Peter Knape was once stuck behind an office desk in a soulless building in the business district of Arnhem in Holland. Year after year, his demanding career had sapped both his time and energy. He longed for a quiet life with freedom, and independence. He realized his destiny was in his own hands, and that he only had to muster the courage to make a break.

He took a vacation and traveled to northern Finland where he hired a small boat and set off on a long journey, one that took him far beyond the Arctic Circle to an area that’s almost uninhabited. Life aboard the boat was uncomplicated; it was exactly what he had been yearning for.

It was 1977 when Peter began looking for a boat of his own, and while on another vacation touring England by motorcycle, he made his way to Totnes in Devon, England, where Honnor Marine was building fiberglass Drascombe boats. He had decided a Drascombe Longboat could be adapted to suit the life he wanted to live, but in his discussions with Luke Churchouse, owner of the boatshop, it became apparent that a company geared for production ’glass boats wouldn’t be able to deliver the degree of customization that he required.

Peter was still convinced that a Drascombe would be the ideal boat for him, so Luke suggested a visit with my brother John and me at our boatyard at Yealmbridge. We had been involved with wooden Drascombes from their beginning, and we had the only license to build them of wood. Every Drascombe we built had been customized for each client, so we were in a good position to meet his requirements.

John and I were working when we saw a motorcycle drive up, the rider dismounted, and then came into the workshop. Peter introduced himself, explained his requirements, and asked for our opinions and advice. We answered his questions and then recommended he pay a visit to Ken Duxbury and his wife Brenda at Rock in Cornwall. Ken, who died in 2016, was a prolific writer and a very experienced sailor. He owned LUGWORM, a wooden Drascombe Lugger that featured in many of his writings and books. We felt Ken and Brenda could provide Peter with valuable advice gained from their own extensive voyages in a Drascombe, so after we telephoned Ken to provide the introduction, Peter set off on his motorcycle to meet them.

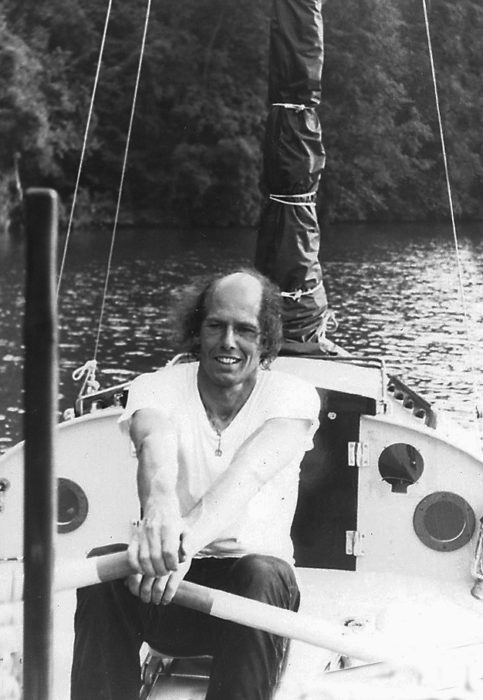

Peter Knape

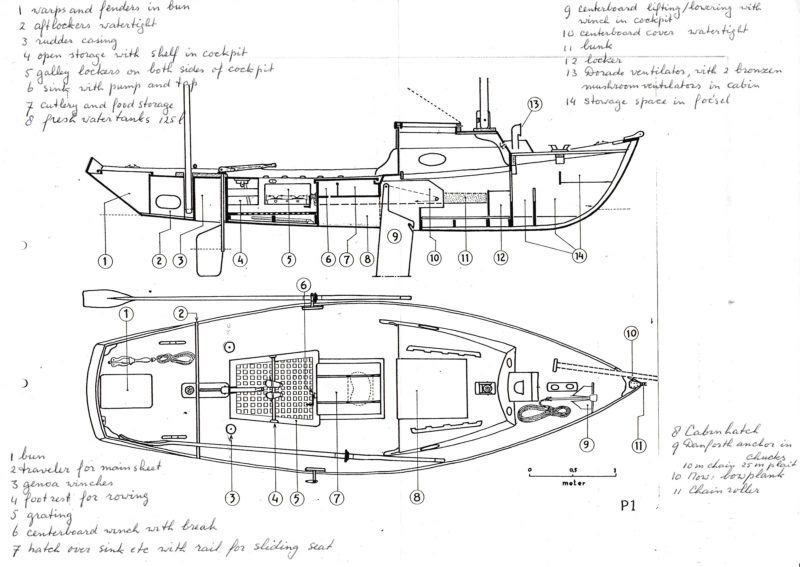

Peter KnapePeter provided the Elliott brothers with detailed drawings and notes for the modified Drascombe Longboat that he wanted them to build.

