Back in the ’60s, Roger Miller sang, “I’m a man of means by no means, king of the road.” My son Koen and I are men of means by no means, but we had an ambition to make the coast of British Columbia our road.

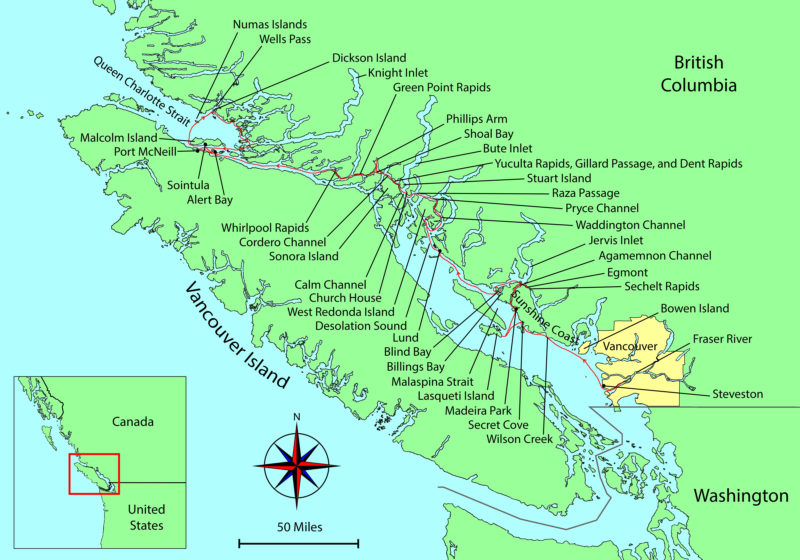

I had read and heard about the wondrous waters of British Columbia and long ago had my heart set on sailing them, so I proposed to Koen that we take a cruise. He studies math at the university in Vancouver and was doing quite well in his courses, so he could afford to take a semester off to join me. We looked into renting a boat or buying something cheap, but couldn’t find anything that would fit the bill. We shifted gears and decided we could build a simple boat in a month and still have enough of the summer left to head north along the mainland coast.

