My father passed away three years ago at the age of 91, and I certainly won’t need Father’s Day this month as a reminder to think about him. My home is filled with things that he made; the ones I value most he whittled from bits of wood.

As a young man he carved half models of sailboats he grew up with. To pass the time while he was in boot camp at the Marine Corps base on Parris Island, South Carolina, he whittled figures: a Mohican with a tomahawk, Toad from The Wind in the Willows, a Scotsman in a kilt drawing his sword. When my sisters and I were young he whittled toy boats for us; when we were older and went backpacking he carved spoons and dolphins at camp.

My father whittled this man on a stool, with a block of wood in one hand and a knife in the other, from a piece of sugar pine in the 60s.

My father passed away three years ago at the age of 91, and I certainly won’t need Father’s Day this month as a reminder to think about him. My home is filled with things that he made; the ones I value most he whittled from bits of wood.

As a young man he carved half models of sailboats he grew up with. To pass the time while he was in boot camp at the Marine Corps base on Parris Island, South Carolina, he whittled figures: a Mohican with a tomahawk, Toad from The Wind in the Willows, a Scotsman in a kilt drawing his sword. When my sisters and I were young he whittled toy boats for us; when we were older and went backpacking he carved spoons and dolphins at camp.

During one summer vacation in Marblehead, Massachusetts, he carved a nude female torso in mahogany. I was not yet 10 and didn’t think much of it until he brought the work-in-progress into the kitchen during my lunch and asked Mom to raise her arm. He studied her armpit, compared it to the carving, and after that I felt awkward about that sculpture, knowing it was my mother I was seeing.

The living room of the house I grew up in smelled like Alaska yellow cedar. My father was a crew coach for most of his adult life and he was forever whittling small oars to give as awards for his rowers. He did the work with a jackknife, a set of five small carving chisels, and small bits of sandpaper. The fragrant shavings and wood dust fell on his lap and on the large, brown, braided rug that my grandmother made. That rug was not hard to vacuum, but the grass-green shag carpet that replaced it in the ’70s didn’t give up the shavings so easily.

I don’t remember when Dad gave me my first pocketknife, but I do remember being sent to the principal’s office when I used it to sharpen a pencil in my second-grade classroom. I had to wait there for Dad to make a special trip to pick me up. When he arrived, he got an earful from the principal, Mr. Garrison, who considered the knife a weapon instead of a tool. Afterward, as we walked from the office to the car, Dad sidled up to me slipped the knife into my hand and said: “Just keep it in your pocket.”

I took to whittling when I was still quite young, and Dad let me learn about sharp blades through experience. I got my first gash, now a crescent-shaped scar across my left thumb, while I was whittling a piece of pine with an X-acto knife. I happened to be swinging on the swing set in the back yard at the time. I gave up trying to swing while using cutting tools, but I still nick myself. I was in my late 30s when a sharp carving knife split the tip of my thumb on Halloween. The trick-or-treaters, in the spirit of the night, weren’t fazed by the bloody rag I had wrapped over the wound when I came to the door with a bowl of candy.

In my 20s I took to whittling oars like Dad did. I didn’t have quite so strong a connection to crew, but I was drawn to the sculptural shape of spoon blades, particularly at the throat, where the central ridge of the blade meets the roots of the edges and the crest of the loom. Set upright in mahogany bases, the oars were, like those my father made, simple but pleasing bits of sculpture.

I remember Dad carving half models of the boats that he owned—a lapstrake Herreshoff Amphi-Craft dinghy and a Tumlaren sloop—and I followed in his footsteps carving half models of my boats. I made model boats and oars as gifts for friends and family, and took special pleasure in giving them to my father.

After he passed away, many of his carvings and all of the carvings I’d made for him came to be displayed in my home. They don’t merely remind me of him; they remind me how much I have wanted, in many ways, to be like him.![]()

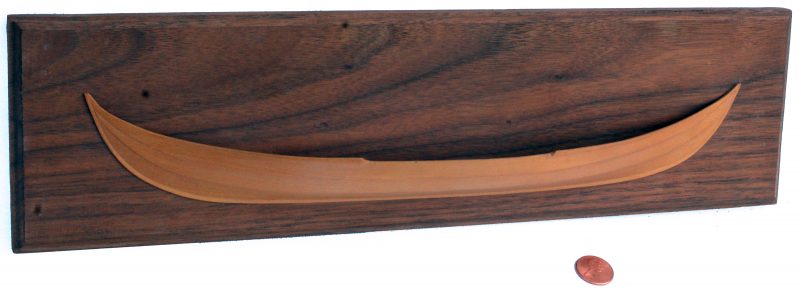

My grandfather kept MOLLY MAY at Marblehead Harbor. Dad grew up sailing her and made this half model.

Another half model carved by my father

The upright oar at the back is one Dad carved as an award. The blade is painted in the colors of Lakeside School in Seattle, my high school and where Dad was an English teacher and crew coach. The two oars in front of it are sweeps, mementos of Noble and Greenough, the Boston-area school where Dad first took up crew. The middle two oars are sculls he never finished. The two in front are fixed-thwart oars that I made.

