In August 1947, Cliff McKay Jr. was 12 years old and living in Clearwater, Florida. He and his friends spent most of their free time in and on the water, swimming, playing in rowboats, and fishing. For a year and a half, he had also been sailing after being invited by a couple of young men to sail on their Snipe. As the sailing bug took hold, Cliff’s father, Major Clifford A. McKay, had an idea. “Dad wanted every kid in Clearwater to have the fun and excitement I was having,” says Cliff. “He decided we needed to come up with a boat that would cost no more than $50 and get local merchants to sponsor them. It would lead to kids gaining independence, responsibility, and self-confidence.”

Major McKay took his idea to the Clearwater Optimist Club, a newly formed branch of Optimist International, a youth service association founded in 1919. “Dad was a promoter, in a good way: he could take an idea and make it happen, and everyone would be happy.” And McKay didn’t think small. At his first meeting with the Optimist club, he not only proposed the sailboat but suggested it could lead to “a sailboat competition for Juniors leading to a national competition or regatta in Clearwater.” The members asked McKay to find a designer. He went straight to Clark Mills, a local boatbuilder known to all as “Clarkie.”

Courtesy of Cliff McKay Jr.

Courtesy of Cliff McKay Jr.In 1947, Cliff McKay Jr., then aged 12, sea-trialed the prototype Optimist pram in Clearwater, Florida, and declared it to be “really great.”

McKay’s design brief for Mills was for a boat that could be built from two sheets of 4 × 8 plywood, use a bedsheet for a sail, and cost no more than $50. “Dad was no sailor, and Clarkie told me later that he talked Dad out of the bedsheet,” says Cliff, “but it may have given him the idea for the shape of the sail.” Writing of the experience many years later, Mills said it took him a couple of nights to come up with the design. “I drew lots of sailboats,” he wrote. “The problem […] was the price. Every time I had a nice little sailing skiff drawn, it figured out [to] too much cost. I finally cut the bow off, making it a butt-headed pram.”

In less than a week Mills had built a prototype. “I hauled it down to Haven Street Dock in Clearwater,” he said, “and Cliff McKay Jr. got in and took off in about a 20-mph breeze. He scooted out into the bay on the wind, off the wind, across, and then reached back to the dock. He landed saying, ‘That was really great!’”

Cliff recalls, “It was lively and accelerated smartly as the sail filled. It turned sharply when I put the tiller over. The bow didn’t dig in. It seemed to lift and skip across the water. The low sprit rig and generous beam gave it good stability. It was fun and easy to sail. The Snipe I’d been sailing was challenging, but the pram responded more quickly and was more fun.”

McKay and Mills took the boat to the next Optimist Club meeting. Fifteen sponsors signed up that night and the number was quickly doubled. In November 1947, the first official race was held with a fleet of eight competing off the Clearwater Yacht Club basin. By the following spring the club was hosting weekly races for boys and girls.

Jenny Bennett

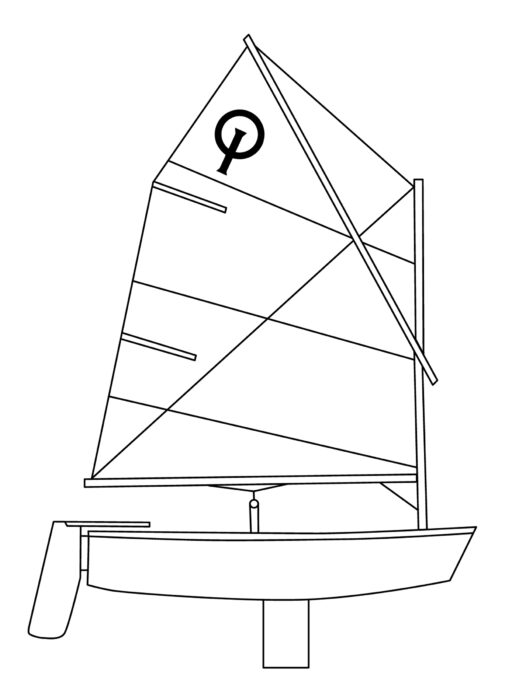

Jenny BennettToday’s International Optimist Dinghy has a sail shape modified from the original, is typically built of fiberglass, and rigged with aluminum spars, but the boat is still instantly recognizable as Clark Mills’s Optimist pram.

By 1949, there were more than 30 Optimist Prams. Then disaster struck. On the night of April 20, the old fish processing factory behind the yacht club, which had long served as the boat-storage shed, burned down; 29 of the prams were lost. Cliff says, “the fun and excitement of a year and a half vanished overnight. When the ashes cooled a few days later, I poked around looking for metal fittings from my boat. All I found were melted blobs.”

What might have been a tragedy was perhaps the savior of the Optimist class. The local radio newscaster ran a piece asking listeners to come forward to sponsor new boats. “In less than two hours,” Cliff recalls, “generous merchants and friends had pledged funds for 43 new boats, and $5,000 in building materials.”

