A couple of years ago I spotted a long, lean traditional Finnish rowing boat for sale online. It had been designed and built for bi-stroke racing with a rower on a sliding seat and a paddler using a single-bladed paddle in the stern. I had no experience in competitive rowing or even cruising under oars, but I fell in love with the boat and bought it. Its lines promised good speed and tracking, but it had been neglected and had some broken frames and split planks. During the following winter I restored it and added a second sliding seat for doubles rowing. We launched the boat in the spring, and call it TURBO.

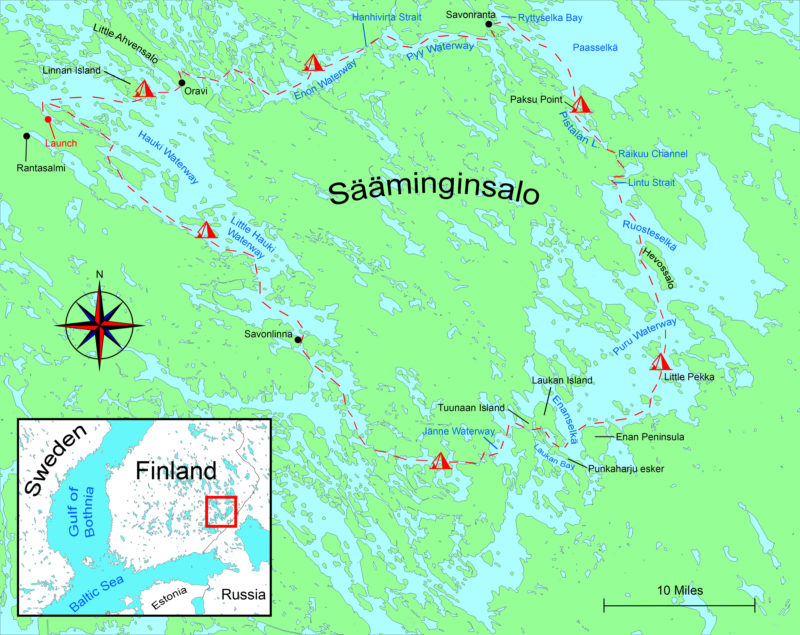

Finland is dotted and laced with thousands of lakes and waterways. The Saimaa area in the southeast is the country’s largest watershed with 9,300 miles of shoreline, more per square mile than anywhere else in the world. The 14,000 islands in the region add to the complexity of Finland’s vast Lakeland. In the past, rowing was the fastest way to get around Saimaa and many other watery inland parts of the country, and rowboats were essential to the traditional ways of life. Each region has its own native boat designs, with characteristics that have evolved over hundreds of years to suit local tastes and conditions. I had been spending my summers sailing all around the Baltic Sea and staying with my family in our summer place in the archipelago along the south coast, so the inland waterways and lakes weren’t familiar to me; I’d only seen them from a car window or through some occasional visits to friends or relatives with summer cottages. Now that I had a boat descended from Finland’s rich inland traditions, it was time to explore Saimaa.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

For my first trip, a 111-mile circumnavigation of Sääminginsalo Island, the largest island in Finland, my oldest son, 14-year-old Verneri, would be the one pulling the second pair of oars. He is an outdoorsy person with a great interest in nature, animals, trekking, camping, and just about anything that requires a good deal of physical effort.

With the car loaded with camping gear and food we drove to Rantasalmi, a small town near the northwest part of Saimaa. As we were loading gear into the boat at the top of the launch ramp, I began to feel a bit anxious. How would this racing boat handle all this extra weight in waves and wind? Would Verneri and I really be able to row the 20 to 30 miles we’d planned for each day of the week we had allowed for the trip? The sun was shining and the wind was light and the fine weather soon put me at ease. We loaded up and organized all of the gear in the boat—food box, cooking equipment, camping gear, clothes packed in watertight bags—and still had enough room around the sliding seats for rowing. We took off and once we settled into our rhythm, TURBO was like a train, running fast and true, as she charged across the half-mile-wide bay toward more open water.

As we crossed the Hauki Waterway, a 30-mile-long, 5-mile-wide lake in Saimaa’s network, most of my worries about the boat and our ability to row it well were vanishing. I didn’t find it too difficult to read the compass or to glance at the map while I was rowing. With fresh reserves of energy and the wind behind us, Verneri and I managed to keep speeds between 5 and 5.5 knots and were thrilled about how well the boat was performing. We glided beneath blue skies as nearby islets capped with dense green forests of pine and birch slipped between us and distant islands dotting the horizon.

