Sam Devlin’s boat designs always major in strength, practicality, and versatility. But Sam is an artist, a complicated, self-contradicting, cigar-smoking romantic, and frequently he can’t help himself: He draws a boat that’s as unapologetically cute as it is strong. This describes the Winter Wren, one of his older designs (the earliest example dates from 1980), and the one that lured me down a life-changing path a decade back.

I had already built a smaller and simpler Devlin boat, the 13′6″ Zephyr daysailer, a project that seemed plenty challenging at the time. The Winter Wren, while employing the same stitch-and-glue composite construction that I’d begun to get comfortable with, added the complications of cabin, outboard motor, electrical system, much more structure, and vastly more rigging. Listen, this rig is stout. One day I was scrutinizing a 24′ production sloop whose owner was embarking on a bluewater cruise to Hawaii, and I noted that the much smaller Winter Wren’s standing rigging was far more robust. This gave me a warm feeling.

Lawrence W. Cheek

Lawrence W. CheekThe Winter Wren II will take an outboard between 2 and 4 hp. The transom motor-mount cutout—the author’s design and not in the plans—does allow about 15 degrees some swiveling in each direction, which is used in concert with the rudder for maneuvering inside marinas.

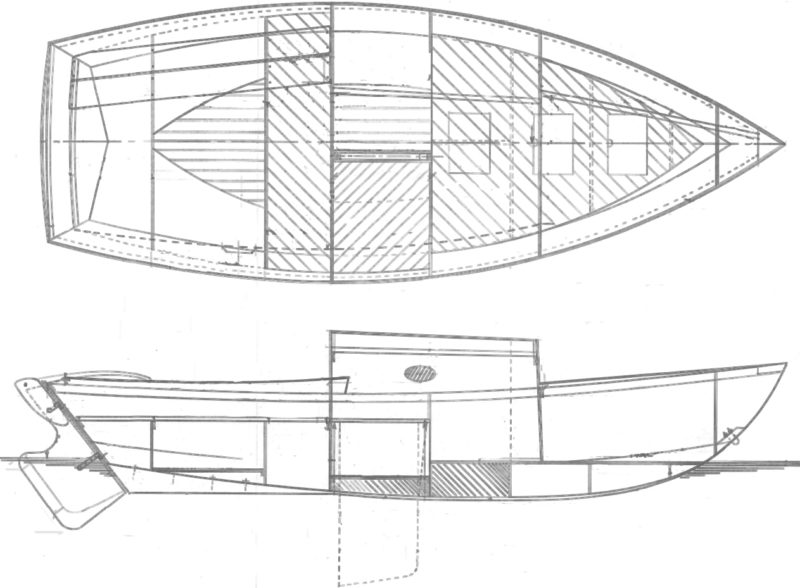

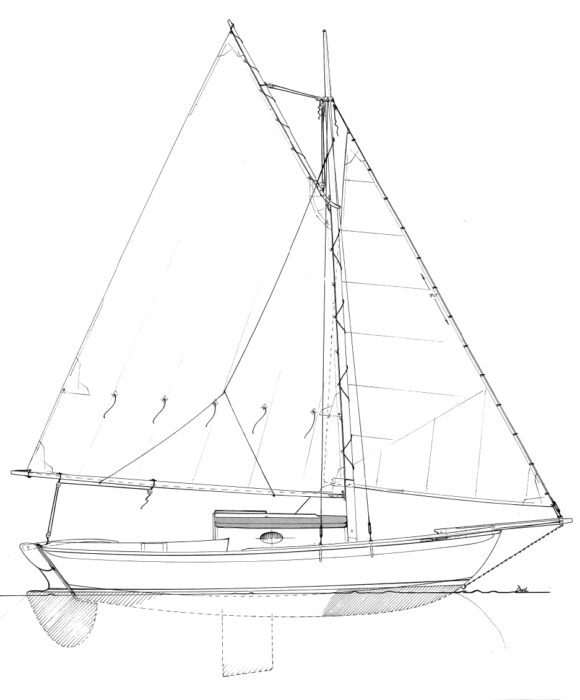

The original Winter Wren, still available in Devlin’s plans catalog, is a full-keel gaff-rigger measuring 18′8″ on deck, 22′7″ overall, with a 6’10″ beam. The Winter Wren II wears the same dimensions except for a 7′ beam, and it substitutes a daggerboard for the full keel. Both versions weigh about 1,800 lbs and carry 685 lbs of lead ballast, all lodged internally. Plans for the latter include both marconi and gaff sail plans, either measuring 176 sq ft. I chose to build the gaff daggerboard Winter Wren II with visions of trailer excursions to sailing destinations around the Pacific Northwest. I now know that was unrealistic. The Winter Wren II is too big and complicated to serve routinely as a trailer-sailer: it takes me 2 hours to wrangle the rig up or down; plus, I’ve learned that I hate trailering. If I had it to do over, I’d opt for the full-keel outfit, which is stiffer under sail and enjoys more unencumbered cabin space.

