When I moved to the Belfast area of Maine in 1989, I brought with me ACE, a 14′ sailboat that I had built in North Carolina. She had a light, planing hull, and with a crew of two or three she was fast in a good breeze. I had had a lot of fun with her. Getting very wet in the process was no imposition in warm Southern waters.

The water in Maine’s Penobscot Bay is not warm, but after the sultry calms of the Carolinas, the brisk summer winds promised good sailing. My wife is a somewhat reluctant sailor, so I had rigged my boat with a trapeze and long tiller extensions for solo sailing. While I was on the trapeze, with two sheets in one hand and a tiller extension in the other, ACE was something of a handful, but in the right breeze she would take off like a scalded cat. Sometimes I would out-pace powerboats across the upper reach of the bay in the triangle of water north of Isleboro, between Belfast, Castine, and Searsport.

The wind had to be just right, though, for those exhilarating rides. Too little wind and the boat might zip along with a humming daggerboard and a flat, fizzy wake, but wouldn’t quite reach the frantic pace that, once experienced, made anything pale in comparison. About 15 knots of wind was ideal. Much more than that—well, that is what this story is about.

I had taken to sailing out of Searsport to avoid the beat up or down Belfast Harbor. One late spring morning, with a brisk northwesterly promising a thrilling sail, I hitched the boat trailer to my old Plymouth, and headed north along Route 1. On the drive to the launching ramp I passed flags crackling in the breeze and looking out over the bay I saw a carpet of whitecaps. Maybe I should tuck in a reef before heading out, I thought.

I’d had the good sense to invest in a wet suit soon after discovering just how cold the bay could be. Icy spray on a warm day was one thing, but the uncontrollable shivering that followed full immersion for more than a few minutes provided a salutary warning of the dangers of hypothermia. I rigged the boat, pulled the wetsuit on, and looked out from the launching ramp. The wind was blowing directly offshore, and the water’s edge was calm, only ruffled by the wind, but the whitecaps farther out were plain to see. I should reef, I thought again, but what if I could handle a full mainsail? If I could keep the boat on her feet, she might take off as never before. The temptation was too much, and with my mouth somewhat dry, I pushed off, and hopped aboard.

Arch Davis

Arch Davis“Gust after gust found her heeled way too far with me hanging on by the skin of my teeth.”

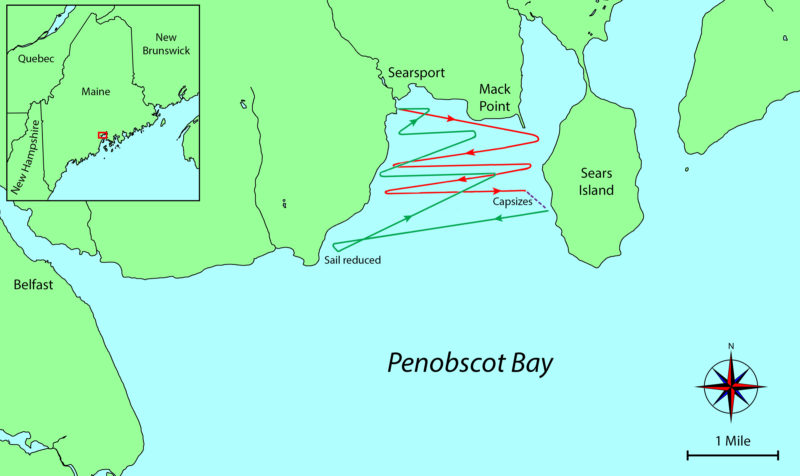

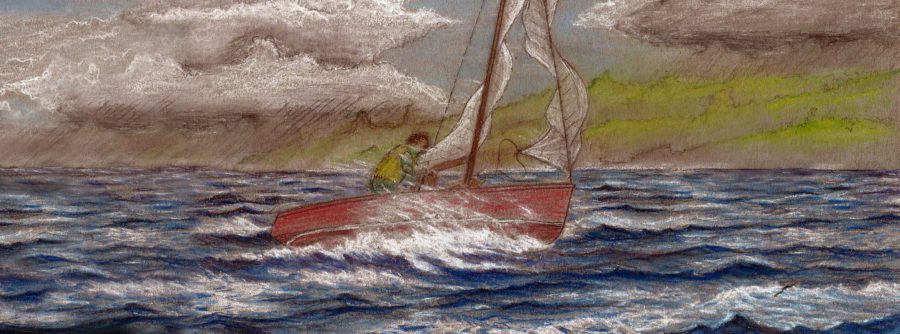

It was hairy, right from the start. Close to shore the breeze was gusty; its direction inconsistent. An accidental jibe would have meant instant capsize, so I tacked downwind, letting the boat round up and spilling the wind in the gusts, and jibing in the lulls. As I moved further out into Searsport Harbor the wind steadied, but it was strong, and the boat felt twitchy, darting ahead, then rounding up and heeling hard, with too much weather helm for comfort or good speed. Obviously, I needed to get out on the trapeze if I were to keep ACE on her feet, which she needed to be if I was to make the best of her planing bottom.

