From the 1,900′ summit of Mount Maxwell on Salt Spring Island, my wife and I looked out over dozens of emerald islands spread out all along the southern horizon. With their forested slopes and rocky shores, these islands are the broken edge of the land, where a continent buckles under an ocean. I opened my sketchbook and drew each hill and bay, and each shadowed shore rising from a silvery sea. We had caught a glimpse of British Columbia’s Gulf islands while aboard the ferry on its hurried passage from the mainland to Vancouver Island, but as I drew the outline of each island I couldn’t help but yearn to trace their contours in my own boat, following my own route on my own schedule.

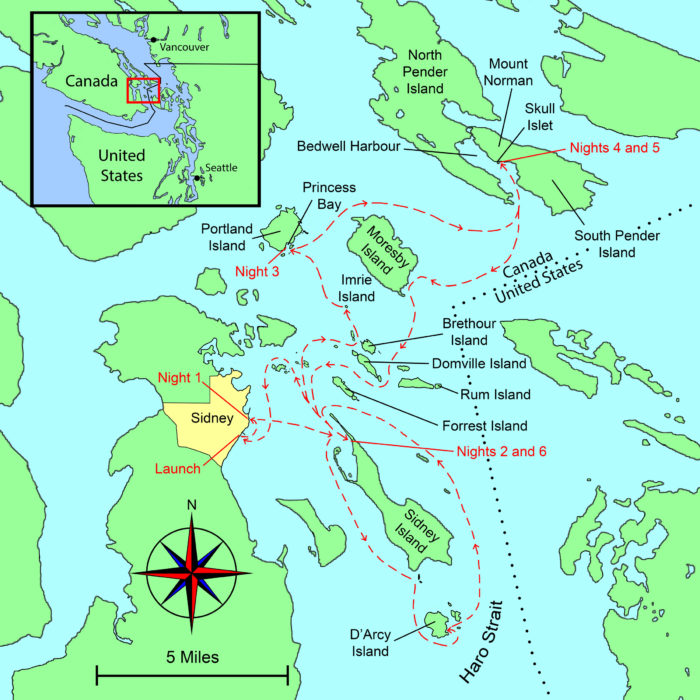

Three years later I slid ROW BIRD, my 18′ Iain Oughtred Arctic Tern, into the waters bordering the town of Sidney on Vancouver Island. I was launching very late in the day—I’d just finished a 200-mile drive from my home in Portland, Oregon, followed by the two-hour ferry ride—but I didn’t mind. Ahead of me I had a week to cruise among the islands I had drawn from the heights of Mount Maxwell, now visible, 8 miles to the north and looming over Sidney’s shore. The southern Gulf Islands, scattered to the east, promised an ever-changing horizon along with the pleasures and challenges of new anchorages.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

I usually sail with friends, but this would be a solo trip with the freedom to do as I pleased without negotiating routes, times, or decisions. If I wanted to spend two nights in a secluded campsite or to row all day, I could. My travel would be limited only by the tides and winds and my goal was to shake myself free of electronic leashes, bolt from thoughts that tie my brain in knots, and find my freedom in the present moment.

The sun had started to set, but the air was still a balmy 65 degrees and the honey-colored water was placid and inviting. It was mid-June, and Canadian kids were still in school, so the flood tide of summer tourists hadn’t started. ROW BIRD was the only boat on the water. With no wake but my own, there was barely a ripple to be seen in any direction. I rowed a half mile north along Sidney’s suburban edge to a cove I’d found while studying satellite photographs on my computer back at home. It had just room enough to allow my boat to swing at anchor between a commercial dock, the boulders protecting a waterfront trail, and a tattered, creosote-stained pier.

