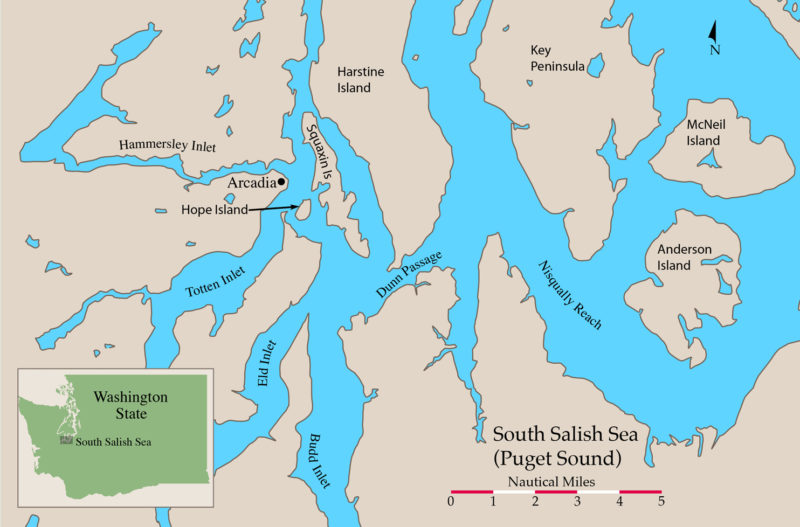

The boat ramp in Arcadia, Washington, lies at the end of a quiet road where a handful of modest houses nestle among cedar, fir, and alder trees. I stood on the ramp’s sloping cement with my 15-year-old son, Merry, looking out at this southern edge of the Salish Sea. To the east lay Hope and Squaxin, two tree-clad islands scarcely more than a half mile from the Arcadia shore, with the snow-topped peak of Mount Rainier hovering above them in the distance.

all photographs by the author

all photographs by the authorAs Andy approached Anderson Island, Mt Rainier seemed to float above the clouds. This section of the Salish Sea is lightly settled and less traveled than areas closer to Seattle.

We had left our Portland, Oregon, home the day before, driving 100 miles north to this hamlet, the launch point for a three-day camp-cruising expedition with our friends Andy and Tim. Our plan was to explore Hope, Squaxin, and Anderson islands, camping at sites along the Cascadia Marine Trail, a network of access points for non-motorized small craft. I’ve sailed and paddled this region many times, yet I’ve seen only a fraction of its many nooks and crannies, so each trip is a chance to see something new.

Merry and I were first at the ramp with ROW BIRD, our 18′ Iain Oughtred Arctic Tern. Soon after, Andy arrived with his 17′ Antonio Dias–designed Harrier, WILBUR LARCH, but by one o’clock, Tim had still not appeared. Figuring that he’d catch up with us at our campsite, Andy, Merry, and I loaded the boats and launched. We were bound for nearby Hope Island State Park, but we began with a side trip into Totten Inlet, which transitions along its winding 9-mile length from a shore crowded with homes to a quiet, muddy backwater. I was pleased when Andy invited Merry aboard WILBUR LARCH. My son would get the opportunity to take the helm of a new boat and to learn the finer points of sailing from someone other than his dad.

Andy, a parent himself, was a good mentor to Merry, listening more than he talked and offering tips rather than lectures. Merry found the Harrier to be faster, more responsive, and tippier than the Arctic Tern he was used to.

When we started out from Arcadia, the wind was a relaxing wisp, barely requiring a hand on the tiller, but over the next hour it rose, and ROW BIRD’s speed increased from quick to heart-pumping. Bouncing through chop, pushed on by a few big puffs, I tightened my grip on the mainsheet. It was satisfying to watch the concentration on Merry’s face as he adjusted WILBUR LARCH’s course and sail trim to accommodate the changing conditions.

As the sun started getting low in the sky, we headed for our campsite. The many headlands and inlets here disperse breezes, contributing to the area’s reputation for fluky conditions and extended periods of calm. Aware that the breeze might die at any moment, I savored a few long tacks before heading in. Andy and Merry rowed directly for shore though, and when I finally arrived at the island, they were already setting an anchor for the night.

We lugged our gear into the dense evergreen woods, where we found the campground deserted. There were picnic tables at the campsites, but when we returned to the beach, the view of the clouds, now glowing pink with the setting sun, was so striking that we decided to cook dinner right there. Just as we were savoring our last bites, a sailing dinghy came zipping near the shore. Merry was the first to recognize its sole occupant: “It’s Tim!”

