I often get an almost irresistible lure to spend a night in a tranquil, protected anchorage under a starry sky, but sometimes, when I get the feeling that something’s not quite right as I’m getting ready to head out, I’ve learned the hard way to take heed. I didn’t get out on the weekend cruise of the Everett sloughs that I write about in this issue on my first try. I had launched at Marysville ramp two weeks earlier. I had packed for a three-day outing, but I hadn’t been able to leave home as early as I had planned and got underway on the slough late in the day. I had about three hours of daylight left, enough time to make my way upstream to one of the anchorages I had picked out after poring over satellite photos of the area. I had packed the boat in a hurry and was tidying the cockpit even as I was negotiating the bends in the slough. I had my head down for a few seconds too many, and when I looked up I saw the boat was fast approaching the muddy bank to starboard. I yanked hard on the tiller and it split where it wrapped around the rudder head. I brought the rudder aboard and kept going, steering with the outboard.

I had with me all I needed to make a solid repair to the rudder, and normally the incident would just make for a good story. But while I usually relax after I get afloat and take mishaps like that in good spirits, that wasn’t happening this time. I was uneasy about the falling tide, and after breaking the tiller, I was not in the mood for any more of the unexpected. A mere 2-1/2 miles from the ramp I turned around and headed home.

The feeling that led to me to turn tail was not new to me; I had just learned to give it the attention it deserved. Many years ago, I had set out to go kayaking, alone, on Puget Sound while there was a strong southwesterly blowing. The conditions were perfect for some exciting paddling and downwind surfing. I’d gone out many times in the same conditions, always thoroughly enjoyed them, and came back elated. This one time I was feeling a bit off as I paddled the mile and a half in the lee of West Point, just north of downtown Seattle. As I drew near the end of the point I could see the waves tumbling by just beyond the lighthouse. The conditions were perfect.

I paddled close to shore to get ready. I was in a kayak that I was paddling for the first time and taking notes about it in a waterproof notebook that I kept tucked inside my PFD. The pencil I’d tucked under the bungees on the foredeck had disappeared, but I had a spare stashed behind my seat. I opened the spray skirt and fished around for it but couldn’t find it. I scooted out of the cockpit, to sit on the aft deck to get a clear shot at the cockpit. I was quite accustomed to doing that while afloat, but I was feeling impatient and annoyed. I know now to regard that as a red flag, especially when I’m embarking on a solo outing.

When I shifted my weight aft, the stern went under. This kayak had exceptionally fine ends and could only adequately support me when I was in the seat. I grabbed the pencil as water began to pour into the cockpit. That was just another nuisance. I was wearing my dry suit and it wasn’t a problem getting wet, so I slipped into the water, made my way to the bow and flipped the kayak, pouring the water out. It was only I after I returned to the cockpit to get back aboard that I took notice of where I was. The mood I was in had put blinders on me and I hadn’t noticed that I was drifting rapidly away from shore. I’d soon lose the protection of the lee and have to work against wind and waves to get back aboard.

There was a mooring buoy with a workboat a few boat lengths off the bow and slightly downwind. I took hold of the kayak’s bow toggle and swam toward the buoy, which I drifted past but was just able to reach the boat’s bowline. If I’d missed that, there wasn’t anything else I could grab onto keep from drifting out into open water. I stayed in the water with one hand on the line, the other on the toggle, and, for the first time that afternoon, shook off the myopia and took stock of my situation. With my head cleared, I got aboard the kayak, paddled back into the lee, and went home.

Since then, I have paid more attention to my inchoate misgivings. There have been times that I’ve suited up, packed up, driven to the ramp, and even launched the boat, but turned around without leaving the dock. If I’m feeling something is not right, I’d rather deal with that on the way home from an outing cut short than on the way out where turning around is not so easy.

When I launched the boat the second time, for the trip you can read about in this issue, I knew that there could well be gear I’d left behind and some things might not go as I had planned, but I was in the right state of mind and up to working through whatever problems I would encounter.![]()

I cannot count the number of times that the “little voice” has saved my bacon. Bacon, Boat, Bride, and the Basket they all came in on.

Yes, indeed! Paying attention to your higher angels that want to protect you is always a smart move.

Perhaps the little voices were from all of us boatbuilders, adventurers, and dreamers who have benefitted greatly from your teachings, wisdom, and help. Glad you turned around.