A few weeks later, a letter arrived in the mail. It began with “Do you remember a Dutchman in blue-black leather who visited you?” Of course we did! Peter wrote about his visit to Ken and Brenda and how they had welcomed him, taken him out in LUGWORM for a sail and a row, and given great advice with enthusiastic encouragement. The visit had fired up his ambition and clarified what was achievable. He now wished to order a highly customized Drascombe Longboat Cruiser from us. He included some drawings to show us the modifications he had in mind.

Before we began building Peter’s boat we had long discussion with him about what would and wouldn’t work, and together we came to a clear understanding of the boat we’d build. A bond of understanding and trust had developed between us. During construction, Peter traveled by motorcycle from his home in Holland, a journey of around 900 miles each way, no less than three times, and even brought his partner Elly Jansen for one of those trips.

LEGOLAS would be radically different from any of the other Drascombes we’d built. It would be a cruising home. The cabin would be shorter than the standard length, and the hull would to appear normal from the outside, but the internal frames, bulkheads, and decks were designed higher to give more room for living and as much storage space as possible.

A sliding seat and long sweeps would be the means of propulsion when not sailing; there would be no outboard-motor well as on other Drascombes because, as Peter put it, “outboard motors are noisy, smelly, and guzzle very expensive fuel.” A hinged cabin hatch and a large dorade ventilator would catch the breeze and make the cabin more comfortable for sleeping in hot weather.

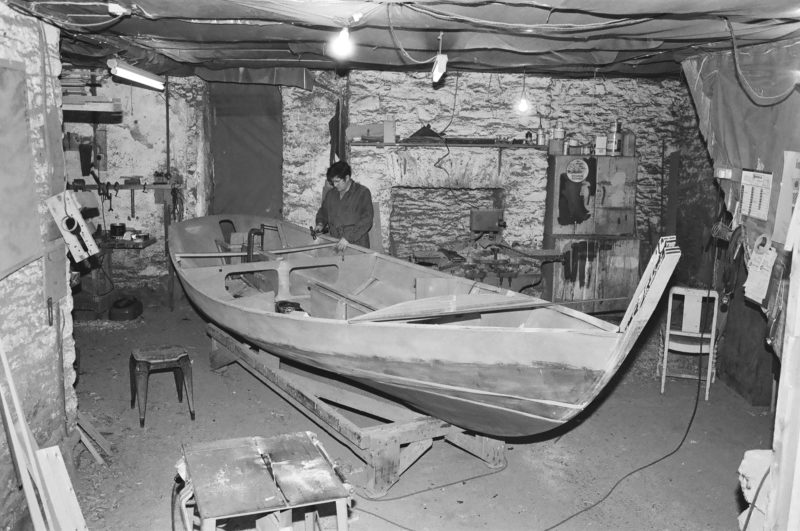

Douglas Elliott

Douglas ElliottLEGOLAS was built here in the Elliotts’ shop and delivered nearly finished, leaving some custom woodworking, varnish, and paint for Peter and Elly to do at their home in the Netherlands.

The manner of building LEGOLAS was the same we used for all of our other wooden Drascombes. The hull is built of high-quality 9mm marine plywood. The frames, bulkheads, centerboard case, and rudder trunk are of 12mm marine plywood. Kiln-dried iroko hardwood is used for floors, gunwales, frame doublers, and stem laminates. The decks were 6mm marine plywood, and the masts and spars were made from Columbian pine or Douglas-fir.

The forward bulkhead, ’midship frames, aft bulkhead, transom, centerplate case, and rudder trunk were all reinforced with hardwood or plywood doublers, and were assembled prior to fastening on the building jig. The rudder trunk was glued and fastened to the aft bulkhead and transom, and the centerboard case was glued and fastened to the ’midship frames. The components are all temporarily secured to the building jig. The hull was built upside down, and the frames are tied together by an inwale, the keelson, and inner stem.