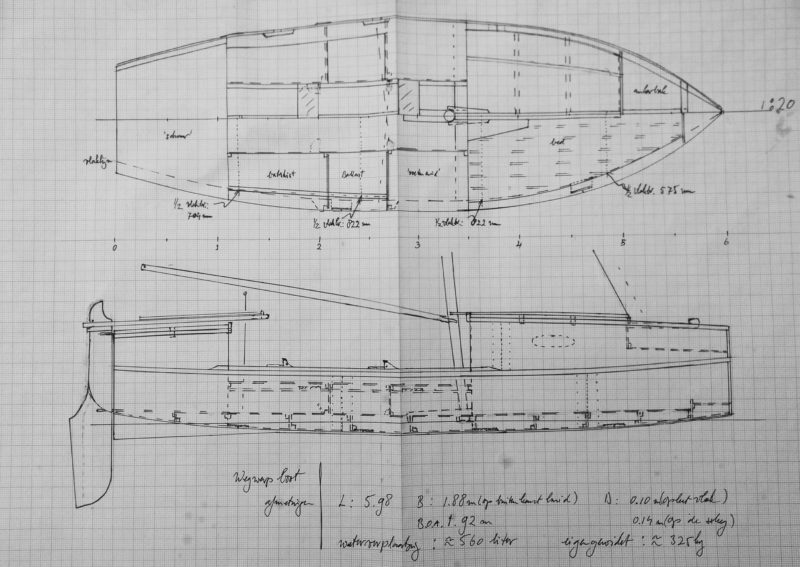

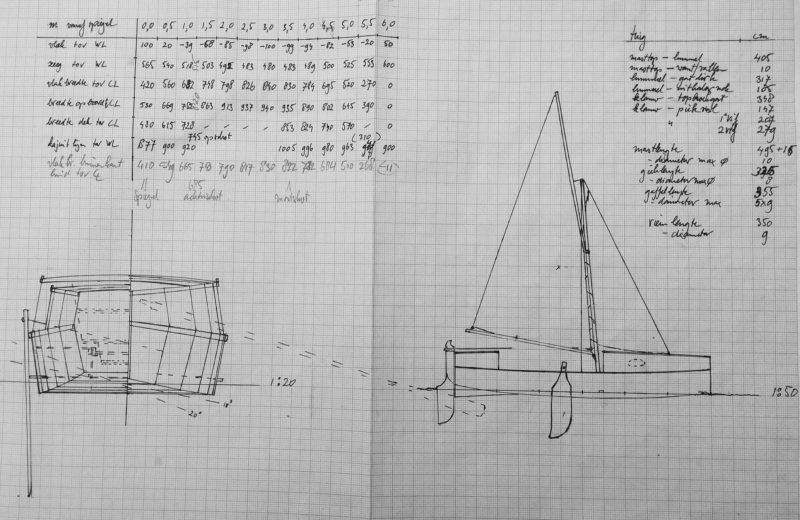

We let the idea ripen for a few weeks. It still felt good, so during lunch one day I grabbed a pencil and in a burst of inspiration sketched the simplest form I could think of. Most boats are designed to last for decades, but there was a time when people just hollowed out a log if they wanted to cross the swamps. On Lake Titicaca, people would bundle reeds and have a boat in short order. In other parts of the world people made birchbark canoes, coracles, or balsa rafts using the materials available to them. We’d do the same; in our case we had access to cheap plywood and construction lumber. And to outfit the boat for our voyage, the Vancouver area has no shortage of boatyards and chandlers, supermarkets, and secondhand stores.

We needed a place to build the boat, but Koen suggested that there were some things that didn’t lend themselves to preparation and we shouldn’t spoil the sense of adventure by having every last item planned in advance. I made my travel plans, and we would thereafter trust in chance. That became the beauty of building the boat as well as exploring the coast.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorKoen here is working on the storage compartments in the cockpit. The bottom, bulkheads, transom and foredeck were made with 5/8″ fir plywood and 3/8″ plywood used for the rest. The lumber for the building jig was later transformed into four oars.

I arrived in Vancouver early in April 2017, while Koen was still finishing his spring semester, and we made his room at the university our base camp. After I unpacked my drawing, the sails from my Ness Yawl, and some blocks, cleats, and ropes, I began the search for a place to build the boat. I walked the banks of Fraser River under a gray sky and peeked around big sheds, small shops, and seemingly deserted mini-marinas. I wasn’t finding many people around, but then someone yelled at me. A man alarmed by my snooping around by his trailer stopped me. I explained my intentions to him; he warmed up to me, introduced himself as Ken, and we shook hands. We parted and I continued strolling the waterfront. I hadn’t gone far when a car pulled to a stop next to me. It was Ken and he had chased me down to say his friend Alan could offer us his shop for a month. It was just the stroke of luck that our plan not to plan had allowed to happen.

With a building site secured, we ordered materials at a nearby lumberyard, and bought a saw, a square, and a small plane. The owner of the shop was so enthused by our project that he loaned us a circular saw, a jigsaw, and a straightedge.

We surprised ourselves by working seven days a week, finding it difficult to stop. We enjoyed taking bevels, chopping away at an oar or leeboard with an axe, or bending a rubbing strake, but we didn’t linger on the tasks or strive for a fine finish. The goal was to get the boat launched and use it. In four weeks, it was afloat, ready to sail, and fully loaded with provisions.

The boat was launched without ceremony or christening in the backwaters of the Fraser River. It floated high and had no leaks. The fisherman’s anchor had its place in a recessed part of the foredeck.

On Sunday, May 14, the forecast called for stable, sunny weather and light winds. We cast off and took to the oars. A yell came from the muddy banks—Alan was waving a last farewell. The ebb flowing down the Fraser River was in our favor, but the oars, each coarsely shaped out of 2×6, proved too long for good balance—so when a southwesterly breeze piped up, we tried sailing. We tacked slowly downriver. The tiller interfered with the mainsheet, so Koen pulled out a saw and cut the tiller to suitable length, all while keeping a steady course. Our pointed box, as rough as it was, was rising to meet our expectations.

