I keep a glued-lapstrake Penobscot 17 oar-and-sail boat on a mooring on the coast of Maine. For simplicity’s sake, we leave it uncovered. While that saves a lot of time fussing with a tarp, the downside is that when we get a big rain, the open hull collects water, and I need to bail her. Sometimes it’s just a few inches, but there have been times after a big storm when I have found a foot of water in her. The boat, built of wood and fitted out with plenty of foam insulation for flotation, is in no danger of sinking, but it can be a long chore to bail her out.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorAfter some big rains, I would find our Penobscot 17 filled to almost bench-level. The boat was never in danger of sinking, but it did lead to time-consuming bailing before we could get off the mooring.

I wondered if there was a better way to keep her bailed and if I might be able to cobble together a small solar-charged, battery-operated bilge pump with a switch. I have done a lot of basic wiring in our homes, but this seemed like a different sort of electrical knowledge. When I wandered the marine stores, the choices and options were overwhelming. Not having a great electrical mind, I didn’t know where to start, so I called a good friend who’s an electrical engineer and a fellow boater. He came across the EasyBailer online and suggested it seemed a good solution at a good price.

After I checked the site, I learned that the designer of EasyBailer, John Bianchi, had stopped making the units several years ago but now offers plans. The 22-page PDF I received from the EasyBailer website by return email was detailed with clear step-by-step instructions, advice, photos, and a parts list, which made the entire project seem doable. John had experimented with different pumps and switches over the years to find components that were the simplest and most reliable. I had most of the tools—pliers, crimpers, heat gun, drill bits—and I found most of the electrical connectors at a hardware or big-box store. No soldering is needed. The pump, switch, battery, solar panel, and a few of the electrical connectors were easily ordered online and all came from Amazon suppliers in one package. I did find an inexpensive bilge hose from Walmart that seems fine. John’s PDF has a complete list of materials with helpful details on how he determined the reliability of each component, which makes it evident that he experimented for years to find the best parts and arrangement. I won’t detail the process here because the PDF does such a good job of it. The unit can be built in an afternoon or evening. I spent about $160 in parts for my EasyBailer.

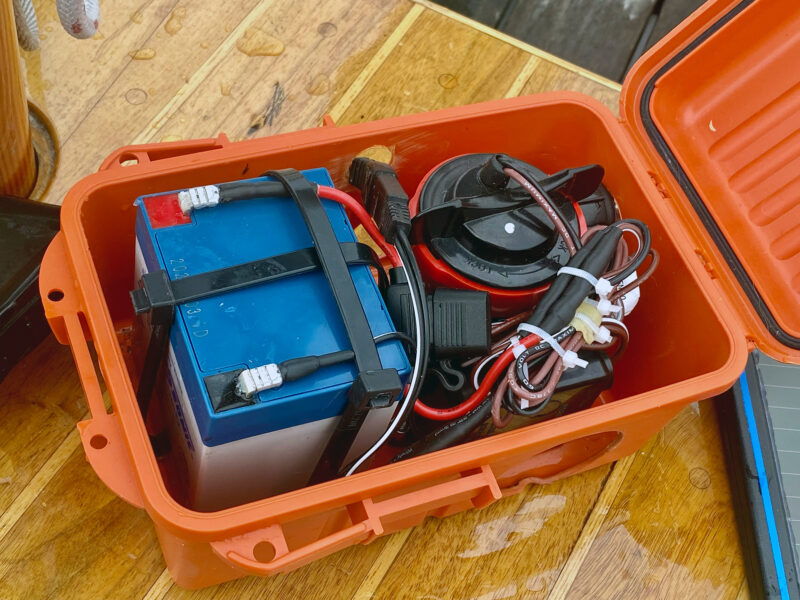

The assembled unit sits in a customized battery dry box. The switch can be seen beneath the bundled wires. On its face, not visible in this picture, is the activating panel that activates the pump when an electrical connection is made by rising water. The round hole cut in the side of the box allows water in to trigger the switch and gives access for manually testing the switch by touching its contacts. Dielectric grease is used throughout to ensure all the crimped connections remain water resistant.