Phenolic resin glues were used throughout the boat, but the frames for LEGOLAS were very different from the standard design, and so the build was about to become an experiment in adaption and innovation given Peter’s very specific requirements for this boat that was to become his home. We planked the hull up to the third strake, and before adding the sheer, we faired and finished the bottom, released the hull from the building jig, and flipped the hull.

This is the point where LEGOLAS started to differ quite significantly from other Drascombes. It’s not an open boat; it has a sheer-level deck instead of benches set even with the lower edge of the sheerstrake. We made a recess in the deck as a footwell for the sliding-seat rowing rig, not something you see on many traditional-looking 21′6″ sailing boats. LEGOLAS would be so high-sided afloat that Peter would have to use a pair of 12′ oars (normally meant to be used one per rower for racing) instead of the 9’ sculls a single rower would ordinarily use.

We dry-fit all of the plywood decking, then removed it to allow access to the interior for painting. We also painted the undersides of the decking before gluing and fastening the panels down. John and I then finished the hull by installing the sheerstrake and the transom return.

We paid particular attention to the fit and finish of the coach roof. The interior woodwork would be visible when Peter was below, and we didn’t want flaws in the joinery. The coach roof had to be strong too, because the front would be fitted with a tabernacle and have to transmit the thrust of the mainmast down to a reinforced forward bulkhead.

With the woodwork completed, we covered the decks in a 16-oz woven roving fiberglass cloth bonded with epoxy resin, which gives extra stiffness to the 6mm marine plywood decking and a durable non-slip finish.

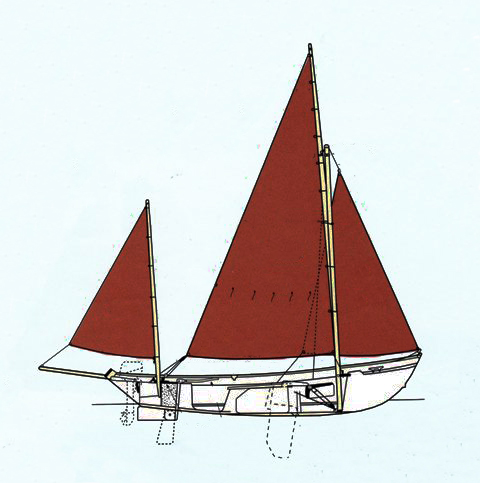

During construction, our overriding aim was always to stay as true to Peter’s vision as possible. I believe we managed to achieve that quite well, because he requested very few alterations. The rig we supplied was a “smack rig,” which consists of a gunter main, a gunter mizzen, a jib, and a flying jib on a bowsprit.

This photograph and those that follow courtesy of Peter Knape and Elly Jansen

This photograph and those that follow courtesy of Peter Knape and Elly JansenThe modified cabin and raised deck on LEGOLAS provided more spacious accommodations than the standard Longboat Cruiser.

In March of 1979, Peter took delivery of the Drascombe Longboat Cruiser we built for him. It was unpainted and had all of the main storage spaces, but the small details surrounding storage and odds and ends were left for him work out. This was to save money, but only in part. There’s no substitute for sitting in the boat and making final decisions for yourself. Peter and Elly finished the boat in Holland and christened it LEGOLAS after an elven character in J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings.

With LEGOLAS finally ready for launching after completion of the painting and multitude of odd jobs, Peter decided that it was time to move aboard and begin to travel. He sold all of his property, stepped aboard just outside of Arnhem with enough money to live simply for a year to a year-and-a-half, and on September 17, 1979, he departed in a general southerly direction on the River Meuse.

His upstream voyage on the Meuse, some 400 miles long, was against a steady 1-knot current. He sailed when he could, and when the wind dropped he brought his rowing rig into action or simply found a quiet spot to anchor and enjoy the solitude. The farther south he traveled, the less wind there was, so rowing became more of a regular duty until reaching Namur, Belgium, a city where the rocks on either side of the river reach around 100′ high, shadowing the wind altogether.

