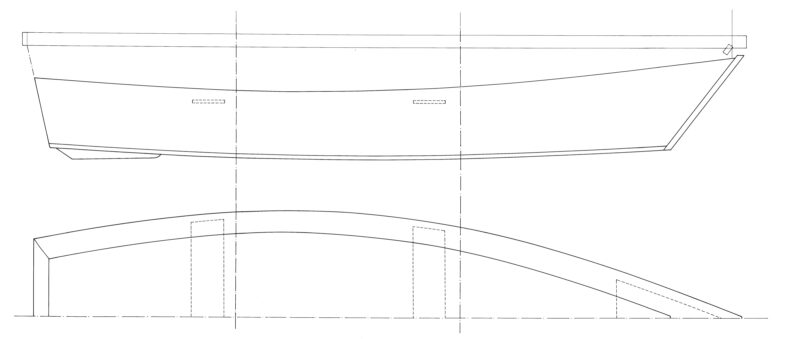

The 5.40m Flat Bottom Boat was designed in 1971 by Oyvind Gulbrandsen of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations for use on Lake Malawi in southern Africa. The plans are posted as a free design in their Fishing Vessel Design Database. I built the United Nations Flat-Bottomed Skiff last year, when I was 16, and it has performed well, no matter the conditions on my home body of water, the Great South Bay, Long Island, New York.

The seven pages of metric-measured plans for this 17′ 9″ flat-bottomed outboard skiff include drawings for the transom, the two molds, and the stem, all of which are straight-sided. The plans mention only some of the materials used in the construction—screws and galvanized nails for fastenings, and cotton caulking and bitumastic compound for sealing seams; the wood is given in dimensions only, not by species. That was only a minor inconvenience, as it didn’t take me long to find the wood I needed from local sources. For every structural member—transom, stem, frames, keel, and keelson—I used oak; for the side and bottom planking I used pine. Wherever the plans lacked detail, I turned to Pete Culler on Wooden Boats and Howard Chapelle’s Boatbuilding.

Liam McEvoy

Liam McEvoyFor a first-time builder the 5.40m is a straightforward project using easily sourced materials. I built mine in the driveway using pine for the planking and oak for the structural members.

Construction of the skiff is straightforward; no lofting is required and the 20mm (3⁄4″) planks need no spiling. The boat is built upside down. The 150mm x 20mm (6″ × 3⁄4″) sheer planks, installed first, and the two strakes that follow, are all straight, parallel-sided, and butted edge-to-edge. The 200mm-wide (approximately 8″) garboards are installed last and are butted against the preceding planks—straight edge to straight edge. On their other side they are trimmed down to the chine curve, established by the transom, molds, and stem.

The side planking went quickly, but when I had built to the last plank, I was presented with a serious problem. Where I should have been able to fit an 8″ garboard—as suggested by the design—I found that I would need a plank that was 12″ wide at the bow and 3″ in the stern. That, unfortunately, was far wider than any board I had to hand. I had unwittingly used nominal 1×6s where the metric plans called for 20mm × 150mm, or actual 1×6s. As a result, the three planks I’d used on each side ended up spanning a total of 3 3⁄4″ less space than they should have. Of course, I only discovered this after I had installed the sheer and topside strakes. I scrapped the initial plan and, instead, used a 1×6 for the garboard and filled the voids at the bow with wedge-shaped planks, known as stealers. I would recommend this method for builders who only have access to narrower planking stock. The stealers worked beautifully; their sharp and vulnerable aft ends are protected by the oak chines, which were installed after the planking was complete, and were beveled flush with the garboards prior to planking the bottom.

Margaret McEvoy

Margaret McEvoyThanks to her generous freeboard and frames that don’t span the bottom, the 5.40m is deep and roomy. The only leaking on launch day was through a poor fit between the transom and its adjoining bottom plank. I left the chines long at the stern so I could use them as a step when getting back into the boat from the water.

For the bottom, I used conventionally dimensioned 1x4s in lieu of the wider 20mm x 150mm (3⁄4″ × 6″) boards noted in the plans. At the suggestion of a shipwright mentor, I used pine, which has worked well. The plans call for caulking all of the seams—topsides and bottom—and filling them with bitumastic compound. I used butyl rubber and light-cotton wicking, although if I were to build the skiff again I would go without the bottom caulking—to simplify and speed the installation of the cross planks—and instead rely on tight edge-to-edge joints. The cross planking has not leaked; the only leaks have been from a poor fit between the transom and its adjoining bottom plank.

For a quicker build, the bottom could be of plywood, either canvased or fiberglassed. This would have the added advantage of being immediately watertight without needing to swell.