I carved this oar last year for Sherri Cassuto, an Olympic silver medalist who had been coached by my father, as what I hoped would be a pleasant distraction while she was hospitalized.

One summer Dad carved three toy boats for my sisters and me. I got this 6″-long tender with an outboard-ready transom. All three were painted for use in the bathtub.

I don’t recall if I painted this tiny skiff or had Dad do it. I don’t think it meant that I would have rather had an aluminum toy boat.

I wasn’t allowed to play with this peapod. The hull is just a shade over 1/32″ thick and it glows when I shine a flashlight through it. Dad hollowed out the inside with just a pocket knife and while the surface has a bit of texture to it, the flashlight shows that the thickness is uniform throughout. It’s a daring piece of woodworking.

Dad would char the dolphins to smooth the knife marks and darken the wood.

Dad owned a Knud Reimers-designed Tumlaren for many years and sold it after I built a gunning dory for him. I have his half model to remember the sloop by.

When I was 12, I briefly strayed from the path.

Dad instructed his crews to “finish on a bent oar,” so I made a bent oar for him. He also discouraged his crews from spending time on an ergometer because the exercise machine fosters bad rowing habits. I made an “Ergomet-oar” for him with spinning blades that would solve the problem.

I often carved boats without any existing design in mind. I bought some crooked knives to make carving out the interior easier and cleaner.

Video by Ed and Zach Heaton

Video by Ed and Zach HeatonAs a gift to my father, I made a half model of the Gokstad faering I’d built and rowed up the Inside Passage.

After I read Paddle-to-the-Sea to my son, he wanted a canoe of his own.

To make a toy cabin cruiser for me Dad carved a plug for from a block of mahogany. To me as a young boy, it was just a means to an end. Now it’s a work of art that I keep on display in my home.

The 15″ cabin cruiser, made from the mahogany plug, has a motor powered by four C cells. It’s over a half century old and still works.

I carved this 17″ Whitehall for myself and as a plug for fiberglass copies.

After I carved the Whitehall, I did as my father did and made a mold from it. I made several ‘glass Whitehalls as bathtub toys for my kids and my sister’s kids. An outwale finished the rough upper edge of the hulls.

Wonderful recollections and photos! I am curious as to the specific tools (knives, chisels, etc.) used to create these wood carvings. Could you show pictures and perhaps identify their utility for certain carving tasks?

Dad did most of his carving with ordinary two-bladed jack knives. He liked them with antler handles. He would use a knife for years and sharpen it so often that the tip would move up along the back of the blade until it was no longer protected in the handle’s slots. He had a set of 5 1/2″ chisels with rosewood handles and used them only when his knife couldn’t do the job.

I use a wider array of tools. The knife at top is a German chisel-like knife that works well for cutting the angles at keels and lapped strakes. The rest of the knives have blades that I bought from Gregg Blomberg of Kestrel Tools. I used to live on Lopez Island in Washington’s San Juan Islands where Gregg is located and was impressed by the variety of blade shapes and how well the steel holds an edge. I made the handles for all of my Kestrel blades. The straight blade (the one that bit me on Halloween) is a good general-purpose tool. The rest of the blades are double-edged and curved.

The slightly curved blade at the top is good for fairing surfaces. The knife with the curved tip can do very heavy work and some hollowing. The fully curved blade at the bottom is meant for hollowing.

I protect the blades with sheathes. From the top: a wooden sheath, a birchbark and spruce-root sheath that I made from scavenged materials while teaching at WoodenBoat School, a rawhide sheath, and a hinged sheath carved to fit.

Occasionally small planes and spokeshaves are useful. The plane at the top is my father’s old Stanley #100 1/2.

A very nice tribute to your father. I remember scaling a 3″ plastic tugboat into an 8″ wooden tug for my first son for a Christmas present. I also learned about sharp tools the hard way, after a newly sharpened gouge skidded off the cabin face and buried in itself in the palm of my hand. Made quite a gusher.

My next project was a wooden ball in a wooden box with open sides, copying one my father did when I was a child. His was better. Thanks for the memories.

Hey Chris, very enjoyable! I’ll bet some readers are sharpening their knives. What a nice indirect portrait of your dad. Well done.

I feel my Dad’s hand guiding mine when I teach a grandchild how to tie a bowline, cinch some stock in the vice, or wrap sandpaper around a block. Mostly I remember being a trusted apprentice at 6 to 10 years old, helping him build the house where I grew up. I agree, we don’t need Fathers’ Day to light up those memories.

Brilliant insight as to how knowledge is passed from father to son. What a wonderful person to pass this to his son.

Thank you for this tribute! My tools and knowledge are also from being my father’s apprentice or light holder under a hull on a cold winters day. Every wooden craft I refinish or restore I always say, he is with me, helping finish with the help of his tools left behind.

It is such a privilege to read this. I love wooden boats, the closest I have come is assembling balsa wood kits with motors. Over two summers I also helped a group of children assemble their own boats. It remains one of my cherished memories. I come from a city that was highly regarded for its knives. Alas, most of it is gone.

New Delhi, India