Peter rowed much of the route from the Netherlands to the south of France. Here LEGOLAS is on the Meuse River in Belgium. 1979

A little farther on, near the French border, he lowered the masts to clear the very low bridges, some as low as 11′, so rowing continued to be the everyday exercise and somewhat of a struggle against the never-abating current. It was exhausting work, and discouraging with the knowledge that winter was not far off. But the weather remained unseasonably beautiful for weeks on end.

When Peter thought he’d rowed far enough for a day, he’d pick a suitable stopping place and cook a four-course meal. Rowing burns up energy, so good food was essential, as was rest; this combination of fresh air and healthy living ensured a good night’s sleep, often as much as 9 or 10 hours. Peter was feeling fitter and healthier day by day, exactly what he had wished would happen. It raised his spirits and affirmed his decision to live life aboard a small boat.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

In October, the nights got noticeably colder, and there was a thin sheet of ice on the water every morning in the canal running along the valley at the base of the Vosges mountains. Then it started to rain, making rowing difficult because his hands became soft with the constant drenching. But his journey along the rivers and canals of northeast France continued, every day he went some 15km and through several locks, and Peter arrived at the town of Epinal. Situated 1,000′ above sea level, it was not just the geological peak of the voyage south to the Mediterranean, but a psychological peak. He would no longer have to fight against a current, but could ride with it. His daily distance gradually increased and the weather didn’t get any colder as he progressed southward. Although the rain persisted all the way to Lyon, he had a tent that could be quickly erected over the cabin and cockpit to keep everything dry. A bottle filled with hot water kept him warm whether he was in the cockpit or in his sleeping bag.

The River Saone was flooding, which sometimes made the rowing difficult, but it offered silence and solitude, beautiful scenery, welcoming towns and villages, and safe places to stop overnight.

The Saone delivered him to the Rhône, an impressive river with long straight canals, but it offered few overnight refuges. The distances between good anchorages dictated his schedule, and he often had to stop sooner than he wanted, or worse, he had to continue rowing much longer than he intended. The towns along the river catered to commercial traffic and large boats, so it was also a difficult place to even go ashore to shop for the supplies he needed.

At Avignon, just 55 miles upstream from the Mediterranean Sea, the local rowing club welcomed Peter, wanting to know all about his boat and his journey. They treated him as an honored guest, provided hot showers, hosted him for dinner, and even arranged for a newspaper interview. He was grateful for the hospitality but not interested in the interview. He was making the journey for himself, but his hosts were so kind, it would have been rude to refuse, so he acquiesced.

After the rest at Avignon, Peter left the Rhône and Petit Rhône behind to follow the long-deserted and little-used canals that coursed their way west straight into the Mistral, a northwesterly wind that made rowing impossible much of the time, so he resigned himself to the role of a barge-mule. He harnessed himself to LEGOLAS with a long line, and took to the tow paths, walking for many miles along the route.

On Étang de Thau, a 9-mile-long, 2-mile-wide lagoon, he was surprised by a Force-9 Mistral. Sailing precariously under a reefed main only, he was unable to sail to windward because he had not finished the boat’s rigging. He had put that job off while traveling the canals and rivers, expecting there wouldn’t be much sailing until he reached the Mediterranean. It was a decision that he regretted, as it resulted in a very unpleasant night on the lake. The upside was that LEGOLAS showed her ability during the storm, and it reinforced his confidence in her.

Peter takes to the oars at Sète, near Étang de Thau on the southern coast of France, after a stop to repair the rudder. 1979

At the west end of the lagoon, Peter entered the sheltered water of the Canal du Midi and, just a few hundred yards in, found a hospitable winter berth at the Le Glénans sailing school. It was New Year’s Eve, 1979, and after 100 days aboard LEGOLAS, Peter was fitter, healthier, and felt a very youthful 45 years old. It was the first time in his life that he’d spent three months on his own, and had time to think and evaluate his life. He decided, “I will not return to the circus of over-organised society from which I now feel escaped.” That resolution laid the foundation for an extensive cruise. While in the Canal du Midi, he completed the rigging and got LEGOLAS ready for the long sea voyage that was to follow.