This wasn’t easy. There was that dodgy moment as I crouched on the deck and clipped the harness to the wire—I hadn’t got my weight out yet, the sails weren’t sheeted properly, and I needed to change my grip on the tiller extension. The wrong gust just then, and I’d have been over. I swallowed my apprehension, and managed it without fumbling; now the boat moved faster and toward more open water.

It was clear, though, that ACE was still not happy. The wind continued to increase farther offshore, and gust after gust found her heeled way too far with me hanging on by the skin of my teeth, sheets eased and sails flogging, the tiller hard to windward, and the rudder dragging. Then I would get her back on her feet, struggle with the sheets, only to be knocked down again.

I needed to come up into the wind just a bit, I thought. If I could trim the sails just right and get her properly up on plane, she’d outrun those gusts, and I’d have better control. I had more sea room now, and I set about trying to find that magic combination of sail trim and course that would set ACE free.

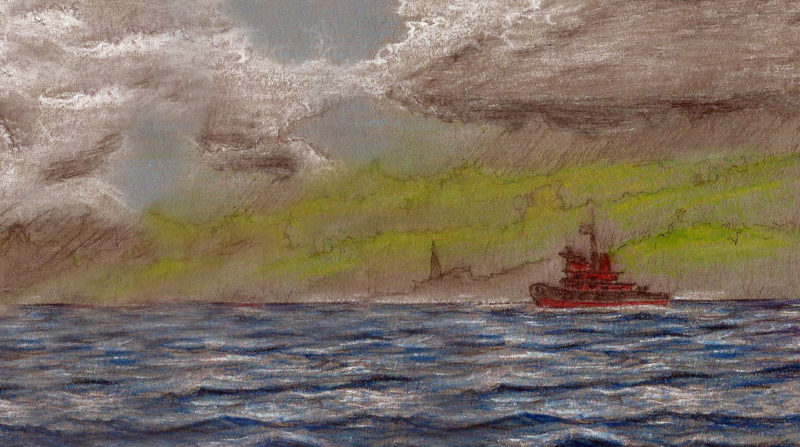

Of course, I should have seen that it was impossible. What followed were two broad reaches, from Sears Island to the Searsport shore, and back to the island, in a series of swoops as each attempt to find the sweet spot led to a knockdown. A tugboat near Sears Island on its way to Belfast would cross my course, and caused me to come up into the wind, and tack to head back the other way. By the time I reached the Searsport shore, the tug had moved out into the Bay; now, I thought, with the harbor to myself, I’ll make ACE fly.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

But conditions were worse than ever. The wind had continued to increase, and again and again I was knocked down, releasing the sheets and regaining control only with the utmost effort. Closing in on Sears Island, the inevitable happened. I could no longer risk a jibe, and as I hardened the sheets and came up into the wind to tack, a gust hit, and we were over.

Now, I had capsized this boat may times in pursuit of thrills, and normally I could get her right back up. As ACE went down, I would climb over the windward gunwale, stand on the daggerboard, haul her back, scramble aboard, and be off again. This routine depended, of course, on the daggerboard being there. This time, it wasn’t. In my haste and trepidation on the launching ramp, I had neglected to secure it with its bungee cord. Now the daggerboard had slipped out of the trunk, and began to float away as the boat continued to roll until she had completely turned turtle.

For a moment I stood on the bottom of the hull, my eyes fixed on the drifting daggerboard. Without it, I was completely helpless, but could I haul myself back onto that slippery bottom if I swam after it? Well, nothing for it but to try, I decided, so in I dived. I retrieved the board, swam back, and found that by hooking my fingers into the daggerboard slot I could just wriggle my way aboard the capsized hull again. I fished under the boat, found a jib sheet, stood back on the chine, and hauled. Slowly the boat came up, and flopped back onto her feet again.

I tumbled aboard and lunged with the daggerboard to shove it back into its trunk, but before I could do that, the wind caught the flogging sails, the bow swung to leeward, the sails filled, and over she went again.

This time, at least, I didn’t have to swim for the daggerboard, but when I got ACE upright once more, the sails filled, and over she went again.

I don’t know how many times the same exact thing happened. In that wind, I just couldn’t get the daggerboard down quickly enough. Without it, there was nothing to stop the bow from being blowing downwind, the sails filling, and the boat capsizing. It seemed futile, but there was nothing I could do but keep trying. At some point I noticed that the tugboat was no longer heading for Belfast, but was sitting motionless a half-mile or so down the Bay. If I hadn’t been so busy, I might have paused to imagine the comments on my idiocy passing between the occupants of her bridge.

My life was not in danger. I was drifting toward the rocky Sears Island shore. At worst I would have swum ashore and made a long, uncomfortable walk back to the launching ramp. The prospects for the boat were more dire. Soon, her mast would touch bottom and probably break. There would be no hope of keeping her off the rocks. I carried a paddle, but there was not the smallest chance that I could use it to work along the shore to a safe landing. The fetch from Searsport to Sears Island is about a mile and a half, but although the waves were not big, they were angry enough to make short work of a light plywood hull on those sullen rocks. Thanks to my wet suit, and my exertions, I was not cold, but I was getting tired. Soon, I knew, I would not have the strength for another effort.

