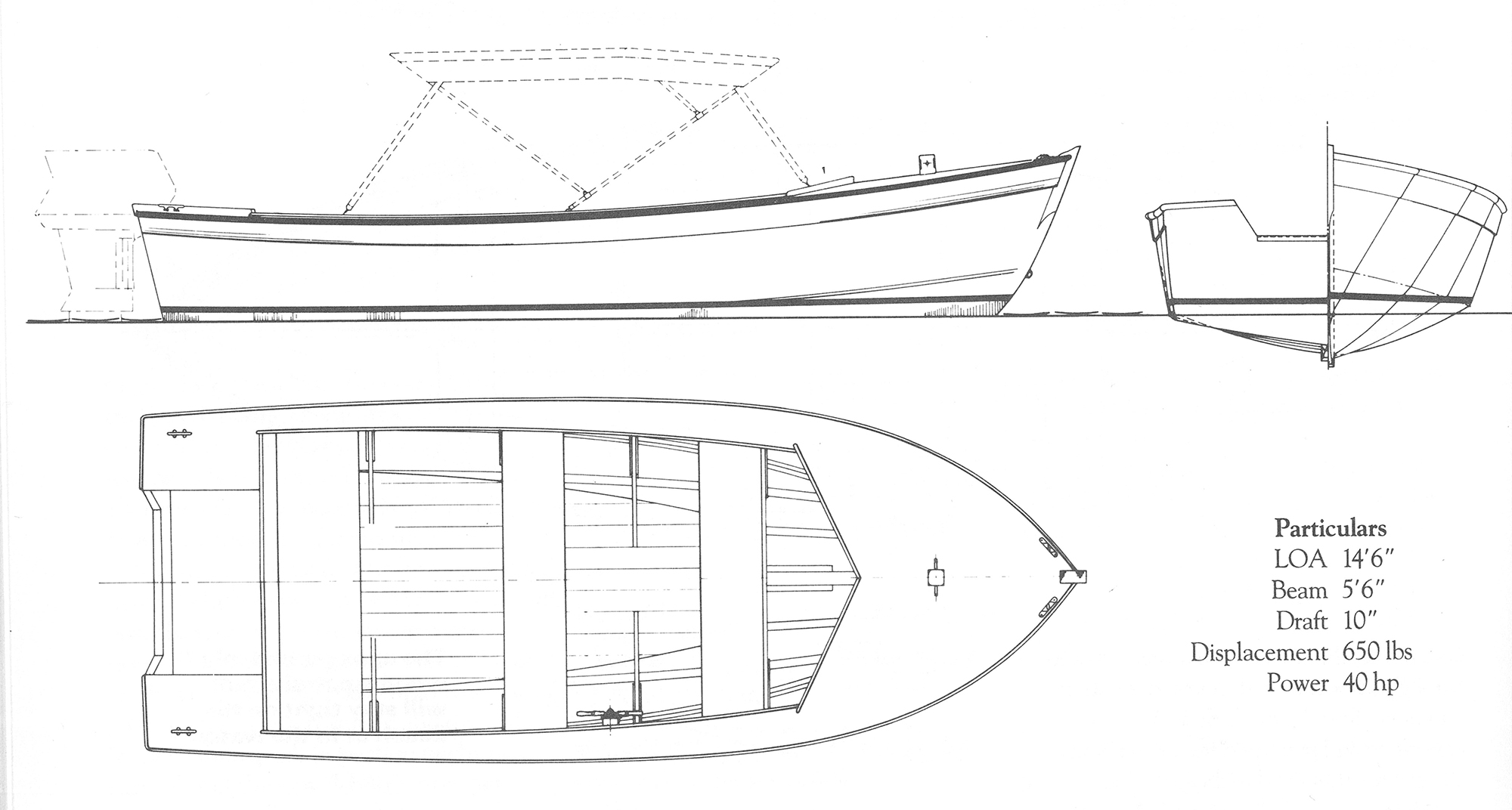

Little Moby

If we build monuments to ourselves, the late Charlie Wittholz constructed a memorial with highly crafted plans that describe wholesome boats. Little Moby came near the end of the designer’s 50-year career, and he held the husky plywood skiff in high regard.

Wittholz referred to Moby as a “rough, water skiff.” The appellation seems appropriate when we look at her ample freeboard, moderate deadrise, and robust construction. The freeboard will help keep her dry and provide some reserve stability. Despite her high sides, windage shouldn’t be a problem here as the worst offenders – windshields, houses, masts, and standing rigging – are absent. (The sketched-in Bimini top would be stowed in a hard chance.) As may be, the hull’s good grip on the water, and 40 horses strapped to the transom, ought to provide peace of mind in tight situations.