When the spring of 1980 arrived, Peter took LEGOLAS out into the Mediterranean for the first time. It turned out to be very uneventful debut, with only 4 miles sailed in about 8 hours, thanks to the flat, calm conditions that sometimes occur there. Peter traveled east along the French coast and sometimes the sea was mirror calm; other times a screaming mistral tested his seamanship to the limit. Rarely did he have any decent sailing conditions. Rowing the unsheltered waters turned out to be quite impossible; in all but the slightest swell he was unable to keep the oar handles from colliding with his knees. Sculling over the stern was good propulsion, but only for short distances or when steering into harbor berths. Peter passed the mouth of the Rhône river and the cities of Marseille and Toulon before leaving the coast and sailing southeast for Corsica.

The 100-mile passage took four days. The first two days were dead calm, and while Peter enjoyed beautiful peaceful nights under clear, starry skies, he had to stay vigilant for the ever-present danger of passing ships. He didn’t get much sleep. On the second night, he watched a brightly lit ferry pass by in the distance, and it seemed to jump along the horizon with each blink of his eyes. Each blink was, in reality, a minutes-long sleep. On the third night the moon was obscured by big clouds and a southeasterly rose rapidly to a Force 7 blow. Peter had no option but to stream a sea anchor from the bow to ride out the storm that night. The storm was followed by a beam-on mistral which hurried LEGOLAS along under shortened sail to Calvi on Corsica’s northwest coast.

Peter, after his solo crossing from France, sailed the coast of Corsica under full sail. 1980

Sheltered coves along the island coast provided anchorages for the night, and Peter enjoyed the benefits of peace and quiet. With the good food and abundant water supplies that he carried aboard LEGOLAS made it an easy and inexpensive way to live. When he reached the southern tip of Corsica, he stayed for a while in the fjord-like harbor of Bonifacio. Elly joined him there for what was to be a few weeks holiday, but discovered, as Peter did, that life onboard agreed with her. She never left. The two sailed across the Strait of Bonafacio, the 7-mile gap between Corsica and Sardinia. They had planned to continue south and make the 112-mile crossing of the Mediterranean to Tunisia, but the weather had deteriorated as summer came to a close.

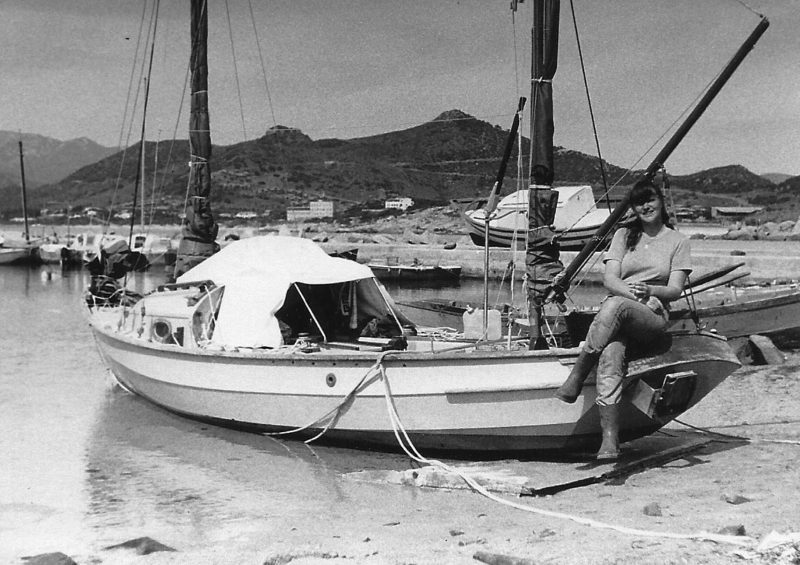

Elly joined Peter at Villasimius, a coastal village on the south end of Sardinia. 1981

They hibernated in the south of Sardinia, and by springtime, their funds were rapidly diminishing. Peter took various jobs to bring in a little money. Repairing wooden boats and old engines for the local fishermen brought in a little income—they too had little money—but in his free time Peter found he had a talent for drawing and painting with watercolor. The tourists at the marinas and harbors provided a ready market for his art, and they paid well.

Soon Peter had enough money to buy a secondhand outboard motor. He had been against having an outboard at the beginning of his adventure, but he was now responsible for Elly’s safety. And the unreliable wind often made planning ahead impossible. They needed to be sure that they could find a place to spend the winter and find jobs. Where most Drascombes have a motorwell, Peter had a gear locker, so he mounted a bracket on the transom to carry the outboard motor.

