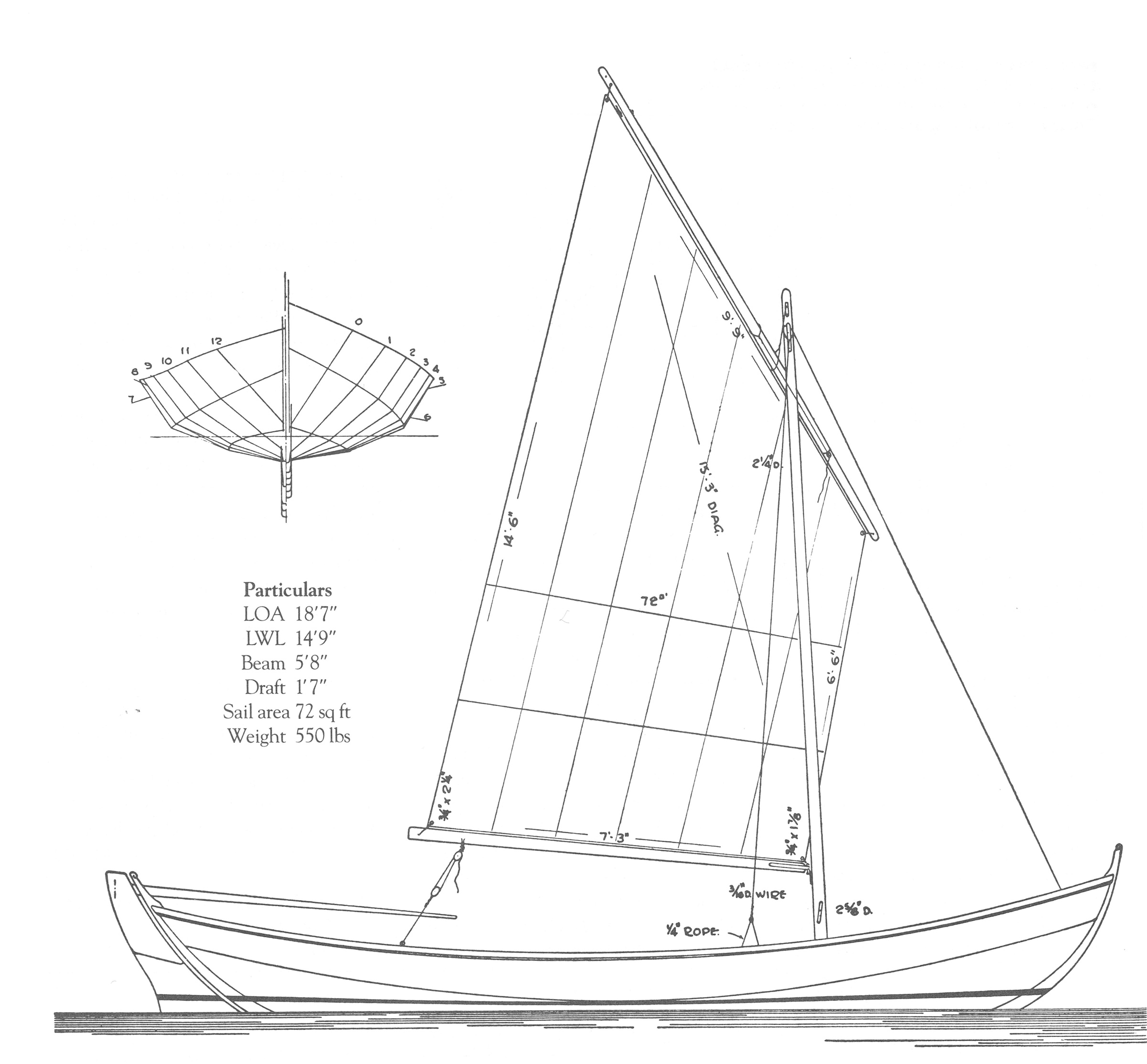

A striking double-ender, form perfected by evolution

The hull design for this handsome jekte (Norwegian for this type of boat) should be credited to generations of builders along the shores of Hardangersfjord, Norway. We’re told that these double-enders enjoy a reputation for hard work and possess rough-water capability comparable to our peapods and Sea Bright Skiffs.

One day in the early 1950s, John Atkin and his father, William, caught a quick glance of an imported Hardangersjekte resting in a lot beside a busy New York highway. The hull form, perfected by evolution, moved them. Fortunately for posterity (us), the Atkins found a sister hull, and John set about taking off its lines. (That is, he recorded measurements from the boat and used the data to draw the hull lines on paper.) Because he suspected that a transplanted jekte wouldn’t be carrying its usual cargo- a healthy catch of fish – he drew a shallow ballast keel that housed about 106 lbs of lead.