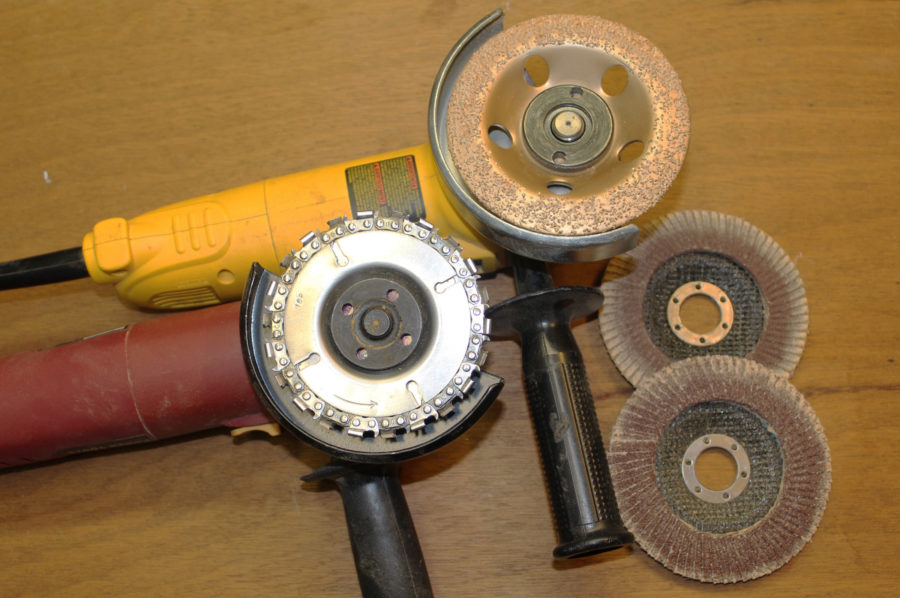

The little voice spoke to me as I was most of the way thru the cut on the moulding cutter head. “Stop here, Dummy” No! only have 6 more inches to go.

Three finger tips, $30,000 in hospital bills, and the purchase of a Sawstop later, reinforced the “little voice” theory. The “little voice” has saved me before but not on this day as I was too arrogant to listen this time. Listen to the “little voice.”

“Little voice,” “Higher Angels,”…. Holy Spirit?

I like going out on my own too, there are no distractions and you can enjoy nature so much more in peace.

But it does have that greater element of risk of course. You need more than just planning and preparation because plans always go wrong whether it is a big or a small issue.

That “more” in my opinion is intuition, and intuition is the cumulative knowledge and experience that you have gained in life. It is not conscious but manifests itself in a feeling of unease, something does not fit.

As I get older, I rely increasingly on intuition. Always err on the safe side, and make it a pleasure not a stressful experience.

I’m afraid that’s all mumbo-jumbo. Don’t let your fears become your dictator. Might’a had the best weekend in years after that.

There may well be times when everything turns out well in spite of uneasy feelings that might arise at the outset. I’ve gotten used to being nervous, and yes, even afraid, when I’ve set out on many of my solo travels by boat, by bicycle, and on foot, and almost without exception, they turned out to be rewarding experiences. But I’d spent weeks if not months preparing for them.

If you turn back, you may never know what you’ve sacrificed for a vague hunch. In the case of my Everett cruise, I had my hunch confirmed. I discovered that in my haste to get on the road, I had forgotten to put even one anchor aboard. I usually bring two, each with chain and rode. Even though I’d lost one anchor on my second night of the cruise I did embark on, I had a spare and could have spent another night out. On my return to the sloughs, I saw the two places I had planned for overnight stays on the aborted trip. One was the cattail marsh I mentioned in the story, the one blocked by a log and with an uneven bottom. The other, a small cove off Ebey Slough, I passed by on my loop around Otter Island without even registering it as a possible anchorage.

On the long cruises I made in my late 20s and early 30s, I spent nights in places I’d never been before, but I always looked for possible camp sites and anchorages long before dark. The one time I didn’t do that was on my row down the Mississippi River. I had passed by several good overnight spots with the last of the daylight to head for a landing I had marked on the chart, only to discovered that the so-called landing had no safe place to come ashore. I wound up rowing downriver for a couple of hours in the dark, and by the time I found a patch of sand where I could get off the water, freezing spray had coated the back of my jacket and the foredeck of my sneakbox with ice and I was dangerously hypothermic.