The deep buzz of the city dwindled until there was little more than the occasional cry of a gull to be heard and we grew more aware of the murmur of waves and our own wake. Koen and I were quickly at ease with the boat and we adjusted sheets, shifted leeboards, and steered to the wind almost without thinking. Now and then we burst out in wild laughter—an indication, we realized, that we were tired and a bit nervous, but deeply satisfied with what we had accomplished so far.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

While the tide nudged us slowly past Steveston at the mouth of the Fraser, a fisherman aboard an aluminum skiff came by and hailed us. In our conversation, we told him about our adventure and learned he was heading out to tend some nets, a method of fishing allowed for First Nations people. He was taken aback by the boat’s diminutive size and the magnitude of our voyage, and surprised us by asking, “Have you obtained permission of the tribal elders to pass into our territory?” Without waiting for answer he laughed loud, opened the throttle, and sped away. The thought hadn’t occurred to us, and although the native fisherman was just giving us a good ribbing, it made us aware of another aspect of our whereabouts. Suddenly we felt a bit arrogant, as though we were trespassing like early explorers Cook, Vancouver, and Bodega y Quadra before us.

Later that day, with the city of Vancouver abeam as we headed north, a 4′ slab of styrofoam, carrying two masts and sails, crossed our track. This unassuming, unmanned craft had survived freighters, passenger ferries, and the shifting weather, keeping a steady northwesterly course. The little ketch was a reassuring sight and boosted our confidence.

The fo’c’s’le offered a comfortable refuge in the evenings. It was equipped with a bookshelf, a table, a wine and beer cellar, and two bunks.

The wind died slowly, and we rowed several hours in the darkening evening, growing ever more tired after a day at the heavy oars. With the help of a flashlight we found a mooring buoy in a small cove on the southeasterly tip of Bowen Island and tied our painter to it. We could hear the shore close by, but it was hard to see in the feeble light of our modest flashlight. An easterly breeze came straight into the cove and stirred the rig. I would have gone straight to bed, but Koen always has a healthy appetite, so he put a late dinner together. We finally crouched through the narrow opening to the “fo’c’s’le” and laid our tired bodies to rest. Koen was off to sleep in a minute, but for me it was an uneasy night worrying about the wind and waves.

On waking early I found the boat swaying and slamming in the waves in an uncomfortable way—the southeasterly had piped up considerably. I looked outside and in the morning light I could see the steep, rocky, wave-lashed shore just 100′ away. The marine forecast promised more wind from the southeast and a lot of rain, so we were eager to get away. Taking to the oars, we took up the fight against the wind and chop. The bow slammed back and forth; the rocks to leeward terrified us and made us row like madmen. We eventually managed to get far enough from the shore to stow the oars and hoist the sails.

We sailed closehauled along Bowen Island’s steep, wooded shore heading for Snug Cove, hoping it would live up to its name. We were over-canvassed, but reefing down wasn’t an option; any leeward drift while putting the reef in would push us dangerously close to the rugged coast. After 4 miles of anxious sailing we rounded the entrance to Snug Cove and found the marina inside so well protected that we had to row the last yards in the still air. We tied up to a floating dock, rigged a tarp, and let the rain come.

Soon after we had ducked out of the weather, a man approached in a boat and asked from under his dripping southwester what he could do for us. The nerve-wracking experience was probably showing on our faces; I blurted out, “A shower!” An hour later, after this kind man drove us across the island to home, Koen and I were washing away the sweat and grime. He and his wife also offered a beer, advice on not-to-be-missed spots, and some old charts as well. The tension in our shoulders slowly slipped away in the warmth of their hospitality.

When we rowed into Smuggler Cove, we heard the occupants a 21′ sloop anchored there say, “Well, here we have an even smaller boat!” As small as our boat might have appeared, it was big and heavy enough to make it unwieldy on shore. We had often wished we’d had a dinghy, something foldable, for more convenient access to land.

The following week, we crept along the Sunshine Coast and got acquainted with the scale of the British Columbia landscape, a tidal range approaching 16’, and an abundance of drifting logs and deadheads. We made an overnight stop at Wilson Creek and raided the town’s supermarket the next morning, stocking up on flour, oats, nuts, raisins, and powdered milk. Although our supplies were as simple as the boat itself, Koen saw to it that we would have a culinary high point every day. He had brought his sourdough starter; it was so dear to him that it even had a name: Jesaja. In the morning, the sweet smell of fresh bread filled the air; Koen was beaming at what he had created in our two frying pans.

I had been wondering why almost all of the boats in the area had dodgers and awnings, and got my answer on our 9-mile crossing from Secret Cove on the mainland to Squitty Bay on the southern tip of Lasqueti Island. The air was cool so we sat in the blazing sun to keep warm. By the time we reached Lasqueti we were well cooked.

