Sitting in my shop was a freshly oiled, clinker-built 14′ faering. Three friends and I, working in Russell, a coastal town on the north end of New Zealand‘s North Island, built the boat over the course of just two weeks; it was the first boat of its kind ever to be produced in New Zealand. As we prepared to carry the finished boat out of the shop and into the street where friends and reporters were eagerly awaiting the fruits of our labor, it occurred to me that we’d never measured the doorway.

I set out on the path to building this boat three years earlier when I had traveled in the middle of winter to Nordland, a Norwegian county that straddles the Arctic Circle, to produce a film about how Norwegians, considered some of the happiest people on Earth, remain so even when the sun does not shine for months on end; where the darkness is interrupted only by an ethereal blue light.

Vern Cummins, my partner in making documentary films, had come with me to make a film about a man we had yet to meet, Ulf Mikalsen, a traditional boatbuilder who is one of only a handful of people left in Norway making a living building the iconic 18th-century Nordlands boat. “Fly to Bodø,” he told me over the phone, “and drive north from there, crossing on the ferry until you reach the small town of Kjerringøy. There, go past the church on the right; my house is the one with the red trim around it.” And that was that.

Two weeks later, frost crunched under my boots as Vern and I stepped off the plane in Bodø. We drove in the February twilight and by the time we arrived at the only house in Kjerringøy with red trim a heavy, wet sleet was hammering down. Out in front of the car, through the downpour, I could just make out a figure in dingy oilskins approaching us. He walked up to the window beside me and pushed back his hood, revealing a broad smile. It was Ulf, a man who would leave an indelible mark on my life. “Velkommen til Kjerringøy,” he smiled. “Welcome to Kjerringøy, Jamie.”

photographs by the author

photographs by the authorThe village of Kjerringøy is nestled among the fjords and coastal mountains of the north central Norwegian coast. The red and white buildings on the left are part of the Kjerringøy Museum and Old Trading Post.

Inside Ulf’s cabin, it was apparent he had a love of natural materials and a superlative skill for working with them. The timber post-and-beam frame enclosed a warm, modest room where, in typical Scandinavian fashion, everything, even the most utilitarian objects, was handmade and beautiful. Hanging over the kitchen sink were clay mugs made by Ulf’s wife, Ingvild, each adorned with the names of everyone in the family. Ulf wore a hand-knit wool sweater with a Nordlands boat decorating his chest and his name stitched onto its sleeve. Ingvild showed us around the house; downstairs through a hidden doorway in the wall was the sauna, a vital Norwegian staple—without which communities like Kjerringøy would be unable to function socially during winter. Where else would you discuss politics, offshore oil drilling, or the best recipe for infusing home-distilled aquavit, if not in an excessively hot, cramped room with strangers wearing no more, and often less, than a towel?

In his shop in Kjerringøy, Ulf works on a nearly completed Nordlands boat.

Prior to becoming a boatbuilder, Ulf was a carpenter and student of social anthropology. His studies took him as far as southern Africa, as well as southern Norway, but he admits, “I knew I couldn’t live there for very long.” The call of the north lured him back, and he settled in the small town of Kjerringøy where he took a job at the museum.

At the museum, housed in an historic 17th-century trading post on the shores of the fjord, Ulf first worked on the restoration of Nordlands boats and on some of the buildings on the property, and discovered a love for joining history with craft. He enrolled in a boatbuilding school in Saltdal and returned to the Nordland Museum as resident craftsman, director, and general manager of Kjerringøy Handelssted, the Kjerringøy Old Trading Post.

Ulf’s Sami knife, forged by hand and set into a handle made of reindeer antler, is one of his most-used boatbuilding tools.

