It was the spring of 1988, the year I turned seven, and Dad was restless. Mom was happy on our little homestead. Dad had built a log cabin for us on the hill at the north end of the family property, as well as a blacksmith shop, a sawmill, a henhouse, goat barn, horse barn, picket-fenced garden, and other accoutrements of the homesteader, but he was growing bored with farm life.

photographs courtesy of the Blake family

photographs courtesy of the Blake familyFrom the cypress logs to the stone chimney, Dad built every inch of the cabin where I spent my childhood. Mom’s baskets are piled on the front porch and my pet deer is visible next to them. The baskets went to the fair for sale, the deer did not.

The goats were in milk, the front porch was stacked with baskets Mom had made for the county fair, and she was happily painting in her studio when Dad announced that he was going to build another boat. His last boat, a Block Island double-ender, was christened MERRY SAVAGE, a play on his great-grandmother’s maiden name, Mary Savage. Dad had sailed that boat along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico for a few months, and then she languished around the house for a few more before being sold to a young man from Maine. This all seemed a trifle foolish to Mom, so when Dad said “I am going to build another boat,” she responded, “We will have to actually use this next one, and it should be for the whole family.” She would regret that statement several times over the next few years.

The old Model-A John Deere tractor was parked next to the mill to power the big circular saw. My dad and uncle must have been taking a break for lunch, otherwise and the sawmill would be running and one of them would be riding on the carriage.

Dad thought about the design for a few months, made a few half models, sat down at the drafting table, and the idea for a new boat was born. Based loosely on a Portuguese 16th-century caravela redonda but cutter rigged, the MARY SAVAGE would have an overall length of 31′, a beam of 8′, and a draft of 32″. The name, at my mom’s request, was the proper spelling for my great-great-grandmother’s name. We started by calling the boat the MARY SAVAGE II, but eventually we just referred to her as the MARY SAVAGE. Dad was hoping we’d sail down the Mississippi River, take the Intracoastal Waterway to the East Coast, and then decide whether to head for Maine or the Caribbean. I don’t think Mom took him seriously.

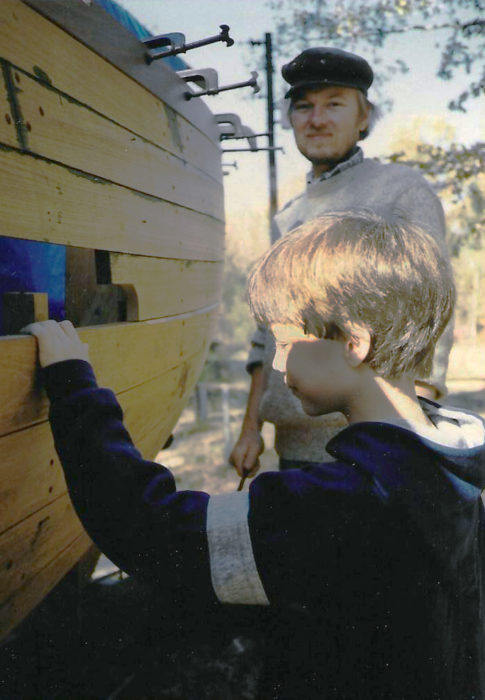

When I wasn’t in school, I’d often help Dad with the boatbuilding. He taught me how to drive cotton roving in a seam and how to buck rivets.

Soon Dad and the old Model-A tractor were out in the woods, felling timber for the new boat. He selected black locust for the timbers and the planking to the waterline, sassafras for work above the waterline, and walnut for trim. After the logs were skidded from the woods, the tractor was flat-belted to Dad’s sawmill and he and my uncle cut, stickered, and stacked the lumber for the boat.

The planking up to the faintly visible red line was black locust; above it was sassafras. I imagine even if the MARY SAVAGE were ever left abandoned to rot away, the lower hull would still hold together.

Dad built the MARY SAVAGE outside, so every night she would be covered in blue tarps and every day she would be uncovered and the work continued. As the boat came together we had many visitors; people came from all over to see the eccentric folks who were building a boat near the goat house in the little cabin on the hill. Some were encouraging, and some simply shook their heads in disbelief.

