Building a wooden boat had finally made its way to the top of my to-do list, and building a small one would be sufficient to satisfy that dream. At the time, we still had a 27′ trimaran and have since moved to a 35′ sloop, both wonderful sailing machines, but a sailing dinghy, capable of rowing, would provide a very different sailing experience. And, if light enough, we could potentially put it on top of our SUV and explore new waters. My son Tyler commented this would be a perfect new hobby for me combining two of my favorite interests: sailing and woodworking. I was eager to get started.

Inspired by the beauty and light weight of strip-built kayaks, I decided I’d use the same method for a sailing dinghy. I scoured the Internet but just couldn’t find a design that got me excited enough to invest a few hundred hours of my time. Then I found the Morbic 12 sail-and-oar dinghy, designed by the French naval architect, François Vivier.

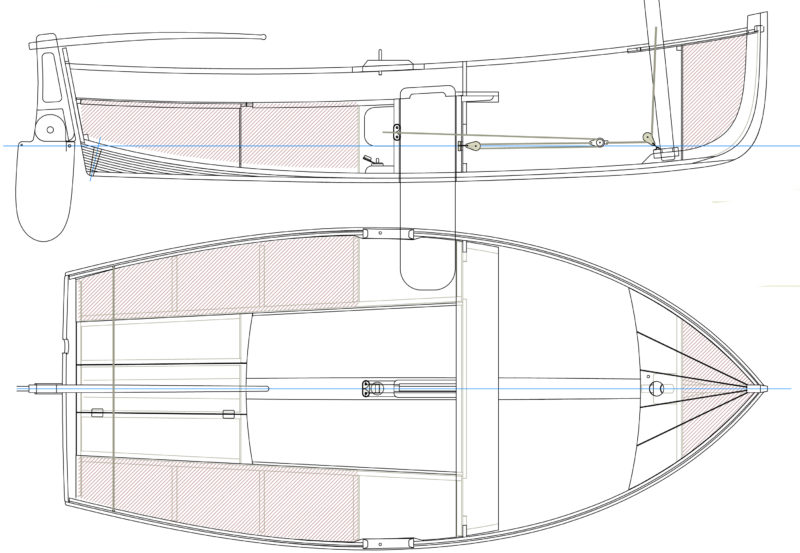

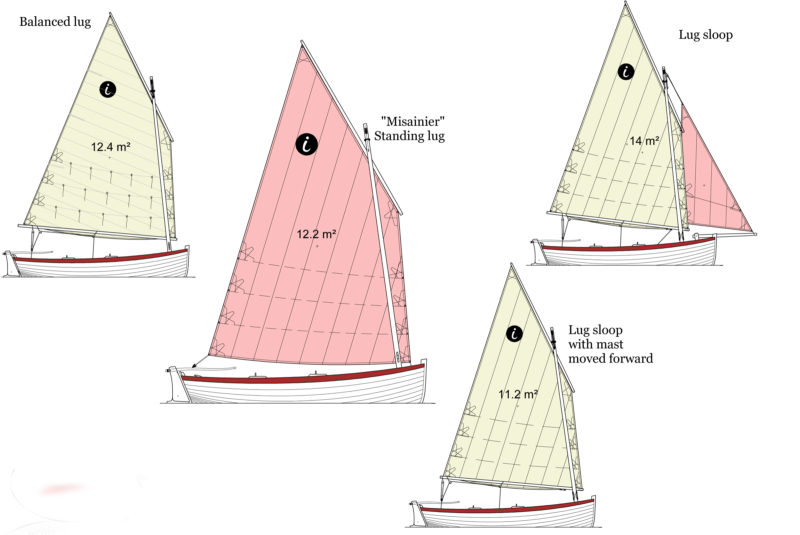

I contacted François in the fall of 2016 to inquire if his Morbic 12, designed for lapstrake plywood, could be built with strip planks. He replied, “Yes, with some modification,” and asked me more about my requirements to make sure the Morbic 12 would meet my needs. After discussions on weight, cockpit arrangement, rowing ability, and rig, he decided a new design would be in order.We agreed to go forward with a Morbic 11 as a lightweight strip-built hull with a balanced lug rig, daggerboard, kick-up rudder, buoyancy compartments, and a bit of dry storage.

François delivered comprehensive plans with more than 60 pages including detailed drawings, a hydrostatic analysis, layouts and dimensions for lumber and plywood components, and assembly instructions filled with 3D color drawings. This would be my first boat build, so I was pleased with the clear instructions in English, and François was very responsive when answering the few questions I had along the way.