Next to the museum is Ulf’s boatshed and workshop where I spent the dark hours of the Norwegian winter mesmerized by a master artisan at work. The boatbuilders I’d known back in my home on Cape Cod worked with electric planes, drills, and band saws, but Ulf shaped sheerstrakes by eye with a Sami knife and scarfed planks with an axe. I’d never seen precision like it in my life, and I occasionally stood in the middle of a floor carpeted by fresh wood shavings contemplating what I ever had to show for myself after a day’s work back in my office: never anything so substantial nor so fragrant. “I’m not exaggerating when I say that nine out of ten visitors who stick their noses into my boatyard take a deep breath, smile and exclaim, ‘It sure smells good in here.’” It was time to toss in the towel, learn to speak Norwegian, and become an apprentice boatbuilder. I mentioned the idea to Ulf, and he just smiled.

Over the next week, Vern and I filmed a documentary that we would title “The Fox of Bloody Woman Island” (Mikalsen means “son of the Fox” and Kjerringøy translates to “Hag Island,” or as Ulf calls it, “Bloody Woman Island).” On our last day of filming, Ulf launched the largest of his Nordlands boats for us. It was only February—several weeks earlier than normal for Nordlanders to launch their boats back into the recently thawed waters around Kjerringøy—but Ulf could see this was the moment we had been waiting for.

Nordslands boats have been sailing Norwegian waters for over 1000 years, and Ulf is making sure they’ll continue to grace the coastline in the future.

We rowed out of the harbor, set the square sail, and the boat moved through the waves flexing like a snake. In the brisk winter twilight, listening to the waves slap against the hull, I began to understand why Ulf chose to live here and pursue this passion, despite the fact that the young girls working in a store near his boatshop earn twice as much as he does as a boatbuilder. “I made a decision,” says Ulf, “not to make a lot of money, but to do what I really wanted to do. Let’s say I feel quite happy about my life.” As we sailed the Nordlands boat I trolled a line over the side and landed the biggest, laziest cod I have ever caught.

About a year after my time in Nordland, my wife and I emigrated from the Falkland Islands to New Zealand where I began working with a handful of friends to establish an adventure education center called Adventure For Good. We’d settled in Northland, New Zealand’s northernmost province, on a beautiful, protected inlet in the Bay of Islands.

This was the area where the first European missionaries landed, setting up missions and trading posts at points all along the coasts. Just across the bay was the small town of Russell, New Zealand’s first capital and an important 19th-century whaling port. Looking to introduce new opportunities to the area, we decided to establish a traditional boatbuilding school to celebrate and foster the region’s rich maritime heritage. So I mentioned to the board of directors of Adventure For Good that I in fact knew of a skilled boatbuilder in northern Norway who uses the natural curves in the roots of spruce trees to create his boat’s ribs. This impressed them as it had impressed me, and the next morning my boss told me he’d received approval from the board. Within weeks a plan was hatched to bring Ulf and Ingvild from Nordland to Northland to build a Norwegian faering in the gutted remains of our Russell shop front.

A few months later, I drove to Auckland to pick Ulf and Ingvild up from the airport. It had been nearly three years since I had seen them, and I was suddenly overcome with feelings of excitement and nervousness. Would we be able to build this boat and justify this entire ordeal? As I pulled up to the arrival area of the airport, Ulf and Ingvild were already waiting for me. It was easy to spot them; Ulf was wearing a “Kjerringøy Handelssted” T-shirt with drawing of the Trading Post in the background and a Nordlands boat in the foreground.

After our Norwegian friends settled in, it was our time of reckoning. Word had gotten out about what we were up to, and we needed to get ready to build our boat. Ahead of Ulf’s arrival, we had enlisted the help of John Clode, a local boatbuilder, to organize tools, materials, and our workspace. John was an equally inspiring craftsman, largely self-taught, and had restored several steamboats for use as charter vessels around New Zealand. Like Ulf, he was an accomplished sailor, commercial fisherman, and adventurer. John and his wife Bridget opened their home to Ulf and Ingvild for their six-week stay. John, it turns out, had an immense interest in Nordic design ever since hitchhiking through Troms, one of Norway’s northernmost counties, 40 years prior in search of a fishing vessel to crew on. To my relief, John and Ulf hit it off and soon were inseparable.