Before the boat was finished, I spent many afternoons on board, sailing imaginary seas. The fo’c’s’le would be my quarters when we eventually got underway. There was one port that faced the after cabin and a clear panel in the hatch to let light in.

For several years it seemed as if nothing would actually happen. Life went on as usual; Dad worked on the boat, Mom continued to make baskets, weave, spin, sew, and paint, and I went to school. Then in the spring of my 10th year, the paint was on, the crowd was gathered, including our Episcopalian priest, and the boat made its way to the bank of the Yazoo River for launching, blessing, and party. A bottle of champagne was smashed on the bow, the priest blessed MARY SAVAGE stem to stern, and into the river she went.

MARY SAVAGE is ready to be taken to the river to meet the water for the first time. I am aboard to give advice and stay out of the way.

There were weeks of work to do after launching, but my world had changed. We were renting our house, I was leaving school, the animals were sold, and the goodbyes began. Despite assuring my fourth-grade class that I would return by fifth grade with a suitcase of gold (I was reading Treasure Island), I began to worry. If I was worried, Mom was a wreck. She had not expected Dad to complete a boat big enough for the family in such a short period of time. I think, in a way, she hoped the project might take forever.

At the Vicksburg waterfront we were preparing for our voyage. I stand in HAPPY COCKROACH, the ship’s boat, ready to ferry friends and family.

We took up residence on the boat at the Vicksburg waterfront while Dad made final preparations. We had many visitors, and I ran the official ferry in the ship’s boat—a little 7′ scow stowed on the after cabin roof when it was not being towed behind. Mom called it “BRAIN OF POOH” as a reference to A.A. Milne and perhaps a slight dig at the builder (Dad), but, as she was my boat, her real name was HAPPY COCKROACH. As a ferryman I only lost one passenger, but it was not really my fault. He was a rather large man and unsuited for such a small boat. He managed to swim ashore bedraggled, but otherwise unharmed.

With the final preparations made, I put on the best bold, able-seaman pose that I could manage.

The day finally arrived for us to leave the Vicksburg waterfront. It was mid-April 1991. There was a huge party. It seemed as if the whole town had come to see us off. Goodbyes said, we boarded the MARY SAVAGE; Dad went below and spun the flywheel on the one-cylinder Volvo diesel. We set out southbound. The bridge at Vicksburg, spanning over a mile, seemed to rise up forever as we passed underneath. I said, “Look Mom, a gateway to another world!”

The Mississippi river stretches before us. Our old life lies behind and adventure lies ahead.

Just then, as if an omen of various mishaps to come along the way, our friend Tom, who had joined us for the first day’s travel, kicked over a can of paint that Dad had been using to touch up earlier that day. It should have been stowed, but the party and the champagne had interfered with his good seamanship. Tom began scrubbing the deck like a madman; Dad looked up and down the river for traffic, and told me to take the helm so he could help Tom get the last of the paint off the deck. I steered through the portal to other lands. Life would never be the same.

The river was in flood stage when we left Vicksburg and the current mid-river was close to five knots, so we made fast passage to our first anchorage. About thirty miles below Vicksburg is Yucatan Lake, a large oxbow. Usually you cannot get from the river into the lake, but during high water you can cross a revetment and slip through the swamp. You must be careful not to let the water fall, however, or you will be stranded until the next high water which could be up to a year later. All eyes were on the depthsounder as we slipped over the top of the revetment. There was a brief moment where the depth leapt up rapidly but the sounder stabilized at 9′, and as we crossed over, it rapidly read deeper and deeper waters.

Tom owned some property on the edge of this mostly wild lake and had left his ancient Volvo parked at the water’s edge. He headed for home, but for the next week or so he would bring us food and supplies while we got used to living on board the boat away from the amenities of civilization. We were alone in our new boat.

My cabin was before the mast. I had a bunk, a little shelf for my books and personal effects, and a bench under which spare sails were stowed. At 7′ in beam and 7′ in length, the three-sided fo’c’sle didn’t have much room, but I had my own hatch and skylight, a 12-volt, flush-mounted ship’s light, a ventilator for fresh air, and a porthole that looked out on the cockpit amidships.