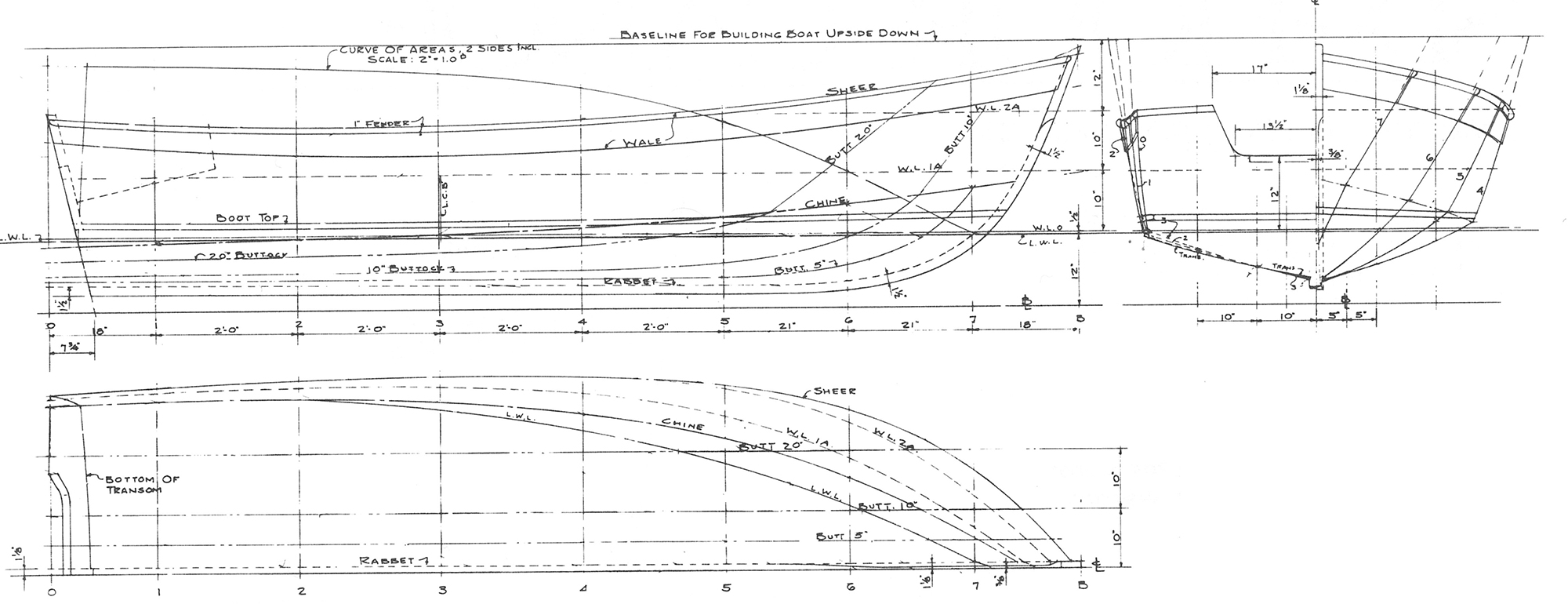

Deadrise ( cross-sectional V-shape to the bottom) will ease Moby’s motion in wave action – at the cost of some initial static stability. That is to say, a simple flat-bottomed skiff of similar proportions would tend to be steadier on its feet when at rest in a slick calm. Also, if both boats were to have equally straight runs, the flat, bottomed design might require less power to achieve and maintain planing. Speed in rough water is another matter.

Had Wittholz chosen to enter additional deadrise in the design equation, Moby might blast to windward more smoothly; but she’d not make a solid plat, form for fishing or other low-velocity activities. With 13° deadrise at the transom (measured upward from horizontal to the boat’s bottom) and 15 ½° at Station 3, this skiff displays considerably less than the approximately 24° deadrise usually associated with high-speed, “deep-V” boats of the Moppie type.

While we’re talking about the hull lines, notice the convex sections in the forward bottom. These curves develop automatically as the plywood sheets are bent into a conical shape. (In this case, the projected apex of the cone probably would fall on the baseline almost directly below the stemhead.) If a builder tries to force the plywood sheets hard against dead-straight frames in this area, the builder will lose. Copiously shimmed frames, sometimes seen in bluff-bowed boats of this construction, provide mute testimony to past battles.

Deadrise will ease motion in waves -at the cost of some initial stability.