Lorena Brown

Lorena BrownThe 70-sq-ft lug sail performs well to windward, as evidenced by GPS tracks showing the Morbic 11 tacking through 90 degrees.

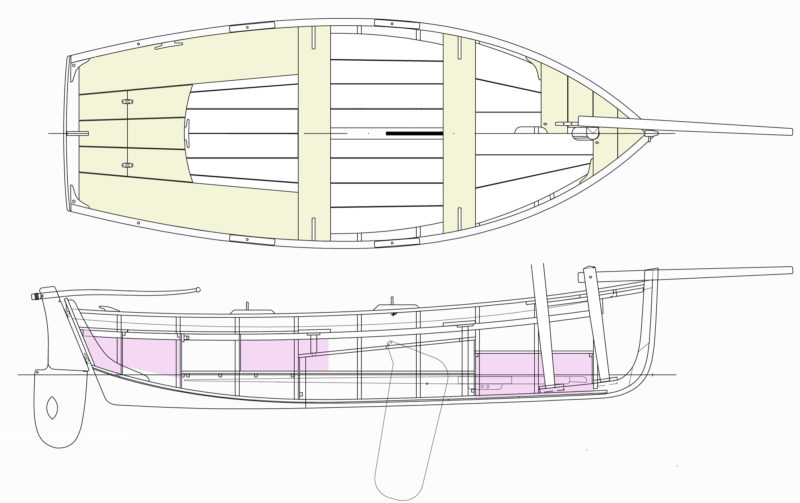

The recommendations for wood species were provided with several options. I used sapele for the stem, keel, and transom glued up with epoxy. These were attached to seven plywood stations on a temporary box frame. The plans do not include instructions for strip-planking, as there are plenty of books on the topic, and the creative decorative aspects are left to the builder. I used a combination of light and dark western red cedar and Alaska yellow cedar with accent strips of sapele and maple. Strip edges were beveled and edge-glued with Titebond II. I wanted to avoid staple and nail holes in the hull, so strips were held in place using hot glue, clamps, and Shurtape CP66, a stretchy and strong masking tape.

I had read plenty of warnings on how labor-intensive strip planking is; even so, I wondered what I had got myself into. Fitting a total of 220 strips was tedious work, but at least no steam was required for bending. I did resort to using a heat gun to coax some of the strips into shape on the deck, as the bends were tighter than on the hull.

After completing planking and adding the skeg and full-length keel, sanding began and the pay-off for building a strip-planked hull became apparent. The smooth-flowing lines on this boat are a thing of beauty.

Lorena Brown

Lorena BrownThe stern-sheets’ center panel is removable to allow the oars to be tucked under the center thwart and stored in the bottom of the boat. Magnets hold the panel in place.

After applying fiberglass and six coats of epoxy and sanding fair once again, I flipped the hull. The temporary stations were removed by slowly softening the hot glue with a heat gun until they could be wiggled out, without damage to any strips. I sanded and fiberglassed the interior, applying a second layer of cloth on the bottom for additional strength.

The bulkheads are of 6mm okoume plywood to save weight, and carefully fitted and filleted. There are three buoyancy compartments with access through 8″ deck plates for dry storage for wallet, keys, and other small items. I made very few changes to the design detailed in the plans, but I did move the bulkhead of the aft storage compartment back about 10″. The original placement is better for weight distribution while rowing with a passenger in the stern, but I thought I’d need a bit more for space for my feet while sailing, so sacrificed a bit of storage for it. As it turned out, I sail sitting farther forward and the original layout would have been fine.

The rudder case, built of laminated okoume plywood, is hollow to reduce weight and give access to the nuts that bolt gudgeons to the rudder. A specific brand and size of pintles and gudgeons are called for in the plans, and I could only find one source for them, at Classic Marine in the U.K. The kick-up rudder and tiller install securely on the hull in seconds and have a solid feel.

Lorena Brown

Lorena BrownAfter the lugsail’s yard is hoisted, the halyard is cleated and the downhaul—a gun tackle with a 3-to-1 advantage and a cam cleat on the daggerboard trunk—tensions the sail.

The laminated Douglas-fir mast isn’t hollow, yet it is light enough for me to slip through the foredeck partner into the step. The step is keyed to prevent the mast from rotating. The yard has an adjustable attachment point to a mast traveler that I built and wrapped with leather. The halyard attaches to a ring on the mast traveler to raise the yard. A downhaul pulls the boom down and aft; raising the aft end of the boom gives the sail a nice, full shape without creases. The downhaul has blocks for additional purchase and a conveniently located cam cleat on the starboard side of the daggerboard case for downhaul adjustment. This makes for a super-easy 10-minute launch.

