One day in the early 1990s, a local contractor visited my boatbuilding shop in Marblehead, Massachusetts, telling me he’d been hired to convert an old boatshop into a playhouse. “The museums and antique dealers have been through it,” he said; “take anything you want or itʼs going to the dump.” The shop had been run by Samuel Brown, an MIT-trained naval architect, and his brother Bill, a boatbuilder.

The building was mostly empty but there were two steamboxes and a wood-fired stove for their boiler. I took those. In the long back room there was a planking bench with odd parts scattered around. Above the bench, tucked under the eave, the blackened end of a tight roll of paper caught my eye. I took the roll down, dusted it off, and put it in the truck. I loaded everything else that looked useful and drove off. That evening, I unrolled my find.

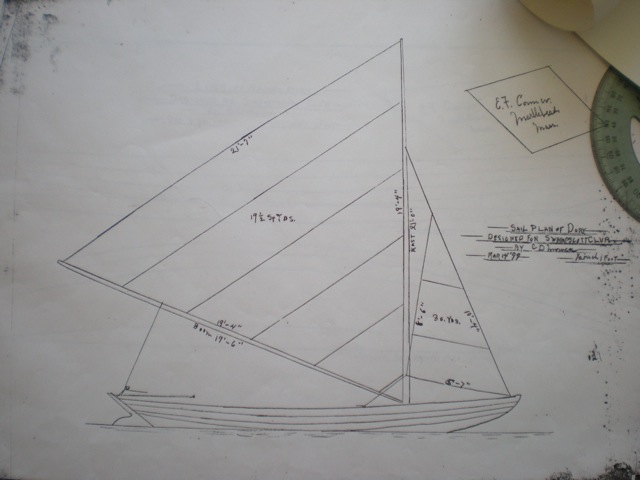

The roll was three sheets of drafting linen with edges black and ragged from years of dust and smoke. Pencil-drawn designs were inscribed “Lines Plan, Construction Plan, and Sail Plan,” for “Racing Dory designed for Swampscott Club,” signed C. D. Mower, each with their separate dates, 16 and 18 December, 1898, and March 14, 1899. I knew the Mower name, mostly from R-boats and New Jersey catboats of his design. This plan was old, but beautiful, interesting, and very racy. I had to find out more.

I visited Peter Vermilya, small-craft curator for Mystic Seaport Museum. He retrieved a February 1900 article on the design from The Rudder. The pencil drawings were virtually identical with the inked drawings in the article. Charles Drown Mower was a native of the Boston area, and had worked with Arthur Binney and then B. B. Crowninshield. He had become the design editor for The Rudder in the summer of 1899 and this design was believed to be his first commissioned design. Peter’s first remark on seeing the drawings was “Now you have to build one!”

All photographs courtesy of the author

All photographs courtesy of the authorThe lack of decks on the dory helped determine where it fit in among the racing dories of its day.

I later made my way to the Swampscott Club in Swampscott, Massachusetts. There I found pictures of these dories racing and club members who knew their history. They told me that after the first year, these dories were decked over and concluded the plans I’d found were for the “X-Dory.”

Lee Van Gemert, a former national champion in the Indian Class, also saw the drawings and said “Thatʼs where the Indian came from. ” In 1921 people from the Massachusetts Yacht Racing Association had gone to yacht designer John Alden asking for a children’s boat like Mower’s dory. William Chamberlain, a Marblehead boatbuilder, built six boats but the Indian was never really a kid’s boat and at the end of the first summer they were all put up for sale and bought by people from Boston’s South Shore. The Indian then became the largest class in Massachusetts Bay. Sam Crocker, working for Alden, gave the Indian a broad transom and a skeg-hung rudder, but the hull shows its connection to the Mower dory. The Indian carries a big marconi rig and calls for 350 lbs inside ballast.

The Rudder index put together by Mystic Seaport showed another 21′ Mower Dory design from 1911. This turned out to be an update of the 1898 design, this time for Massachusetts Bay. The changes were minimal, with a very slight chine added in the middle of the earlier wide garboard, a rectangular centerboard, and other alterations to make the design easier to build. Matt Murphyʼs book Glass Plates & Wooden Boats incudes Willard Jackson photographs from 1903 and 1907 showing X-Dories decked and rigged with shrouds, and sailing often with four people aboard. I have since found one undated Jackson photograph of an undecked boat sailing off Marblehead.

Suzanne Leahy, a Cape Cod boatbuilder who grew up in Marblehead, saw the drawings and mentioned a similarity to the Beachcomber, William Chamberlain’s 21′ racing dory. In Building Classic Small Craft John Gardner noted that the Beachcomber was a popular racing class until 1913 when a young Sam Brown designed OUTLAW, a similar dory with a flatter sheer and better speed. Sam Brown’s archive is in the collection of the Peabody-Essex Museum in nearby Salem, Massachusetts. Curator Dan Fenimore found the plans for OUTLAW among Brown’s papers. OUTLAW looked a lot more like the Mower than a Chamberlain suggesting that Sam Brown had these very Mower drawings when he designed OUTLAW. It’s likely he had rolled the drawings, then tucked them over the planking bench where they sat for 77 years.

The garboards are built up of three planks joined with flush dory bevels and rivets. The seams between them are visible here with one running out at the transom and the other at the garboard’s upper edge. To the far left is one of the butt blocks on the broad strake.

