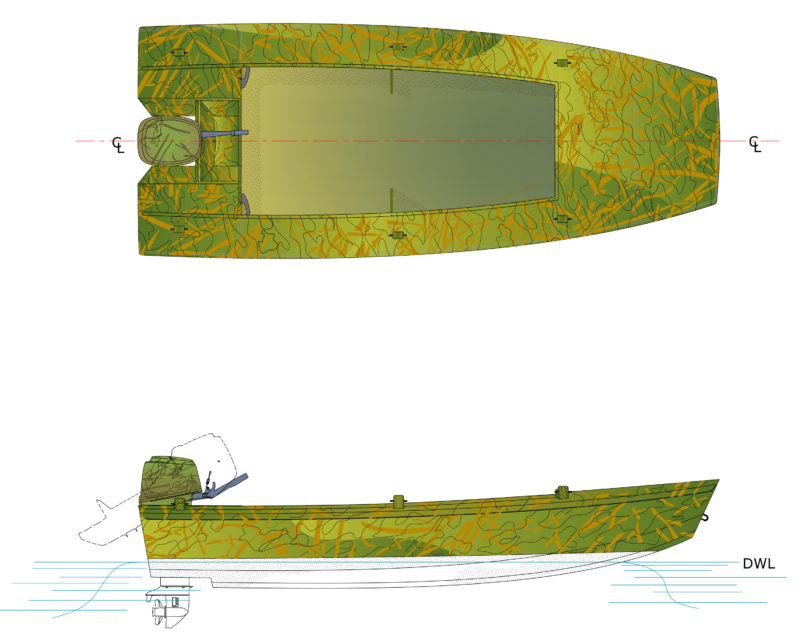

Sam Devlin’s Cackler wears camo well, but if hunting’s not your thing, it can easily take on a different look and different duties: Its 14′4″ garvey hull and unobstructed cockpit are eminently adaptable. Sam recalls: “I did the original work on the Cackler design years ago—about 1984—and did the design as a combination shop skiff and hunting skiff. The evolution was directly from my other duck-boat designs, with higher freeboard but retaining the decking that gives the reserve buoyancy and seaworthiness. A garvey-type hull allowed easy walking off the front of the boat when beaching, and effectively gives a larger volume to the interior without additional and unusable length. With the first one built I knew, in my humble opinion, that I had a winner.”

The Cackler I spent some time with was built at Devlin Designing Boat Builders for one of Sam’s regular customers, John Heater, a 95-year-old Bainbridge Island, Washington, man who has owned four other Devlin boats ranging from a 9′6″ skiff to a 31′ cabin cruiser. “In his more than 25 years of owning Devlin boats, John’s boating needs have changed over the years,” writes Sam, “and with this latest build he really wanted a small and fast boat that would be seaworthy enough to keep him aboard in all kinds of weather and conditions and would allow him to explore the Puget Sound waters around his island home safely.” Meant to be seen and enjoyed rather than concealed in the marsh, John’s boat looks good in gleaming dress whites.

photographs and video by the author

photographs and video by the authorAt rest, the Cackler offers a stable platform for fishing or hauling pots.

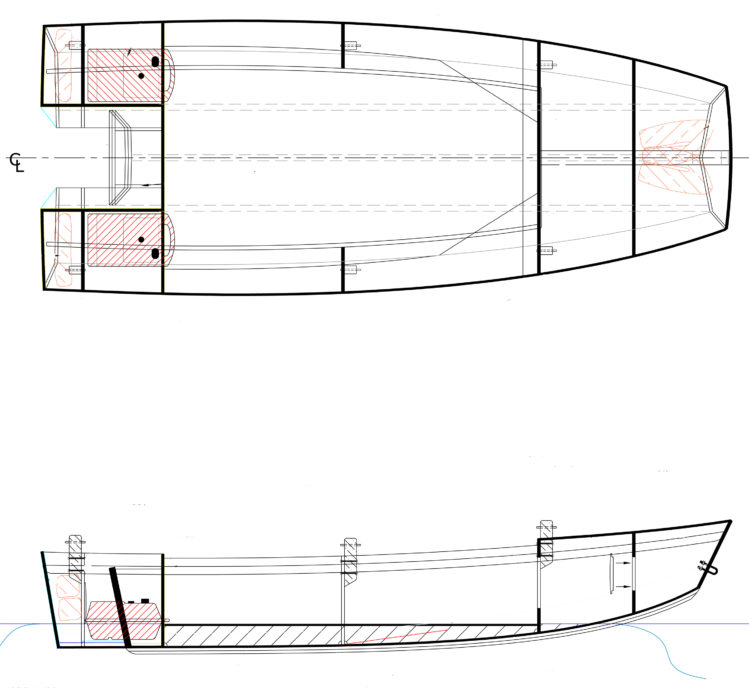

The Cackler, named after a species of goose with a distinctive call, has a simple garvey hull—two bottom panels, two side panels, and two transoms. Parts are CNC-cut from 1/2″ and 3/4″ BS1088 marine plywood, joined into full-length panels with interlocking puzzle joints, and assembled in the stitch-and-glue manner that Sam developed for all of the boats he has designed. The hull has a shallow-V bottom from bow transom all the way aft, and a pair of 1 1/2″ x 1 1/2″ bilge keels stiffen and protect it. A pair of wedges added at its trailing edge help keep the bow down when running at full speed.