The uneasy feeling, the little voice, the higher angels—whatever one chooses to call it—may have some rational basis. I can easily attribute the feeling I’d had on my first attempt at the sloughs to my past experiences now that I’m looking back on it, but at the time my thinking wasn’t so clear. The feeling’s advantage is that it precedes the reasoning; there are times when it is just as well founded and just as worthy of heeding.

Good article. Sound advice. Sometimes the “voices” in my head alert me to the dangers aheaed and suggest that IF I am going to continue on the questionable path I am considering I should take specific safety measures. I have learned to ALWAYS listen. I lose a lot less blood when I heed the voices.

Two months ago I set out alone in my old 20′ cabin cruiser, as I had done many times before, for a night prawning. Leave the mooring about 5 pm, anchor as usual in the narrow channel, cook dinner, catch a few prawns from dark until about midnight, cook them onboard, sleep, and then go home after sun-up. While stowing the gear on board I noted that there was what would be, at anchor, and adding to the incoming tide, a solid 25-knot wind over the port bow, but while the voice in my head said “this really is not a good idea,” I had put in all the effort to prepare and departed as planned. Any other prawning site was going go be even more exposed. On site, I had the anticipated problems getting the bow and stern anchors in the right spot. Every time I left the helm to drop the bow anchor, the bow and then the whole boat swept away toward the surrounding oyster leases not 20 yards away. After 40 frustrating minutes, and finally anchored in place, I opened a beer and started to cook dinner. The wind continued until a much bigger gust lifted the bow anchor and I was in deep trouble. I’m 71 years old and for the next 20 minutes felt all of them. With the boat eventually extracted from sandbars and oyster leases I was exhausted. I made a few half-hearted attempts to get the boat anchored safely but common sense finally prevailed and I went home in the dying light. What did I learn?

1. Find a way to get the bow anchor down without leaving the helm (done).

2. Consider a bigger anchor with more chain (not feasible), but most of all,

3. Listen to my that voice in my head.

I have good reason to listen to that voice since it saved my bacon on a narrow winding road 30 years ago but on this occasion I didn’t. This time I might not have paid with my life but could have paid with my boat.

Some years ago Daniel Kahneman and Gary Klein wrote an article in American Psychology on when to trust your gut instinct when making business decisions. Three of the conditions they mention work equally well for paddling, rowing, or sailing on my view:

1. The familiarity test: Do you have deep experience with similar situations?

2. The feedback test: Do you have reliable evidence from the past when you have trusted you instincts?

3. The measured-emotions test: Are your emotions moderate or charged?

I think that thinking consciously about these three conditions would serve us well when deciding on whether to rely on gut instinct.

…and they work for mountaineering, another solo pursuit of years past. The focus is sharp, in the zone when nightfall approaches, the air feels different, the route not quite right. More care is taken with each step and escape routes are tallied with greater frequency. I would also point to the clarion call of loved ones: spouse, children, grandkids. I think their collective voice is heard a bit more clearly, “You’re not really going to leave us for a summit or ill-advised stream crossing, are you?” So many angels…

Some call it recognition-primed decision making. We all have “slides” from experience and the experience of others. We compare our situation to our slides. Sometimes the gut is ahead of the brain in recognizing a slide we don’t wish to re-experience.

All contributors say sensible words on their own experiences, some more generally useful for readers than others but all worth noting. However, as a sea kayakker (Holland, Denmark, Scotland, England, river estuaries, sea lochs, North Sea coasts, Baltic inshore water) it strikes me that a grave error that was the cause of a series of problems was consciously made: opening the watertight system that should be maintained at all times at sea. Never ever lose your paddle, never even think of opening your sprayskirt. Intuition or inner voices simply do not substitute for common sense.

I should know, had to swim for my life in a Scottish loch full of very wet, very cold water.

Thank you for writing about this. I’ve had the same experience in motorcycling. More than once, I’ve been out on the bike, and realized that I really shouldn’t be riding, usually after missing a clue about developing traffic situations. I am learning to pay closer attention to how I feel, and to be OK with changing my mind and my plan, whether it’s the motorcycle, the rowboat, or the kayak. Thankfully, we seem to wise up a bit as we age.