As sailors, Verneri and I weren’t used to having our backs to the bow, and I paid more attention to the compass and the map than to what was ahead of us. After we almost ran straight into the rocky shore of a tiny island at full speed, we made more frequent glances forward while rowing. We worked more carefully through the Hauki archipelago and landed on an island no larger than a tennis court. With TURBO in still water, nosed up against the lichen-dappled granite shore, we took our first break, ate some sandwiches, and took a dip in the clear and, to Finnish standards, warm water.

all photographs by the author

all photographs by the authorThe calm waters and mild weather at the start of the tour were perfect for rowing. A light tailwind helped for a while but died completely during the crossing of the Hauki Waterway. The compass, meant for forward-facing kayakers, had to be installed backwards for the rower in the bow rower to see the card, and that required some mental gymnastics to set a course. Rowing here on a course of 105°, ESE, the compass reads 285°, WNW.

About 7 miles out from the launch site near Rantasalmi, we passed Linnan Island, a national park almost in the middle of Hauki. The island, 2 ½ miles long and a mile wide, is covered by forest right up to the water’s edge, save for a couple of clearings for campsites. (The park gets visitors year-round; in winter visitors arrive not on boats, but on ice skates.) We rowed around the south end and chose a smaller island close by for our first night. It was shielded by Linnan to the north and by a pair of half-mile-long islands neighboring south and east, but the wind had died, and mosquitoes found us while we were preparing a meal. Before calling it a day we took a stroll around our little island, which was still big enough to have a dense forest and plenty more mosquitoes. We took our time exploring—the summer sun wouldn’t set until well past 10 pm—and when we retreated to our tents they were still warmed and illuminated by the slanting daylight.

Beyond the bridge that spans the canal at Oravi is a quiet village that occupies the site of a busy ironworks that closed in 1901.

The following day we had only a few miles to row before entering the narrow, tree-lined channel that separates the islands of Little Ahvensalo and Sääminginsalo. Beyond the arched bridge that spans the 20-yard-wide waterway, the village of Oravi lines both sides of the channel with colorful wooden houses, gardens, and gently sloping, rocky banks. We craned our necks, keeping a sharp lookout ahead as we approached the docks on the north side of the channel. Oravi has a small restaurant and a shop, so we picked up some additional supplies and had coffee with some treats.

Refreshed, we continued north to the end of the mile-long channel, rounded the narrow peninsula that is Sääminginsalo’s northwest corner, and then rowed an eastward-winding route through a group of islands to the Enon Waterway. After we reached its more open waters we had the wind behind us, so we decided to try our jury-rigged sail. We had outfitted TURBO with a pivoting A-frame mast, which folds forward and rests out of the way along the inwales when not in use. Pulling a rope that becomes the backstay raises the rig, and the sail, a parachute-cloth hammock, follows. Its 32-sq-ft pushed our sleek TURBO along the Enon at 3 knots in the light 9-knot wind.

Sailing was a welcome break for rowing and kept TURBO moving while the crew relaxed. The A-frame mast didn’t interfere with the forward rowing station and it took just seconds to raise or lower the sail.

Verneri and I made ourselves comfortable in the bottom of the boat with our backs resting on the footrests, both of us happy to be facing forward for a change. I used the aft pair of oars as rudders. The tholes run through holes in cleats fixed to the looms, so the blades can’t be feathered and are always vertical, ideal for steering. To turn I dropped one of the oars’ blades in the water, and TURBO would veer to that side.

Sailing east across the 7-mile-long lake with nothing in sight but water, rocks, forests and sky, it was easy to imagine we were like Vikings, searching for new lands and escapades. I mentioned to Verneri that the Vikings had found their way through the rivers of Russia and the Black Sea all the way to Istanbul. He replied, “We should go too.” I could tell he wasn’t kidding.

Toward the end of the day the wind waned and we pulled out the oars. We rowed north from the middle of the lake, looking for a place to spend the night. We found a small island, only 30 yards wide and about 40 yards long, and well suited for camping. Its center was flat and free from bushes; old crooked pine trees were rooted in the thin layers of soil nestled between outcroppings of bedrock around the clearing. We had views of the lake in every direction, and best of all, the island was free of mosquitoes. There was a previously used stone fire ring, so Verneri gathered fallen branches for a fire. Before turning our attention to dinner, we took a swim and then let the sun dry us as we rested by the island’s smooth and warm granite flanks. We gazed north to the mainland, a landscape unmarred by houses or any other signs of people.

