For 15 years the Everglades Challenge has pitted paddlers, rowers, and sailors against a variety of sea conditions on a 300-mile journey from Tampa Bay to Key Largo. The rules of the race require that every vessel be launched by hand from the beach. The 2015 EC brought some approximately 107 canoes, kayaks and small sailboats of every description to the starting line at Fort DeSoto Park near Tampa Bay, Florida. It would be my fifth Everglades Challenge and my first with Wally Werderich, a 42-year-old Chicagoan with a respectable ultra-distance racing résumé.

My first EC, in 2003, was a trial by fire. In that five-day journey my partner and I battled through navigational errors, leaking spray skirts, headwinds, waves, sleep deprivation, and hallucinations. In 2006 I teamed up with veteran WaterTriber Marty Sullivan and we picked a plywood triple kayak to race in. We spent two months building the kayak and one month training in it. The race went perfectly, and Marty and I finished in a time of three days and six hours, a Class 1 (Expedition canoes and kayaks) record that has yet to be broken. In 2009 and 2013 I raced with other partners in the triple, CONDOR by name, and again finished first in the division.

On Friday, March 6, Wally and I spent the morning at my house in Orlando making some modifications to his kayak seat and trying to fit all of our gear in my car. We loaded CONDOR, picked up my girlfriend Stacey, our shore contact, and arrived at Fort Desoto Park just in time for the mid-afternoon roll-call of racers. We all go by aliases. Back in 2001, when I needed to pick my WaterTribe name, my young daughter was a fan of Buffy the Vampire Slayer so I came up with RiverSlayer. Wally chose Los Humungos.

During the pre-race meeting, WaterTribe Chief, Steve Isaac, went over the protocols. The EC requires more safety gear than any other organization I’ve raced with. For electronics alone, Tribers have to have a GPS, EPIRB, SPOT satellite messenger, cell phone, and VHF radio.

Stacey Roberts

Stacey RobertsOver 100 kayaks, canoes, and sailboats lined up on the beach for the 2015 Everglades Challenge. The Sunshine Skyway Bridge in the distance spans the entrance to Tampa Bay.

Over 100 kayaks, canoes, and sailboats lined up on the beach for Everglades Challenge. The Sunshine Skyway Bridge in the distance spans the entrance to Tampa Bay.

Following the meeting Wally and I transported CONDOR to the starting line. The full length of the beach was filled by boats, more than half of them sailboats. The forecast was for 15–20-mph winds out of the northeast. Back at the hotel Wally and I put bananas, cookies, beef jerky, Snickers, protein bars, Cheez-its, fruit cups, and PB&J sandwiches in ziplock bags—small amounts that we could eat throughout the race. Around 10 p.m. we had finished and headed for bed.

The hotel alarm clock went off at 5 a.m. and we quickly mixed up our powder drinks and took our remaining gear to the Jeep. After a quick stop for breakfast, we headed for Fort Desoto. It was still dark when we arrived, but the beach was awash with headlamp-wearing racers making final preparations.

Stacey Roberts

Stacey RobertsIn the predawn light before the start at Fort Desoto Beach, Wally and Rod pack CONDOR with supplies and gear.

In the last hour Wally and I were able to fit all of our needed gear into CONDOR and Wally, donning a mask, cape, and tights like a Mexican Luchador wrestler, transformed himself into the great Los Humungos. I am all for having fun at the start; the suffering will come later.

At 7 a.m. there was no horn or gun signaling the start. Everyone just started pushing and pulling our boats to the water. The tide was low, and we had to haul across a sandbar offshore. With Wally seated forward and me aft, we were soon in deeper water and paddling away. Despite being in a kayak, Wally and I were both using lightweight canoe paddles—they’re less fatiguing than kayak paddles. I put the rudder down so Wally could steer, but in the rush to get under way, his seat had slid back and he couldn’t reach the rudder pedals. As a canoeist I don’t trust rudders: many kayakers get knocked out of races with various rudder malfunctions. I have plenty of experience steering CONDOR without a rudder, and we continued without any problems.

We expected rough conditions at the entrance to Tampa Bay, and about 2 miles into the challenge the wind and waves picked up. Soon we were surfing on 3–4′ waves. I was sure some of the less experienced Tribers would be having problems.

Stacey Roberts

Stacey RobertsThe race was still on as CONDOR passed under the bridge to Santa Maria Island.

Soon we were in much calmer waters and going under a bridge linking the mainland to Anna Maria Island. As we approached a second bridge I spotted Stacey, right where she’d always been on previous races, calling out to wish us luck. I told her we would call her from Checkpoint 1 at Cape Haze Marina, and we continued southward.