There are three options for mounting the outboard motor: directly on the transom (the option offering the best speed), on the bulkhead at the forward end of the aft deck, or on a mount installed halfway in between. If there’s any fussing to do with the outboard, having it mounted in one of the forward positions provides a place to work on it without hanging out over the stern; according to Sam, this position also offers a profile less apt to make waterfowl nervous—especially late in the hunting season. The boat shown here was built to have the motor mounted in the middle. The arrangement provides a compartment between the mount and the bulkhead for a battery to power the electric starter.

Two 6-gallon tanks each have their place under the aft decks. The scuppers at the aft end of the cockpit sole drain water into a splashwell.

Under the decks in the aft corners are two compartments designed to take a pair of 6-gallon fuel tanks. Aft of those compartments are enclosed buoyancy chambers accessible through watertight deck plates mounted on the vertical bulkhead at their forward ends; inside each flotation chamber are two or more Type II personal flotation devices (PFDs). They’re strapped up against the deck, keeping them from sitting in any water that might find its way into the compartment. The PFDs provide readily available and inexpensive closed-cell foam to meet a Coast Guard requirement for positive flotation. Sam had tried other types of foam in the compartments—two-part pour-in foam and blocks of solid foam—but neither would survive an accidental exposure to gasoline. There’s a third buoyancy chamber under the foredeck that contains another four PFDs. A storage area aft of that chamber occupies the remaining space under the deck.

The plans call for six 2″ x 3″ hardwood bollards set around the cockpit coaming, a versatile arrangement for a workboat, but John’s Cackler has a full complement of stainless-steel deck hardware, including a single stout bitt bolted through the foredeck and into a broad carlin and a wooden backing plate.

The folding chair is the owner’s concession to comfortable seating. When not in use, it tucks under the foredeck, out of the way.

The 8′-long cockpit sole is unobstructed. Limber holes forward and aft keep the water from accumulating and let it flow aft to a splashwell just forward of the motor mount. The water can be pumped out while the boat is afloat or drained when it is hauled out and the transom stopper pulled. The coaming is a couple of inches wide and can serve as a perch for the helmsman, though John, understandably, likes the comfort of a padded folding chair. In 2015 he asked Sam to rig his Cackler for wheel steering. “He loves the change;” Sam writes, “he doesn’t have to sit sideways to run a tiller and he can more easily keep his eyes on the waters ahead.”

John’s Cackler has a bright white Awlgrip finish that’s so smooth and glossy it would be easy to think the boat was built of fiberglass and gelcoat, popped out of a production mold, and buffed to a high shine. Along with the sparkling hardware, it’s a far cry from the olive-drab and camouflage paint jobs the hunting versions get.

A 25-hp, four-stroke Yamaha provides the power for John’s boat; the Cackler will take up to 35 hp. The recess in the stern limits the turning range for the motor, but probably only a hair more than the 35-degree swing to either side that’s built into the motor. I wouldn’t expect better maneuverability: At low speeds with the tiller hard over, the Cackler did 360s within a boat-length radius. With a quick twist of the throttle to full power, the boat gets up on plane in 3.5 seconds. Push-button trim on the outboard adjusts the attitude of the boat for optimum speed. With just me aboard, I peaked at 22.2 knots. In turns, the boat banks without surprises, and I never felt that the hull was moving out from under me. The wide bottom offers a feeling of stability at speed and at rest.

When I cut the throttle suddenly and coasted to a stop, the wake would catch up and nudge the stern, but none of the slop washed aboard. I found backing a bit tricky. The shallow-V underbody doesn’t offer much resistance to lateral movement and once the bow gains some sideways momentum, it keeps drifting. Putting the tiller hard over to counter that only makes the boat sideslip. With more weight forward, the bow would have more water to reduce the lateral drift, and with more practice I’d learn to steer with a bit more finesse, avoiding the oversteering that’s likely the source of the problem.

Designer Sam Devlin puts the Cackler up on plane on Eld Inlet, his home waters at the south end of Washington’s Puget Sound.

You can order a Cackler with a host of options for hunting: a camo cockpit and engine cover, layout boards to give a hunter a comfortable seating position with a low profile, brackets for a cockpit blind, and a grassing skirt system to conceal the hull behind a fringe made of baling twine. If you opt to build a Cackler from a kit, you’ll get plans, instructions, and a 4′ x 8′ pallet with all of the plywood parts for the boat and for a building frame. Everything is accurately cut with a CNC machine, assuring that the boat goes together in proper alignment. Fiberglass, epoxy, and dimensional lumber can be purchased separately from Devlin Designing Boat Builders or from local sources.

If you’d like a larger version of the design, Cackler has big-sister designs: the 16′ Snow Goose and the 18′ Honker. You can ease into building a Cackler by reading Sam’s book, Devlin’s Boat Building: How to Build Any Boat the Stitch-and-Glue Way, and by ordering a 1/4-scale model kit. It has all of the same plywood parts as the real thing.

If you won’t be going hunting with a cockpit crowded with hunters, dogs, and decoys, you can use a Cackler for lake fishing, salvaging driftwood logs, or even taking the kids water-skiing. You’ll have little trouble adding to the list.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

Particulars

[table]

Length/14′4″

Beam/5′10″

Draft/6.5″

Gross weight/265 lbs

Load capacity/805 lbs

Power/30-hp outboard

[/table]

Devlin’s Designing Boat Builders offers the Cackler as finished boat for $13,995 (base price), a hull kit for $2,599, and as study/paper/downloadable plans for $5/$85/$55.