This tiny island located in the Pyy Waterway was a ideal for camping with its unobstructed views all around, clear, flat ground for tents, and absence of mosquitos.

I had forgotten to pack our fishing rod, but we had bought some fishing line and a spoon lure in Oravi. Verneri fished by flinging the lure into the water. After a few tries he shouted, “I got something!” He pulled the line in carefully and a 16″ pike came to the surface, but as it approached the shore it thrashed, pulling itself free from the lure and escaping into the lake. Encouraged, we kept fishing, but there were no more bites. We retreated to camp, dug into our food box, and had smoked lamb with potatoes for supper.

Verneri fished without a rod by slinging the lure in to the lake. At 62° North, the summer days were long and provided plenty of time for fishing after coming ashore.

The following morning it started raining soon after breakfast but we managed to pack most of our gear before it got wet. There was little or no wind and the temperatures were mild, so it was a good day for rowing. We headed east and passed through the Straits of Hanhivirta where a small ferry crosses the 300-yard-wide passage between the Enon and Pyy waterways. The landscape was getting more rugged as we traveled east and many of the steep shorelines were guarded by jagged boulders.

After rowing for about three hours in the rain, we were hungry, tired, and wet. We decided to make a detour to the north to the town of Savonranta, in the hopes of finding a place to have a hot lunch indoors. The zigzagging, mile-long entrance into the harbor seemed to go on forever, but right next to the harbor was a restaurant with pizza-buffet lunch. Verneri gorged himself on slice after slice; I counted and he stopped when he had eaten what amounted two whole pizzas. I had a lighter lunch—salmon soup.

With full stomachs and dry clothes we set out again and headed east, passed under a bridge, and entered Ryttyselkä Bay. Feeling a little drowsy after all the food, we each took turns rowing while the other trolled for fish at the stern. After clearing the bay, we were entering the most open crossing of our tour, Paasselkä, which is Finnish for Stone Lake. The 6- by 7-mile oval lake is uniquely free of islands. While all of the other lakes in the Saimaa were gouged by Ice Age glaciers, forming relatively shallow furrows aligned along a diagonal from northwest to southeast, Paasselkä is a deep impact crater formed by a meteorite about 231 million years ago. This origin of the lake was confirmed by a deep drilling of the surrounding rock in 1999, and beyond its unusual shape and magnetic anomalies, the locals had a sense that this basin was different. Light phenomena over the lake has been reported for centuries—known as “Paasselkä devils”—shining spheres thought to be created by evil beings.

The devils let us be and Paasselkä was a benign, flat calm. According to weather forecast, there were no winds in the offing, so we took a course—southeast, then veering south—well clear of the rocky western shore.

We were headed for Pistalan, a 3-1/2-mile-long lake, and then Raikuu channel, a series of three small canals connecting the small lakes in between them. We rowed into Pistalan and saw a long and narrow promontory to port and a sandy beach to starboard. There was something tempting about the beach and the headland rising above it, so we rowed our bow into the sand and went for a walk. After walking a few yards up the steep ledge we could see the headland was a maze of eroded trenches, dug in the early 1940s by Finnish civilians during the creation of the Salpa Line, a 750-mile line of bunkers running the entire length of Finland’s border with Russia. The line never saw military action—the Soviet offensive ended when the advancing Red Army was stopped in 1944 at the Viipuri-Kuparsaari-Taipale (VKT) Line before reaching the Salpa Line. The sight of the moss-covered zigzagging pathways and trenches made me think about the sacrifices my grandparents had made during the Winter War.

These eroded trenches by Pistilan Lake were a part of the Salpa Line defenses built against the Soviet threat in the early 1940s. The line never saw military action, but was nonetheless a haunting reminder of the battles fought farther east.

Day was slipping into evening as we rowed across to Paksu Point, where we found a fire pit and wooden lean-to built for visitors. The land was sandy and flat, with many good places for tents. We foraged some boletus mushrooms, grilled them with sausages for dinner, and soon turned in for the night.