LEGOLAS lines up on the northern entrance of the Corinth Canal. Nero, the Roman emperor, took a few swings of a pickax in 67 A.D. to begin the digging of the canal, but the project wasn’t successfully taken on until 1881. In 1893, the 300′-deep cut opened the shortcut through Greece.

Peter and Elly sailed and rowed the 155-nautical-mile crossing from Sardinia to Sicily in five days. With two aboard, they could schedule watches and stay alert during the night. They then cruised aboard LEGOLAS some 1500 miles along the sheltered coastline of Italy to Greece, arriving at the island of Rhodes just before Christmas. A few days later they found work on a big charter boat, varnishing brightwork under the warm Mediterranean sun. They worked for the charter company until spring and resumed their wandering by sailing to the coast of Turkey and then making the 36-mile crossing to Cyprus.

Rising above LEGOLAS are ruins near the village of Lindos, on Rhodes, the largest of Greece’s Dodecanese islands. August, 1982

They rounded the island’s west end and stopped at Larnaca on the southern coast for the coming winter. It was a good decision: the people living in the land of Bacchus and Aphrodite were relaxed and friendly, and work was easy to find. Peter and Elly lived comfortably aboard LEGOLAS. They decided to enlarge the rig to make better progress in the weak winds that they had so often encountered. Peter built a new mast that was 4’ taller, and a local sailmaker made a 90-sq-ft light-weather genoa. Flown high from the masthead, it was a great success.

While on Cyprus, LEGOLAS got a new taller mast and a light-weather genoa to improve sailing in light air. Note the pop-top cabin roof.

After Cyprus, Peter and Elly headed LEGOLAS west again, and the following year roamed the sea around Turkey. When they came ashore for the winter, they rented a house on the beach and pulled LEGOLAS ashore in a mandarin grove next to the house. Having a bigger roof over their heads was a good choice, as it turned out to be a very wet winter. They took advantage of the space and store all their gear in their temporary villa while they repainted the boat’s interior.

Peter and Elly came ashore at Kastilllorizo, a tiny Greek island 75 miles due east of Rhodes, but just a mile and a half off the coast of Turkey. 1982

In the spring, they started sailing early and toured the many Greek islands just west of Turkey. The Dodecanese archipelago offered some of the most interesting places to visit—the 12 large islands and the scores of islets scattered among them offer secluded coves, inviting beaches, and everything from prehistoric cave dwellings to cathedrals and castles.

The voyage from Turkey to Elba on Italy’s northwest coast proved to be the most difficult sailing during the whole eight years of their Mediterranean tour. After rounding the toe of Italy’s boot, LEGOLAS struggled against the prevailing westerly and north winds, and was slowed by both the short chop and the flat calms of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Peter and Elly tried sailing at night to make use of the predictable northeasterly offshore wind, but it would usually die in the middle of the night as the temperature dropped. Then the lulls made it difficult to get to an anchorage. Italy’s west coast is beautiful, but offers little in the way of shelter for a small boat. The sailing was very demanding, and after around six months of being on the move almost daily, the couple stopped frequently to keep morale high. Upon reaching the island of Elba they chose Portoferraio as the best port to spend winter.

