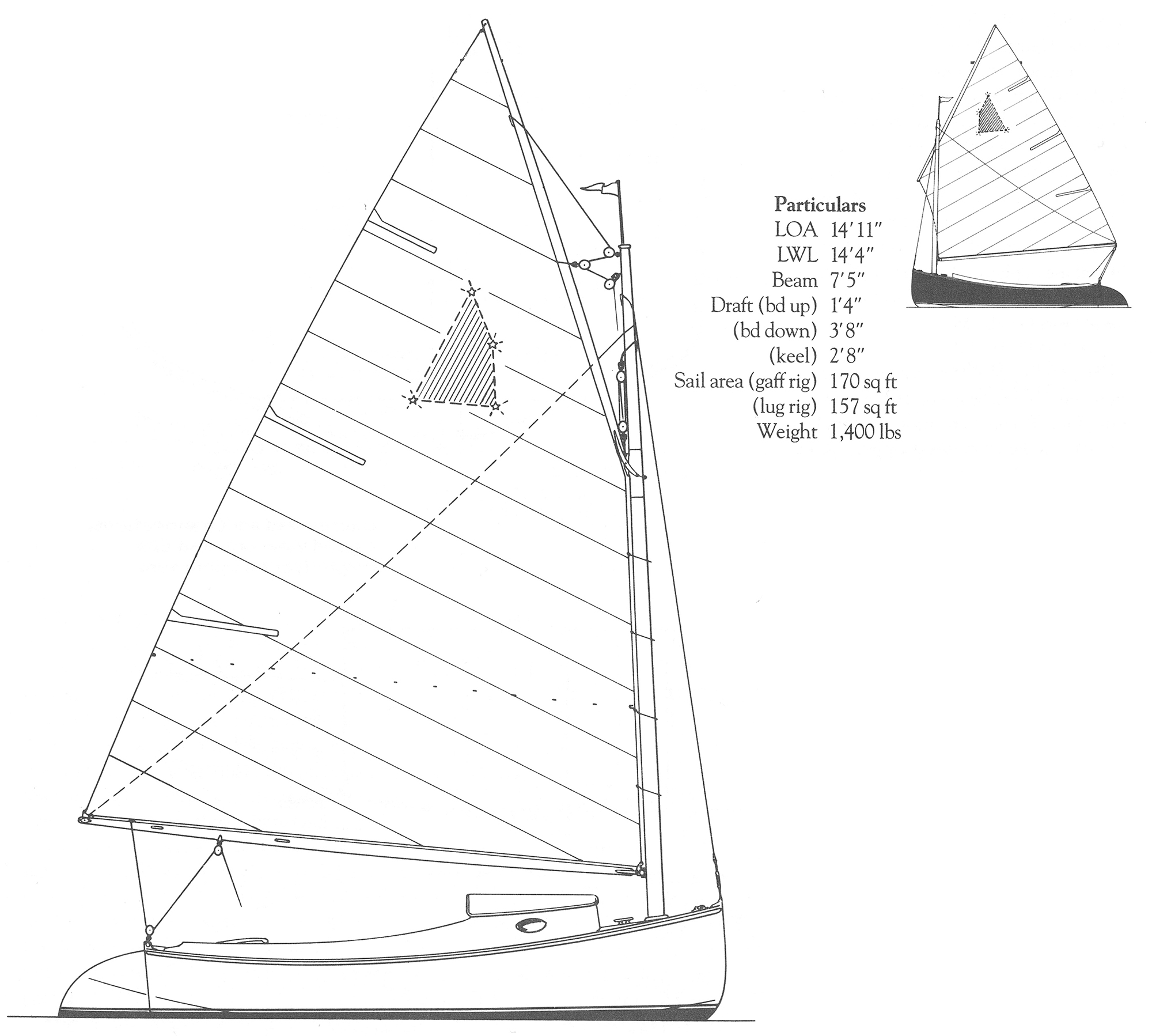

Corvus comes with a gaff-headed sail and a cuddy, or as an open, lug-rugged daysailer (far right).

A small boat with a big heart,” that’s how an anonymous editor at WoodenBoat described this little catboat from Charlie Wittholz’s drawing table.