The next morning Verneri told me that he had woken up in the middle of night to throw up. The mushrooms hadn’t been good to him but he did feel he was now ready to row. We packed the boat and headed southeast along the length of Lake Pistalan, which was getting narrower toward its southern end. We were expecting to see the entrance to the Raikuu channel, but there was no way out of the lake through the dense bed of reeds filling its southern bay. Trusting in the map instead of what we could see, we rowed straight into the rushes and eventually came to a small bridge. The passageway beneath it was only about 3 yards wide, and the water in the channel beyond it was just a few feet deep. The Raikuu canal, dug around 1750 and now little more than a ditch, along with the Pistalana canal and the Nurmitaipale canal and the Raikuu canal—collectively called the Raikuu channel—are all that qualify Sääminginsalo as Finland’s largest island. A mere 500 yards of narrow canal allow water to encompass Sääminginsalo, which is arguably a 413-square-mile peninsula.

It took a leap of faith to plunge into the dense reeds choking the bay that concealed the entrance to Raikuu channel. The slender manmade waterway separates Sääminginsalo Island from mainland and makes a full circumnavigation of the island possible.

Verneri and I stood up, each paddling with a single oar, to better see and follow a meandering route through small ponds and channels. The western shoreline we passed was part of the Salpa Line fortification—granite ramparts rose straight out of the water. Overgrown with birch trees, bushes, and flowers, these remnants of war are being swallowed up by nature.

Standing up to paddle Raikuu channel made it possible to face forward and enjoy the views of the most scenic part of the trip.

The end of the chain of narrow canals and small ponds ended at a bridge and boat ramp at Lintusalmi. We stopped at the concession stand there for a snack and a coffee to gather our strength for the wide waters of Ruosteselkä Bay. We rowed under the bridge and straight into a 10–12-knot headwind.

The waves surging into the bay were building up, and we had to do some serious pulling to keep TURBO moving. Eventually we reached the lee of Hevossalo Island and took refuge in a small breakwater-protected harbor located between the channel separating Sääminginsalo and Hevossalo islands. As we cooked a hot lunch, the wind and waves calmed down a bit, and with our energy restored, we continued south into Puru Waters, a large lake to the southeast of Sääminginsalo. It was still an upwind battle, but TURBO made good speed, and as the afternoon was turning into evening, we landed at Pieni-Pekka after covering 12 miles since leaving the sheltered waters at Lintu Strait. The island was small, only 50 by 100 yards, and on its northern shore there was a gently sloping rock surface that looked just like a boat ramp. We rested TURBO’s bow on the rock, found a fire ring close by, and rested our backs lying on mattresses over the flat expanse of stone. This eastern part of our circumnavigation was more rugged and solitary than the western parts of the northern Saimaa waters, and was more to my taste.

After a 12-mile upwind battle to reach the island of Pikku-Pekka even solid granite offered a welcome measure of comfort.

I was too tired to scout the islet for a better place to camp, so I popped the tent up on sloped stone. Verneri found a softer spot higher up. After our evening meal we turned in and fell asleep to the sound of heavy rain beating on our tents.

I woke up early, having slept exceptionally well in spite of the rain and my hard, slanted perch on the bare rock. The wind was coming from the southwest at 15 knots and gusting to 20. We set out, taking the wind on the nose, and worked our way into the lee of the islands to south of us, and then crawled westward and into the shelter of northwest corner of the Enan peninsula. We peeked into the unprotected waters of Enanselkä to evaluate the wind and wave conditions. This 1 ½-mile crossing would be the challenge of the day. I decided that it was a go, so we started rowing as fast as we could in the rough conditions. TURBO rolled but rode up and over the waves nicely, only occasionally letting some spray get to us. It was difficult to avoid slamming our oars into the wave crests between strokes, but after about 15 minutes the worst of it was over, and we reached the western and more sheltered part of Enanselkä. Verneri had faced the challenge head-on and fearlessly. The harder it got, the more he seemed to enjoy it.

We took a shortcut through Laukan Bay, a small pond isolated from the surrounding waters by the Punkaharju Esker and the roads running along that ribbon of land. We ducked through two small tunnels and out into the bay. A thunderstorm passed over and heavy rain thoroughly drenched us. Weary, cold, soaked, and hungry, we turned north and rowed into Tuunaan Island harbor. After a satisfying lunch in the restaurant at the water’s edge, we got to a sauna to warm up and dried our soaked clothes.