The keel was assembled in the old boathouse before we moved the project to the workshop in Russell. Ulf held the stem in place to give us our first glimpse at the shape of the boat.

For our build, we wanted to build a fearing, a four-oared boat, but also hoped to do something unique, so we had left the choice of the type up to Ulf. He had given it some thought before leaving Norway and had chosen a spissbåt, a lapstrake working boat from 20th-century coastal Norway. A spissbåt is literally translated as “tip boat” or “pointed boat” and is distinguished from other similar types by that sharper prow. From the early 1900s through to the 1960s the spissbåt was one of Norway’s most popular boat designs. Prior to the introduction of roads along Norway’s vast coastline, the spissbåt was often built by its owners, who were responsible for daily duties like catching supper, taking the family to and from church, and ferrying fresh supplies home. The spissbåt’s eventual demise in the 1960s was largely due to the rising popularity of the outboard motor. The double-ended spissbåt was designed to be powered by sail and oar, but was never adapted to carry an outboard motor.

In Norway, the spissbåt is traditionally built of Douglas-fir and spruce, neither of which are in ample supply in our part of the world. That would become our first obstacle. What we hoped would be the solution presented itself in the form of an enormous boatshed stocked to the ceiling with rare and exotic woods collected from across the globe. It belonged to one of Adventure For Good’s directors, an enthusiastic Russell businessman who was more than happy to let Ulf and John rifle through its contents.

The pair looked like kids in a candy store lifting up rotting canvas covers and rummaging through dusty piles. Within a few hours, my pickup overflowed with planks of timber. We would use red cedar and teak instead of fir and spruce, and copper roves and nails instead of iron, which would not hold up well in the South Pacific. Our New Zealand spissbåt would be more fragile than a traditional Norwegian one perhaps, but it would also be lighter, faster, and just as beautiful. Ulf had never worked with cedar, but John was confident it would serve us well.

Hand axes have always been essential tools in traditional Norse boatbuilding. Ulf found an old hatchet in John’s garage and put a sharp edge on it, transforming it from a crude chopping implement to an edge tool for fine work.

At the boatshed, we milled the lumber and Ulf began construction by shaping the 14’ keel with a hatchet. I’d seen him do this in his shop in Norway, but this was new to John, who intently studied Ulf’s technique as each precise strike peeled away wood fibers in shavings instead of chips. John followed Ulf’s lead, chopping with light glancing blows and dressing newly cut surfaces with the axe head in both hands, fingers lined up on the side of the axe and pushing the cutting edge like a chisel.