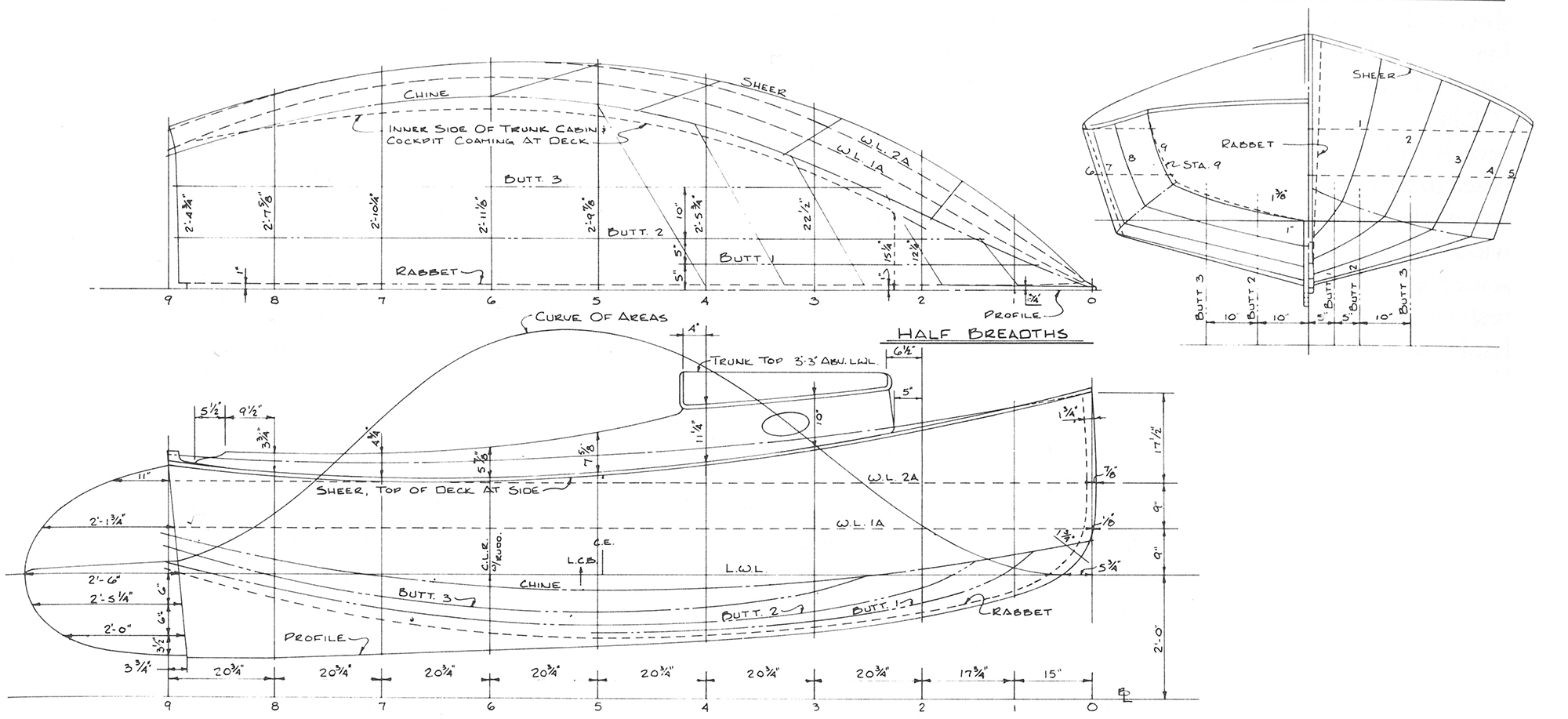

In fact, Corvus (named for a stellar constellation that resembles a gaff-headed sail) might be just about the right size for a cat-boat. Measuring 14’11” by 7’5″ on deck, she’s big enough to provide the traditional catboat benefits, yet small enough to mitigate traditional catboat deficiencies.

As soon as we hoist sail, Corvus will want to take off – whether we’re ready or not. Unlike more sophisticated (and complex) rigs that can leave their foresails or headsails in the bag and lie to their after, most sails, catboats don’t make good weathervanes. But, unlike her larger single-sail cousins, this boat will be amenable to casual control. Grabbing hold of a luffing 170-sq-ft sail bears little resemblance to trying to tame the 500 sq ft of flailing Dacron we might find on a 25′ cat.

