Will Stirling’s 15’ Sailing Dinghy has a shape that emerged gradually over a period of 15 years. He built his first dinghy in 2002, while he was in Cornwall working for Working Sail, a boatyard that builds pilot cutters. In his time off from building cutters, most of them over 40’ long, he decided to build a boat (just for a change!) and, constrained by the size of the small bedroom/workshop he inhabited at the time, settled on the 7’10” Auk designed by Iain Oughtred.

That dinghy, built of larch on oak, ended up as the tender to EZRA, one of the pilot cutters built at Working Sail. Stirling reshaped the design of the Auk to create his own 9’ lapstrake dinghy and so started a process of refinement—adjusting the shape of the transom, the stem, the sheer, and even the number of planks—that homed in on a hull shape he was satisfied with. By 2004 he had built four dinghies, and six years later he was producing a steady stream of dinghies, ranging from 9’ to 14’ long. He’s currently building his 38th dinghy.

It wasn’t until he had built 14 or 15 of the small boats that he was happy enough with the shape to commit it to paper as a set of lines, the first of what is now a range of six dinghies available as plans from Will’s company, Stirling & Son, in Devon, England.

When it came to building a boat for himself for coastal voyaging in 2012, he naturally chose what was then the biggest boat in his range, the 14’ Sailing Dinghy, and adapted it for adventure sailing. It was on that boat that he made the first two voyages of his slightly madcap project of sailing around every offshore lighthouse in Britain. A potentially dangerous incident (a near-capsize too complicated to explain here) during a 120-mile offshore trip from Devon to the Channel Islands and back, however, convinced him he needed something a bit more seaworthy.

Will Stirling

Will StirlingThe Stirling dinghies are all built of mahogany on oak and are copper riveted.

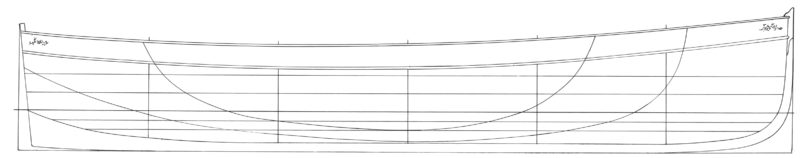

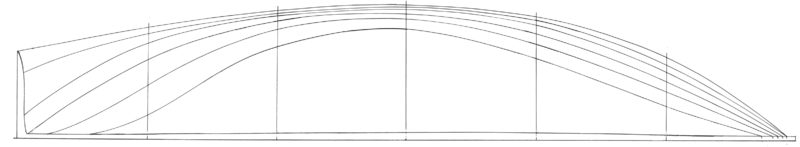

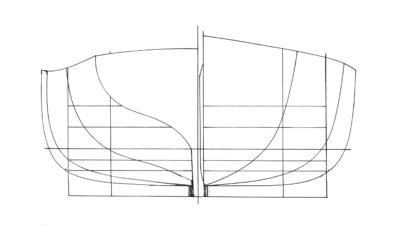

The 15’ Sailing Dinghy was born by simply spacing the molds of the 14’ dinghy apart an extra inch per foot. The main changes were an extension to the foredeck and the addition of side decks and a deck aft with a coaming around the cockpit to keep the water out. The longer foredeck allows someone to sleep under it without getting a shot of spray in the face. The 15-footer also has a slightly stronger sheer. Like most of Stirling’s dinghies, it is varnished on the outside and oiled inside.

Will Stirling

Will StirlingThe rudder blade is weighted with disks cut from lead sash weights. Hammering the lead spreads it out to cover the beveled edges of the hole, locking the lead in place.

Well-thought-out details abound in the 15-footer; some are purely decorative, others extremely practical. The sheerstrake has an elegant, gold-leafed cove; the thwarts have nice decorative beads scribed into their bottom edges. The dinghy also has some special features to fit its role as expedition boat, such as the enclosed centerboard case, which prevents water flooding into the boat in case of capsize. The plate-brass centerboard will drop when the uphaul is released, but it is fitted with a downhaul in case stones jam in the board and prevent gravity from doing its job. There is even a short length of line, which Stirling calls a “pig’s tail,” secured to the lower aft corner of the centerboard so it can be pulled out of the slot from beneath the hull if all else fails.

Will Stirling

Will StirlingThe sheer strake is protected above and below and decorated with gold leaf coves and carvings.