The plans do not call for lazyjacks, but I added some to keep the boom and yard from banging around on deck when the sail is in a lowered position. They are also helpful for reefing, which only takes a few minutes. To use my reefing system, I release the downhaul, lower the sail, tighten the new tack and clew to the boom by tying off a single reef line to the cleat to the center of boom, make fast the foot to the boom with the five reef lines on the sail, then raise sail again. There are two reefpoints, and this system has been proven on two outings in a little more than 15-knot winds.

I built my Morbic 11 in 540 hours, working on and off over 15 months. It certainly could be built in less time, but this was my first build and I was in no hurry to get it done. I joke (with some truth) that 200 of those hours were spent scratching my head. Woodworking is not my profession; my experience with it is mostly from high school, so the boat is clearly suitable for amateur builders.

Lorena Brown

Lorena BrownA taut luff is the key to getting the best from a lugsail. Having a powerful downhaul that’s handy to the helmsman makes maintaining tension easy.

Like any dinghy, the Morbic 11 feels tender initially, but its 5′ beam stiffens up quickly and is amazingly stable. The boat accelerates quickly due to its light weight, and I regularly achieve speeds of 3 to 4 knots sailing to weather in anything more than about 8 knots of wind. I wondered how well the Morbic 11 would point with the balanced lug, and it exceeded my expectations. GPS tracks show nice 90-degree tacks upwind. We recorded a maximum speed exceeding 6 knots downwind—what a blast!

Sailing the Morbic 11 is a real kick, particularly when singlehanding. One day, sailing downwind in a blow, I suddenly caught a gust of over 20 knots that surprised me. I immediately eased the boom completely forward, over the bow, something that wouldn’t have been possible with a stayed mast, and then steered up to weather keeping the sail luffing with the wind the entire turn. Then, I dropped sail and rowed the short way into the marina, impressed that the Morbic 11 took care of me.

With two of us aboard, I’ll often take the helm and my crew will sit on the ’midship thwart facing aft and handle the mainsheet, shifting position to keep the boat at a proper heel and ducking under the boom as it comes across during a tack or jibe. With a small child joining us, their favorite spot is forward of the thwart, safely out of the way of control lines, with the mast or foredeck to hang onto as needed an unobstructed view forward.

Matthew Putegnat

Matthew PutegnatWith its light weight, the Morbic 11 comes up to speed easily. When sail is set, the oars stow neatly inboard.

When the wind dies, one can always row. The lazyjacks are slackened so that the boom and yard can be dropped all the way to the thwart, and the forward ends of the spars get tucked under the foredeck so they don’t get in the way. The 8′ oars, stowed either side of the daggerboard trunk, are easy to unstow after removing a magnet-held seat panel aft.

The Morbic 11 rows handily being a “classic” French sail-and-oar design. She tracks well due to the full-length keel, and is easily driven because of her light weight. There is a notch on the transom for sculling, but I haven’t learned to do that well yet. It does provide a convenient spot for the mast to lie into while trailering.

Lorena Brown

Lorena BrownA loop of bungee holds the kick-up rudder blade down but lets it pivot over obstructions. A cord on the back side of the rudder stock runs through a shackle to make it easier to pull the blade up when approaching a beach. The sculling notch is offset to allow sculling while the rudder is in place.

Coasting onto a beach is no problem with a daggerboard that lifts right out and the kick-up rudder which stays in the raised position with a clam cleat. A full-length bronze band protects the keel.

The Morbic 11 is designed to take a small outboard, but in Oregon, where I live, that would require registration and unsightly numbers stuck on the hull, so I don’t plan to use a motor.

Many have commented to me that this boat, with all the pretty woodwork and varnish, belongs in my living room and not on the water, but that would be such a waste! It’s a wonderful sailboat, and we get much enjoyment from her the way she was designed to be—on the water.![]()

Gary Brown, husband and father of five, is a family man and recently retired electrical engineer living in Aloha, Oregon. A boater all his life, he has owned sailboats the last 15 years, and loves to race. He kept a construction blog for Hull #1 of the Morbic 11. Gary is in the process of evaluating boat designs for his next build as he continues his woodworking hobby.

Morbic 11 Particulars

[table]

Length/11′

Beam/5′

Hull weight/150 lbs

Sail area/70 sq ft

Draft, board up/6.7″

Draft, board down/27″

Outboard/ up to 3 hp

[/table]

Plans for the Morbic 11 are available from François Vivier for 100 € (about $128 USD).

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!