Tim dropped sail as he drove his 13′ Sparkman & Stephens Blue Jay up to the beach and stepped confidently ashore in street shoes. The rest of us, in our knee-high rubber boots, were impressed by his insouciance. I wondered how Tim’s lightly built racing vessel would fare as we got into more exposed waters, tidal currents, and areas of heavier air.

Hope Island State Park’s primitive campground and lack of dock make it a quiet stopover for small, beachable boats.

The next morning Andy and I stood on the shore, mesmerized by the reflection of the dawn sky in the dark blue waters between Squaxin and Hope islands. For a dream-like moment it seemed as though the sea and sky were one; that speaking a single word might make the whole scene disintegrate. And where was my teenager during this ethereal moment? Asleep in his tent, lost to the magical world around him.

The offer of a hot breakfast got Merry out of his sleeping bag, and yet sleep still clung to his eyes 45 minutes later, when we were all finally loaded and ready to go. The water was smooth and glassy as we pulled away from the shore; it looked like it was going to be a slow, 10-mile row to Anderson Island, our destination for the night. I watched Merry relax in the stern, then sit up, his attention attracted by a seal that was following us. It was clear to me that, despite his reluctance to rise this morning, my son was happy to be here on the water with me.

You can’t make someone else love boating, even if you really want to, and I’ve been careful not to force it upon my boys. Years ago, many an afternoon on the water was cut short when our sailboat heeled over, alarming a then much younger Merry, who would scream, “We’re going to die!” What I considered fun knot-tying exercises at home were greeted with groans of boredom from him and his brother. But while my younger son has never cared much for the water, Merry gradually lost his fear of boats and developed a spark of interest, one I’ve tended carefully.

We do most of our boating close to home, on the Willamette and Columbia rivers; but over the years, I talked up the allure of saltwater sailing, imbuing it with a sense of mystery and magic, describing to Merry the fascinating creatures, challenging conditions, and delicious food I encountered on my trips. Eventually, it worked, and three years ago, he decided to join me and some friends on an annual pilgrimage to the Salish Sea, which spans the inland waterways of Washington State and British Columbia. Each spring since then, Merry and I have found ourselves a quiet place to sail, row, and camp. We enjoy each other’s company on these expeditions, and I always hope he’ll learn something too. Still, I try not to be didactic. The experience of cruising—traveling with other boats, sorting out tides and weather, and outfitting the boat—is enough to impart the lessons of sea lore and to foster what I hope will be a lifelong love of boats.

At home, Merry’s no fan of cooking, but in camp and near the water, he’s happy to oblige. Isobutane canister stoves nicely balance convenience and safety on shorter trips.

As I rowed, I scanned the water ahead for signs of currents. One crossed our course, and pulled us toward a mooring buoy. Merry watched the current swirl around it, a sure sign that, despite the seemingly still conditions, a lot of water was on the move.

The wind was so variable that we found ourselves frequently switching between sailing and rowing. Although we weren’t racing, Merry and I watched our companions’ choice of sail or oars closely.

During a lull in the wind, Merry and I skimmed along under oars in the clear, still waters near shore, looking for marine life. We spotted moon snails as big as grapefruit, golden sea stars, and plumose anemones with their feathery tentacles. Our best sighting was a hefty maroon rock crab scuttling through clumps of seaweed. Its stout claws looked large enough to make a tasty meal. Merry has always loved looking for wildlife, and even at the age of 15 he maintains the endearing belief that he’ll be able to snag dinner with a long stick. As in past years, he tried and failed to even touch the crab, let alone capture it, but that didn’t diminish the fun of the hunt for either of us.

Untethered from his smart phone, Merry became increasingly absorbed by the natural world all around, especially by a large crab he hoped to snare for dinner.

The weather radio had forecast 5 to 10 knots of wind from the north, but the warm air was mostly still. In his light, simple boat and with his experience racing his sailing skiff, Tim was our pacesetter. Andy’s boat was lighter and sleeker than ours, and he frequently took the middle position. Despite the weak winds, conversation on our boat was cheerful. With 4 miles to go until we reached Anderson Island and a good six hours of daylight remaining, there was no reason to rush. Merry and I set out nuts, fruit, and sandwich fixings on the side benches and prepared to nosh. “This,” I said, basking in the sun, “is what a cruise is all about.”

