The Woods Hole spritsail boat is a good example of workboats that became pleasure craft, as happened with so many New England fishing vessel designs. When a colony of summer people sprang up in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, they quickly took note of the vessels traditionally used by the local fishermen. With some modifications to the design to make it better suited for racing, members of the Woods Hole Yacht Club began building a fleet of around 20 spritsail boats in the late 1890s. H.V.R. Palmer, writing about “those handy little boats” in the December 1968 issue of the now-defunct The Skipper magazine, describes two of these old vessels, built by Edward E. Swift between 1896 and 1913, found in a Woods Hole barn in 1965.

The Woods Hole spritsail is, in many ways, similar to the iconic Cape Cod catboat, but with a few distinct differences. The most obvious difference is that the vessel is sprit rigged as opposed to gaff rigged. Many of the fishermen of Woods Hole anchored their vessels in the protected waters of Eel Pond; to enter, prior to the installation of a bascule bridge in 1940, a fisherman would have to pass under an old stone bridge that would require a sailing vessel to unstep its mast to pass underneath.

Josh Anderson

Josh AndersonThe loose-footed sail makes for a very simple rig, but takes some practice to sail well.

“The fishermen of Woods Hole,” writes Palmer, “became so proficient at this, according to old timers around the village, that they could sail to within a few feet of the bridge before lowering the mast—sail, sprit, and all. This rig also made it easier to furl sail when the fishing grounds were reached and it was time to go to work.” The sprit rig, with its unstayed mast and the absence of a boom, allowed this to be done with relative ease. The beam of the spritsail boat is narrower than that of the cat boat, to allow it to be rowed by one person instead of two, since the fishermen of Woods Hole typically worked alone. It also has a slightly deeper draft and increased freeboard for greater seaworthiness in the notoriously rough waters of Vineyard Sound.