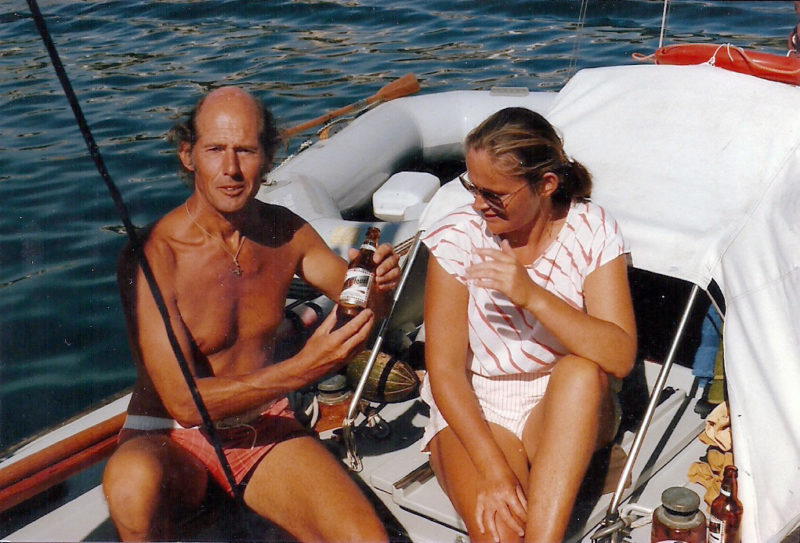

Peter and Elly take a break at Ibizia, the westernmost of the Balearic Islands, 47 miles off the Spain’s mainland coast. 1986

In the spring of 1987, the cruise continued to France, Spain, and the Balearic Islands. Peter and Elly enjoyed their adventures in the Mediterranean aboard LEGOLAS and were planning to continue through the Straights of Gibraltar, the Gulf of Cadiz, and on to Portugal. However, fate took a hand in Elba when Peter lifted too heavy a weight and injured his back. His recovery while still aboard LEGOLAS took four long months, during which he couldn’t sail or work. Gradually he was able to take a few short sails, as long as he avoided lifting and bending over. The biggest problem was getting in and out of the bunk in the small cabin. There was only sitting headroom, and standing up meant painful stooping. He and Elly had to make a difficult decision. Giving up sailing and the freedom it offered wasn’t an option, so they pointed LEGOLAS toward Holland and to sell her and buy a bigger boat, one with headroom and more living space. Finding work to fund the major change would be easier in Holland.

Soon after they set their course northward through France, their old and unreliable outboard motor succumbed to the very salty water of the Mediterranean; parts of it just crumbled into the sea. They had enough money to buy a new engine, a quiet four-stroke 5-hp that sipped fuel, vastly different from the old, rackety 6-hp two-stroke that gulped gas at an alarming rate and spewed a trail of blue smoke—so at least some of their journey home would be easier on the ears and wallet.

With her rig down, LEGOLAS motors north along France’s Canal de l’Est, bound for home in the Netherlands. 1987

Sailing upstream on the Rhône was an exercise in patience—fast-flowing water under bridges and in canals approaching locks almost brought LEGOLAS to a dead stop at times—but they arrived quickly enough at Lyon and from there, the journey north along the chain of rivers and canals was quite pleasant. They enjoyed good food and lovely summer weather; the peace and quiet of the River Saone and the Canal de l’Est (now known as the Canal de la Meuse) turned the final part of their adventure into a relaxing holiday.

Peter had expected to be cruising for a year to a year and a half, but LEGOLAS finally returned by water to Arnhem, Holland, on September 14, 1987, just three days shy of an even eight years of cruising, having logged more than 9,000 miles.

Peter Knape sold LEGOLAS in 1989 to Johannes Jonkers Nieboer. He painted her Navy-ship gray, and together with his partner Roos Goverde from Utrecht, sailed her until 1992. Roos took sole ownership of LEGOLAS in 2001, and life changes left LEGOLAS sitting on a trailer in a covered barn since then. She is not being sailed, but she has not been forgotten.![]()

Douglas Elliot lives in Plymouth, England, where he and Susan, his wife of nearly 48 years, raised three daughters. In 1968, working with John Watkinson at Kelly and Hall’s boatyard in Devon, England UK, Doug delivered the first production wooden Drascombe Lugger to the London Earls Court Boatshow. The boat sold within 20 minutes of the show’s opening. Two years later Doug’s brother John was granted the license to build Drascombes in wood. Doug joined him in building the custom Drascombes until John’s unexpected death at the age of 47 in 1980. Doug built a Drascombe Peterboat 4.5 meter under license from John Watkinson. It was the last Drascombe he built. He owns the Drascombe Scaith FOOTLOOSE, a boat he built for John Weller in 1978 but bought back a few years ago. Now 70 years old, he keeps his hand in with a few repair or modification jobs from time to time, and maintains a keen interest in boats, wooden Drascombes in particular. He regularly contributes to The Drascombe Association website forum and the DAN magazine, as well as the Dutch Drascombe Owners website the NKDE, and has occasionally written articles for boating magazines.

Afterword: Peter Knape passed away on January 22, 2022 with Elly at his side.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.