The small village of Gorran Haven lies on the south coast of Cornwall, U.K., and has an east-facing drying harbor partly protected by a seawall. Gorran Haven crabbers, the traditional working craft of the harbor, were small boats, usually between 16′ and 18′ long. They were worked by two men, or a man and a boy, and even singlehanded at times, for both crabbing and conventional fishing. They were typically straight-stemmed, with a long keel with much less draft forward to suit the slope of the Gorran Haven beach, hollow waterlines, maximum beam just aft of amidships, and a steeply raked wineglass transom. According to a mid-Victorian letter quoted by Cornish historian James Whetter, “The crab boats of St Gorran Haven are superior to any of the kind in the country, perhaps in the world.”

Debbie Purser, co-founder of Classic Sailing in St. Mawes, Cornwall, for several years has owned the 17′ Gorran Haven crabber OUTDOOR GIRL, a 2008 replica of ELLEN, built in 1882 by Dick Pill in Gorran Haven. ELLEN was reputed to be the fastest Gorran Haven crabber ever built and is now owned by the Cornish Maritime Trust. Debbie uses OUTDOOR GIRL commercially, taking guests on sailing and wild-camping trips—complementing the charters she offers on her 44′ LOD pilot cutter TALLULAH. When she decided that a second crabber, to be named WILD BOY, would be a welcome addition to Classic Sailing’s fleet, she was inspired to build a replica of CUCKOO, built by John Pill in 1881.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe seams in the traditionally planked carvel hull were caulked with linseed putty and red lead. The jib is hanked to the forestay with traditional bronze spring-clip hanks, and the forestay is shackled to the stemhead while the two shrouds are attached with simple lashings.