Although it’s one of Devlin’s older, hand-drawn designs, the Winter Wren II is now available as a CNC-cut hull kit. If you build from scratch you’ll have to scarf plywood sheets, loft the hull panels, and craft your own building jig. While some of this is fun, a kit offers advantages in precision and saves considerable time. Either way, this design teeters on the cusp of being a reasonable first build for the amateur: maybe so for someone with substantial woodworking and some sailing experience; probably not for the woodshop rookie. I had built a pair of kayaks and the Zephyr daysailer, so I was moderately confident starting out—and I still came to spend many nights awake at 2 a.m., questioning my judgment and competence. In an effort to drown the doubts, midway through construction I named the boat NIL DESPERANDUM, “Nothing to Worry About.” It did not help.

Dennis Ryerson

Dennis RyersonThe Winter Wren II’s sail area of 176 sq ft is good for light summer breezes, and the entirely feasible addition of a topsail would make it even better.

I made a couple of changes in the design—one practical, one aesthetic. I sacrificed some storage to build in 14 cu ft of positive flotation, equaling about 900 lbs of saltwater. I’ve never even approached capsize, but in a worst-case scenario, I’m confident NIL DESPERANDUM would stay afloat. I also wanted to invite more daylight inside, so I built competing cabin side mockups with Devlin’s one and my two portlights and photographed each on the boat. I emailed the photos to eleven friends, all either sailors or architects. Eight voted for the two-light version, so I felt I had authorization, though I didn’t ask Sam.

The plans don’t call for a ceiling (a wooden liner around the inner hull), but I felt it would make the cabin visually warmer, so I built one of 1/8”-thick vertical-grain fir planks screwed to battens epoxied to the hull. It was worth the effort. Even with just 43″ maximum sitting headroom, the cabin is a pleasant place to hang out. The Winter Wren II’s main drawback as a minimalist cruiser is that storage space is likewise minimal. On the several multi-day cruises I’ve taken with my wife or a friend, we’ve stashed our accumulations on the V-berth during the day but had to shuttle some of them out to the cockpit when sleeping time arrived. Even if deploying sail covers over the banished goods, this tends to be a soggy solution.

Lawrence W. Cheek

Lawrence W. CheekEverything falls easily to hand in the cockpit for singlehanding: all lines, the tiller, and motor controls. A folding plywood boarding ladder stashes under the starboard coaming and side deck.

The most difficult aspects of the construction, looking back, were the hull fairing after the ’glassing—long, tedious, and ultimately imperfect; I have since discovered the blessings of System Three’s Quikfair—and the rigging. I had no experience with rigging, and I was determined to bring all sail control lines into the cockpit, which added complication. I took camera and notebook to marinas in Seattle and Port Townsend, haunted the docks, and studied. Helpful reassurance came from a friend who’s a retired professor of physics and a sailor. “The loads on a rig like the Winter Wren’s are so small that almost anything you do will work,” he said. He was right.

The Winter Wren II splits accommodation space between cabin and cockpit perfectly. The 6′6″ cockpit seats welcome four adults for daysailing, and are tolerable for sleeping if you carry a boom tent (we’ve accomplished two-day cruises with three aboard). There’s a bridge deck 16” deep with storage underneath for a porta-potty and quick-access miscellany such as tools and first-aid kit. The footwell is too deep for self-draining, so an automatic bilge pump or a cockpit cover is essential. My only ergonomic criticism is that the cockpit is slightly too wide for comfortable tiller management; a short-armed helmsperson can’t quite lounge back on the coaming and hold the tiller on center. Curving the aft side decks in 2″ more would solve the problem.

Summer sailing in Puget Sound asks for boats that are satisfying in light air, and the Winter Wren complies. It starts sailing with 3 knots of poke, feels alive in 5, and can make her official hull speed of 5.3 knots on a close reach with about 8 knots of breeze. I reef at around 10 knots of wind when the boat is beginning to feel a bit harried. I have a second row of reefpoints on the mainsail but no longer use them; the Winter Wren doesn’t seem to like a double-reefed main. What works best is to take the first reef at 10, roll up the jib at 15, and start heading for home if it seems likely to rise much further.