We dropped the sails and rowed into a 30-yard-wide natural harbor under the watchful eye of a perched bald eagle. We tied up at the government dock, and when the harbormaster came down, we paid her the fee for us to stay the night. We asked her about drinking water, and she told us that people on Lasqueti live off the grid and provide their own power and water. She directed us to a man living nearby who would be able to fill our 15-liter canister. We met him standing on the float beside a beautiful 23′ sloop, and found out he had built this gem of a boat of mostly driftwood from that very beach. He had milled it with a chainsaw and worked it with hand tools. The water running from his tap at his house was like tea, colored by cedar trees, but he declared it was good drinking water.

After a few days of exploring Lasqueti and nearby Jedediah Island, we recrossed Malaspina Strait back to the mainland, rowing in a dead calm a dozen miles eastward to spend the night at Madeira Park. We were used to sailing Europe’s coastal waters around the North Sea, where the tidal range is around 8’, and were eager to see what tides twice that do in the many rapids of the B.C. coast. What we’d heard about Sechelt Rapids sounded like something almost from a different planet. We sailed and rowed north then east along the half-mile-wide Agamemnon Channel into the mountain-fringed waters of Jervis Inlet and moored at the small town of Egmont.

The next day we hiked to the Sechelt Rapids along a footpath through a lush cedar forest. We’d had several warm, sunny days and it was nice to stretch our legs in the cool shadows of the woods. Beyond the trees that surrounded us, we heard a muted rumble that grew louder as we got closer. Quite suddenly we were at a barren rocky patch just a few feet from the rapids. From the southeast, millions of gallons swept across our overwhelming panoramic view racing to the northwest at bewildering speed. The ebb-powered current piled standing waves up against small islets as if trying to push them out of the way. At the tip of one, water cascaded down 6′ into a chain of deep, ever-widening whirlpools.

We sat there in amazement for almost an hour, as the hissing and roaring rapids accelerated to 17 knots on the spring tide. If this was what the British Columbia rapids looked like, how could we even consider taking our boat through those that lay ahead of us? From far upstream, an aluminum crab boat was bearing down on the rapid. Weaving and swaying, it skirted the worst turbulence as it sped downstream. The skipper leaned half out of his window and waved to us. That broke the spell, and we came to our senses again. Koen and I started walking back along the trail, discussing our possibilities. The current in each rapid changes direction four times a day, and we’d have windows with little or no current. We ended up with the feeling that we stood a good chance getting through any of the rapids that lay ahead.

Koen was a picture of concentration as we raced wing on wing with a reefed main along Malaspina Strait. We initially used an oar as a whisker pole to hold the jib out for downwind runs, but later found a piece of driftwood to do the job.

Two days later we were again on our way back to Malaspina Strait. The weather had changed; during the night a southeasterly had swept through, bringing wind and rain squalls. We set out from an anchorage in Ballet Bay on the south shore of Blind Bay, and the water grew more exposed. We needed to reduce sail. Tucked in the lee behind a small island, we put two reefs in the main and struck the jib. Koen and I decided to head back out into the Strait and test the boat and ourselves. If something didn’t feel right we would turn around, seek shelter, and wait for better weather.

We got hit by a few gusts, but everything seemed under control. Out in the Strait we jibed and set a course back into the protection of Blind Bay. I asked Koen what his gut feelings were, and he thought we just could continue sailing north along the Strait. I was a bit more hesitant, but there were many places where we could take refuge. Koen steered out of the bay again. It was our first sail in more than a gentle breeze, and we felt comfortable on a downwind run. We raised the jib opposite the main and used an oar as a whisker pole to spread the jib out to better balance the main and ease the pressure on the helm.

We were making good speed when suddenly a scraping and rumbling resonated in the hull, and then there was a strong jerk at the tiller. At first we were worried that the boat was breaking up, but it soon dawned on us that we had run over one of those logs that float so low in the water that they are almost impossible to see in the waves. It slipped astern; the boat was intact. The collision and the day’s gray skies didn’t keep us from enjoying the sailing. The boat really moved well. By the time we sailed into Lund we had covered 30 sea-miles in 6 hours, not bad for an ugly duckling.