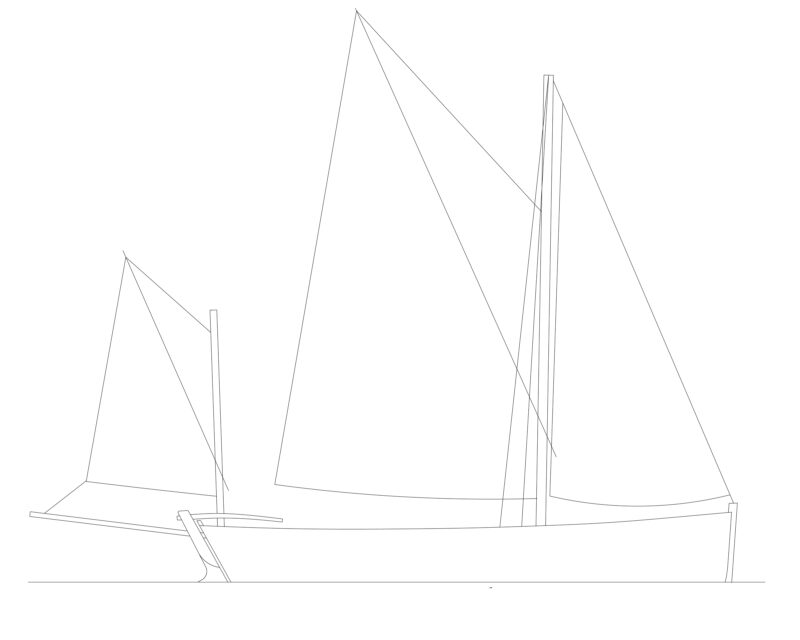

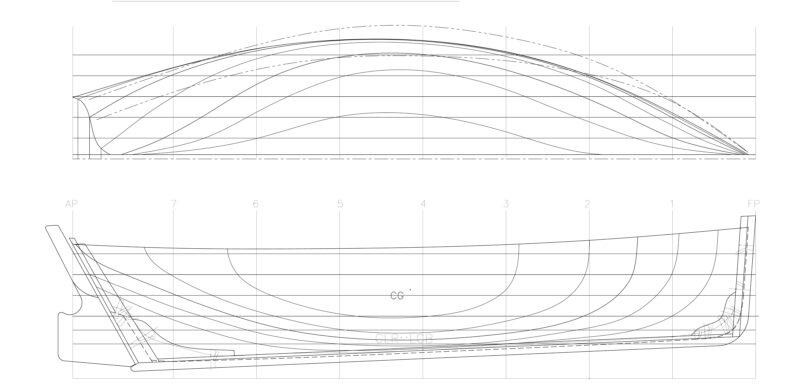

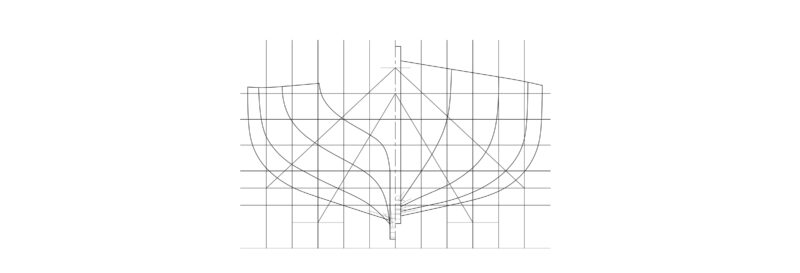

In his book Spritsails and Lugsails, naval architect and maritime historian John Leather described the CUCKOO as being “16′ 5″ long × 5′ 9″ beam by 2′ 6″ moulded depth, [with] a plumb stem and small, well-raked transom. She was undecked, built for rowing as well as sailing, with well rounded sections and steep rise of floor, which resulted in very fine waterlines at the ends […] Although centreboards were not used, the [crabbers] went well to windward due to the sharp bottom and large staysail though they needed reefing early in freshening winds.” The original CUCKOO no longer exists, but her lines were taken some years ago by Philip J. Oke and are now kept at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. They were also published in Inshore Craft—Traditional Working Vessels of the British Isles, by Basil Greenhill and Julian Mannering.

Debbie took the idea of building a new CUCKOO to Mike Broome, course tutor at the Boat Building Academy (BBA) in Lyme Regis, U.K., who says he “tweaked the lines to produce a fair set of lines and offsets,” and digitized them.

A second crabber is under construction at the Boat Building Academy. In this second build the planking is of yellow cedar and additional, larger frames were fitted to give the hull better strength. In all other details the two hulls are the same. The long keel, with its depth astern acting like a skeg, gives the boat good directional stability with minimal draft. The foot of the rudder is angled up from the keel so that it will not touch bottom if the boat is grounded.

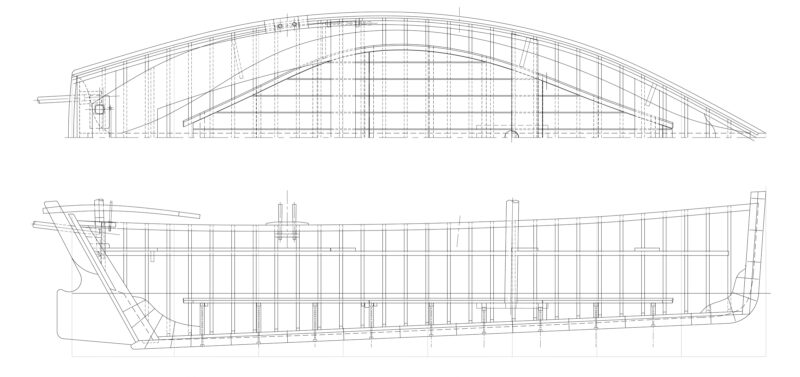

Construction started with the full-sized lofting and building the molds. Then came the backbone—keel, hog, inner and outer stem, and sternpost, as well as knees for the stem and sternpost; all in solid sapele—which was set right-side up on a temporary framework a couple of feet off the ground. The seven molds and the 1 1⁄4″-thick oak transom were fixed to the centerline, the former temporarily, and the latter permanently at an angle of 29° off the vertical. Ribbands were temporarily fixed to the outer edges of the transom, molds, and stem, and then the frames—7⁄8″ × 5⁄8″ at 8″ centers—were steam-bent inside the ribbands. (After WILD BOY was finished and taken home to sit on a beach supported by legs, a handful of the frames broke; in a subsequent build of a second Gorran Haven crabber at the BBA, the frames were sized up to 7⁄8″ × 3⁄4″ centered at 6 3⁄16″.)

With the frame complete, work began on the carvel planking. The sheerstrake was fashioned of oak, for its extra strength and resistance to wear, while the rest of the boat was planked in Siberian larch. There are 11 planks per side, with an additional stealer plank immediately above the garboard in the aft 7′ of the hull. The planks were cut from 10″-wide boards and, other than the garboards and stealers, all had to be scarfed and steamed to take the curves and twists at the bow and stern. The finished thickness of the planking is 5⁄8″, but to allow for the backing-out of the interior face of the planks, particularly at the turn of the bilge, some had to come from 7⁄8″ stock. The planking process started with the garboards and then the sheerstrakes. Thereafter, planks were fitted alternately—up and down—finishing each side with a shutter plank. The V-shaped seams—created by the beveling of the plank edges—were caulked with linseed putty and red lead.

The build process continued with the fit-out of the hull. Nine 1 1⁄4″-thick oak floors were fitted with their top edges level so they could also act as bearers for the sapele sole boards. The risers for the four 1″ oak thwarts are 2″ × 1″ oak. The aft thwart serves as a helm seat; forward of that is a removable rowing thwart, then the mast thwart, and finally a thwart in the bow for strength. The oak inwales and outwales are both 1 1⁄2″ x 1 1⁄4″ with a 4″-wide × 1⁄2″-thick oak cap with two scarf joints. The rudder is of 1 1⁄2″-thick solid oak, its blade made up of four biscuit-jointed pieces.