Lawrence W. Cheek

Lawrence W. CheekThe Winter Wren’s cabin acreage is mostly given to the V-berth, which is punctuated with the mast compression post, a 1″ steel tube dressed up with a mahogany sheath. The daggerboard case, slightly offset to starboard, bisects the rest of the available space.

Like any self-respecting gaffer, the Winter Wren II resists being ordered tight to the wind, like a distinguished dinner guest being asked to do the dishes. It tacks in 100 degrees and makes rather gradual progress if you have an actual destination from which the wind is huffing directly at your nose. One strategy in such cases is to fire up the outboard—I have a 4-horse four-stroke, which is adequate—and run it quietly just above idle, which will tighten up the close-haul vector by 4 or 5 degrees. In compensation for its windward reluctance, the rig is an efficient delight on a broad or beam reach, or even a downwind run. In light air, I love to clip a preventer line to the boom and sit out front on the cabin roof, poling out the jib with the boathook for a wing-and-wing configuration. It’s so peaceful out there.

The great joy of the Winter Wren is its responsiveness. Every nuance of change in air or water conditions translates into some sensation transmitted directly through the tiller, sail controls, or seat of pants. There are no filtering mechanisms such as winches between controls and fingers, so every input has a tangible effect that you not only see but also feel. Tiller touch is light; when you find the groove there’s barely a fingertip’s worth of weather helm. You’ll frequently choreograph the crew to change sides, sometimes during a tack, and tinker constantly with the mainsail shape by playing the peak halyard, outhaul, and mainsheet. For me, this is what sailing is about: savoring the multi-sensory array of interactions between natural environment and machine, and learning to gracefully negotiate among them. On days when conditions are reasonable for small boats, the Winter Wren feels like an extension of your body, an organic being in itself.

Dennis Ryerson

Dennis RyersonThe rig has its complications—four halyards and five stays—but the 20′ mast pivots on a bolt in a tall and beefy tabernacle, which makes it reasonably easy to raise and lower. NIL DESPERANDUM’s solid spruce mast weighs 40 pounds, but hollow birdsmouth construction would save about 15 pounds.

Devlin’s shop will cheerfully build you a Wren if you ask. I have a copy of the January 1984 Small Boat Journal in which a Devlin-built Winter Wren was the cover story, and it then carried a base price of $10,980. I hardly have to add that today’s bill would be several times that, which is why few pocket cruisers are being professionally custom-built now. I spent about $20,000 for parts and materials to build NIL DESPERANDUM in 3,000 hours over three years from 2008 to 2011, including motor, sails, covers, and cabin cushions. In heartless economic terms, that makes no sense—I could have bought a used production pocket cruiser in good condition for half that.

Some paragraphs ago I wrote that NIL DESPERANDUM had lured me into a life change. I have built two boats since, one smaller, one larger, and I am now more boatbuilder than writer, my previous lifelong profession. This is my career now, regardless of the fact that it consumes income rather than generating it. But building boats, like owning them, is never about heartless economy.![]()

Lawrence W. Cheek is a journalist, frequent contributor to WoodenBoat magazine, and serial boatbuilder. He lives on Whidbey Island, Washington, and since 2002 he has built two kayaks, three sailboats, and currently is at work on a fourth: 21′3″ Song Wren, a Sam Devlin–designed gaff cutter.

Winter Wren II Particulars

[table]

Length on deck/18′8″

LOA/22′7″

Beam/7′1″

Draft, board up/1′1″

Draft, board down/3′6″

Outboard power/2 to 4 hp

Displacement/1800lbs

Sail area/176 sq ft

Maximum load/1250 lbs

[/table]

Plans for the Winter Wren II are available from Devlin Designing Boat Builders for $162 (print) or $132 (download). Study plans are $1.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I’ve always felt that Sam Devlin does for plywood what L. Francis Herreshoff did for plank-on-frame. Practical, useful, designs that manage to be beautiful.

Great article and boat. Sam Devlin has certainly found a niche in building so many different designs in plywood.

Wonderful article, Larry!

I really enjoyed your article. I had to laugh as I read your last paragraph. I read it to my wife and she grinned, knowing the money I have poured into boats over the years!