As I set up my cockpit tent, three pairs of walkers on the trail stopped to watch me preparing to spend the night aboard. I stretched my nylon cockpit tent between ROW BIRD’s masts, and tied down the rib-like battens that make the whole thing look like a Conestoga wagon on the water. With my sleeping bag unrolled on the floorboards, my pillow and book at the head of my bed, I lay down with a view of waterfront hotels and condos illuminating the edge of town. People watching me from shore must have thought a small open boat would be cramped place to spend a night, but being aboard ROW BIRD felt right; after years of camp-cruising, I knew every inch of the boat, and her familiar motion in the water made it easy to make myself comfortable and content.

photographs and video by the author

photographs and video by the authorAlthough lacking facilities developed for small boats, downtown Sidney made an easy first overnight and a convenient stop for anything I needed. Within a five-minute walk of the water I found two grocery stores, lots of restaurants, and shops.

I awoke earlier than I’d hoped, thanks to an early-morning delivery truck rumbling by. Soon after the sunlight hit the water I brought the boat to shore, and three people approached. A young couple who love to kayak told me about their favorite stops in the islands. Then a silver-haired woman in an exercise outfit asked where I was headed, and when I told her of my plans, she spoke of her own small-boat adventures through the islands and stared wistfully at the islands a few miles away.

The tide was rising, so I set a 4-lb claw anchor off the stern with an Anchor Buddy, rowed ashore to set my 8-lb Danforth-style anchor on shore and let the elastic stern line pull the boat into deeper water. With ROW BIRD afloat, I headed for Beacon Avenue, Sidney’s main shopping street, and bought a cup of coffee and a pumpkin scone; I was ready to start my journey.

After stowing my anchors in their canvas bags, I took to the oars. I set a course 8 miles south-southwest for D’Arcy Island and listened to the weather report on my VHF radio. In Canada the weather is announced in both English and French, so the broadcast cycle is twice as long as what I was used to. Impatient to get to the English version, I struggled to translate French and convert metric measurements, reaching back to rusty skills acquired in high school. A high wind advisory had been issued for Haro Strait, the dog-leg channel separating B.C.’s Gulf Islands from Washington State’s San Juan Islands.

The wind would be a problem for me because D’Arcy lies in the middle of the 7-mile-wide north-south leg of the strait and is exposed to an uninterrupted 20-mile stretch of open and often rough water to the south. Not quite 3/4-mile long and 1/2-mile wide and without any well-protected anchorages, D’Arcy sits apart from the rest of the Gulf islands and its isolation helped shape its history. For three decades, ending in 1924, it served as a leper colony for Chinese immigrants; during Prohibition it was a hideout for bootleggers smuggling whiskey into the States. Now part of the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve, D’Arcy was high on my list of islands to see, but with the wind predicted to build over the next few days, I had a small window to get there and back.

I should have hustled if I really wanted to explore D’Arcy, but I found the rocky shores of Sidney and James islands were less developed and more enchanting than the San Juan Islands I was familiar with. And no one was out on the water. Wherever I looked, if I saw boats, they were way out in the distance.

I had to navigate rocks, islets, and tidal currents, keeping an eye out for the many ferries that use Sidney as a hub. They generally stay on a defined route, but some of the passenger ferries reach speeds of up to 30 knots and can sneak up in a hurry if you’re not paying attention.

After three hours of rowing and slow, close-hauled sailing, I approached D’Arcy’s north end—a craggy, coarse shoreline behind offshore rocks and beds of hose-like bull kelp. A few fragments of lichen-encrusted concrete walls, the remnants of the leper colony, stood eerily at the edge of the forest. The wind was patchy as I neared the kelp beds, so I raised the centerboard and took to the oars. Kelp wrapped itself around the blades like spaghetti spun on a fork, forcing me to stop every few strokes to free my oars.

The large logs lining the shore of D’Arcy Island are a testament to the strength of the winds and storms that hit the exposed southern shore. Visitors arriving by kayak and other hand-carried small craft can take advantage of a primitive campground near the cove, but I had no safe place to anchor if the water got rough.

I rowed the mile around the west side of the island and arrived at the southernmost point close to low tide. Bony fingers of jagged granite stretched into the water. Even for a small boat, this was a treacherous place to maneuver; every few strokes I had to look over the bow for unseen rocks. After several moments of uncertainty, I spotted a silvery mast behind a rocky outcropping and knew I’d come to a place more suitable for landing.

