SADIE is a Classic 17 that was built by Steve Hewins and his fellow students at the Boat Building Academy in Lyme Regis, U.K. Jacques Mertens designed the Classic 19, around 1990, for an amateur boatbuilder in Florida, and the 17 and 21 followed soon afterward. His company Bateau.com has now supplied a couple of hundred sets of Classic 17 plans around the world, and he thinks about 50 boats have been launched in the U.S. Mertens based the design on a classic hull shape that was common among outboard boats in the 1950s. Unlike today’s deep- to moderate-V hulls, the Classic 17 has a low, 10-degree deadrise, which requires less power to plane but will pound more as the sea builds up. All of the Classic-series boats were designed to go offshore in moderate conditions and make it home safely if the weather takes a turn for the worse.

Steve found that the PDF plans, supplied as an “instant download” by Bateau.com, were very comprehensive—there are even separate metric and imperial versions—and there was no need to loft the boat. There is detailed information regarding every plywood component, including offsets and a thoroughly thought-out nesting arrangement to ensure economical use of plywood. For SADIE it was decided that, as a useful exercise, the academy students would cut some of the parts would be cut by hand, and enter the data for others in a CAD program and have them CNC cut at the Architectural Association’s woodland site at nearby Hooke Park.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorSea trials with SADIE showed that trim improved when some of the passengers moved from the cockpit into the cuddy cabin.

Construction began by setting up a base frame consisting of two longitudinals and four cross braces, all in 8″ x 2″ softwood. The build requires ten sheets of 1/4″ plywood, ten of 3/8″, and three of 1/2″, all in standard 4’x8’ sheets. Steve chose to use Robbins Elite okoume plywood. In addition to the transom—made up of two layers of 3/8″ ply with an American walnut veneer on the outside—there are five 3/8” plywood building molds that serve as permanent bulkheads and frames.

Each of these was set up and supported by two 2×4 softwood timbers fixed to the base frame, ensuring that it was plumb and accurately positioned. The transom is positioned at an angle by the motorwell sides. The two longitudinal stringers in the bottom of the boat, each in two layers of 3/8” ply, were notched into the transom and the four aft molds. There is an optional fore-and-aft mold at the bow, but Steve decided that the bottom and side panels would come together accurately without it.

SADIE’s planking consists of a pair of bottom panels and two topside panels on each side, overlapped. The panels were made up with joined pieces of 1/4″ plywood to get the required length before it was fastened to the molds. The instructions call for butt joints backed by butt blocks, but Steve used a “welding” technique taught at Lyme Regis by boatbuilder Jack Chippendale some years ago. In this case, a bevel 3/16″ deep and 2-1/2″ wide was machined into each of the edges to be joined, and the two sharply beveled edges were brought together resulting in a 5″-wide triangular recess. The void was filled with epoxy and ’glassed until it was slightly proud (resembling a metal weld) and then sanded flush.

Compared to butts, these joints look tidier inside the boat and bend in a fair curve, avoiding the flat spots butt blocks can create. The bottom planks and lower topside planks were fitted, stitched, and taped to each other before being epoxied to the transom and fixed to the molds with temporary fiberglass tabs. The exterior faces of the plywood planking were covered in 450g biaxial cloth and epoxy. Then the upper topside planks were fitted, overlapping the lower topside planks by about 7″, providing a great deal of longitudinal stiffness. Covering the outside of this upper plank in ’glass is optional, and Steve chose not to do so.

The hull was faired and painted, and then a 1-1/2″ x 3/4″ piece of sapele, tapered toward the bow, was fitted along the outside of the chine for extra stiffness and to act as a spray rail.

When it was time to turn the hull over, the temporary fiberglass tabs were cut so that the hull could be lifted off the frames and bulkheads, turned, and lowered onto a close-fitting cradle. It took 10 students to do this, not because it was heavy, but because without the forms to keep its shape, the hull was very floppy and needed careful handling. The chines and centerline were epoxy filleted and taped before the inside was glassed with 450g biaxial cloth and epoxy. The ’glass layers on the inside and outside are structural; plywood as thin and flexible as 1/4″ may be used for planking.

After trimming the bulkheads, frames, and stringers to allow for the thickness of the newly-applied glass, they were installed permanently with epoxy fillets and fiberglass tape. The 1/2″ plywood cockpit sole was fitted, resting on the stringers and on timber cleats elsewhere, and the void below it was then filled with two-part expanding polyurethane foam.

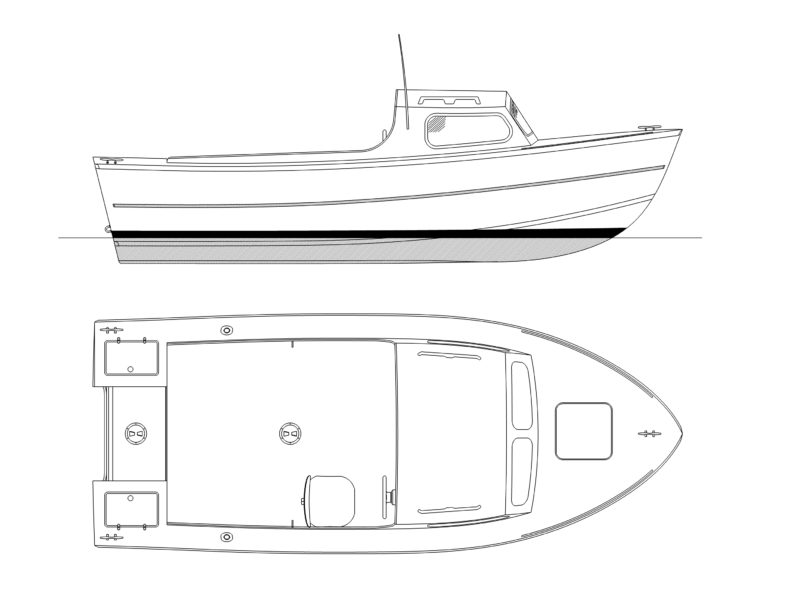

The cuddy cabin was designed with cruising in in mind, and the drawings indicate sleeping arrangements for two. The arrangement here is unique to SADIE and intended for day use.