After our sauna it was already early evening, but we wanted to find a more solitary place to stay for the night, so we launched again and rowed southwest. While rowing across the 1-1/2 mile-wide waters of the Jänne Waterway, we saw a huge dark gray cloud front approaching us, and it was obvious we would be soaked again. Verneri was rowing in the aft station, and as he looked over his shoulder at the approaching storm, I noticed he was smiling. “What’s up?” I asked. “Everything is going so well! We even had a sauna,” he said. What a wonderful companion. The rain came on hard and fast and set the surface of the water dancing. Pulling through the downpour we found a small, densely grown island to camp on, just a few hundred yards off our route.

Getting soaked once more by a thunderstorm, just after drying our gear in the sauna on Tuunaan Island, Verneri didn’t mind any of the challenges of the tour but seemed the enjoy them all the more when the going got tough.

The next day the skies had cleared and the sun warmed us as we began the day’s rowing. Not long after leaving camp, a black head the size of a football popped out of the water about 50 yards behind us. It was a rare Saimaa ringed seal. With a total population of only about 310 individuals, it is one of the most endangered species of seals in the world. Trapped inland by the rising of the land following the Ice Age, the Saimaa ringed seals are one of only three species of freshwater seals. The seal followed us for 10 minutes, popping up every now and then, each time closer to us.

This was the first really warm and sunny day of our tour, and we had grown so accustomed to rowing in rainy and cloudy conditions that we forgot to put sunscreen on—an oversight we would later regret. After 11 miles of rowing in a generally northerly direction through tightly packed clusters of islands, we reached the small city of Savonlinna. For lunch we were intent on finding a certain restaurant by the market, famous for its vendace, a freshwater whitefish found locally. The meal lived up to its reputation and was the best fish I had ever had, fried crispy in butter and served with a special dipping sauce. Verneri and I were in no hurry to continue, so we strolled across a floating walkway to Olaf Castle and took a tour of the 15th-century fortress with three tall round towers and ramparts that rise right out of Savonlinna’s bay.

We got back aboard TURBO, left the town behind us, and headed north. The weather forecast for the next day was for stronger winds, so I wanted to find a place for the night where we could continue our journey sheltered from the coming southeasterly wind. We found a tiny island only 20 yards wide, close by the eastern shoreline of Little Hauki Waterway, the southern extremity of the waters we had crossed at the beginning of our tour. The evening was peaceful and beautiful; the low, shining sun made rocks, bushes, and flowers glow in a coppery tone. We sat on a cliff, looking at the western sky across another of the many beautiful waterways of Saimaa.

As forecast, the wind had increased by morning and was blowing 14 knots from southeast. Our route was perfect, though, heading northwest, with some sheltering islands east of us. We started rowing, but with the following wind and waves coming from an angle that kept pushing the stern to port, we were continually pulling only the starboard oars. We stopped fighting it and hoisted our sail. We sped through narrow channels and past summer cottages where people might have been wondering about our hammock sail and the speed it produced. TURBO was exceeding 5 knots from time to time. The rig was working perfectly. The center of effort was low, and on a broad reach or a run, the boat was not heeling at all, but charging effortlessly through the water.

After sailing for two hours we reached the bay leading back to our starting point. We rounded the point, took the sail down, and started rowing to the southwest with the wind to our port side. The wind had increased to 20 knots, and the last half mile was hard work. When we finally reached the harbor and ramp, it started raining and the wind seemed to increase even more. We had finished just in time. We unpacked the boat and trailered TURBO. We had conquered small part of Saimaa, and there were 9,200 more miles of coastline to explore.![]()

Mats Vuorenjuuri is the father of three and an entrepreneur, making a living in graphic design, photography, and freelance writing. He has sailed all his life, and wooden boats, sailing, and boating are his passions. He has restored both sailboats and motorboats, and in recent years has discovered the simplicity and joy of small boats. He currently owns a small, open plywood motorboat, a Herreshoff Coquina, and TURBO. He wrote about cruising the Finnish coast in his Coquina in our May 2016 issue.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Excellent father and son adventure

Great trip and good story! Thanks for taking the time to tell it, Mats.

Wow, what wonderful writing, you have a way of putting the reader right there in your boat. I enjoyed every word of it. Terrific pictures, too. I noted that your son had a thick book with him to read. How nice to see that. He seems to be all a man could hope for in a son. God bless you both.

Thank you for telling your story. It has inspired me to build the small boat I have been dreaming of for the past few years and to share some adventures with my sons.

Thank you for the comments and taking the time to read the story. Small-boat cruising can be really rewarding.

Small boat adventure story-telling at its best. And the young man you’ve raised is quite the able seaman already.