Tom Ray

Tom RayWith the wind blowing out of the east, the sheetless two-meter sail provided little help. For Wally, still sporting his Los Humungos attire, and Rod lightweight canoe paddles are the best choice for the long haul in the kayak.

About 15 minutes later a sheriff’s boat sped past us heading north toward the channel. Five minutes later a Coast Guard boat followed. Some of the Tribers must have been having a rough go of it, but Wally and I were making good progress; trailing a couple of the leading kayaks, but I expected them to slow down after the first day and then we could reel them in.

We were going under a bridge near Sarasota Bay when another racer’s shore contact standing above us called out that the Coast Guard had declared a weather hold and we were supposed to head to shore. Wally got Stacey on his cell phone; she told him there were multiple rescues in the shipping channel and the Coast Guard had ordered all racers to shore. This seemed rather ludicrous since we were surrounded by pleasure boaters and recreational kayakers enjoying a calm sunny day on the water. None of the lead kayaks had stopped, so we told Stacey that we’d continue to Checkpoint 1 and call her in a few hours.

We passed a few other WaterTribers. Some knew nothing of the Coast Guard order and others had new tidbits of information. Several hours later Stacey gave us the bad news: After rescuing a dozen WaterTribers in distress, the Coast Guard canceled the race and requested that racers proceed to Cape Haze Marina and make arrangements to be picked up. I told Stacey we would camp there before deciding what to do. I felt bad for Wally. He’d paid the entry fee, took time off from work, and traveled to Florida, only to have the race canceled.

Wally Werderich

Wally WerderichBill Whale, Tribe name “Whale,” with a reef zipped in his sail and paddle in hand makes tracks in his outrigger-equipped decked sailing canoe.

We pulled into Cape Haze Marina about 8:30 p.m. After changing into some dry clothes, I spotted Bill Whale (tribe name, appropriately, Whale). He had just arrived in his sailing canoe and had met up with Bob, a friend who lived nearby. Bob drove us to a restaurant and over dinner Bill, Wally, and I decided to continue to Key Largo. Bill was planning to take the Wilderness Waterway through the Everglades. It adds about 30 miles to the trip, but winds through some spectacular scenery. This was my first chance to paddle through the entire waterway.

Bob dropped us off at the marina with directions to his house, 2 miles south along the canal. Thirty minutes later we spotted him by his dock. I would have been happy to camp in his backyard, but Bob had several guest bedrooms available. After a shower I quickly fell asleep in a comfortable bed.

We were up at 6 a.m. Bob advised us that the winds would be gusting from the east and suggested that we paddle out into the Gulf through Gasparilla Pass to avoid the wind and waves of Charlotte Harbor. We took his advice and headed into the Gulf of Mexico before turning south. The tree-lined shore blocked most of the wind, and we had good paddling conditions. As we passed North Captiva Island, Bill was under full sail and Wally and I had to paddle hard to stay with him.

Wally Werderich

Wally WerderichMany stretches of water between the mainland and barrier islands were busy with boat traffic and offered no places to camp.

We turned east on a small channel leading to Sanibel Island. The inside route was crowded with motorboats, and we had to stop abruptly to keep from being run over by two speeding jet boats going at least 50 mph. We crossed paths with several Tribers in sailboats tacking back and forth as they neared the Sanibel Island bridge. One told us to watch out for the law: It seems another WaterTribe sailboat was stopped for “excessive tacking” by a police patrol boat and told to turn around.

Wally and I crossed under the Sanibel causeway while Bill went west to find higher clearance for his mast. We caught up with each other south of Sanibel Island. The sun was setting as we paddled by Estero Island. Bill suggested that we stealth-camp on Lovers Key, and two hours later we pulled our boats up there on a beautiful white sand beach. Lovers Key is a state park for day use only, but it’s the only undeveloped land in the area. As we set up our tents I noticed ATV tracks and hoped park rangers did not make nighttime inspections of the island. We were soon all inside our tents and asleep. We hadn’t been racing, but paddling 50 miles in a day is still tiring.

We were up and paddling by 6 a.m. Bill took advantage of the east wind and gradually sailed ahead of us. Wally and I paddled hard for about three hours and covered over 15 miles. We caught up with Bill as we approached Gordons Pass south of Naples. He suggested that we take a break at the park inside the pass. There was a lot of boat traffic, and a big catamaran sailboat suddenly turned in our direction. Wally and I sprinted out of the way; Bill had to turn around to keep from getting hit. When we finally made it to the park, Bill was still steamed about the near collision. We were all ready for the peace and tranquility of the Everglades.

Wally Werderich

Wally Werderich CONDOR awaits its crew during a restaurant stop at Marco Island.

After a 30-minute break we continued along the inside route to Marco Island and boat traffic dwindled as we paddled through Rookery Bay. By 3 p.m. we had reached Marco Island. Wally and I talked Bill into stopping at a restaurant.