The plans offer two possible cockpit arrangements but also acknowledge the freedom builders have to plan a different layout. Both of the plan’s arrangements involve side seats, but Steve planned to use SADIE for fishing, and his more experienced fishing friends advised that it would be desirable to stand as close to the edge of the cockpit as possible. So, he fitted a seat across the stern under which the 6.6 US-gallon portable fuel tank and battery would fit.

The deck structure was made up of a beam shelf—kerfed where the bend was particularly pronounced in the forward sections—and carlin, both of 1″ x 1″ Douglas fir. Steve had doubts about the lack of any other structure for the foredeck, so he fitted a 5″ x 1″ Douglas-fir kingplank before laying the 1/4″ plywood decks. (His concerns persisted after SADIE was finished, and he planned to add deckbeams from underneath later.)

Steve strayed from the specified scantlings for the superstructure by increasing the coamings from 3/8″ to 5/8″ (he had some spare 1/4″ plywood, so he laminated this to the 3/8″), and by reducing the coach roof’s thickness from 3/8″ to 1/4″. He had found it too difficult to bend the thicker plywood with its slight compound curvature; the 1/4″ material would suffice because he didn’t expect to ever put any weight on the roof. Four 3/16”-thick acrylic windows with rubber gaskets were then fitted.

While the design called for two berths inside the cuddy, Steve doesn’t intend to sleep onboard, so he fitted a seat to starboard, and to port a stainless-steel-topped galley unit that will accommodate a camping stove.

SADIE was finished with natural wood in various places including a varnished khaya cap for the cockpit coaming, laminated in ten layers where it curves up at the aft end of the coach roof; uncoated iroko handrails; a 2″ x 3/4″ sapele rubbing strake, which had to be steamed over the forward 6′; and 3/8″-thick sapele linings along the hull sides in the cockpit. Some of the sapele was recycled from wood from a church, and coated in Deks Olje No 1.

SADIE’s topsides are finished in Epifanes two-part polyurethane gloss in custom-tinted “Stars and Stripes Blue,” below which there is a white Hempel boot-top and black Jotun Racing Antifouling. The decks, coamings, and inside are coated with Hempel’s Multicoat single-part paint, with Hempel’s Anti-Slip Pearls in the horizontal deck areas.

A 50-hp outboard was designer’s the original recommendation for power; many builders found a 60-hp motor works well. The transom is designed for a 20″ shaft, though modifying it for a different length wouldn’t be difficult.

The plans recommend a 50-hp outboard engine, but Steve noticed in the comprehensive Bateau.com forum that other Classic 17 builders had fitted 60-hp engines; the designer had approved that upgrade some time ago. Steve’s local engine supplier, Rob Perry Marine, had a Mercury 60-hp EFI four-stroke engine at a good price, so Steve went for that.

Steve had also read in the forum that someone had managed to get 32 knots out of a Classic 17, although that was with a lighter two-stroke engine. He hoped that he might get around 25 knots but “isn’t planning to gun it everywhere” and would generally prefer “a nice steady pace” on future trips mostly with his dog Sadie, after whom the boat is named, his girlfriend, and occasionally his parents.

A deadrise of about 45 degrees at the forefoot cuts through chop; at the stern the deadrise flattens to 11 degrees for stability’s sake.

On the day SADIE was launched, the wind was light and there was a slight chop off Lyme Regis. With five of us on board and the engine at 5,000 rpm, SADIE achieved a top speed of 21.9 knots. Steve’s concern that his aft seating arrangement might give too much bow-up trim was proven, and so two of his crew crouched in the cuddy to keep her level. The ride was a bit bumpier there than on the aft seat, so Steve plans to install some internal ballast forward.

The position of the wheel doesn’t give the helmsman room enough on the cockpit sole for a wide and stable stance, so the boat will soon be fitted with a bolted-down seat. The sole is above the waterline, so it is self-bailing.

He also plans to install a seat at the helm—and the three of us who took a turn at the wheel found standing to be slightly precarious. SADIE showed that she has a very tight turning circle: around 2.5 boat lengths at 13 knots and 1.5 boat lengths at 5 knots. In flat water, with the engine idling at 900 rpm, the boat moves along gently at just under 2 knots and is very directionally stable.

Steve was generally very impressed with the detail of the plans. “It all went together beautifully,” he said. “All credit to the designer. He has done a really good job to make sure you can build the boat relatively easily with minimal help.”![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry, and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Classic 17 Particulars

[table]

Length/17’2”

Beam/7’

Displacement at DWL/1,500lbs

Hull draft/8″

Hull weight/850 lbs

[/table]

Plans and kits for the Classic 17 are available from Bateau.com for $90 (digital plans), $110 (digital plans with printed copies), and $4,580 for CNC-cut kit.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!