river, I misread the current and got thrown against the right wall. The rocks could have sideswiped the entire length of the hull, but just before impact I extended my right oar to protect the boat. The oar took the brunt of the damage and the loud scraping sound of wood on rock echoed off both walls.

I was fast approaching the narrow point in the canyon where all that raging water gets squeezed through an opening only little wider than our boats. It was where the metal drift boat had been wedged a week earlier. I took a deep breath. There was no margin for error or hesitation; I read the current, lined up the bow, had just enough room to give one hard forward row with both oars before tucking them in, and shot right through the skinny opening clearing both sides with just inches to spare.

Coffee Pot is the last of the nasty obstacles in the canyon. It’s a boiling, angry ogre of an eddy that lurks in the canyon. It’s about the size of a living room with a narrow opening and a narrower exit. Once your boat enters the eddy, the strong current sweeps everything counterclockwise and you can only exit when a rotation takes the boat close enough to the exit for a quick stroke of the oars to break through the current and slip though the opening. I’ve taken as many as five rotations before getting out of that eddy.

As I approached it, I was still moving fast in tight quarters, and I lined up the boat as best I could with my bow pointing slightly left of center. I gave a quick thrust on the oars to stick my bow inside the swirl. The current grabbed hold and pulled the rest of my boat onto the dance floor, and just as the stern had cleared the entrance and the whole boat was in the eddy, I gave the left oar a hard pull and spun the boat so the transom was lined up with the exit then gave both oars a deep pull and shot backward through the exit in the cleanest and quickest exit I’ve ever made in the Coffee Pot. I was through and I was pleased. My heart raced.

We all made it safely through Mule Creek, but there was no time to celebrate. Blossom was right around the corner. We pulled in at the steep rocks above the rapid, tied our boats off, and scrambled up the scout rock for the view of Blossom Bar to make sure there were no obstructions that might block our path or alter our line. It was one of first times in years there wasn’t an overturned raft, a metal frame, a busted-up drift boat, or a half-submerged kayak to maneuver around. After crawling back down the slippery rocks to the boats, we arranged ourselves in the same running order as in Mule Creek and floated single file to the top of the rapid in what seemed like slow motion.

As I pulled into the soft water of Purgatory Eddy just a few yards before the first pour-over of Blossom, I did one final visual check of the boat and then eased back into the current. Just before dropping over the entry point, I saw a sharp rock right in the middle of the pour-over that I had never seen before. I gave a quick corrective pull on the oars and missed it by inches. The strong current tried to pull me down to the four sharp, pointed boulders that rise up out of the water and form the barrier known as the Picket Fence, but I broke through the lateral wave and swung my boat across the current to the right so I could hook the boat around a rock we call the Horn and slip down the chute known as the Beaver Slide. At this point we are moving our boats laterally through an opening that always feels like it’s a size too small for our boats. To do it right, the bow must come very close to the pour-over that tumbles into the Picket Fence; this move requires steady nerves and a few strong pulls on the oars.

Scott Vollstedt

Scott VollstedtThis holding eddy just below the Picket Fence on Blossom Bar is where we position ourselves as the first line of safety in case of emergency for rowers that come after us. This photograph, taken in 2013, shows the river at normal water levels. In 2015, the water was several feet lower and the passage through Blossom all the more dangerous.

At normal water flows, I’d be so close to the left rock when entering the Beaver Slide that I’d have to raise my oar up out of the water and drop it on the other side of the rock to make the quick pivot. But with the water so low, the move I’d made 100 times before didn’t work. The rock was too tall for me to get my oar up and over, and there was a moment of panic as I had to improvise my entry and pivot down the slide with my right the oar, the only one I could use. As soon as I passed by the boulder and I could use both oars, I made the pivot and dug the oars deep in the water to break left out of the current. I made a series of zigzag moves through a dramatic rock garden filled with large and small rocks with names like Volkswagen and Clam Shell. I felt like a pinball going through the gauntlet of moss-covered rocks, swirling eddies, and boulders.

Greg Hatten

Greg HattenThe Class-III Devils Staircase was one of the few rapids we found a little easier in low water; it was a slip-and-slide run of moderate waves. I pulled into the peaceful eddy on river left to watch the rafts come through after me.

When we were all safely through the Class IVs, we had a traditional toast in the calm pool at the bottom of the rapid we call Whiskey Eddie and then we ran Devil’s Staircase, the last of the Class IIIs. From this point in the adventure, we normally turn our focus to fishing, but the low water wouldn’t let us get too comfortable. In a tricky Class II called Tacoma, one of my friends wedged an oar between two submerged rocks and had to let it go. The mishap almost sank his raft, and he was lucky to only lose some fishing gear and the oar. It could have been much worse.

Greg Hatten

Greg HattenOur last night on the river was a rocky camp site but a good one. My folding cot kept me elevated just enough so I hovered just above the rocks and slept comfortably in my old-school wool blankets and cowboy bedroll.

At our last camp we dined on fresh steelhead cooked over an open flame, cold wine, warm whiskey, and recalled the heroics of the boats, the nerves of the oarsmen, and the skills of the fishermen. Our release from the stress of rowing so many difficult rapids in such low water turned the evening into a celebration, and there were times we laughed so hard we cried. Night came to the Rogue, and we slept under a covering of stars.![]()

Greg Hatten is an outdoor writer, a consultant for active-consumer products, and a licensed Oregon Outfitter and Guide who hosts outdoor river adventures in a hand-crafted wooden drift boat pursuing steelhead on the fly.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Awesome article. And great video. What are the dimensions of the boat and what style McKenzie is the boat? Is it one of Greg Tatman’s boats?

Greg is out running another river so I’ll fill in for him for now. He wrote about his boat, OBSESSION, in 2015 Small Boats, our print annual. He describes his boat as “a traditional McKenzie-style drift boat” that he built using plans from a company no longer in business. In his article he offered drawings and dimensions of a boat similar to his. That design was by Roger Fletcher, author of Drift boats and River Dories. It has a length of 15′ 3″, a beam of 6′ 6″ and 4′ width across the bottom.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor

Thanks, Christopher. I just got off the Owyhee in Eastern Oregon—spectacular river for a wood boat. All those specs are right on the money and, yes, it’s a Tatman plan. I love the lines of this boat and the performance.

Excellent! I am currently planning on building my second boat, and yours is a beauty.

Thanks, Austin.