An hour later we were back on the water and paddling for the little town of Goodland, the last bit of civilization before we entered the Ten Thousand Islands. Our plan was to paddle through the archipelago and turn east to find an island suitable for camping. As darkness fell we ran into several WaterTribe sailboaters who asked if they could follow us. Wally and Bill looked at the charts and decided that Gullivan Key, about 5 miles away, would be a good choice. Wally and I led the convoy, and when we arrived at Gullivan the tide was out and we could not get close to the beach. We tried White Horse Key 30 minutes farther on and found ourselves in the same situation. Bill, Wally, and I were pretty tired and decided to drag our boats through the 2″ water to get to the beach. We tied the boats up on the beach and quickly set up our tents above the high-tide mark. About 1 a.m. I woke to waves crashing on the beach. I could see our boats in the moonlight; they were still tied up, but I wondered how high the tide would get.

None of us had slept well with the waves so close, but the good news was that we had plenty of water to launch off the beach. Today’s goal was Chokoloskee, the gateway to the Everglades. We cut through the Ten Thousand Islands and at 1:30 p.m. pulled into the ranger station on the north side of Chokoloskee Bay.

It was the hottest day so far, and we quickly headed for the store for some cold drinks, then to the ranger’s office for camping permits. Our first camp was 20 miles away and the next 36 miles after that. The ranger checking us in questioned us our ambitious plans—most paddlers in the Everglades travel no more than 10 miles a day—when another ranger recognized us as WaterTribers and said, “These guys know what they’re doing.”

Chokoloskee Island was 3 miles away. The Havana Café there, known for great Cuban sandwiches, would close at 3 p.m. and it was now about 2. Wally and I went into race mode. The tide was up so we paddled straight across the bay and we arrived in plenty of time. We ordered sandwiches for ourselves and one for Bill. There were a half dozen other WaterTribers on the island, and with strong winds forecast for the next few days, most were ending their trip. I thought we’d be able to make it to Key Largo. We’d camp two nights in the Everglades, arrive in Flamingo on Thursday afternoon, make an early crossing of Florida Bay on Friday, and reach Key Largo that evening.

Wally Werderich

Wally WerderichThere is a reason that the WaterTribe awards a gator tooth to racers who traverse entire Everglades Wilderness Waterway.

Bill, Wally, and I filled all of our water jugs for the Wilderness Waterway trip. I noticed that the tap water had a brownish tint and decided to buy a gallon jug of distilled water in the convenience store. I knew the owner of the store from previous races and asked him about the “brown” water. He said it was fine but that he would call his cousin, the Mayor of Chokoloskee to check on it. It pays to have access to the Choko power structure.

We left Chokoloskee about 5 p.m. and paddled into the Everglades. The Wilderness Waterway was marked by numbered poles and had park service campsites along the route. Shortly after nightfall, about 20 miles from Chokoloskee, we stopped on Possum Key at the camp known as Darwin’s Place. Arthur Leslie Darwin, the “Hermit of Possum Key,” moved here in 1945, built a one-room cinder-block house, raised rabbits, and cultivated bananas on 10 acres of land. He cooked using a gas stove and collected rainwater in a cistern. In 1957 Possum Key became part of the Everglades National Park, but Darwin was allowed to stay. He passed away in 1977 at the age of 112.

Wally Werderich

Wally WerderichA pair of osprey keep watch over the Everglades woods.

The mosquitoes were in full attack mode, so we quickly set up our tents. As I drifted off to sleep with their constant humming outside my tent, I wondered how Darwin survived here.

We were in our boats by 7 a.m. and paddled through miles of bays and connecting rivers with the whole unspoiled area to ourselves. Green mangrove islands were all around us and egrets, herons, ibises, and osprey were everywhere. I noticed the distinctive boils that manatees make in the water. When one erupted near us, splashing CONDOR, Wally let out a squeal. After that we often joked about the “killer” manatees.

Wally Werderich

Wally WerderichSoon after Bill, Rod, and Wally arrived at the Harney River Chickee, darkness fell and the bugs descended upon them.

Just before dark we reached the Harney River chickee, one of several freestanding wooden platforms in the Everglades that provide toilet facilities and tent sites. Bill heated up some water for our freeze-dried meals. We hoped that away from land the bugs would not bother us. But as darkness fell over us so did the no-see-ums, and I abandoned my wish to sleep under the open sky without a tent.

Wally Werderich

Wally WerderichBil Whale, with his mast down and outriggers stowed, leads the way through a passage choked with mangroves.

At daybreak we paddled the Harney River toward Oyster Bay. WaterTribers often struggle getting through narrow waterways here—The Nightmare and Broad Creek—but we hit the creeks at high tide and in the daylight and could pick our way through and around the overgrown foliage. At night and with mosquitoes buzzing, it would have been a lot tougher.