When assembled, the components—pump, switch, battery, fuse, and all connections—are contained in a small dry box (approximately 7″ × 11″ × 5″). Altogether it weighs just a few pounds. The box specified in the plans is inexpensive, available online, and its main function is to contain the parts. The assembled unit is placed in the lowest spot in the bottom of the boat and the solar panel, which is connected by approximately 6′ length of wire, can sit anywhere that’s unobstructed. I use a short line to tie the bilge hose to the gunwale. When I want to row or sail, I stow the panel and hose with the pump box under the deck.

The pump is activated by 2″ of water and shuts off when there’s about 3⁄4″ left at the bottom of the EasyBailer box. When I first get onboard after a rain, I sit positioned so my weight pools the remaining water around the pump. After a couple of minutes, most of the remaining water has been pumped out; following up with a little old-fashioned sponge work mops up the rest.

The tiny pump specified by John is rated for 500 gallons per hour (8.3 gallons per minute) and moves a lot of water out of the boat quickly. He initially experimented with less expensive float switches but found that debris floating about in a boat’s bilge inevitably gets caught up in the switch, which can prevent it from turning the pump on. He specifies an electronic switch, which has two points that activate the pump when in contact with water (or one’s fingers to test).

The box holding the pump assembly sits comfortably in the maststep locker with the solar panel resting on the deck above. To make sure the hose end stays overboard while we’re not there, we lash it to a shroud.

I’ve only had a couple of small issues so far. My first solar panel apparently failed after a year or so: the red/green indicator light wasn’t functioning, and I couldn’t tell if the panel was charging or not. I bought another (approximately $20) and it has been working fine. The solar panel is a 1.8-watt trickle-charger that’s completely sealed to be waterproof, rugged, and durable (according to the manufacturer). John suggests putting a bead of marine-grade silicone caulk around the glass panel for extra weather protection. The other component I’ve considered replacing is the battery. John recommends a small, inexpensive, lead-acid battery. I’ve seen lithium batteries with similar dimensions that are far lighter and should have more power, but they are closer to $50 so I’ve held off investing in one. I’ve noticed that after a heavy rain the battery I have seems a bit weak: the pump still runs but sounds a little slower to me. I’ve not tested the battery to see how quickly it recharges.

John clearly states the unit is designed for bailing occasional rainwater from boats up to 17′ and not boats that leak and need constant pumping. I believe the EasyBailer was designed more than a decade ago, so it’s also entirely possible that solar panel and battery technologies have evolved and there might be more advanced alternatives. Even so, I think the basic concept and design are still solid, the instructions are applicable to materials available now, and it seems like a worthy investment for most small boats. It’s also a nice opportunity to learn something new and have a simple project to complete that is truly useful.![]()

Jim Root splits his time between a home in Barrington Hills, Illinois, and Round Pond in mid-coast Maine. He is now retired after a career in communications and advertising. He enjoys being out in either a Pygmy sea kayak, restored Old Town canoe, Hylan Beach Pea, or Penobscot daysailer. He also paddles two skin-on-frame Greenland kayaks, per Christopher Cunningham’s book. Jim’s mother says he has too many boats. He also paints and finds subjects in Maine and Illinois to fuel his passion for painting. You can see his work on his website.

Plans in PDF format for the EasyBailer pump are available from EasyBailer for a minimum $25 donation to prostate cancer research.

You can share your tips and tricks of the trade with other Small Boats readers by sending us an email.

Hi Jim. Nice article! I used an EasyBailer for about 10 years when I had my Alpha/Beachcomber dory moored in Round Pond. I bought it from the designer. It worked great, as you say, for most of the time. I think the older dory (at 21 ft) was pushing the bailer a bit too much. It worked fine unless there were several days in a row of rain and it couldn’t recharge the battery under the dark/cloudy conditions and keep up with the constant rain. Since the pump was adequate, the designer suggested a bigger battery with more storage capacity. That made the package a bit bigger, but it worked fine after that. A smaller boat should have no problem, and as you point out, the solar panels are probably better than 15 years ago also. Thanks for a great article on a very useful piece of equipment!

Hi Ken,

Just seeing your note here. Cool you’ve known of this for years. Makes sense what you say about scaling a battery up to the boat. I’m curious about newer lithium batteries being more powerful and lighter. The pump specified really moves a lot of water fast. So mainly just having enough power to do the job. And agreed, several cloudy rainy days would tax a small battery.