Once underway, Corvus will tug at the skipper’s arm with the usual catboat weather helm. We can’t easily avoid strong weather helm when designing a catboat. The long boom causes the sail’s real center of effort to move well outboard when reaching and running, which creates a healthy turning moment. (The calculated center of effort represents the geometrical center for the sail as drawn on a flat, two-dimensional piece of paper. It’s helpful for purposes of design and comparison, but it doesn’t represent the effective center of force.)

The short, fat hull only makes matters worse. As the boat heels down, its water-lines become wildly asymmetrical – strongly convex on the lee side and straighter on the weather bottom. This configuration will want to turn the cat-boat, any boat, towards its high side. Hard chines and full bows associated with sheet-plywood construction reinforce this phenomenon. Again, Corvus is saved by her small size (and by the relatively far aft location of her centerboard). Her weather helm seems little more than a polite reminder of trim.

The Corvus hull: lots of shape for sheet plywood.

An advertisement for the fiberglass Marshall 18′ catboat made the rounds of the yachting press a decade ago. Referring to the simplicity of the boat’s propulsion system, a copywriter stressed the joy of having “only one string [sheet] to pull.” Indeed, relatively small catboats are easy to sail. They are not necessarily easy to sail well. Without headsails to direct airflow, the set and trim of the catboat’s single sail become critically important and, often, more difficult to accomplish perfectly. Novice sailors seem inclined to sail around for hours on end with everything strapped down hard – no matter what the apparent wind direction.

As may be, Corvus is a gentle boat, and she will reward proper handling. If you’ve not worked with a gaff-headed sail before, you might find the experience to be a revelation. When hoisting sail, set up the throat (lower) halyard hard, and haul sufficient tension into the peak halyard to form vertical wrinkles running parallel to a line from the sail’s head to tack when it is luffing. How many wrinkles, and how deep should they be? That will depend upon the cut of the sail, the angle of the gaff, the strength of the wind, the point of sail, and your mood. In due course, experience will let you know what’s right. I’ll note in passing that most beginners seem to carry too little tension in the peak halyard.