After an overnight stay in Lund we sailed to Desolation Sound. Our plan to proceed without a fixed plan left me and Koen to decide on our strategy for the coming days and weeks. To the north, two deep inlets—Bute Inlet, 43 miles long, and Knight Inlet, 67 miles—promised hidden jewels of nature well inland, but we didn’t like the prospect of long days of rowing the steep and likely windless fjords. To the west, the route through the islands clustered between the mainland and Vancouver Island would lead us through several rapids. The neap tides were upon us, so we would traverse the rapids at their least dangerous and could safely make our way to the Broughton Archipelago. Cruising in the rather gloomy Desolation Sound left us wanting to see the horizon again, and the prospect of sailing along the islands on edge of Queen Charlotte Strait appealed to us.

We anchored in the still waters of Roscoe Bay on West Redonda Island. We were lured by the promise of a short walk along a trial to Black Lake where we could bathe in fresh water. The walk turned out to be 20 minutes of bushwhacking.

From our anchorage in the still waters of Roscoe Bay on West Redonda Island, we had a magical tailwind following us north along Waddington Channel, west along Pryce Channel, through a U-turn to the south in Raza Passage, and giving as a final push northward on Calm Channel.

We spent a short and uneasy night anchored by the spooky, and apparently deserted, village of Church House.

Underway again, we steered for the gap between Sonora Island and Stuart Island, where Yuculta Rapids was hiding just around the corner, followed close behind by Gillard Passage and Dent Rapids. We had left in good time and were carried by a fresh southeasterly under sunny skies, putting us two hours ahead of the slack water. We had studied the charts together and decided we would hug the shore to starboard first, then cross and hug the shore on the other side, to avoid the worst and possibly even get some back-eddies to help us through. We entered sailing the jib only, and yet had just enough speed against the 2- to 3-knot south-going current.

We had to wait for the tide to rise for us to cross a shallow spot in Cramer Passage at Broughton Island, so Koen passed the time doing some solo sailing.

Just as we proceeded to cross to the port shore, two bald eagles gave alarming shrieks and flew over us, startling us. There were some tide rips, but they were easily managed and our transit of the rapids worked out much better than we had feared. In less than half an hour we had passed Yuculta and were still hugging the shore to port.

To avoid the rapids in Gillard Passage, we tried the narrow opening south of Inner Passage. While a few dozen sea lions watched us from barren Sea Lion Rock, we hoisted the mainsail to power up. We had to perform a tight turn to port against 3 or 4 knots of current working against us in a channel less than 30’ wide. We succeeded in the turning but failed to make progress: we had to slip out the main’s reefs while being set back in the direction of Sea Lion Rock. We did it in record time, and began to make progress against the current again. Keeping close to the lee shore gave us the most wind and the least current. Carefully, we steered just clear of the boulders underwater and tree branches overhead; a fortunate gust or two helped us inch to wider waters.

By the time we arrived at Dent Rapids a mile and a half farther along, the turning of the tide was near. We sailed close to Dent and Little Dent islands against the last bit of flood entering the wide Cordero Channel. Koen and I felt victorious, and to celebrate we decided to put in for a break at Shoal Bay, just 7 miles from Dent .

The 600′-long wooden pier loomed 20′ above us while we tied up at the floating dock. We strolled down the pier, which connected to a wide valley. Six cottages and a vegetable garden occupied the land where there had once been a thriving town with 5,000 inhabitants.

A driftwood log (at the left) crept by very slowly and paid us a visit behind Gilford Island near Thompson Sound. We were moored in a tiny shallow cove, with lines to shore off the bow and stern holding us just off a tiny beach.

The next afternoon, we rowed and sailed in light air north from Shoal Bay into Phillips Arm. Five miles in, the wooded hillside was fronted by a grassy foreshore. From a distance, we could see a brown spot slowly working along the shore. We hesitated on how close to get. Can grizzlies swim fast enough to get to us? We kept a good 70 yards away and soon saw a second, lighter-colored bear. They were both eating grass and sounded just like grazing cows. We rowed to a pair of anchored logs, tied the boat alongside, and continued to watched the sow and her large cub grazing while we prepared dinner The two bears finally meet in a mock battle, towering high on their hind legs. The cold air dropping down from the snowy slopes far above made us seek refuge in the fo’c’s’le when the light faded. The bears disappeared in the woods. We closed the hatches in case they changed their minds and wanted dessert.