I started playing violin when I was 4 years old. During our voyage, I had to keep practicing both onboard and ashore. I complained sometimes, but I am glad now that I kept playing.

Shipboard life took some adjusting, and two amusing things happened while we were on the lake. We had an icebox in the galley for fresh food when we were near a town and could get ice, but in the wilderness, everything had to be dried or canned. Dad and I both loved deviled ham, so we ate can after can of it, with crackers, on sandwiches, or just out of the can. By the end of the week we had tired of it, and by the end of the voyage I had grown so sick of it that for 20 years afterward I could not abide the smell of deviled ham.

The second thing occurred on a day that Tom came to give us a ride to the grocery store. When we returned with our goods aboard the ship’s boat and approached the MARY SAVAGE, there was a squeak from her stern. “Tell Nick to not turn around,” Mom’s voice came from somewhere near the rudder. Alone on the boat, Mom had decided to take an afternoon swim. She neglected to allow for the fact that the gunwales were quite high on the MARY SAVAGE, and she did not leave a rope to climb back aboard.

She had found a place to sit on the rudder, and Dad helped a very soggy Mom, without a stitch of clothing, climb back over the gunwale while I dutifully stood off in the ship’s boat. The seams in the rudder had been recently tarred, so it was some time before she managed to finally get clean. This was made more difficult by the fact that, although there was a head across from the galley, there was no shower belowdecks. One of those black plastic bags with the shower head was run up the mast and if there was sun, a big if, you had 4 gallons of warm water. All private bathing was done with sponge and bucket in the cabin.

The water level in Yucatan Lake had begun to fall the following week. We said goodbye to Tom and slipped over the revetment and back into the river. We were bound for Natchez where Dad had stayed on a previous trip, but the moorings at Natchez had changed and small boats could no longer dock nearby. With darkness falling, we had to continue down the river and take shelter in a muddy bayou that stank of oil. It began to rain.The next morning, we realized that there were several oil wells on the bank just up the bayou. It was still raining and the mosquitoes were out in force. We set out as soon as possible to escape the smell and the bugs. Dad, knowing that the Mississippi gets more dangerous below Natchez, had decided that we would lock into the Atchafalaya. With the speed of the current and the Volvo’s help, we could just make the trip in a day.

My parents, Phyllis and Daniel, now look so young to me in this photo. Dad has the helm and Mom is enjoying the breeze. Summer is not yet with us.

I thought we should go right down the river to New Orleans, but my opinion changed that morning. We had already passed several tow boats pushing barges up the river. Many of these tows push a load five barges wide and seven long. That’s 175′ wide and 1,400′ long, and the captains’ capacity to see anything small and their ability to maneuver quickly became practically nonexistent. Some of the towboats had 10,000 hp and their wake was incredible.

Fortunately, it is a big river. We had been rocked around occasionally, but we were never in danger until about 30 miles below Natchez. Two towboats each pushing 5×7 loads of empty barges were headed up the river, and one had decided to pass the other. We could not get too close to the banks because of the rock dikes, and it was unwise to pass between the tows lest we get flattened between two walls of steel. We hugged the bank as close as we dared and came within 150′ of the closest towboat and its barges. That captain had decided that he did not want to be passed by the other tow and had opened his throttle wide. When his wake hit us, every unsecured item below and some of the secured ones ended up on the floorboards in a mighty crash. The rock dikes not 50′ away looked like rock jetties during a hurricane, with waves breaking and spraying over the top. Finally, the MARY SAVAGE ceased to roll and we continued downriver in a shocked stupor as the two tows continued to race each other up the river.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

The lock to the Atchafalaya was not very far away. We simply needed to get by the Old River Spillway. During flood stage the gates can open and divert an enormous amount of water into the swamp. This keeps the lower reaches of the river from overflowing and drowning thousands of taxpayers. The river was in flood and the gates were open. The spillway looked like a giant mouth full of gapped teeth cut into the levee. We hugged the far shore while we passed by. The Volvo sputtered and died just as we came in sight of the spillway. Dad used the momentum of the boat to steer away from the spillway and into the flooded trees on the far bank. We lassoed a willow tree top and tied up while Dad went below and restarted the engine. It coughed a few times and started right up. We cut loose and passed the spillway.