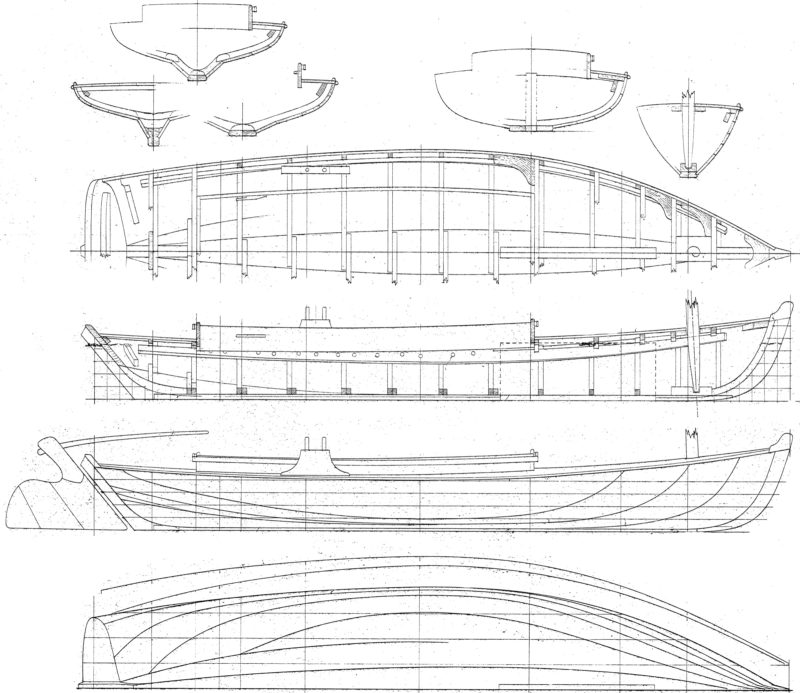

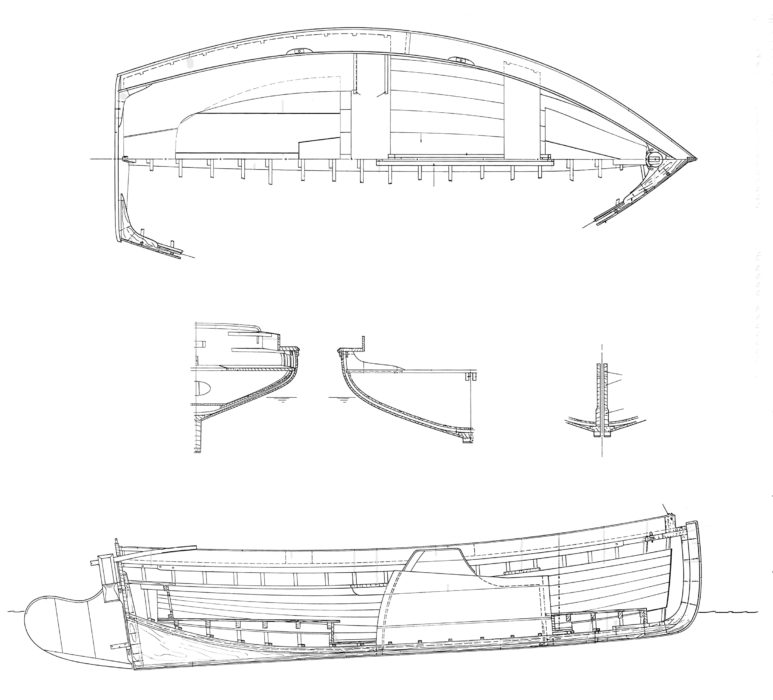

The spritsail boat DEWEY, named in memory of Dewey S. Dugan, a Seattle longshoreman, was built for the Center for Wooden Boats in Seattle in 2000 by the students of Seattle Central College’s boatbuilding program under the direction of the former longtime lead instructor, Dave Mullens. The boat is 13′4″ long, has a beam of 6′, and draws 3′ 6″ with the centerboard down. DEWEY was built to lines taken by David W. Dillion for Mystic Seaport, from the last spritsail boat built by Swift in 1913, one of the two found in 1965. Swift had been building the boat for his brother Helon, who passed away just before it was completed. Lacking the will to launch the vessel, Swift locked it away in his barn, thus preserving the boat in mint condition.

SBM

SBMThe mast is set without head stay or shrouds, making it easier to unstep.

The vessels in the CWB livery fleet are rented to the public year round and get quite a bit of use, so they need to be strong enough to take a beating. DEWEY has been a mainstay at the Center for over 15 years, due in large part to her stout workboat construction. The boat is built with 3/4″ Port Orford cedar carvel planking on 1″x1″ steam-bent, white-oak frames, and fastened with silicon-bronze screws. The similarly beefy stempost of sawn oak measures 2-1/2″ x 5″, and transitions into an equally thick keel.

There is a 5″-wide keelson with 3/4″ floor timbers fastened on top of the keel. The mahogany transom is 1″ thick and has a 1″ x 2″ perimeter frame, and a 1/2″x 1-1/2″ cap. It is tied into the keel with a 1″-thick knee. The centerboard trunk ties into the forward and middle thwarts. Though the spritsail boat is an open boat, it would handle well sailing in a little bit of a sea, as it has a 6″-wide side deck outside of the 1/2″x 5″ coaming. The side deck is supported by 1″-thick hanging knees screwed to the frames underneath.

SBM

SBME.E. Swift built the centerboard trunk in the original boat with an open slot at the top. Enclosing the board keeps DEWEY’s interior drier in rough water.

DEWEY’s wide beam provides a roomy interior, which can comfortably seat four while sailing. The three thwarts are 11″ wide. The mid and aft thwarts tie into two 16″-wide side benches, which are supported by knees. The benches and thwarts sit 8″ above the sole, providing a comfortable sitting height for sailing. The sole covers the entire interior and transitions into a ceiling; even when the boat is heeling, the sailors’ feet never rest on the frames or planks. The 15′ 6″ mast is made of spruce and is 3-1/2″ in diameter at the gate, tapering to 1-1/2″ aloft. The bronze gate in the bow makes it easy to raise the mast—it doesn’t have to be lifted to drop through a partner. The spruce sprit is 17′ 10″-long by 2-5/8″ in diameter and tapered up to the peak of the sail. The luff is attached to the mast with steam-bent hoops.

SBM

SBMThe broad thwarts and benches provide comfortable seating.

The Woods Hole spritsail boat was designed to be easily singlehanded and to sail well in fairly heavy weather without the need to reef. The boat is fun to sail, especially with a bit of a breeze. Interestingly, as a rental boat, DEWEY’s boomless sprit rig is sometimes passed over for the more familiar, marconi-rigged vessels. However, when provided with a bit of instruction, many of CWB’s livery customers find that sailing the Woods Hole spritsail boat is a pleasure.