As we ghosted along I persuaded Tim to come aboard ROW BIRD to fix a persistent crease in my balanced lug mainsail. Merry boarded the Blue Jay. While I leaned lazily against the mizzenmast, Tim lay on the foredeck, adjusting the downhaul, outhaul, and lashings on the tack. Tinkering is what he likes best about sailing.

Merry, at the Blue Jay’s helm, beamed like a teen given the keys to a new car. Oblivious to the peeling paint and the water sloshing beneath the floorboards, he kept a grip on the tiller and tugged on the mainsheet, excited to chart his own course. Tim and I kept an eye on him, occasionally offering sailing advice, and contentedly cruised along, if slowly, toward our destination. Halfway to Anderson Island, the wind ceased, and brought an end to our sail tuning. We’d need a more serious breeze to determine whether Tim’s doctoring had made a difference.

I’d installed an extra oarlock on the aft, port side of ROW BIRD to use with an oar for a makeshift rudder or to use for sculling. I’d never been able to scull effectively, so I asked Tim to demonstrate.

Even with an extra boat in tow, Tim’s sculling produced enough power to move us steadily along. He taught me that the oar must dig deep into the water to be effective.

He set an oar in the oarlock, and began making a graceful swaying, figure-eight motion. ROW BIRD slipped forward at about a knot and a half, and we left Merry behind. He was in no danger, but I felt a slight pang at watching my son recede into the distance. So we looped back; I grabbed the Blue Jay’s painter and took Merry in tow as Tim sculled. All was well until the blade of the oar broke off at the throat.

We were a mile from shore, with no wind. We could scull with the other oar to Anderson Island, but I worried about making tomorrow’s 10-mile trip back to the launch ramp with a single oar. Smiling, Tim hopped into his boat and pulled out a pair of clunky 9′ oars. He handed them to me and took back his painter. They were heavy ash workboat oars, but I was glad to have them.

“But how will you get to shore?” I asked.

Tim laughed and pulled out a paddle. Sitting atop the rail, he began to propel the boat forward while Merry handled the sail and rudder. My son grinned, clearly soaking up Tim’s make-do attitude and paddling skills. The Blue Jay was now moving through the water almost as swiftly as I was able to row ROW BIRD.

A canoe paddle can make an effective and easily stowed auxiliary means of locomotion, especially for a boat as light as a Blue Jay.

An hour later, we reached the shallow cove at the nature preserve where we intended to camp. Andy had arrived before us and was relaxing at anchor aboard WILBUR LARCH, a book in hand. Surprised that he hadn’t pulled ashore yet, we soon realized that he was waiting for the flood tide to rise enough to allow us to set our boats above a line of barnacle-covered cobbles.

Ashore at Anderson Island, the crew enjoyed basking on the smooth round stones that had soaked up the sun’s warmth.

Merry and I looked for a clear patch of sand in which to drop our anchor, and we noticed that the bottom had a lumpy, purplish covering. Rowing into shallower water, we were amazed to discover that the odd-looking mass was composed of thousands of sand dollars. We had seen their bleached skeletons before, but were never lucky enough to see them alive with their velvety covering of tiny lavender spines.

We set our anchors and ran stern lines to the land so the boats would stay perpendicular to the shore, facing into any waves that might arrive. We checked the tide tables and positioned the boats so that they could be on the hard during the evening’s low tide, but would float again with the morning high tide.

After setting up camp, I drew in my sketchbook, Merry scavenged for kindling and prepared a bonfire, and Tim and Andy went for hike.

When we reconvened at our campsite late in the day, a rich, musty smell blew off the salt marsh behind us; stands of rusty red madrone and ancient Douglas-fir loomed over the hillside beyond. We sat by the fire, talking well into the night.

Mild temperatures and a scarcity of insects make this part of the Salish Sea ideal for camping. A canvas painter’s dropcloth made a simple, but effective cockpit tent for Tim’s boat.

We woke the next morning to clear skies and still air. After breakfast, we broke camp and packed the boats. Our best bet for a speedy return to Arcadia was to use eddies and tidal currents, search for pockets of breeze, and row—a lot. All morning, Merry and I traded off the oars and watched harbor porpoises and seals come and go. We talked about tide charts and how to read them, life at home, and the Maine peapod Merry was planning to buy. There was none of the teenage arguing and eye-rolling I’d become accustomed to at home. On the water, we simply enjoyed hanging out.

