Ben Fuller

Ben FullerTo facilitate reading in magnetic bearings, this Nav-Aid has been marked with a line through the angle of the magnetic deviation for the area covered by the chart.

I like “big-screen” navigation, and in a small boat the only way I can do it is to use an old-fashioned paper chart. My handheld GPS often sits idle. While it’s great for detail, it’s hard to read in sun and needs seconds, even minutes to give me big-picture information. The challenge for chart users on little boats is determining one’s position or calculating course and distance to a spot, a “waypoint” in today’s language. The usual navigational aids—parallel rulers and large rigid-armed protractors—need a big flat place, out of the wind and spray. They don’t work on kayak decks, rowboat thwarts, or cockpit seats.

Chuck Sutherland, a serious paddler and scientist, solved the problem decades ago with his Small Craft Nav-Aid. It’s a compass rose printed on transparent plastic, with a monofilament line coming out of the center. Designed to be used on a kayak deck or an open-boat thwart, it provides results in a fraction of the time needed for conventional tools.

Using the Nav-Aid is simple. You place the center of the rose over a point of interest and align the edges of the plastic with the latitude or longitude lines on the chart. Stretch the line out to a second point and read the bearing off the rose. To get distance, mark the monofilament with miles according to the scale of your chart using a waterproof marker, and the line becomes a movable scale. When the Nav-Aid is aligned with the chart, its compass rose will read true north and you can calculate magnetic north by doing the math for the local variation or customize the Nav-Aid to read magnetic. With a waterproof marker, draw a line on the rose through the variation, and add two lines at 90 degrees, kind of like a sideways H. Orient these lines to the chart’s longitude and latitude, and the compass rose reads magnetic. (If you travel to another region with a different variation, draw new lines in a different color.)

Now you can read the magnetic bearing and distance from your position to any point on the chart in less time than it takes me to write this, much faster than using a GPS. I’ve customized my Nav-Aid a bit further by marking its lanyard with the scale of nautical miles; it’s really handy when trying to figure out non straight-line distances. You can also mark a scale on the side of the plastic.

The Nav-Aid comes with a booklet of instructions and a mini-course in chart use. There are some issues to be aware of. With the prevalence of non-NOAA charts, the scale on the chart may be different from the 1:40,000 system common to NOAA. You may need to put an additional set of markings on your monofilament in a different color or estimate the differences. I also make paper copies of the scales and put them in my chart case at a convenient place on the chart.

Ben Fuller

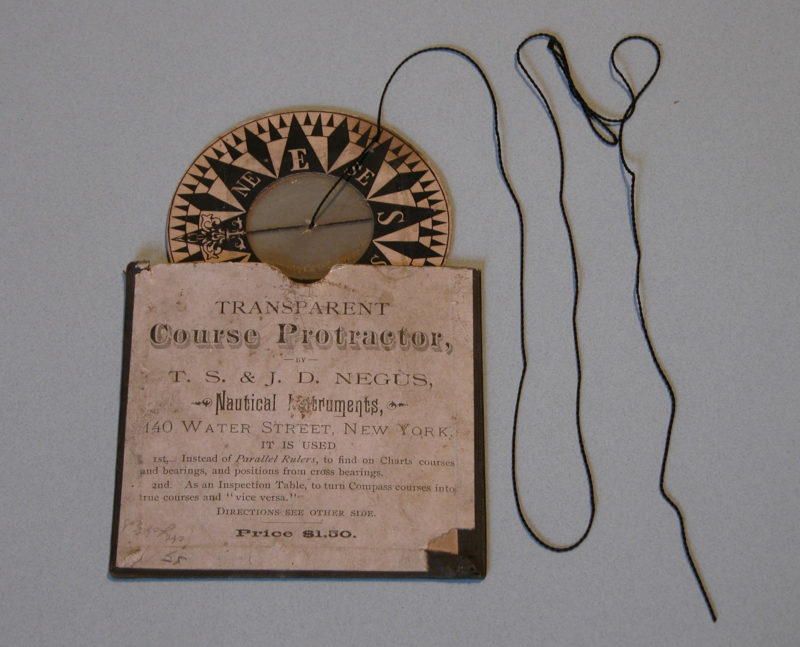

Ben FullerThis 19th-century device is quite similar to the Nav-Aid in appearance and function.