“Ahoy,” I called to a deeply tanned man relaxing in the cockpit of the sloop, “how’s the anchorage here?”

“Fine now,” he answered. “But I was anchored out here recently, and that time it was too rough to go ashore and too rough to leave. I didn’t sleep so well.”

If the wind that had been forecast didn’t kick up I could spend the night anchored here near the gravelly beach, so, hoping for the best, I pulled the bow of my boat ashore and set an anchor near the beach wrack from the last high tide. I spent a few hours exploring D’Arcy’s brushy trails and drawing in my sketchbook, but late in the afternoon, the treetops above me swayed as the predicted southerly front arrived. Thinking of the sailor’s recent experience, I decided that staying could make for a dicey situation. I boarded ROW BIRD and headed north for the more sheltered waters that the other Gulf Islands could provide.

Although I had been looking forward to spending a quiet night at D’Arcy, I wasn’t disappointed by the change in plans. I had no specific route to follow, just a list of places I wanted to see, and the weather, tides, and currents would guide me. Content to go with the flow, I felt a greater sense of freedom than I would have had if I’d held tightly to a fixed itinerary that put me at odds with the elements.

The locals warned me that Sidney Spit can get quite crowded during the summer when the passenger ferry is bringing visitors from the mainland, but I arrived in the off season and it was very quiet.

The front’s early wind provided a gentle push and I sailed northward on a broad reach, winding my way through a series of rocky islands, uninhabited but for the scores of seabirds I could hear calling in the distance. Sidney Spit on the north end of Sidney Island’s was the one bit of island coastline that was free of rocks, but I was unsure about it as a place to go ashore, having read that it can be as crowded as Coney Island on a hot summer weekend. But when I approached the slender mile-long neck of sand at the north end of the island that evening, just two people were strolling the beach; a quiet group of kayakers had settled in at the campground, and a few larger craft were tied to the mooring buoys, and floating above a vast eelgrass bed. The dock was empty—I’d have it all to myself. At dusk, voices in the distance softened, then grew quiet, and the only sound was the wind ruffling my cockpit tent.

Just before dawn I was awakened by a raft of river otters foraging and splashing around the docks; I got up before the sun was in the sky, and the light scattering of clouds indicated a clear day ahead. I intended to head northeast toward the eastern Gulf Islands that back up against the rough waters of the Strait of Georgia. The first step was to make the 8-mile passage to North and South Pender, a pair of islands separated by a slender 30-yard-wide gap. During the night, the flood tide had flowed into the 100-mile-long strait and in the early hours of the morning all that water retreated on the ebb, straining through the passages between the Gulf islands. I tried to time my departure to coincide with the slack tide’s still water and catch the flood that would push me much of the way to the Penders, but my start was a bit too early, and I made it only about 4 miles.

Traveling by a shallow-draft boat let me get in among the kelp and massive rocks to watch intertidal life and seabirds. I made a temporary anchor by wrapping the painter around a few thick stalks of kelp.

I had to tie my boat in a patch of kelp off Imrie Island, a 70-yard-wide grassy islet, and wait out the last of the ebb. It was a peaceful place to be—the kelp dampened the waves and the patches of smooth water between its stalks provided a clear window to the underwater world. Milky white jellyfish the size of saucers pulsed below, and dull-green fish hid in the kelp fronds. Oystercatchers with their bright blood-orange hued beaks paced about their stony nests on the outcroppings of lichen-tinted rock surrounding Imrie.

By the time the tide turned and the flood began to work in my favor, an intensely puffy headwind was blowing from the northeast against the current, causing steep choppy waves with a height that matched to ROW BIRD’s freeboard. Each time ROW BIRD started to move, there was a moment of quick acceleration, then heeling, followed by spray splashing over the gunwale. When I stopped to put another reef to the mainsail, I drifted toward half-submerged rocks. Setting the newly shortened sail again just in time, I slid away from the rocks.