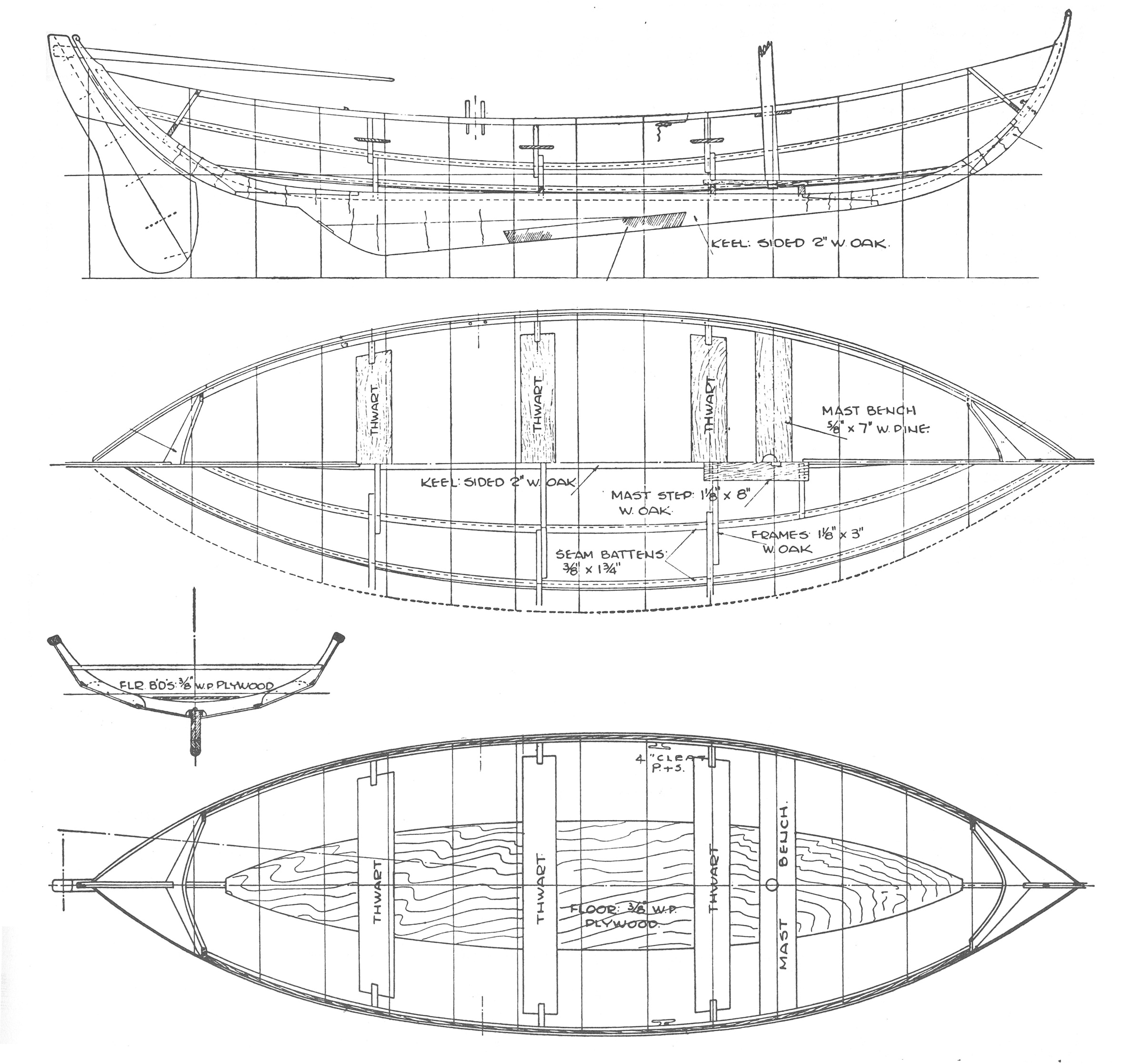

An expert Norwegian builder had planked the Hardangersjekte with lapped and riveted ½” pine strakes that measured some 18″ in width. Aware that 20″ -wide boards of any usable species would be hard to find, the Atkins specified ¼” plywood for the hull of this boat. John’s drawings indicate that lapstrake construction gave way to multiple chines.

Valgerda forsakes the wide pine planks of her predecessors for high-quality plywood. Construction remains clean and open.

Because we now have access to epoxy, you might consider building Valgerda using the glued-lapstrake plywood method favored by Joel White for his Nutshell prams and their cousins (see WoodenBoat No. 60, page 100). This technique is faster than battened multi-chine construction in the hands of most builders, and it can produce a slightly lighter boat with a cleaner interior. Shadow lines cast by the laps will accentuate the hull’s shape, as they must have in the original Hardangersjekte.

Although similar boats had been fitted with tall, sloop rigs for racing and daysailing in their native waters, the Atkins gave Valgerda a solitary standing lugsail. William applauded the chosen rig as being “a most practical one for for hard use and thin pocketbooks; to say nothing of long life.”

In the interest of control and simplicity, you could replace the standing lugsail with a balanced lug. The modest ability of the latter to reduce sail twist might be appreciated in a boat with so narrow a sheeting base, and the gooseneck fitting would be eliminated. A slightly more robust mast and partner would permit dispensing with all standing rigging – at the cost of some what greater weight.

A long time ago, I had the pleasure of rowing a boat built to these plans. Strong effort was required to get her moving, but she consumed little power underway. Between strokes, Valgerda’s considerable momentum could have carried her into the middle of next week. She loved rough water and had sense enough to mush through the small waves and ride over the big ones. Rowing this boat was pure joyor would have been if the builder hadn’t installed a centerboard trunk.

-M.O’B.

Plans from Atkin & Company, Box 3005,

Naroton, CT06820.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.