More than a century ago, the T.S. & J.D. Negus nautical instrument company of New York City patented a similar protractor-type instrument made of isinglass, using a silk thread for a string. The one shown here, printed on a round card, is in the collection of the Penobscot Maritime Museum. A Negus Course Protractor in the collection of the Mystic Seaport Maritime museum is printed on a square card. The protractor is included in the Negus catalog of 1899 but it didn’t sell well, because ship captains didn’t need it. They had chart tables, parallel rulers, and armed protractors. When Chuck developed the Nav-Aid for kayaks and small boats, he didn’t know about the Negus protractor, and mini-GPS devices didn’t exist. Things have changed electronically, but I still use and like my Nav-Aid. You will too.![]()

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, has been messing about in small boats for a very long time. He is owned by a dozen or more boats ranging from an International Canoe to a faering.

The Nav-Aid is available by mailing $8 to Chuck Sutherland at 2210 Finland Road, Green Lane, PA 18054. You can reach Chuck by email at [email protected].

Is there a product that might be useful for boatbuilding, cruising or shore-side camping that you’d like us to review? Please email your suggestions.

If you plan to mark distances on your monofilament line, be sure to use the scale on the right or left sides of the chart, as they show true nautical miles and fractions thereof. The scales at the top and bottom will throw off your calculations because the longitudinal lines converge as they approach the poles. Of course, you can also use the scale in the chart’s legend, but that is a part that I often trim away, as I try to make the charts as compact as possible to go into my waterproof chart case for using on the deck of my kayak.

I’m in Bellingham, WA, and much of my paddling is done in Canadian waters for which we use Canadian Hydrographic charts. These come in many different scales, and as far as I know, there is no “standard” scale

for Canadian charts. This matters, because I believe errors often occur because the navigator isn’t aware of the scale of his chart. I read of one case where a power-boating family from out of state left Anacortes, WA to head for the San Juan Islands. They ended up in Victoria, BC because they expected the San Juans to be much larger islands than they actually are. The tone of the article about them seemed to indicate they were more amused than embarrassed by their blunder.

Basically, this is a Douglas Protractor with a line from the center, is it not? It’s a handy gadget for the job, I should think. Not that I use my Douglas Protractor much these days, but I’ll give serious thought to drilling a hole in its center and installing a length of monofilament.

Not so sure about marking the lanyard with nautical miles. This will only work when using same-scale charts; okay if you’re mostly boating in the one area and likewise probably only using one chart, but could be a problem if you have to shift to another chart on a different scale.

The point David Peebles made in his comment about using the side of the chart to take distances off is a good one. I thought everyone knew this, but frequently strike boaties who use the bottom edge and in consequence have erroneous ideas about distances.

The Douglas protractor is one of a handful of similar devices I’ve found on the web; it’s usually square and without a cord at the center. Another common device is a military protractor in a semi-circle with a string at the center and a perimeter marked not in degrees but in mils (6400 mils in a full circle).

Christopher Cunningham, Editor

Most of the devices on the market are larger than the Nav-Aid and have more bells and whistles. I know about the scale problem as I’m using waterproof charts as much as the NOAA 1:40,000 series. One way around it is to mark some scales on the edges of the NAV-AID. After a bunch of years I broke my Nav-Aid that had more scales edge marked on it. You can also mark the string that you use as a lanyard with a different scale. If you do that, measure your distance with the monofilament then put it next to the other appropriate scale.

I usually use charts from Waterproof Charts, Inc. Their scales are a little closer to standard NOAA. You also need to adjust for the NOAA chart books.