SBM

SBMUnlike a catboat rudder, where the tiller runs horizontally along the top of the blade, a spritsail boat’s tiller is slipped into a mortise in a rudder head.

The beauty of the sprit rig lies in its simplicity. Setting and dousing the sail is easily done, with the help of a snotter that is equipped with a block instead of a thimble. Once the throat halyard has been hauled tight and cleated, the top end of the sprit is passed through a grommet on the peak of the sail and its foot is then attached to the snotter. To set the sail, the snotter is tensioned—pushing the peak up and aft to stretch the sail out—and then made fast to a second cleat on the mast. Dousing is simply the same operation done in reverse.

Josh Anderson

Josh AndersonHaving the snotter led to a cleat on the mast makes it unnecessary to reach up to the heel of the sprit, but leading the tail end of the snotter aft makes it easier to adjust the shape of the sail without leaving the tiller.

It can take a few adjustments to find the ideal tension for the snotter. This isn’t much of a problem if you are sailing with someone else, but when sailing alone, it can be a bit clumsy and even dangerous to leave the tiller to shuffle forward to make adjustments. It was an easy fix to lead the snotter through a small block at the base of the mast and aft to a cleat installed on the centerboard trunk, where it can now be adjusted without having to leave the helm. This has the added benefit of quick scandalizing; a stopper knot tied at the appropriate spot along the extended snotter line prevents the sprit from lowering too far, which could cause the heel of the sprit to get hung up on the boat.

The sail on the spritsail boat is without a boom, which has advantages and disadvantages. It’s nice not to worry about getting hit in the head by a boom, but it can also be a bit tricky to learn how to trim the sail correctly, especially in light air. When sailing close to the wind, if a boomless spritsail is sheeted in hard to the center of the boat, the clew will curl in and ruin the shape. I found this frustrating the first time I sailed DEWEY, as the boat is fitted with a conventional traveler, which makes it awkward to trim the sail correctly when sailing close to the wind. About 15 minutes into my sail, I discovered that there were two Turk’s Head knots tied on the outermost corners of the traveler that were perfect for hooking the sheet block to. This kept the clew farther outboard, which made a big difference in the boat’s performance to windward.

SBM

SBMThis spritsail boat isn’t yet equipped with oarlocks. The original had rowing stations at the center and forward thwarts with oarlocks mounted on blocks fixed outside of the coaming.

DEWEY lacks the two rowing stations indicated in the plans, and relies upon a canoe paddle or a tow from a CWB chase boat when the wind dies. Next time DEWEY enters the CWB boatshop for maintenance, it will get a pair of oarlocks and a set of oars, as its workboat predecessors originally had.

Overall, the Woods Hole Spritsail boat is a fun and straightforward boat to sail. The sturdy workboat design is roomy and comfortable for a complement of four, while at the same time it is simply rigged and manageable enough to sail alone safely. The design provides decent windward ability for a traditionally rigged craft, and good maneuverability even in the tight quarters of CWB’s busy waterway. The greatest testament to this old workboat design is the handful of people who have discovered what fun it can be to sail this small boat and come down to CWB just to sail DEWEY. After 17 years of use in CWB’s livery, DEWEY is still in great condition, and will certainly spend many more years demystifying the sprit rig and getting people out on the water.![]()

Josh Anderson and Sarah McLean Anderson both attended the Maine Maritime Academy in Castine, Maine. They restored a 25′ Friendship sloop, operated a charter business with it, and spent several years sailing the Maine coast. Josh also attended the Apprenticeshop

Woods Hole Spritsail Boat Particulars

[table]

Length/13′ 4″

Beam/6′

Sail area/127 sq ft, 138 sq ft*

Draft, board up/15″

Draft, board down/2′ 10″

[/table]

*Mystic Seaport acquired two sails with the boat.

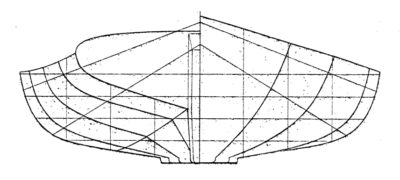

© Mystic Seaport, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, #misc44-1

© Mystic Seaport, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, #misc44-1.

Plans for the Woods Hole Spritsail Boat include lines, offsets, sail plan, and construction details. They are available from Mystic Seaport for $75.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!