The Mississippi was finished with us, and we with it. We locked into the Atchafalaya just a few miles farther down and drifted into the deep swamp that covers such a huge part of the state of Louisiana. The mood lightened for the first time in three days. We had survived our time on the big river.

We passed a few tows on the Atchafalaya, but they were usually pushing one or two barges, not the like the behemoths of the Mississippi. In Simmesport we resupplied and Dad lowered the mast in its tabernacle to get under the bridge just below the town. As we headed farther south, we entered a different culture. Southern Louisiana has its own flavor, and the people who live there are uncommonly hospitable and generous. This is not to say that some of the folks we met were not rough around the edges, like the nice man in Simmesport who happily gave us a ride to a dumpster even though he couldn’t understand why we didn’t just chuck our garbage in the river, or the pregnant teenage girl who sat on the dock and yelled her whole life story to Mom even though we were moored 30’ away from where she sat with her toes in the muddy water. On the whole though, we were simply struck by their kindness to us.

About 40 miles north of Morgan City, by far the largest town on the Atchafalaya, we anchored up a bayou late one afternoon. It was near the end of April, but the day was unusually cold. During the hot days we would have been using the Primus stove, but that evening we were heating up cans of soup on the wood-burning Shipmate stove in the galley. A young fisherman came by in his plywood fishing skiff to marvel at our boat. He had never seen anything like it before. We asked him how far by water we were from Morgan City. He had never heard of it. He had never been outside a 20-mile radius of his little fishing village deep in the heart of the swamp. The next morning before dawn, we heard a thump on the deck. When we went to investigate, he was just disappearing around the bend in his skiff, and on the deck sat a 20-lb sack of live crawfish, part of his morning’s catch.

At Morgan City, we took on water and fuel then docked next to an old sailboat with a scraggly but friendly character who invited us for dinner on his boat. His name was Ralph, and he was writing a science-fiction novel about aliens. Ralph had a small dog that spent all its time leaping from seat to seat and barking at the bilge, which was inhabited by crawfish and crabs living in the bilgewater. Ralph was generous with what little he had, and the next day as we were leaving he was standing on the deck waving goodbye. “Yip, yip!” was still coming from belowdecks.

Beyond Morgan City, the water turns brackish, and by the time we made it to Houma, Louisiana, you could tell that the Gulf was influencing the rivers and waterways. The tide rose and fell, we could catch blue crabs in the bayous, and the cypress swamp gave way to an endless marsh. Our cousins from Louisiana came to visit us and brought our cat, Luciano. We had left him with them before we set out. Getting him shipboard was Mom’s idea. I think she wanted something familiar and homey, but the cat never got used to being on board. Luciano, named after the opera tenor Luciano Pavarotti, was a big, handsome cat not used to privation. He spent most of his time in the engine compartment between decks and feathered the old diesel’s oily surface with cat hair.In Houma, some folks gave me a small shrimp net to drag behind the boat, and gave my parents an ice chest full of boiled blue crabs. We asked how we could return the ice chest, as it was a quite nice one, but they just laughed and sent us along our way. We pushed southeast through water hyacinth that chokes the waterways and canals in southern Louisiana, and dined on blue crab while enjoying some of the finest weather thus far. It was May, the skies had cleared, the water had cleared, and I could smell the salt sea in the air.

Beyond the confines of the Mississippi River, the MARY SAVAGE sailed along the Gulf Coast with just the gaff main and the staysail set. The boat had a bowsprit and a jib but 90 percent of the time we sailed without it.

As we came into the bay that lies behind Grand Isle, Louisiana, the wind became consistent for the first time. We had tried the sails on the river, but usually had to lower them quickly as the wind would die and the current drove us somewhere we did not want to be. Here though, as we broke through the endless marsh and into the bay, we raised the gaff main, staysail, and the jib on its retractable bowsprit. We made good time all morning out to Grand Isle.