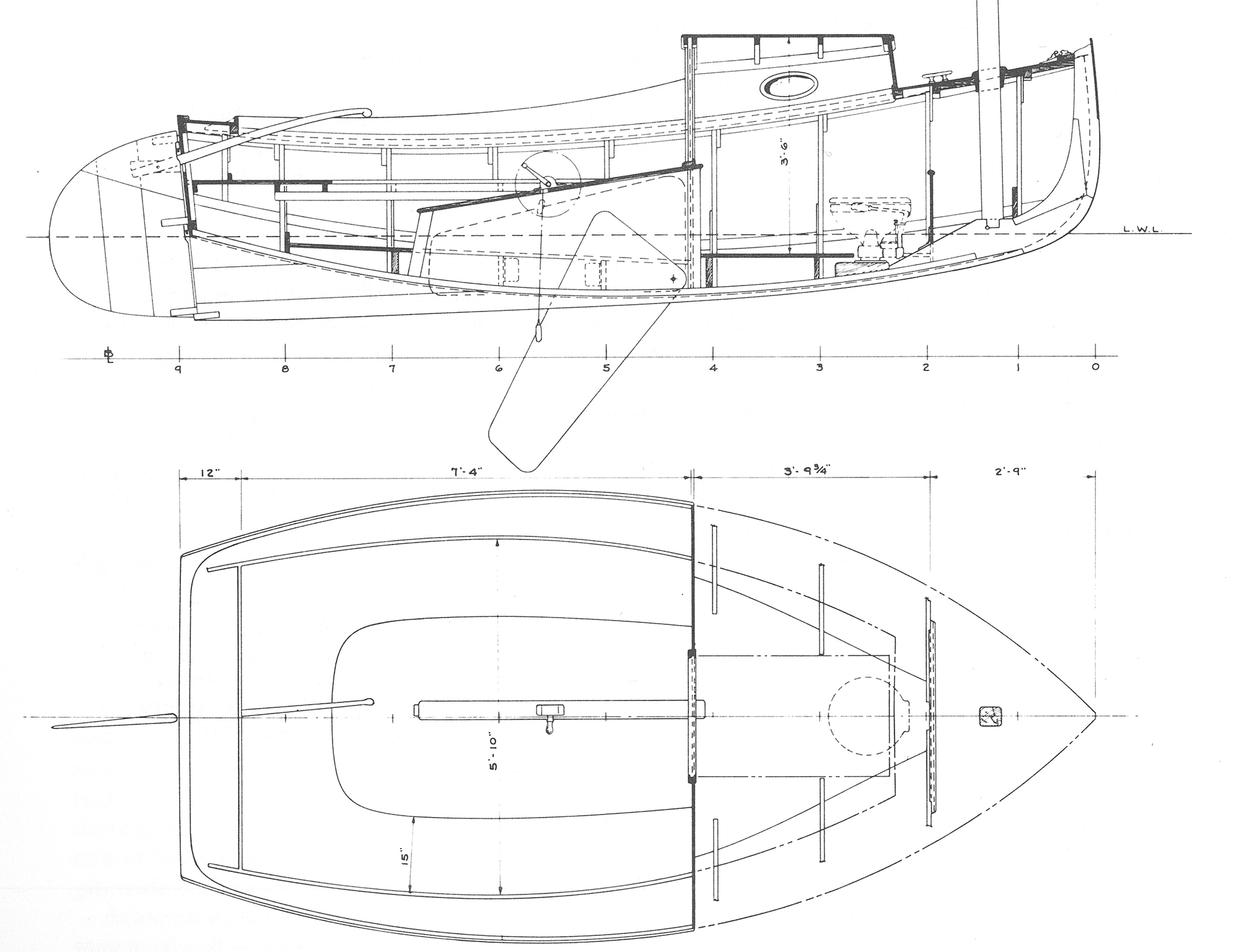

In order to grab the attention of Madison Avenue’s “average family,” a production builder might be tempted to erect a split-level house on Corvus’s deck. For the way most of us will sail her, the cuddy and large cockpit shown here make more sense. The 3’6″ headroom described on the plans seems to be about the comfortable minimum for using an enclosed head. Of course, we’ll replace the traditional marine unit depicted in the drawings with one of the portable variety. We’ll sleep in the cockpit – dozing off on the benches while under sail, and secure beneath a boom tent for the night.