For the singlehanded sailor, the yawl rig with jib can seem daunting at first, but Debbie has her crabber set up so that all the running lines are close to hand. If the mizzen sail is sheeted in, it will act as a steadying sail, holding the boat up to the wind and allowing the crew to go forward to raise or lower the other sails.

The CUCKOO drawings in Inshore Craft do not include details for a rig other than showing short stumps to indicate the two mast positions, so Mike drew a spritsail-lug rig similar to the rig on OUTDOOR GIRL. All the spars are solid Douglas fir, with the 3 1⁄2″-diameter mainmast made from two pieces assembled longitudinally with opposing grain for stability. All the spars fit easily inside the boat except for the mainmast, which lays atop the boat from stem to rudderstock. While it is possible for a tall, strong person to step the mainmast singlehandedly, it is much easier for two people. Once the mast is upright, the bronze gate in the mast thwart holds it steady so that the shrouds can be lashed to the shroud plates; the forestay is shackled to a stemhead fitting. The mizzenmast and bumkin can both be easily stepped and rigged by one person.

On the day that Debbie and I went for a sail the winds were very light, but she was able to tell me about her experiences of sailing the boat. “She goes to windward amazingly well considering she hasn’t got a centerboard or [deep] keel,” Debbie said. “She points better than some other boats with centerboards, although in strong winds she makes a bit of leeway, and when tacking it is often necessary to back the jib to make sure the bow gets through the wind. We once managed to do 7 knots on a reach in quite a lot of wind with two people on board.”

There is plenty of room on board for a crew of three (or more if they are prepared to be close to each other) but the boat is also set up for singlehanded sailing, which Debbie takes advantage of quite often. The rotating jam cleats for the jibsheets are positioned so the helmsperson can reach them, and there is a bungee dampening system for the tiller so that Debbie can move forward to drop or hoist the sails; the bungees also can center the helm while she is rowing. In stronger winds—around 15 knots or more—she has found that she cannot hike out enough to make much difference to the heel and that the boat does make a bit of leeway as a result.

The crabber’s traditional pedigree is instantly recognizable from the wineglass transom to the capped gunwales, wooden thole and belaying pins, wooden blocks and spars.

Debbie has two rows of reefpoints in WILD BOY’s mainsail but finds that deploying the second reef is impractical as the bottom of the sprit is then too low and would need to be replaced by a shorter sprit. Nor has she found that brailing up the leech is practical as “there is still a lot of sail up. But it is great in no wind when you just want to get it out of the way to row.” (Because of its limited use, Debbie doesn’t always rig up the brailing line, especially if she’s going out for a short sail.) Although the boat weighs about half a ton with ballast and a crew of two on board, Debbie finds it surprisingly easy to row in light winds, and says that with the deep skeg aft, it tracks well. On one occasion, she comfortably rowed the crabber for about a mile in a flat calm.

Although Debbie has found it handy to be able to sail off a beach with just the jib and mizzen raised and then to hoist the mainsail when under way, she says that the overall performance with just those two smaller sails isn’t very good, especially to windward, “but it works [if I’m] taking inexperienced sailors out in a blow and [don’t want] to scare them.” With a draft of about 8″ forward and 15″ aft, Debbie particularly likes the ease with which the boat can be taken into a beach to offload gear, and she has found it relatively easy to get the boat on and off a trailer.

In light airs and with the sails trimmed, the crabber tracks well and, at times, will sail itself.

While clearly suited to day-sailing, the removable middle thwart and absence of a centerboard also means that the crabber offers plenty of space for overnight accommodation, when the sprit can be set up between the two masts as a ridgepole for a cockpit tent. There is no enclosed storage space or built-in flotation, but a foredeck could be added forward of the mainmast and buoyancy bags could be attached on the underside of the fixed thwarts.

With plenty of capacity for people and expedition gear, the Gorran Haven crabber is well suited to coastal exploration. The hull is seaworthy and can easily be trailered, and the traditional construction—while not for the inexperienced builder—isn’t particularly complicated.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boatbuilding and repair industry and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from schooners to dinghies.

Gorran Haven Crabber Particulars

LOA: 16′ 5″

Beam: 5′ 9″

Draft: 15″

Sail area: 134 sq ft

Plans courtesy of Mike Broome

Plans courtesy of Mike Broome.

Digital plans for the Gorran Haven Crabber are available from Mike Broome for £165.

Both Inshore Craft: Traditional Working Vessels of the British Isles and Spritsails and Lugsails are available used from multiple book dealers; Inshore Craft is also available as a Kindle from Amazon.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.