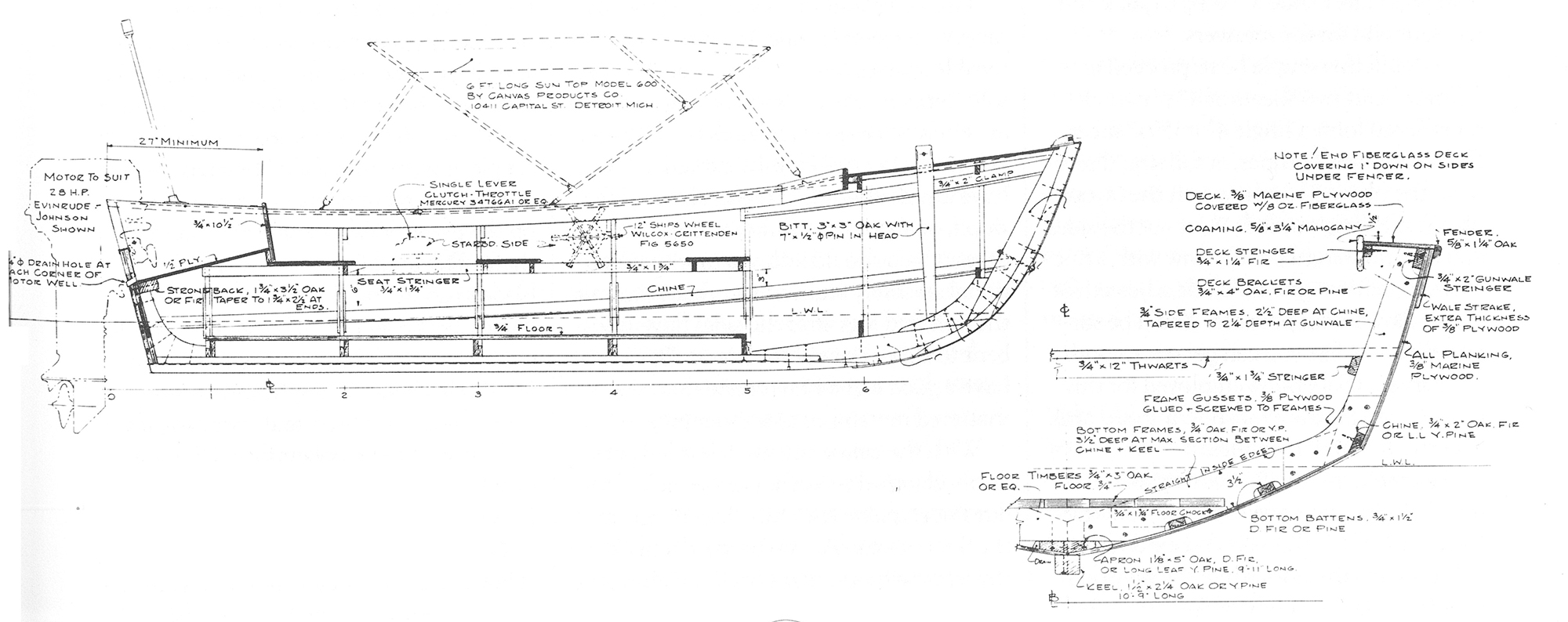

Moby’s fully framed, ¾” plywood hull has rigidity to spare. Much of the internal structure could be eliminated if we were to attempt a conversion to stitch-and-tape construction (see WoodenBoat No. 106, page 80). The relative merits of these building methods can make for spirited debate. It would seem that the latter technique sometimes trades a cleaner boat for a dirtier shop. It would seem, too, that a composite (“taped”) chine can produce a stronger joint than can any solid chine log of reasonable proportions. There seems little question that a stitch-and-tape boat goes together very fast – at least until we have to grind and sand…. And so the arguments go. The bottom line: When properly accomplished, both methods can provide more than sufficient strength.

Less than a year ago, Wittholz wrote to us saying that “the world seems to be turning to stitch-and-glue construction.” His letter indicated neither approval nor disapproval. Whether he, too, would have dispensed with chine logs in favor of epoxy fillets was left unsaid. We should have asked.

We might simplify Moby’s internal structure, but she’s light and rigid just as drawn.

Moby’s layout speaks of tradition -three thwarts and a side-mounted steering wheel. This wheel orientation, though fine for slow launches, might supply cause for concern here. The arrangement doesn’t lend itself to hand-over-hand wheel spinning, sometimes desirable for tight maneuvering and in emergency situations. Perhaps a small console hung from Frame 4 would permit the more familiar athwartships mounting without stealing too much space. In any case, if you should see this writer tooling around the cove at 25 knots while clutching the king spoke of a side-mounted Wilcox Crittenden wheel, be afraid.

From Moby’s crisply sculpted stemhead and mooring bitt, past the coaming, to the afterdeck and splash well, Wittholz made a fine job of combining traditional appearance with contemporary performance. This honest skiff deserves a good measure of popularity.

-M.O’B

Plans from The WoodenBoat Store, Naskeag Rd., Brooklin, ME 04616.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.