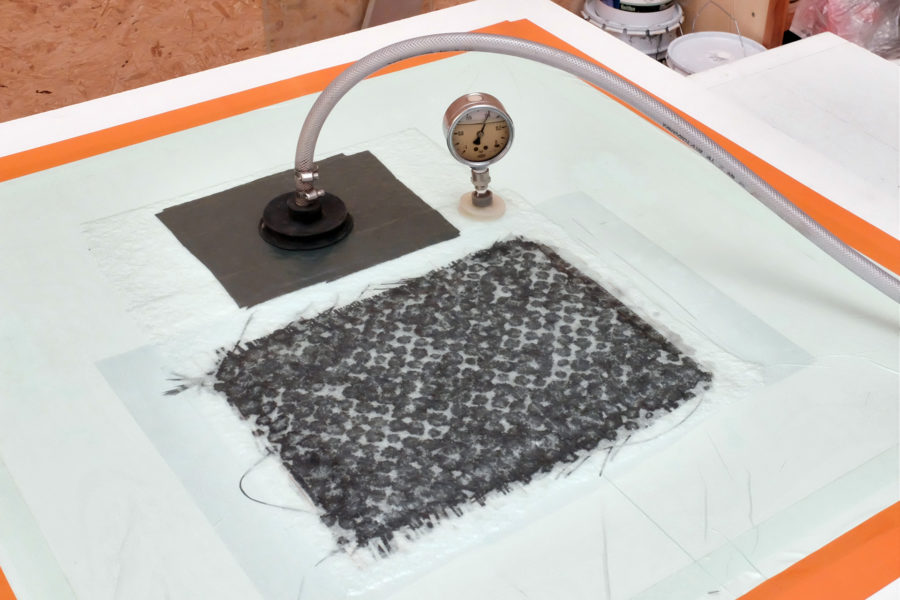

For planking, Stirling long ago abandoned larch in favor of mahogany (Khaya ivorensis, FSC-certified). To keep the garboard from cupping, small wedges are inserted between the plank and the steam-bent frames, and riveted through to hold them in place. It takes about 2,000 copper rivets to build the boat, with three rivets per foot on each of the planks holding the laps together and the frames to the planks. The plank ends are triple-fastened with bronze nails.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonThe dinghy’s bottom has brass half-oval along the keel and bilge guards to protect the hull on the beach.

The boat I sailed, christened GRACE after Stirling’s seven-year-old daughter, had been out of the water for nearly two years before we launched her at the end of this past summer, yet she only took on a wee bit of water before the planks swelled up and she was watertight again. She certainly made a pretty sight, bobbing at her anchor in Sennen, Cornwall, with her balanced lug sail set. Weighing in at almost 500 lbs, she’s not the lightest boat, and while it was easy enough for the two of us to drag her across the 30’ strip of sand from the stone slipway down into the sea, we were glad to have help with her recovery eight hours later, by which time the strip of sand had tripled in size. But lightness is not necessarily what you are looking for in a small boat intended for big voyages, and this boat is built to last.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonCast bronze outriggers add 18″ to the span between locks.

There was a light westerly breeze and a confused sea as we headed out of Sennen, but GRACE cleared the off-lying rocks without any fuss and we were soon in the open sea making good, if not spectacular, progress. GRACE has a burdensome hull well suited to her role as expedition boat, but that doesn’t mean she’s slow. Stirling has combined a full ’midship section with moderately fine bow and a nicely tucked-up transom—a hull form that slips along very nicely indeed.

Stirling opted for a balanced lug rig, which performs excellently on every point of sail except close-hauled. The boat slowed down whenever we tried to pinch her up into the wind, and took off as soon as we eased off onto a more comfortable angle. It was probably no better or worse than on many traditionally rigged boats, where it’s usually better to opt for the extra speed rather than try to claw an extra few degrees upwind. Once she was sailing at a sensible 45 degrees or so to the wind, GRACE was unfailingly steady and, well, graceful.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonA half jaw is used instead of a parrel to keep the boom tight to the mast.

Even though we were only sailing 8 miles offshore and the wind was never more than moderate, mostly 4 to 6 knots rather than the forecast 7 to 10 knots, I was grateful for the extra protection provided by the side decks and cockpit coaming. The only slight drawback is that, when seated inside the cockpit, you can’t lean out as much as you would on a completely open dinghy. You soon get used to this, however, and when the boat does heel over you can sit out on the rail and take advantage of the extra comfort provided by the side decks.

On the longer journeys this expedition dinghy is intended for, you can’t always rely on having continuous wind, so it’s important the boat rows well. Stirling fitted a pair of custom-made bronze outriggers, which were bolted through the side decks and extended the rowlocks a good 9” outboard of the hull. The arrangement was fine when I rowed the boat in flat water but awkward in a seaway when the oar blades tended to catch the waves and the looms chafed the top of the coamings. Stirling has since added a pair of collars around the rowlock shafts which should raise the oars enough to clear the coamings and the water.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonThe dinghy’s deck keeps spray out on rough passages and is wide enough to sit on to get some weight on the weather rail when the wind has piped up.

GRACE proved a pleasure to row, even against the strong contrary current we encountered at one point. I’m a sucker for rowing and will happily row at my own slow but steady pace for hours on end, but if you’re looking for a dinghy that you’ll mainly row, there are other boats that will be more nimble under oars. One obvious use for Stirling’s expedition dinghy is for so-called “raids.” The boat is both seaworthy and fast enough with two people on board to do very well in the events.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonThe balanced lug sail is made of Clipper Canvas, a stable fabric woven of spun polyester designed to look and feel like canvas.

GRACE was sold just a few weeks after I sailed her and packed off to some superyacht in Mallorca to start a new life in the Mediterranean. Whatever use any of the Stirling dinghies are put to, it’s a comforting thought to know they will almost certainly end up as someone’s family heirloom, with owners decades down the line appreciating their handsome design and solid construction.![]()

Nic Compton is a freelance writer and photographer who grew up sailing dinghies in Greece. He has written about boats and the sea for more than 20 years and has published 12 nautical books, including a biography of the designer Iain Oughtred. He currently lives on the River Dart in Devon, U.K.

15′ Sailing Dinghy Particulars

[table]

Length/15′

Beam/5′2″

Draft, board up/8.75″

Draft, board down/32″

Sail area/130 sq ft

[/table]

The 15′ Sailing Dinghy is a stretched version of Stirling’s 14′ Sailing Dinghy (lines shown here).

The 15’ Sailing Dinghy is available as a finished boat from Stirling & Son. The company also offers plans for some of their other sailing and rowing dinghies, including the 14′ Sailing Dinghy that preceded the 15′ Sailing Dinghy.

Excellent boat. The details are fascinating and impeccable. I’d be very happy to know a source for enclosed bronze rowlocks (oarlocks), as I’m suddenly having trouble keeping one of my oars in its open oarlock.

You can order them at Chesapeake Light Craft

I like the balance-lug sail. I had one some 40 or so years ago on an open centre board skiff of about 12′ long. Worked well.