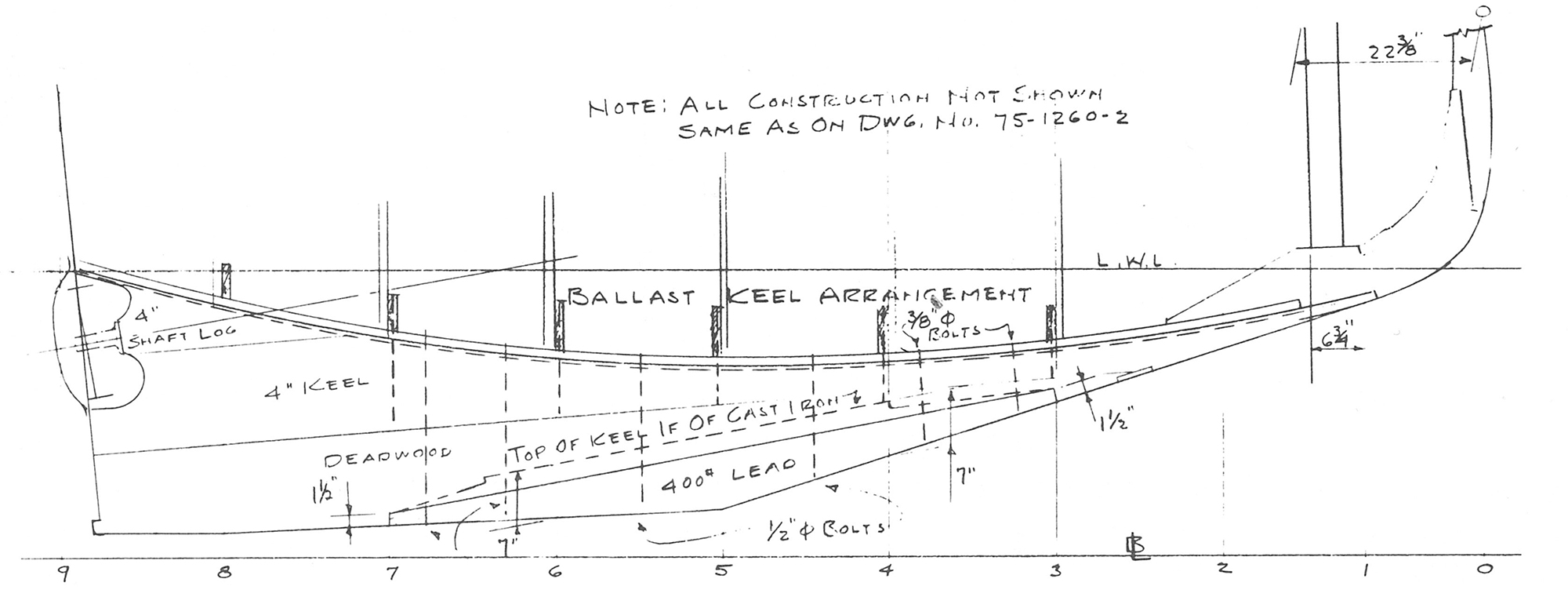

Not many 14’11” sailboats can justify an optional inboard auxiliary. Corvus can.

We’ll cook our meals and warm the coffee on a small gimbaled stove mounted on the after face of the main bulkhead. Most of the time, the stove will hang from an extra mounting plate fixed to the bulkhead below decks. We’ll do well to avoid carrying foods that require refrigeration. If the crew considers this spartan and perverse on our part, a common plastic cooler will resolve the issue.

Worried that we might be concerned about limited headroom, Wittholz drew a hinged cabintop option. And the plans bristle with other alternatives for Corvus: a completely open daysailing version with, as you might surmise, a huge cockpit; a fixed ballast keel, which adds stability (and draft) and eliminates the centerboard trunk; a choice of outboard or inboard auxiliary power; and a standing lug rig to replace the gaff rig.

Lug rigs offer great simplicity, and they are dandy for small boats. Unfortunately, this rendition has been compromised with too much roach and requires battens to support the sail’s after edge. Perhaps we should ask the sailmaker to cut some hollow into the leech and forget the expensive batten pockets.

Close inspection of the lug rig’s drawing reveals a roller-reefing boom. We’re supposed to tuck in a reef by winding the sail around the boom as if it were an inverted window shade. This noble idea enjoyed some popularity decades ago – before we realized that it doesn’t work too well. The hardware is expensive, and sheetleads can be complex and inefficient. Limitations are placed on sail design ( one of the most noticeable being the 90° angle needed at the tack). Because the sail should be hoisted before rolling it around the boom, crew and sail sometimes are exposed to the elements more than with conventional reefing. And, all theory aside, roller-reefed sails often don’t set well. Oh, my. I’d be inclined to replace the roller-reefing goose, neck with a simple rope parrel and spread the sheet attachments forward and aft ( to ease the strain on the boom and to provide a more comfortable lead angle to the skipper’s hand). The money we saved by dispensing with the battens will buy us a row, or two, of conventional reefpoints.

The head and stores occupy the cuddy. The crew lives in the cockpit.

Corvus’s ample transverse framing pro, vides a solid skeleton for her hull, and it will look impressive when set up in our shop – it forms a three-dimensional body plan, really. Those among us who are bothered by complexity, might want to follow Sam Devlin’s instructions for translating designs into “stitch-and-glue” (see WoodenBoat No. 106, page 80).

Wittholz specified ¾” plywood for Corvus’s planking; and, with the tight turns in the forward bottom, he’s asking for all we can expect from the 4 x 8′ sheets. If we’re tempted to apply a thicker bottom, we should laminate it in place. I knew a builder who tried to coerce ½” marine fir plywood into taking these bends. He failed despite copious application of boiling water (poured over bath towels), the efforts of five strong men, and the biggest bronze ring nails in the county. The partially sheathed boat still sits behind his shop, and the builder now makes his living by selling insurance.

Sailing Corvus brings us as close to pure, lazy delight as we’re likely to get in this life. She heels little and requires a minimum of attention from her skipper. Her buoyant hull is handsome from almost any perspective. No matter that the same building time and money could have bought us a bigger (longer, that is), faster boat. No matter that she sails about at her mooring in a maddening fashion. No matter that she won’t lie quietly to the wind while we have lunch. Catboats are, after all, difficult to justify- but they’re mighty easy to like.

-M.O’B.

Plans from The WoodenBoat Store, Naskeag Rd. , Brooklin, ME 04616.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.