At the time, Grand Isle was a collection of houses on stilts, fishing boats, and some of the friendliest folks we had yet met. I hear it is now a favorite spot for Louisianans to keep a second home or camp and has grown considerably. I hope it has maintained its attitude toward life.

At about noon we dropped the sails and headed into a rather fancy marina on the east end of the island. Two young attractive girls were standing on the dock ready to take our lines. “How much per night?” Dad said. “Only $27,” said one of the girls as I started to throw her the bowline. “Hold that line!” said Dad. “We will anchor out.” The girls looked disappointed. We were on a very tight budget during the trip; Dad had allotted $100 a week to take care of all necessities, groceries, fuel, anchorage, everything. As we left the marina, a small boat with three men aboard approached.

“Where bound?” a rather round man with a big brown beard asked. “Safe harbor,” said Dad. “We are pirates,” he said, “and if you let two of us board and sail with you, we will take you to a safe harbor.” Mom was worried a bit about the possible literal interpretation of “pirates” but Dad laughed and two of the three pirates came on board. They did bring rum, and they did tell me a whopper of a tale about a shrimp boat hauling a chest of silver up in its nets, but Grand Isle was the stomping ground of Jean Lafitte long ago, and even in those days, the pirates were of a rather high caliber.

Our pirates were particularly taken with the MARY SAVAGE and admired the ship’s wheel and all the blocks, cleats, pulleys, and sheaves. They were impressed that Dad had made all of these things as well as the boat itself. We sailed on a beam reach with a fresh wind, fresh enough that the gunwales in the cockpit surged with water on the leeward side when a particularly strong puff launched us along.

We sailed all the way to the west end of Grand Isle and put in at Cigar’s Marina. Dad was afraid we couldn’t afford it. “We will pay for your berth if you don’t have the cash,” the brown-bearded pirate said, “but Cigar’s is only $3 a night anyway.” Indeed, Cigar’s marina was cheap, clean, and friendly.

While we were there, we saw the pirates several times, but we also met several other locals. Having heard about us from our mutual pirate friends, a man we had never met handed Dad the keys to his car and said, “You might want supplies. I am not using the car right now, so take it and get what you need.” Another couple came on board to see the boat, and, after inviting us to a party at their house, said, “We are going out of town for the week, stay at our house while we are gone!” We were not allowed to buy one meal or one drink the entire time we stayed at Grand Isle.

I am making my way to catch bait with my cast net in the silver bucket. I always enjoyed the look of the windows Dad made for the aft cabin. The little scow, HAPPY COCKROACH, sits on the dock awaiting its captain.

I was watching with great interest as a fisherman used his cast net. He showed me how to cast, and the next morning there was a little 4’ net in a bucket sitting on deck with a note saying, “For the young fisherman.”

We stayed longer than we intended, but eventually we had to head east. I think Dad was beginning to feel guilty that he wasn’t allowed to pay for anything. We tracked down the manager of Cigar’s and paid our pittance for the week. There was a good breeze again, and we struck off for Empire.

Empire isn’t the end of the line headed south from New Orleans, but it is getting close. The folks in Empire were very friendly, but I don’t remember the town fondly as I got violently sick there. I had been cast-netting using a technique that involves holding a piece of the net in your teeth. It’s a good technique, but should be used in clean water. The muddy, marshy backwater was home to 50 fishing boats, most with questionable sanitary equipment, and I came down with some form of dysentery. We were 90 miles from any medical help and I could not keep fluids down or up. My parents gave me gallons of water with sugar and a bit of salt. This is the treatment used by the World Health Organization in places where there is no medical assistance. I slept on the bench in the after cabin below Mom’s folding berth for several days. I still remember looking up at the rope netting under the bunks and wishing I was safe back in our little cabin on the hill.

Just before the point when I would need to go to New Orleans to be hospitalized, I managed to get down some saltines. The next day I was a bit better again. Dad made the decision to go on with the voyage and we locked across the Mississippi river into Breton Sound. I was feeling much better, but both Mom and I were at the breaking point.