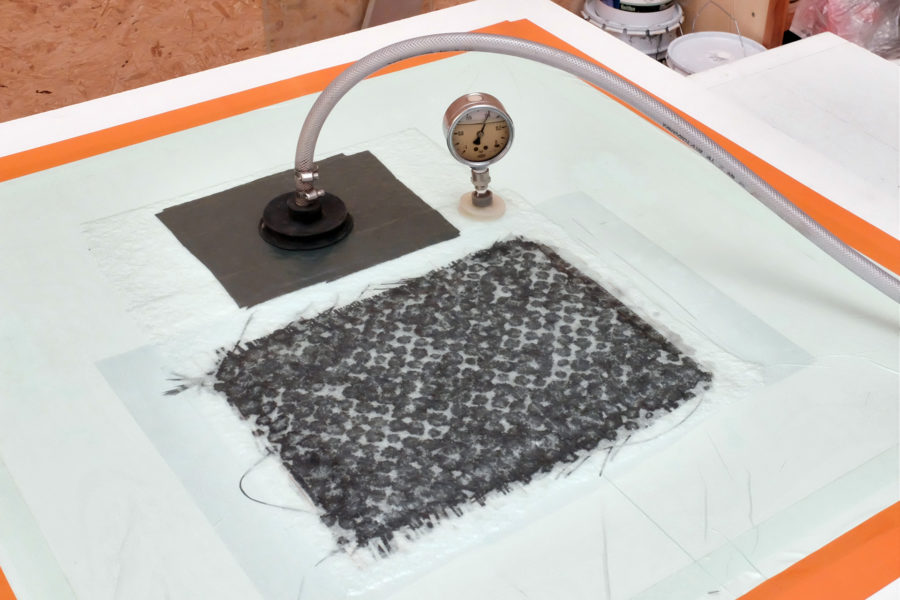

When the keel was complete and the stems were attached to it, we moved the project to the shop in Russell where we’d resume construction. We set the boat’s backbone upright on a heavy beam resting on chocks on the floor. We turned our attention to the planking. Unlike many lapstrake boats, the spissbåt doesn’t begin upside-down, but rather it is built right-side up. In the Nordland style of boatbuilding there is no steaming involved in getting the planks to take their shape in the hull. Instead, each is fixed to one of the boat’s stems before being gradually and gently bent into place using one’s hips and cut-to-length, wooden props that hold tension between the interior side of the plank and an overhead beam. We pinched the laps together with shop-made wooden clamps called Brenne klammen. Ulf had brought one with him for reference and John used it to make several copies.

One of Ulf’s handmade instruments, a båtlodd, measures the angles of the planks. Much of the shaping of the boat was done by eye and feel rather than from precise measurements.

Coaxing the planks into the necessary curves and twists was a critical step in the boat’s construction—too much pressure could crack or split a cedar plank, and we would have to make a new one. Ulf listened to the boards as they bent and felt their strain against his hip. Sensing the wood’s limits, he manipulated the planks as easily as if they had been steamed.

Together we slowly planked the hull outward and upward from the keel. Ulf cut plank sections to shape on the bandsaw, then cut a scarf in one end using his axe and Sami knife. He checked the other end for fit against the stem, refined further by hand, and repeated until he nodded that it was time to make it permanent. Between strakes Ingvild and John laid a strip of thin cotton twine over a dribbling of pine tar heated slowly to thicken the consistency of honey. No other sealing was required; the cedar would swell when the boat was in the water, and the planks would press against each other to tightly seal the laps.

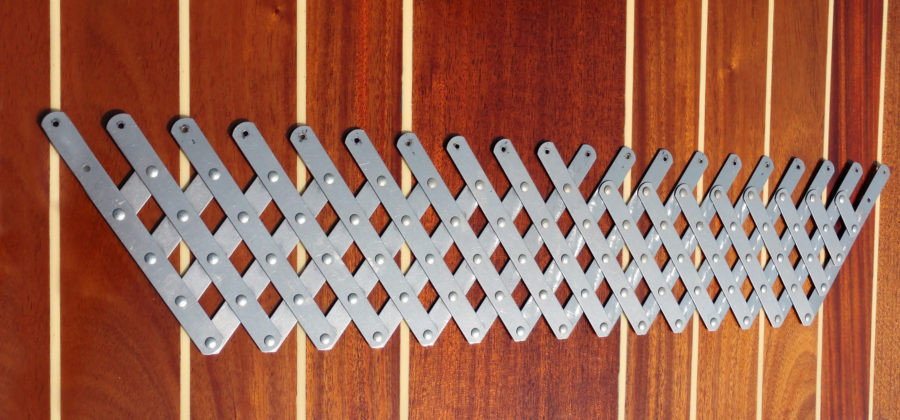

The Brenne klammen is a planking clamp named for Harald Brenne, a Norwegian boatbuilding instructor. It has a long reach to hold laps on wide planks and can be operated with one hand.

It was often my job to stand by ready with a Brenne clamp as Ulf brought over a new plank. With the plank locked in place, John used a traditional handheld gimlet ready to bore holes for the rivets. This was hard going and rough on the wrists, but as we became familiar with using the simple hand tools, we gained a greater appreciation for the old ways and worked through the tasks faster. In the end, we barely missed our power tools.