The plans call for a dozen frames that span the side planks from the chine to the sheer on each side; they do not span the bottom, which is left unobstructed. For fastenings, I used 2″ marine-grade stainless-steel screws instead of the galvanized nails suggested in the plans. They were more expensive but well worth it for the improved strength and corrosion resistance.

Margaret McEvoy

Margaret McEvoyThe 5.40m is designed with thole pins for both rowing and sculling. The high freeboard does mean that the boat is not easy to row in any wind above about 10 knots, but it’s good to have the option of the back-up propulsion.

The plans show only two thwarts and a small foredeck, but the simplicity of the 5.4 lends it to custom outfitting. I intend to switch from a tiller-operated outboard to a center console, which should be easily built and installed. The plans specify a maximum of 6-hp for any engine, but with a few simple structural changes the skiff can handle more. For example, to accommodate my 10-hp two-stroke engine I added knees, brackets, and braces to the transom and made the chines from 1 1⁄4″ stock instead of the 20mm (roughly 3⁄4″) stock called for.

I built the boat as a two-month after-school project that took around 140 hours of work. The materials cost $800, and the outboard cost another $800—not a lot of work or money for an 18′ powerboat.

I haven’t yet had to trailer the skiff, but a trailer with adjustable bunks for the bottom or a flat-bed with some dunnage (to account for the boat’s rocker) would fit the bill and take advantage of its flat bottom.

Margaret McEvoy

Margaret McEvoyLike the molds and transom, the stem is straight-sided. As per the plans I caulked all the seams with cotton and butyl rubber. The skiff could also be built of fiberglassed plywood, which would likely result in a quicker but more expensive build.

The 5.4 can be rowed, and tholepins indicated on the drawings are handy, even though the high freeboard, which makes the skiff a great motorboat, can make it hard to row in a stronger head- or crosswind. In calm conditions, it can move along at around 4 knots under a single pair of 9′ oars, but even as little as a 10-knot breeze can make for some hard rowing. The real value of the oars is as backup to an older, unreliable outboard; indeed, they have gotten me out of a fix or two when the engine has sputtered and died.

In the short, choppy swells of shallow waters, such as those in Great South Bay, the 5.4 is an able boat. It can handle up to 3′ whitecapped swells—if I’m smart about it—but a protracted battle with 3′ breakers is not fun, and I have learned that it’s best to stay ashore on such days. The boat is a match for 2′ waves and in 1′ waves can provide a comfortable ride.

Margaret McEvoy

Margaret McEvoyEven in a strong wind and choppy seas, the 5.40m has proven very stable and it tracks well. It can handle up to 3’ waves and in 2’ or lower waves provides a comfortable ride.

In suitable conditions the 5.4 is very stable and tracks remarkably well. With my long-shaft outboard it draws 8″ with the engine down and 4” with the engine up. Because of the shoal draft, I have rarely operated in the channels with the rest of the boat traffic, but instead race over the shallowest of sandbars. Since launching the boat, I have been more than happy with its performance. It handles my local waters well and provides a safe and steady ride even at its modest top speed of 10 knots. The 5.4 is a handsome, seaworthy vessel and a simple project for a beginning boatbuilder.![]()

Liam McEvoy lives on the south shore of Long Island, New York. He is grateful to his artist father and mother for teaching him about the beauty found in the old arts, such as sailing, classical music, and boatbuilding (as well as their tolerating the wooden boat in the driveway). He thanks Bob Hillman, an 86-year-old woodworker and owner of several wooden boats, who guided him through building the 5.4 and after whom he named it, HILLMAN. Liam is hoping to build more boats and has recently set up his own website for Clam Island Shipwrights.

5.4m Flat-Bottomed Skiff Particulars

Length: 5.4m (17′ 9″)

Beam: 1.68m (5′ 6″)

Depth: 0.49m (19′)

Displacement: 388 lbs

Power: 4- to 6-hp outboard

The plans for the 5.4m Flat Bottom Boat, and others, are available as free downloads from the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us your suggestions.

Thoroughly enjoyed your account of building your boat and operating it.

Good job, Liam.

Nice to see youth working with their hands crafting something of material and personal value.

Very nice article, with clear pictures that support it – thanks! I’d think a plywood bottom, reinforced with fiberglass, would be a great alternative to cross planking, and would make the bottom much stiffer – indeed the boat much stiffer and less prone to twisting – as well. Another boat of this type which may interest you is the Clarence River Dory, designed by John Welsford, here: https://duckworks.com/clarence-river-dory-plans/

Look forward to great things from you and Clam Island Boatworks!

Well done!

I built a sailing dinghy for use in those waters back in the eighties. I also sailed a 20′ sloop there in the nineties, I know how choppy it can be. Good luck in all of your future endeavors!