We let the boat dry out in Potts Lagoon and were surprised to see the receding water reveal a bear’s paw print just beside the boat. The boat’s flat bottom made it easy to wait aboard the boat for the next tide.

We easily negotiated the last two rapids, Green Point and Whirlpool, thanks to the neap tides of the quarter moon. The moderate southeasterly breezes of these days suited us well, and before long we arrived at Port McNeill on the Vancouver Island shore. It was a dull place, but had a convenient harbor and shops. From there we went on to the island towns of Alert Bay and Sointula.

From the outset, I had been dreaming of sailing farther north, but we decided not to. Instead we chose to explore the close-by islands during the remaining three weeks. The Broughton Archipelago offered a myriad of islands and islets, and the open waters of Queen Charlotte Strait were never far off. Leaving Sointula, we rounded the red-topped lighthouse at Pulteney Point on Malcolm Island, and half sailed, half rowed in a dwindling westerly breeze. Looking north across Queen Charlotte we saw the snow-capped mountains of the Coast Range. Would we tempt fate and row across the 11 miles to the mainland shore in the sunny calm? It was early enough in the day to say yes, so we set to work. But after a quarter of an hour, a light breeze brushed our cheeks, and with relief we laid the oars aside and set sail.

A First Nations woman had recommended we keep an eye out for trade beads, the trading currency that dated back to the voyages of Cook and Vancouver. I found one on the beach here near the site of Mamalilaculla on Village Island.

Within 20 minutes the northwesterly became a fresh breeze. The mirror-like water was soon fractured and began to build up in small seas, each with a glassy green crest. The waves threatened to board us, but our rough-and-tough plywood box answered by dancing elegantly from one peak to the next. Just over halfway across the Strait, the Numas Islands offered shelter to put in a reef and continue north across the open water to the north being a bit more relaxed. As we approached the mainland, we could shake out the reef and carry on under full sail. Soon we glided into Wells Passage. The low sun gave the shoreline a tranquilizing golden glow, and we coasted into a bay on the north side of Dickson Island to drop the anchor for the night.

The diversity of Broughton’s islands made for interesting adventures. Sometimes we would hide from high winds in a small cove or deep in a fjord, then in lighter conditions we would venture out into the Strait. We squeaked through the narrow entrance of a lagoon, and a small family of curious Pacific white-sided dolphins appeared under the bow. In another lagoon we let the boat dry out on an ebb, only to find bear prints just beside the boat when the falling tide revealed them. We anchored off a deserted First Nations village where a frame made of three immense logs was all that remained of what must have been an immense longhouse. Crossing the entrance to Knight Inlet, we heard a loud hmpfffff as a fin whale rose less than 100’ away to take a breath.

The boat had served us well in the two months we’d been sailing. It would have deserved to have a name painted on the transom, but we never did a proper christening. The boat was as unfinished as the trip was unplanned, and both had their practicality and their charm. It was not a disaster for the rough plywood hull to bounce over a half-submerged log any more than it was a loss of progress to wander aimlessly from our northern course.

The boat was a temporary vehicle meant to satisfy our urge for a summer’s travel. At the beginning, we thought we might leave the boat on a beach or set it on fire when we were done with it, but we began to wonder if it could brighten someone’s life when it was time for us to return home. At Port McNeill, we met a fishing guide who lived with his wife and two small kids, working their float-house fishing lodge in Cramer Passage in the summer. We offered the boat to them, thinking it could be a nice distraction for the kids since they had no nearby neighbors to play with. We were as happy as they were that our boxy boat would have a new home after having served us so loyally, and were met with grateful tears when we delivered it.

Koen and I returned to Vancouver by bus and ferry. Back home, in the midst of telling my daughter about the adventures I’d had with her brother, she grabbed me and insisted that she and I have a new experience for the two of us sometime in the future. I replied with a smile, “How could I say no to that?”![]()

Hein van Greevenbroek is a carpenter and a builder of furniture boats who is currently living in the Hardanger region on the west coast of Norway. He emigrated from The Netherlands 12 years ago on a 49′ catamaran he designed and built. He has done most of his sailing on traditional boats in Holland’s inland waters, but has done some seafaring as a mate on schooners and smacks. He once owned a 66’ tjalk (a type of Dutch sailing barge) which he operated as charter vessel, has worked at several boatyards in Holland and Norway, and sailed his Åfjord square-rigged halvfjerrømming from Trondheim to Amsterdam. He hates engine noise.