News of the fire and the community response spread, and the Optimist Pram spread with it. According to Cliff, within seven years there were more than 1,000 Optimists racing in Florida. The class also grew quickly in Europe when, in 1954, Axel Damgaard took one of the prams to Denmark, made some modifications—most noticeably to the sail shape—and promoted it locally as the Optimist Dinghy. By 1965, the International Optimist Dinghy Association (IODA) had been founded with Austria, Denmark, Finland, Great Britain, Norway, Sweden, and the U.S. being the first members, joined shortly by West Germany and Rhodesia (today’s Zimbabwe). The first World Championships were held in the U.S. in 1966—less than 20 years after McKay had presented his idea in Clearwater.

Jenny Bennett

Jenny BennettThe early prams carried no additional flotation, but when fiberglass models were introduced, some were built with buoyancy tanks. Today’s standardized boats carry three buoyancy bags—two forward and one in the stern.

The Optimist Dinghy is a phenomenon in the sailing world. This simple sprit-rigged 8′ pram is thought to be the most numerous one-design boat ever. More than 100 national sailing associations belong to the IODA, and in 2000, 59 nations took part in the World Championships—believed to be a record for any Class Championship. It has been the starter boat for millions of children around the world and continues to be the most popular of all kids’ sail-training dinghies. And, while there are currently more than 150,000 registered boats, it is believed that well over 400,000 have been built.

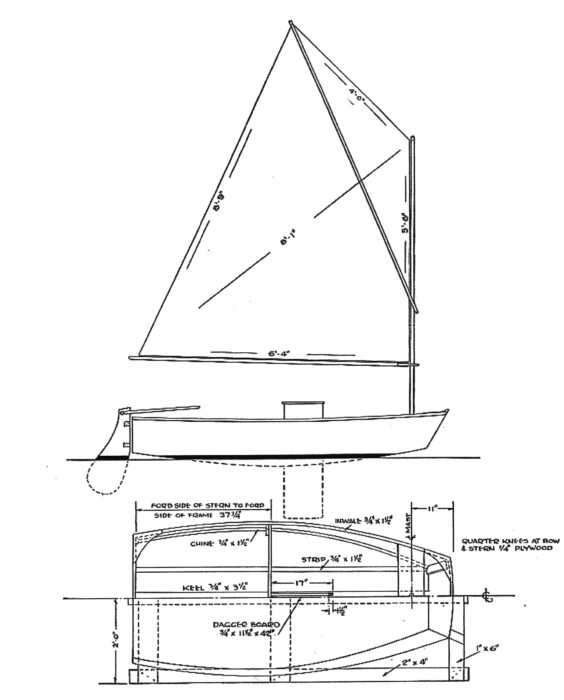

As designed by Clark Mills, the Optimist Pram could not have been simpler: 7′ 8″ long, 3′ 8″ wide with a slight rocker to the underwater shape, transom bow and stern, a daggerboard, a rudder and tiller, mast, sprit, and boom, all of which fit within the length of the boat, and a 35-sq-ft sail. Maximum draft, with the daggerboard down, was 2′ 6″. There were no thwarts but a single frame aft of the daggerboard trunk, and a mast bench 11″ aft of the bow transom provided athwartship stiffness. Longitudinally, a 3⁄4″ × 3 1⁄2″ keel, along with chine logs, inwales, and two stringers either side of the keel, all 3⁄4″ × 1 1⁄2″, provided strength.

Until the late 1960s the dinghies were built exclusively in plywood, but in 1970 the IODA officially approved the manufacture of a fiberglass hull provided it was not “inferior to a wooden boat in regard to safety, strength, and buoyancy.” Multiple variations appeared on the scene around the world and while the IODA made numerous attempts to standardize the weight and number of laminates of the fiberglass hulls, the struggle to retain control of construction and design plagued the association for years. Wooden boats continued to be competitive, but among training programs, the fiberglass hulls quickly gained popularity for their affordability and apparent indestructability.

Jenny Bennett

Jenny BennettThe one-design rules lead to large fleets of nearly identical boats. Variations are essentially limited to boat names and color of buoyancy bags and sail numbers.

In 1983, the IODA took a stand and announced that in order to create and protect a truly one-design class, the technical committee had chosen “a single-walled hull with a double bottom.” The official design was based on the “Winner Optimist” developed by Henning Wind, a Danish competitive sailor turned small-boat manufacturer, and introduced buoyancy with two bags placed either side in the forward half of the boat, and a third against the stern transom.

Within a decade the wooden boats had been surpassed and in today’s global fleets there remain few wooden hulls, and none take part in the competitive circuit. Today’s boats are, however, little changed from Mills’s Optimists. Overall length has grown by 1″, the draft has increased by 3″, and the sail shape has changed to include more roach requiring two battens—the sail area is still officially 35 sq ft. But the boat remains instantly recognizable as the pram from Clearwater. “My wife and I have visited harbors across the world,” says Cliff, “and there they are. You can’t miss them. We cruised into Madeira and almost the first thing I saw when we went ashore was a rack of Optimist Dinghies. One time we came into Miami and there was an Optimist regatta underway. There were so many dinghies, you couldn’t even see the shore.”