The sides rose up and a spissbåt took shape. “In Norway this would be the most expensive version of this boat I have ever built,” Ulf said, “but I am happy to see the different woods responding well to their new position in life.”

Ulf makes one last final check of the fit before making this strake permanent. Note the wooden props both above and below the hull helping it maintain its shape until the frames can be fixed in place.

During the construction, people stopped by daily to take a peek at the unusual kind of boatbuilding that was going on in the shop. The visitors popped in so frequently and became such a distraction that we were hardly getting any work done. I took a scrap of wood and a paintbrush and made a sign to hang on a chain across the open doorway. It read, “Craftsmen at work. Don’t feed the boatbuilders!” After that the curious continued to stop by, but were satisfied to peek through the bay windows and double doors. We felt like zoo animals, but our work resumed at a steadier pace.

After the hull was planked, Ulf and John fastened the beautiful teak gunwales, breasthooks, and coaming, then the cedar thwarts and floorboards. Two pairs of oars took shape on the workbench.

Ulf fits the first of the frames. The small gaps outside of the frame at the keel and the plank laps allow water to pass through.

As the launching of the spissbåt drew near, we held a competition among locals to name our boat. I was surprised at the number of entries we received and the thought that had gone into the names. I wrote the submissions down on a scrap of spare cedar, and each of us builders cast a vote for the name we liked most. The winner was AORUA, a Maori word meaning “Of two worlds.”

Natalie Gallant

Natalie GallantAfter weeks of hard work, Ulf, Ingvild, Jamie, and John get ready to launch the spissbåt at the beach in Russell.

With the weeks of hard work behind us, it was time to move the boat out of the shop and carry it to the beach. Ulf, John, a few friends, and I lifted the spissbåt and carried it toward the shop door. It was clear that the boat was too beamy to squeeze through. We turned the boat on edge and easily slipped through the doorway. Outside we were surrounded by friends, townsfolk we recognized, and people we had never met before. Cameras flashed as we carried AORUA a block down to Russell’s waterfront. By the time we reached the beach where we’d launch, there were eight of us carrying the boat. We set AORUA down on the gentle slope of gravel in front of a 190-year-old hotel. With dozens of people circled around us, John popped open a bottle of champagne and the cork went flying over the boat. He poured champagne over the stem and white foam flowed across the breasthook.

Ulf takes to the oars in Kororareka Bay off the town of Russell.

We slid AORUA into the water, and Ulf and John stepped aboard. I kicked off my sandals, handed the oars to them, and climbed over the side to take my seat in the stern. They set the oars between the thole pins and turned AORUA parallel to the crowd gathered on shore. The honey-colored hull gleamed in the sunlight. Ulf and John took their first stroke together, the spissbåt slipped cleanly through the glassy waters, and in less than a minute we were at the other end of the bay, a hundred meters or so away.

Natalie Gallant

Natalie GallantOne of the launch party takes a turn at the oars with Jamie rowing in at the forward station and Ingvild seated in the stern.

We returned to the shore beaming. Ulf and John hopped out and were replaced by a crew of interested locals who had cheered us on throughout the process of building the spissbåt. New crews formed with friends and strangers alike, brought together by a boat from the other side of the world. Though AORUA was born in New Zealand, she is undeniably Scandinavian: handmade, utilitarian, and beautiful.![]()

Jamie Gallant was born on Cape Cod and from a young age become fascinated by the area’s maritime traditions. He went on to explore this theme further as a documentary filmmaker, sailing Nordland boats in Northern Norway and retracing the story of the Columbia Expedition—the first American expedition to circumnavigate the globe—through treacherous seas off the Falkland Islands and Tierra Del Fuego. Today, he is a rescue specialist in the Coast Guard.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

A beautiful boat for a beautiful town, and an excellent write-up.

I wish that I had known that it was being built while I was there! Would have loved to have seen it and not feed the craftsmen!