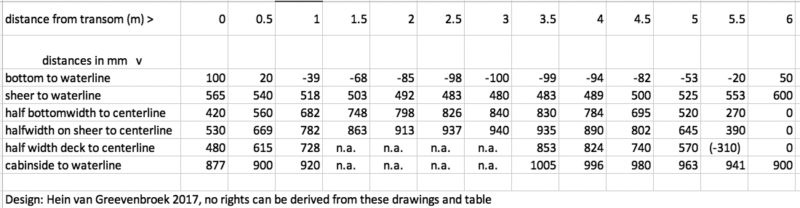

In response to a reader’s request for plans for the boat, QUICK AND DIRTY, Hein provided these drawings and offsets:

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

She’s a lot like my Dovekie…neat boat

Sounds like a great trip. It’s one that will be remembered for years to come.

Good story of a great trip! You’ve proved yet again that the barrier to entry (monetarily at least) is not that high for a grand adventure on the water.

Brings back memories of our trip last year in those same waters.

Thanks!

What a privilege to be able to share such an adventure with your son.

I loved the video. It was a wonderful way to share your experience sailing the boat, as well as viewing the unexpected, but delightful, bear scene!

Thank you for sharing your experiences! I appreciate it. I hope to have some free time to be able to sail again.

Hallo Hein, Koen,

Een droom verwezenlijkt door vader & zoon. Een toepasselijke naam voor het bootje zou kunnen zijn: Heilig Geestje. Ik heb genoten van jullie logboek en video, jammer dat er geen timelapse van het bouwen bestaat. Graag bij het volgende project meeleveren. Wordt dat misschien een glider o.i.d.? Met je dochter zwevend van Norge naar NL. Ik hoop dat de nieuwe eigenaars het zeilkistje zo koesteren zodat misschien je kleinkinders ooit nog eens een tochtje ermee weten te maken. Of dat het nog eens op de HISWA in NL te zien is……Ik voel een diep respect voor je ondernemen met hem, chapeau! Lieve groet, Mathieu Hendriksen

online translation:

A dream accomplished by father & son. An appropriate name for the boat could be: HOLY SPIRIT. I enjoyed your log and video, too bad there is no time-lapse of building. Please contribute to the next project. Is that perhaps a glider? With your daughter floating from Norway to the Netherlands. I hope that the new owners cherish the sailing box so that maybe your grandchildren can ever make a trip with it. Or that it can be seen at the HISWA in the Netherlands. I feel a deep respect for your business with him, chapeau! Kind regards, Mathieu Hendriksen

Excellent adventure! Great boat! Any plans available?

Hey John, sorry for very late reply. Yes, plans available, for free. Interested?

Hein provided drawings and offsets, now included following the article. Click on each to see a larger version of the image.

Editor

J D I

Hoi Koen en Hein,

Inderdaad fantastisch wat jullie samen gedaan hebben. De tijd nemen, samen een schip bouwen en vooral ook de tijd voor elkaar hebben. Iets om je hele leven te koesteren.

Groetjes vanaf die 66′ tjalk!

Jan

Online translation:

Hi Koen and Hein,

Indeed fantastic what you have done together. Taking the time, building a ship together and above all having the time for each other. Something to cherish your whole life.

Greetings from those of 66 tjalk!

Jan

Great looking boxy Bolger-style boat! Even has a mini aft cabin!

Dear friends,

Please,if possible some send me the drawings or plans

Thanks so much

Congratulations, my friend

I would like to get a drawing or plans for me to build it model here in my country, Brazil.

Thanks to much.

I love this story!! Of course we all hope the boat we build will be lovely and admired, but the fact is that it is the crew that has the adventure, and the boat is but a means. It is, as Pete Culler was fond of saying, just a boat.

Wonderful story, wonderful trip. Thanks for sharing it and providing details of the boat. I wonder, given your daughter’s request, is there a sequel?

I had stayed in touch with Hein after working with him on this story and last year asked if there would be a story about the father-daughter cruise he had mentioned. Unfortunately, he was undergoing treatment for cancer at that time. I learned just last week that he had passed away in April.

—Editor