Breton Sound is shallow and often gets a south wind that builds up a ferocious chop. The weather report was advising small craft to seek shelter, but we had to go many miles out to get around a rock dike. We were plowing through a 4’ to 6’ chop and while it wasn’t dangerous, it was bitterly uncomfortable. I was throwing up again in my cabin, Mom was giving Dad the evil eye, and the cat had lost its grip and was tearing around below decks.

Dad had his resolute expression glued on as Mom said, “Why did we come on this trip, you…you brought us, what is wrong with you?” Suddenly, a small plane flew low on our port side and dipped its wings to us. We waved. It came by and dipped its wings again, we began to worry. We were about to pass the end of the dike, according to the chart, and eager to bring an end to the thrashing into the terrible chop, when a large boat came roaring up in sight and hailed us on the VHF. The airplane pilot, who spotted schools of fish for the fishing boats, had contacted the fishing boat to convey an important message to us: The dike had recently been extended an extra mile and the chart we had didn’t show it. Breaking waves should have given it away, but waves were cresting everywhere because of the shallow water.

We forged on until the fishing boat signaled that all was well and we finally rounded the dike. Sick, beaten, and exhausted, we entered Bayou la Loutre. The wind had fallen to a gentle 5 knots and a full moon rose above the marsh. The MARY SAVAGE ran before the breeze on gentle ripples. The terror was gone, I was recovering swiftly, and the place was beautiful. We dined on smoked oysters on top of saltines and Mom opened a bottle of wine. “All shall be well, all manner of things shall be well,” she said as she poured, quoting the 14th-century anchoress Julian of Norwich.

We anchored for the night at the easterly end of Bayou la Loutre. The next morning, we crossed back into Mississippi and anchored off Long Beach that evening. The MARY SAVAGE had accumulated a significant amount of scum on the bottom since we started our journey despite the copper bottom paint, and Dad wanted to clean the bottom and make sure everything looked sound before we continued our journey. We careened her in shallow water and waited for the tide to go out. Before long, two men were shouting to us from shore. We thought they were interested in the boat, but when Dad went to talk to them they told us we couldn’t careen our boat on the beach. They were apparently some local officials. Things got a bit heated until the man who owned the beachfront came out, told the two to leave us alone, and apologized for their rudeness.

When the tide came in we moved on and anchored off the beach in Biloxi, but soon we moved again, this time to the harbor in Ocean Springs. It was one of the nicest towns on the Gulf Coast that we went through. We stayed for two weeks there; the slips were cheap and the folks were friendly. When we left Ocean Springs we anchored off of Horn Island, a wild and deserted island with huge sand dunes and sea oats. We trekked across the island and found its marshy interior, several large lagoons teeming with birds and animals, and the deserted beach on the Gulf side. Back at the boat that afternoon I went swimming in the clear, salty water. Around evening we saw a large alligator, close to 14′ long, swim out from shore and quietly submerge. About 100 yards away, a cormorant was sitting on the water, preening; a sudden splash and the bird was no longer there. The alligator cruised back to shore; I was glad that I had not been the cormorant.

Leaving Mississippi behind, we entered Alabama. Dad’s family had a second house in Gulf Shores for years, but the place had changed drastically. The beachside condominiums were beginning to replace the old, simple beach houses. Dad was disgusted and we pressed on. We crossed into Florida and made port in the small village of Pirates Cove. Our cousins joined us again and we took several overnight trips out to the barrier islands. Uncle Buzz, my Dad’s cousin, taught me how to gig flounder and to steam oysters open on a campfire.

A few more days and nights put us in Destin, where Dad’s uncle, Paul, lived. Uncle Paul had been in the Air Corps during WWII and flown DC3s across the eastern Himalayan Mountains—The Hump—into Burma. He lived in Africa afterward selling Cessna aircraft, but that was a front for his work as a CIA agent. He had also sailed twice across the Atlantic on his 39′ sailing yacht. He and his wife, Louise, let us stay for a few days in their fancy condo on the beach. It was good to clean up and cool off, but we were terribly out of place. Destin had beautiful waters, white sand beaches, a million tourists, and endless souvenir shops. Despite the hospitality, we did not stay long.