With about a mile to go, Merry noticed a patch of water darken some distance astern of us. He let the oars sit still in the oarlocks and watched the textured pattern, aware that it would bring an end to rowing. As it drew near, he enthusiastically grabbed the tiller while I hoisted the mainsail. A minute or two passed and then our sail bellied out and we were soon coasting along Hope Island, relishing the lightness and speed of the boat’s motion without our labor at the oars. Sunlight glinted off the water. The Salish Sea was empty of any craft but ours. We were homeward bound, but in a few weeks Merry would be launching his peapod. Next year, I was confident there would be one more sail in our fleet.![]()

Bruce Bateau sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at his web site, Terrapin Tales.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Wonderful article! Our family has sailed, rowed, and motored the South Sound many times. We had a cabin on Hammersley Inlet and did our sightseeing exactly in the region of this trip. Very well done. It sure brought back many memories.

I love the Salish Sea, and am lucky enough to live close to Bellingham Bay. I, too, have sailed the Squaxin-Anderson islands loop, but in a much larger boat. There are two trips I would recommend to others. The Arctic Tern, the Harrrier and Merry’s new peapod could easily make the run from Sandy Point, near Bellingham, to Matia and Sucia Islands in the San Juans. It is a row/sail across fairly open water, with tankers sometimes requiring maneuvers, but it is worth the effort. There is an inner trip, from the boat launch at Larrabee State Park, some 6 miles to Saddlebag Island. There are campgrounds at Matia, Sucia, and Saddlebag, though the one at Saddlebag is sadly ignored and sometimes dirty. They’re all fun trips, however. Know your tides and tide rip patterns before going. The rip off Sandy Point is no joke on certain tidal changes. It was nice to read the article.

Sucia is definitely on my list for this summer. I sometimes worry Merry’s peapod, PORPOISE, won’t handle rough conditions in a large crossing, so I came up with the idea of hauling Merry aboard and towing PORPOISE. My initial trials with ROW BIRD have shown that the peapod tracks quite nicely. I can see a new adventure ahead of us. Ironically, an earlier adventure I’d written up was about us cruising to Saddlebag Island. We had it all to ourselves for two nights, at a cost of just $24!

Great article! I live on Eld Inlet adjacent to the Steamboat Peninsula, just south of Hope Island, and sail these waters frequently during the summer months. I really enjoyed reading about your trip; it makes me miss my previous boat, a Devlin Nancy’s China.

Bruce,

Wonderful article! I really enjoyed the read and hope you will continue writing! Thanks for taking the time last October to show me RowBird when I was in Portland. I enjoyed our visit and your advice on improvements to your Arctic Tern. One day I will return to the Pacific Northwest in my Sooty Tern (once it is done) and seek your sailing advice!

A nice story, Bruce, and the photos were great. Although I’m 83 now and too infirm to sail, I’ve sailed these waters for years and have never tired of them. There’s always something new to see or experience. You were indeed lucky to view a porpoise. I’ve never seen one in these waters. It’s interesting that you didn’t mention Dana Passage, through which the tide can run like a river. Did you plan to go through there on the ebb outbound and the flood inbound or did it just happen to work out that way?

Bruce, this is a lovely story. I live in Bellingham and row all around the San Juans and Gulf Islands. Your ability to evoke quietness and natural habitat is a palliative to land’s demands. For a trip to Sucia and Matia in the San Juans, I’d suggest launching at Gooseberry Point on an early morning flood, which will scoot you around the top of Lummi Island toward North Beach on Orcas. Makie sure there’s little wind or, if wind, a southerly. Time the currents so you cross Parker Reef at the top of the flood. It won’t take long to reach either Sucia or Matia. I tend to like Matia better than Sucia, particularly during the warmer months as Sucia can get crowded. I generally return from Matia in the evening after the winds settle down. One has to be savvy about Point Migley—the north tip of Lummi Island—when the tide turns, particularly against a southerly. It can be unpleasant at minimum. If a northwesterly picks up, batten down. It has the whole Strait of Georgia to puff itself up and Hale Passage can get, well, even nastier than Point Migley. You’ve got a new reader at “Terrapin Tales.” Many thanks.