The sound of water on the hull made it seem like ROW BIRD was rushing forward, but in the sloppy waters our actual speed was a crawl. Keeping the boat flat was the main thing on my mind, but after a few minutes, I realized that if I was going to make forward progress, I’d need more sail up, so I stopped and let a reef out. I hauled the main up again and while the chop persisted, this time there was almost no wind. Seconds later it reappeared, shot the boat forward and only by hiking out, something I never do in ROW BIRD, was I able to keep the rail out of the sea.

The winds were irregular but never entirely absent, so I usually rowed with the masts up, ready to take advantage of any breeze that might pipe up.

I had to concede that the water was too rough, so I abandoned Pender as my destination for the day. Portland Island was about 3 miles to the northwest, and I figured I’d find easier going in the sheltered coves on its south shore, so I steered for Princess Bay, the island’s biggest anchorage. Initially, I couldn’t see the ¼-mile-wide anchorage even though I was looking right where it should be, but as I got closer the islets that masked its entrance seemed to separate themselves from the island creating openings that had looked, just a few minutes earlier, like an unbroken wall. The water in the bay was still and flat, sunlight glinted off the smooth water, and crooked, weathered trees clung to the rocks at the edge of the bay.

I set my anchor and started cooking dinner. ROW BIRD’s cockpit is snug but the floorboards have room enough for my kitchen activities. Sitting cross-legged, I tended my camping stove, which I set near the centerboard trunk. I mixed couscous in a dried lentil soup mix, added water, slowly stirred and simmered it to a thick, mortar-like consistency. Then I turned the stove off, covered my concoction and waited until the pot cooled enough to hold in my bare hands. As I ate I was warmed by a small south-facing cliff that radiated the heat it had gathered from the day’s sunlight.

The anchorages at Portland Island range from open bays with sandy bottoms to steep, rock-bound coves. Ferries, like the one just coming into view at left, leave wakes known as “ferry wash” and can cause rolly conditions. It’s best to get the boat off the beach before the wake hits and, at night, to anchor with a stern line tied on shore to keep the bow facing the wakes.

The next morning I got up early to catch the flood tide toward the Penders, hopeful I’d reach the pair of islands this time. I put my drysuit on but the cool gray sky chilled me, and as I emerged from Princess Bay, a breeze from the southwest filled from behind. The tidal atlas indicated that a shift in the current’s direction lay ahead and I anticipated bumpy sailing.

Through my binoculars, I saw dark ripples in the water and low-lying rocks near the northwest edge of Moresby Island. Rounding the dark line a few minutes later, instead of the sailing getting gnarly, the wind abruptly died, and I took to the oars, leaving the sails up, and “motorsailed.” When smooth, leaden water between Moresby and Pender islands stretched as far as I could see, I dropped the sails and continued rowing. I set a course across 2 miles of open water toward the Penders and lost myself in the rhythm of the oars.

ROW BIRD handled the changeable spring conditions well, including calms, lumpy seas, and strong winds. The mizzen sail is a useful safety feature for heaving-to.

The pale rocky cliffs of North Pender shimmered in the tiny ripples around ROW BIRD as I drew near the island. Pigeon guillemots, soot-black but for white patches on their wings and comical cherry-red feet, came and went from their nests in the cliff’s hollows 50′ above me. Then, with a quarter mile left to go before making the entrance to Bedwell Harbour, a 2-1/2-mile-long inlet between the two islands, I felt myself being pushed back. An unanticipated current seemed to be pouring out of the harbor. The flood should have been flowing in by this point, pushing me into the harbor, but I was being moved south away from the island. I pulled hard on the oars to keep myself from being carried toward open water. I crept through the current and eventually glided into slower moving water on the opposite side of the mile-wide entrance.

I poked along the north shore of South Pender Island, weaving around huge boulders rising from the water—arranged as if they were in a Japanese stone garden—and skirting the towering hills that rose from a gray band of deeply fissured rock. The breeze was light and fluky, but after the hard pull on the oars, I couldn’t be troubled to row to the campground, so I raised the main and mizzen and sailed slowly up Bedwell Harbor.