As we moved east along the Florida Panhandle, the heat, bugs, and tight quarters were taking their toll on morale. I asked to be towed behind the MARY SAVAGE in HAPPY COCKROACH, and to my surprise there was little argument, in fact they suggested I might do it again the following day. Dad payed out the line until I was 100’ behind the boat. I was able to pretend I was in command of my own vessel, and my parents were able to talk to each other without my frequent interruptions.

They discussed the coming open-water passage around Florida’s Big Bend, the arc of coast between the Panhandle and the peninsula. Beyond Apalachicola we’d have to leave the safety of the intracoastal waterways that stretch from Texas and Maine. Dad had been hoping Mom had grown more confident in the MARY SAVAGE’s abilities and would be ready for the leap, but her terror built. This fear was reinforced one afternoon just out of East Bay in Panama City, when a sudden squall caught us. We had time to get the sails down, but very little else. For an hour, Dad stood on deck, motoring at a standstill into the storm and trying to keep the one channel marker that was visible in the rain the same distance off the starboard side. Mom was crying, the cat got on deck and bit Dad on the foot, and the wind blew his glasses away. We were in no danger of drowning—there were shallow oyster shoals on either side of the channel—but the MARY SAVAGE would have been smashed up by the high chop and nasty, sharp, oyster-shell bottom.

We arrived in Apalachicola in July of 1991. Though we stayed aboard the MARY SAVAGE in her slip at the Deep Water Marina, we began to put down roots. During the summer we kept after cabin windows open and a rigged a makeshift awning to provide some shade.

We all needed a rest. We entered the Apalachicola River the next day and sailed along until the little fishing village of Apalachicola came into view. Dropping our sails, we turned and motored up Scipio Creek. At Deep Water Marina we saw an older couple busy working on some obviously new slips. We asked if they were open for business and they said they would be glad to have us.

Harold was a retired tugboat pilot out of Long Island. He and his wife, Dee, had moved to Apalachicola and just the week before opened the marina as a second career. The rates were reasonable because they were trying to attract business. Our plan was to resupply, take on water, and refuel before we made the Big Bend jump. Apalachicola was a quaint, untouched fishing village full of eccentrics, artists, fishermen, and slowly decaying Victorian houses. The river and bay were teeming with fish, and the modern world had not yet touched the little town. Fishing boats for shrimp, grouper, mullet, and oysters were far more numerous than yachts.

During our stay in Apalachicola, Mom passed the time painting with watercolors. The owner of a local gallery took an interest in some of her artwork inspired by our voyage.

We stayed for a week that turned into a month. Mom’s paintings of boats, swamps, and wildlife she had seen along the way were very popular, and many locals hired Dad to build or do odd jobs for them. He helped Harold and Dee with the marina and then started restoring one of the local houses. Summer was swiftly becoming autumn.

The house in Apalachicola was surrounded by big live-oak trees. Mom and Dad could not resist buying it and the voyage was officially over when they did.

I was wondering if we would ever leave when a late Victorian house under two live-oak trees in the prettiest part of town came up for sale. The price was quite low, and Dad could not resist buying it. Mom was ecstatic; she loved the idea of a house with enough room for privacy in a town that time forgot. Dad sold the MARY SAVAGE to an older couple and went to work restoring the house. I went to the local school, and Mom started selling her paintings downtown.

Before long, life shifted to a new normal. Dad would soon be anxious again to build another boat, a steel-hulled stern-wheeler, and this time he would not have to travel very far to reach the sea. I would spend my teens and early 20s exploring the Apalachicola River and Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. It would be 12 years before we returned to our land in Mississippi.![]()

Nicholas Blake lives on his family land in Mississippi with his wife and two boys. When he is not playing music, he is building something in his shop or at his forge, wandering in the woods, messing about in boats, or fostering his family’s penchant for eccentricity. “From Father to Son,” his article on building a Whitehall, was published in the April 2018 issue.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.