Then, I had an undeserved stroke of good fortune. As the boat came back up one more time there was the merest lull; I managed to ram the daggerboard home and slam the helm down, and the boat rounded up, sails spilling the wind. For a moment I could rest. I bailed ACE out and sorted out the tangle of sheets and halyards in the cockpit.

Arch Davis

Arch Davis“The tugboat was now steaming southward; perhaps I thought that I could show her crew that I knew what I was about after all.”

Now, I should be able to report that at this point I dropped the jib, reefed the main, and headed for home. I did not. The tugboat was now steaming southward; perhaps I thought that I could show her crew that I knew what I was about after all. I got out on the trapeze, and headed back for the Searsport shore, in one more wild pursuit of glory.

I was no more successful than before. The wind was now, if anything, even stronger, and the struggle harder; I did not even come close to getting ACE up on plane. I wrestled with the tiller, eased the main to its fullest, and laid back hard in the trapeze; at every second another capsize threatened.

Then, when I reached the Searsport shore, I could not get the boat to come about. I could not come up into the wind, so I had to try to tack from a reach. The boat was not going fast enough to carry her way through the eye of the wind; she would falter, and fall off on the same tack, heading for the rocks. I tried again, and then again.

Clearly, I had to do something. A jibe was out of the question, and the rocks were getting uncomfortably close. Now, at long last, I came to my senses. I let the sheets run free, scrambled onto the little foredeck, pulled down the jib, unhanked it, stuffed it under the foredeck, and reefed the main.

The boat was still over-canvased, but at least under control. I was able to tack away from disaster on the rocks, and belatedly admitted to myself that there could be too much of a good thing; another attempt at glory would be unwise, I headed back for the launching ramp. I still needed to put my weight out on the trapeze even with the reduced sail, but at least I could work to windward, and pretty soon I was back at the ramp and loading the boat on the trailer.

On another occasion soon after this episode, I was broad reaching well out into upper Penobscot Bay in far too much wind, again chasing thrills, only to find that I had taken on more than I could handle. I didn’t capsize this time, but when I realized that I was really being pretty stupid, and headed back to Searsport, close hauled under just a reefed mainsail, I still needed the trapeze. It was rough out there, with short, steep, tumbling seas. I was well offshore this time, with not another vessel in sight, and I would much rather have just hiked out just on the side decks, but there was no making headway like that, so heart in mouth, I beat back hanging on that slender wire, wishing I’d stayed ashore.

That was about the last of that foolishness. Not long after, I became a father and found that having a small child at home quickly knocks some common sense into your head. I still sailed ACE, often singlehanded on the trapeze, but I gave up the pretense that I could make a 14’ daggerboarder fly in a gale of wind. I have to say that, being more prudent, I had a lot more fun.![]()

Arch Davis grew up in New Zealand, where he learned the elements of boatbuilding and design, and sailed out of Auckland on the Hauraki Gulf and beyond. He moved to Maine in 1988, where he builds and designs boats for the backyard boatbuilder. In 2012, with his daughter Grace, he launched the GRACE EILEEN, a 30’ light displacement cruising sailboat, which they sail on Penobscot Bay and the coast of Maine. He no longer has an ACE 14, but he still takes the original Penobscot 14 out for an occasional row on Belfast Harbor. Plans and kits for his designs are available at Arch Davis Designs.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Good story, Arch!

Thanks for telling it to us.

Yes, it is the child who teaches the parent to become a better climber, caver, and sailor.

Quite the adventure!

Why I am not a sailboat man!

Jim

I admire your ability to capsize and recover, a skill necessary for a small-boat sailor.

I don’t admire your judgement to risk life and limb, another skill for the small-boat sailor.

Stories like yours are why I’m selling my beloved 36′ Herreshoff Nereia to get back into dinghy sailing. Love your designs, love your art, and now I know why.

Jim

Arch, very interesting story, thanks for sharing, and I especially like your drawings!

Yep, gotta listen to that small voice! Had a little lesson in humility about a week ago.

Loved it. So many near tragedies in younger days and so amusing in the retelling.

Sometimes I think the only way to really learn something is to screw up. And hopefully live to tell about it.

I sail one of your Penobscot 17s and even with a couple of people onboard, I feel it gets pretty sketchy around 15-knot winds. I do love the boat. In 10-12 knots it is perfect!

My wife is also sometimes reluctant and does NOT like to get wet so I’ve learned, just put a reef in and relax. I want to sail, not race!

I also have one of Arch’s Penobscot 17s. She is a dream to sail and I’ve had her out in challenging conditions when everyone else was going over. I do have a reef point in her mainsail and have had to use it, then she settles right down to docile.

She’s a beautiful swimmer.