To reach Flamingo we had a lot of open bays to cross. The wind was howling out of the east, and Wally and I paddled hard across each windy and wavy bay, then waited for Bill to catch up before repeating the process. About 2 p.m. we arrived at the canal to Coot Bay. We were about 8 miles from Flamingo. The convenience store there would close at 5:30 p.m. When Bill caught up, we told him we would paddle ahead to get sandwiches and cold drinks. Wally and I again went into race mode. We worked hard paddling across Coot Bay in the wind and 2′ waves. Finally sheltered in Buttonwood Creek, we kept up a good pace over the last 5 miles to Flamingo. We made it to the store a few minutes before 5 p.m. I drank about a quart of cold chocolate milk over the next half hour. Bill came in about 40 minutes behind us, and we had cold drinks and a sandwich waiting for him.

Our plan was to leave Flamingo at about 5 a.m. for the 33-mile crossing of Florida Bay. The wind on the bay was currently out of the east at 15 to 20 knots; Friday’s forecast was for 20 to 25 knots. We needed to leave now. Bill was having some issues with his hands and decided to end his trip at Flamingo.

Shortly after 8 p.m., Wally and I said goodbye to Bill and headed east. We were leaving on a high tide and could cut across the open water and save some time. Much of the first half of Florida Bay is across shallow water, and you must follow the route marked by the occasional marker pole or you’ll run aground. Wally was closely watching his GPS route and giving me constant steering directions. We crossed through the Dump Keys and then made it through the passage that crosses the sandbar known as the Crocodile Dragover. As we entered deeper water, the waves increased to 2 to 3 feet under a forceful wind. Our progress was agonizingly slow. Wally and I had to paddle our hardest just to make 2 miles per hour. Every few hours we would take a brief break in the lee of an island.

About 4 a.m. Wally and I could see the lights of Key Largo, but I desperately needed caffeine to keep me awake. Wally split an energy shot with me and that was enough to make it to daylight. We aimed for the cell-phone tower at the Bay Cove Motel that marks what would have been the finish line for the Everglades Challenge. At 8:30 a.m. two tired paddlers made it to Key Largo. Even though the EC had been canceled and every racer who started would be officially listed as DNF—Did Not Finish— Wally and I did what we set out to do: We finished.![]()

Rod Price is an Orlando-based ultra-distance paddling racer. In 2009 he and partner Ardie Olson won the canoe division of world’s longest canoe race—the Yukon 1000. He is the only racer to have completed North America’s six longest paddling competitions including: the Ultimate Florida Challenge (1200 miles), the Yukon River Quest (444 miles), the Missouri River 340, the Everglades Challenge (300 miles) and the Texas Water Safari (260 miles). At the age of 55, he continues to race. He is the author of Racing to the Yukon and Racing Around Florida, both available on his website.

I have followed the EC for some years and wish to take part in 2016. However, I would be interested to know how the US Coast Guard could mandate that all WaterTribe competitors leave the water while not doing so to any other boaters on the water. Apparently a day sailor asked over the radio whether they should go ashore. When they said they were not part of the WaterTribe they were told that they did not need to go ashore. Seems odd to me.

Does anyone know what sail Bill Whale is using?

The sail and outrigger are made by Balogh Sail Designs.

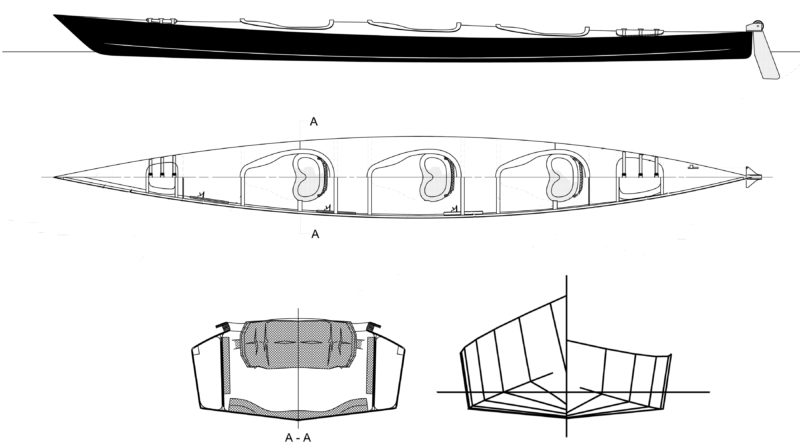

Can someone tell me the make of sail on CONDOR?

CONDOR carries a downwind sail made by Spirit Sails. The flexible fiberglass masts are attached to a V-shaped fitting that can be set at different angles in a deck-mounted socket.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor, Small Boats Monthly