Building the Mower dory took place over a couple of years. I set up a long shrinkwrap-covered wigwam with bent saplings and in it built the hull during one winter. I lofted the boat and then began work with sawn white-oak frame halves joined with rivets, a white-oak stem, and a white-pine transom.

A single 26″ wide white-pine board became the bottom. I cut it to shape with the circular saw set at its maximum angle and still had plenty of planing to do for the bevels that receive the garboards: The shallow deadrise required 6″-wide bevels through the boat’s middle. For the garboards I had a few Atlantic white-cedar boards that had the length but not the width I needed, so I built up each garboard from three planks joined with flush dory laps riveted together. The broad and binder strakes are Maine white cedar, butt-blocked to get the length and shape. Both the port and starboard planks for the sheerstrake were cut from a single 26′-long white pine board. The strakes are dory-lapped with 45-degree bevels on the tops of the plank, rolling bevels on the bottom edges of joining planks, and rivets every 3″. In between the sawn frames are pairs of steam-bent white oak ribs riveted in place.

Raising the mast is made easier by a hinged partner and a ramp to guide the foot of the mast to the step.

The breasthook and quarter knees were cut from hackmatack crooks. The inwales are bent in place and screwed to the sheer strakes. For the two rowing stations, butternut pads on the rails are drilled for tholepins. The butternut thwarts sit on yellow pine risers and are braced with hackmatack knees. I made the centerboard rectangular—like the 1911 update and even more like the Indian. It’s a 17″-wide piece of African hardwood with a ¾″ square brass rod on its leading edge. The centerboard trunk has 2″ x 12″ white oak logs riveted to white oak head ledges secured to the bottom board with hanger bolts. To make it easier to step the mast I used hinged mast partner of an old whaleboat design. The mast step is a 3″ thick chunk of oak with a big knot drilled out.

The white oak rudder has gudgeons that slide down a single long transom-mounted pintle. The top of the pintle gets lashed into a groove set near the transom top.

The flat sheer of the Mower dory distinguishes it from the Beachcomber class that preceded it.

The 21′ mast is solid, rounded out of glued-up 2″ Sitka spruce. The 20′ boom is also Sitka. Every bit of wood got multiple coats of raw linseed oil before and after installation. The interior has boiled linseed oil for a finish, the exterior has Swedish linseed oil paint, the bottom antifouling paint over red lead. I sewed the 27-sq-ft jib and the 175-sq-ft leg o’ mutton main. It was time to put Mowerʼs lost design to the test.

The dory proved herself well sailing in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Maine. The strongest breeze I’ve encountered, about 15 knots, was off the WoodenBoat waterfront at Brooklin and the dory was well balanced and exciting. I found her remarkably stiff when moving about the boat at rest or keeping her upright in a breeze, and she moves very easily under either sail or oars.

The dory proved herself well sailing in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Maine. The strongest breeze I’ve encountered, about 15 knots, was off the WoodenBoat waterfront at Brooklin and the dory was well balanced and exciting. I found her remarkably stiff when moving about the boat at rest or keeping her upright in a breeze, and she moves very easily under either sail or oars.

An article in a 1900 issue of The Rudder reported that “the [Swampscott] Club had a fleet of about 10 boats, which were raced throughout the season, and a great deal of sport was had, as the boats turned out very satisfactorily and proved their ability to whip everything in a good breeze…. Their strong point was their ability to go to windward, while their quickness in stays and ability to lug sail were also noticeable points in their behavior.” Over a century later, all this remains true.![]()

Thad Danielson restores, builds, and designs classic wooden boats for sail oar and power. He does business as Thad Danielson Boats in Cummington, Massachusetts.

For copies of the drawings and a table of offsets, contact the author through his web site.

Is there a product that might be useful for boatbuilding, cruising or shore-side camping that you’d like us to review? Please email your suggestions.

It was a thrill to have Thad launch the Mower Dory at the TSCA Meet at the WoodenBoat Show at Mystic last June. All who went for a ride pronounced it fast and fun. I held my breath every time Thad came and pivoted on a dime to dock at Australia Beach. No problem; it handled beautifully. Thad also was good enough to lead a little seminar on his research and build to a spellbound group. Many remarked that it was great to meet someone in 2014 who not only researched an historical small craft but built it and then was so sharing in his relearning how to sail an early traditional racing class boat. Truly an example to the rest of us. Thanks, Thad.

I grew up racing a C.D. Mower-designed 16′ Meteor, which was exclusively a Manhasset Bay class from 1925, created as a junior class. It had a small jib (25 sq ft) but no spinnaker. Even though there were no other Meteors racing elsewhere, the Larchmont Y.C. gave us a class start for race week, where we enjoyed rubbing elbows with other kids from around from the Sound, even though there were no others to race against from other clubs.

We junior sailors ran our class with very little adult supervision following by-laws laid down in 1925 when the class was established, which I believe was unique for then and now.

We paid dues of $15 for the racing months of July and August. A sailing instructor, traditionally elected from among class alumni who had graduated out of the “junior” ranks. The sailing instructor was paid 50% of the class dues, not a bad summer job. Over the years, many Meteor-Class alums went on to become North American class champions and, at least one, an America’s Cup winning crew member. Many others continued to sail throughout their adult lives.

Although we never met, I like to think that Charles D. Mower contributed significantly to the political development of the Meteor Class. In later years I had the pleasure of getting to know Mr. Mower’s son Charlie, who was in the marine construction business out of Riverside, CT.