The Beaumont campground by Skull Islet, like others in the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve with protected beaches and easy access to well-maintained tent sites and trails, are geared toward small boats.

I came ashore at the Beaumont campground on the shore of South Pender. ROW BIRD was the sole boat there; the whisper of the wind in the trees was interrupted only by the calls of birds. The beach was a shell midden, white with countless bleached fragments of shells that crunched underfoot.

After I set up my tent, I walked the steep Mount Norman trail. By the time I reached the 800′-high summit, the highest point on the Penders, my shirt was soaked in sweat despite the cool air. From an observation deck above the trees, I stared out at the islands below, tracing my route to the campground below and envisioning where I’d go next as I drew the scene in my sketchbook.

First Nations people in British Columbia still use parts of the National Park Reserve for traditional hunting and gathering and some areas, such as the burial ground on Skull Island (seen off the bow), are closed to the public as a sign of respect to the local tribes.

At dawn the next day, I sat on the shell beach looking over to Skull Islet, a round, 60-yard mound of slanted rock strata crowned with a dozen trees that was a burial site for First Nations people. The harbor waters were tranquil, but the weather radio predicted a strong storm two days out, and I knew I’d have to run for home or hunker down. I reviewed the tidal atlas to see where I could go with my remaining two days. Its arrows marked the flow of water through the islands that would push me north, south, or east—all the wrong direction—so I’d likely need both days to get safely back to the ramp at Sidney.

I spent the day at camp, and the following morning I headed homeward through the choppy waters of Haro Strait. Once I cleared the 2-mile ope- water crossing, I hugged the south shore of each of the Gulf Islands I came to. The intricate shorelines, rocky outcroppings, weather-worn shingled cottages, and meadowy pockets offered much more to see than the open water the shortest course would have taken me through. None of the islands—Moresby, Rum, Brethour, Domville, Forest—offered a good place to anchor for the night, so by late afternoon so I had decided to return to Sidney Spit for my final night.

The plip-plop of rain on my tent started slowly as the morning sky lightened. I sat on the floorboards, tidying up the cockpit, reluctant to don my raingear and head back to Sidney and bring an end to the trip. Low clouds blocked the sunrise. I eventually got underway and despite the drizzle, decided to loop around some of the islands closest to the town of Sidney before heading to the dock.

The Gulf Islands are in Vancouver Island’s rain shadow. While the west coast of Vancouver may receive more than 120″ of rain a year, the east side can receive less than 35″ annually.

ROW BIRD slid through the still, rain-flecked water as I rowed past the end of the spit. A half mile later the flag on my mizzen, a navy blue silhouette of a bird in flight on a white field, flickered about, so I set sail. As the wind grew, the hull started to hiss as it cut through the water. Close-hauled, I traveled past a cluster of rocky islets called the Little Group. When spray started to splash aboard and darker clouds approached from the south, I sensed that the full force of the predicted storm was coming. Soon, I had to feather the mainsail to handle the gusts as ROW BIRD bounced along parallel to the Sidney waterfront. I was in control for the moment, but I knew that with the rising wind, it was time to head in.

Two hours later, having put ROW BIRD on her trailer, I stood overlooking the cove where I spent my first night in Sidney. The flags along the edge of town snapped and blew straight back. Eastward, whitecaps covered the water between the shore and the nearest islands.

I ducked into a café for a cup of tea. As I flipped through my sketchbook, I paused at the drawing of the islands I’d made with pencil and pen, brush and watercolor at South Pender on the summit of Mount Norman. I had sailed the archipelago and now knew something of those islands, rocks, and coves. I’d traced their edges with ROW BIRD’s wake and filled the space within their outlines with my footsteps.![]()

Bruce Bateau, a regular contributor to Small Boats Monthly, sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at his web site, Terrapin Tales.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great trip in familiar waters, Bruce! Glad it worked out and thanks for telling us the tale.

I really enjoy reading accounts of trips such as this. Thank you for sharing.

Now that I’ve “swallowed the anchor ” I really enjoy these accounts. Keep them coming!!