For Cliff, the appeal of the boat was always about its performance. “From that first day,” he says, “I was impressed by how quickly it responded and how lively it was. And it’s pretty stable—that sprit rig keeps the center of effort low, and the beam is almost half the length of the boat. I don’t think I ever capsized a pram when I wasn’t intending to. Sailing at a young age,” he continues, “is a little scary at first, but once you get accustomed to it, it’s unique. It’s multifaceted: wind, current, strategy, and everything’s changing constantly. Optimists have allowed millions of children to experience the challenge and fun of that.”

Laura Harrington

Laura HarringtonAs sailors grow in experience and confidence, the Optimist continues to challenge. Hadden Brinegar, 13, has been sailing Optimists since she was 9, and was on Team USA in the Optimist class at Nieuwpoortweek 2024 in Belgium. She says she loves Optis “because I’m forced to be independent and rely on my own instincts and decisions. If something goes wrong or you have a bad day, you have no one to blame but yourself. But if you win, you get 100% of the glory!”

For today’s young sailors, not much has changed since the early days. The boats weigh just 77 lbs and children as young as six or seven working together can wheel a boat down a modest ramp and launch it without adult assistance. Rigging the boat is kept as simple as possible, and the setup brings a level of independence unfamiliar in most childhood activities; children rig their own fleets, helping each other where needed, the more experienced directing the less so, often with little or no adult supervision. Pushing off from a ramp or dock, a skipper will be seen, typically head down, making final adjustments, even while pulling in the mainsheet so that the little boat picks up speed, heels, and skims away across the water.

Daphne Walsh, Maine State Optimist champion in 2021 and 2022, has an obvious affection for the boat. “They’re really fun,” she says, “especially when the wind picks up. For taller kids in light airs they’re tough, and when you’re young in a boat by yourself it can be scary, but it’s good.” Now an instructor, Walsh also loves them as a teaching boat. Just about anyone, she says, can sail an Optimist: they’re simple, stable, and quick to respond, so kids pick up the basics fast. But as a sailor becomes more proficient, the boat becomes more challenging. “There’s so much to teach,” she says; “there’s rigging techniques, tuning, balance, trim…you can really get down to the nitty-gritty with an Opti.”

Jenny Bennett

Jenny BennettThe stability and responsiveness of the Optimist dinghy combine to make it a reliable boat for sail training. Children learn by doing simple drills like follow-the-leader or tacking “on the whistle,” and by sailing in fleets of mixed ages and abilities, newcomers learn by watching and copying their more experienced peers.

The worldwide success of his concept went largely unnoticed by Major McKay but, says Cliff Jr., “he was just so happy to see the kids all getting the opportunity to sail.” Occasionally the universal appeal would be hard to ignore. “During the Munich Olympics,” Cliff recalls, “they had a parade of tall ships. And swarming around them were 400 Optimist Dinghies. I was watching it on TV and called Dad to make sure he saw it. That was a special moment for us to share.”

Clark Mills once told Cliff Jr. that his famous design “looked kinda funny, but it sailed real good.” For nearly 75 years, Mills’s contribution to sailing has been much praised, yet he always maintained he was just the guy that Major McKay came to with an idea. It was an idea that not only introduced millions of children to sailing but also spawned many of sailing’s top competitors: at the 2012 Olympics it was recorded that 80% of skippers across the eight classes were former Optimist sailors.

Clark Mills, inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame in 2017, once described the Optimist as looking like a horse trough. Daphne Walsh likens it to a bathtub, but surely no other small boat has introduced more people to the joys of sailing than the Optimist Dinghy.![]()

Jenny Bennett is editor of Small Boats.

International Optimist Dinghy Particulars

LOA: 7′ 9″

LWL: 7′ 2″

Beam: 3′ 8″

Draft: 5″ (board up) /2′ 9″ (board down)

Weight: 77 lbs

Mast Length: 7′ 5″

Sail Area: 35 sq ft

Courtesy of Michael Jones

Courtesy of Michael JonesThe original Optimist pram as drawn by Clark Mills.

The modern one-design International Optimist Dinghy

With thanks to Cliff McKay Jr. for his memories, and to Michael Jones who provided a wealth of historical background.

In the U.S. a McLaughlin Optimist club racer starts at $3,835. Secondhand boats can be found for less than $1,000. For more information about the Optimist class, visit the International Optimist Dinghy Association. Plans are available from multiple sources including the IODA ([email protected]); ODTPlans, offering full plans with instruction booklet and drawings for the auxiliary jig and temporary frames; and the Cleveland Amateur Boatbuilding and Boating Society (CABBS), offering plans for amateur building redrawn from plans published in the 1950s.

Clark didn’t much like what happened to the Opti, preferring it to be home or simply built. I gather that he was invited to speak at some fancy Opti championship, let the folks know and wasn’t invited back. I don’t believe it is possible to build one accurately enough to measure into the International standard. There will be a first generation home built example in the new Wells Boat Hall that will open this summer at Mystic Seaport.