The Penobscot Wherry from Cottrell Boatbuilding of Searsport, Maine, is based on the Lincolnville salmon wherry, a beamy high-volume boat used to remove salmon from weirs in the days when there was a commercial salmon run on Maine’s Penobscot River. “Wherry” is a nebulous term generally used to describe a relatively light rowboat. This particular wherry has a narrow, flat bottom with lapstrake sides, making it a specialized type of round-bottomed dory. “Bottom board” boats such as this one are found all along the Atlantic coast, both with transoms and pointed sterns; these boats include sea skiffs in New Jersey, tuckups and duckers on the Delaware, Staten Island skiffs, and Great South Bay’s Seaford skiffs. This general hull form is also found inland in Adirondack guideboats. The common element among all of these boats is a flat bottom board in place of a timber keel—a feature that allows the boat to sit upright when pulled up onto a beach or trailer.

all photographs by Matthew P. Murphy

all photographs by Matthew P. MurphyThe shapely wineglass transom tapers down to the garboards and the waterline of a double-ender.

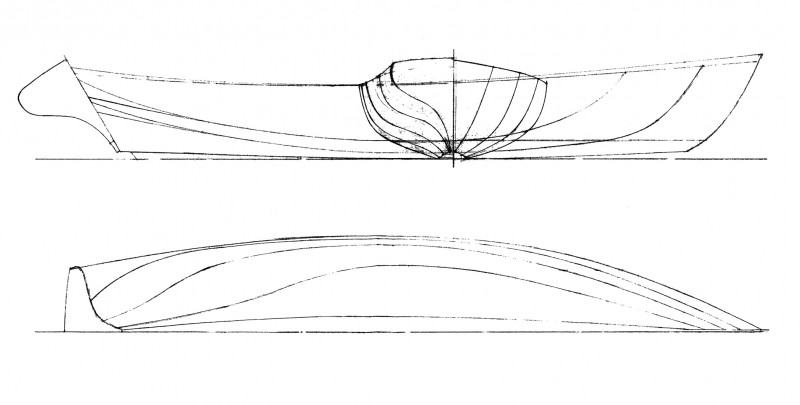

Transom-sterned boats of this family have a narrow “boxed” stern with the garboards coming into the keel at almost 90 degrees, creating a hollow skeg at the stern below the water, and a wineglass shape above. For the Penobscot Wherry, builder Dale Cottrell had naval architect Richard Lagner work up the basic design. The resulting shape is elegant. At the waterline the hull is double ended. A raked, curved stern is both pleasing to the eye and useful in a following sea, lifting much more readily to waves than the squared-off stern of most rowing boats. The rake in the stern is complemented by an easy curved raking stem, a shape that makes it possible to work a little flare into the bow, which helps keep the boat dry when rowing to windward.

A nicely sculpted stem head punctuates the intersection of the curves of the sheer and the stem.

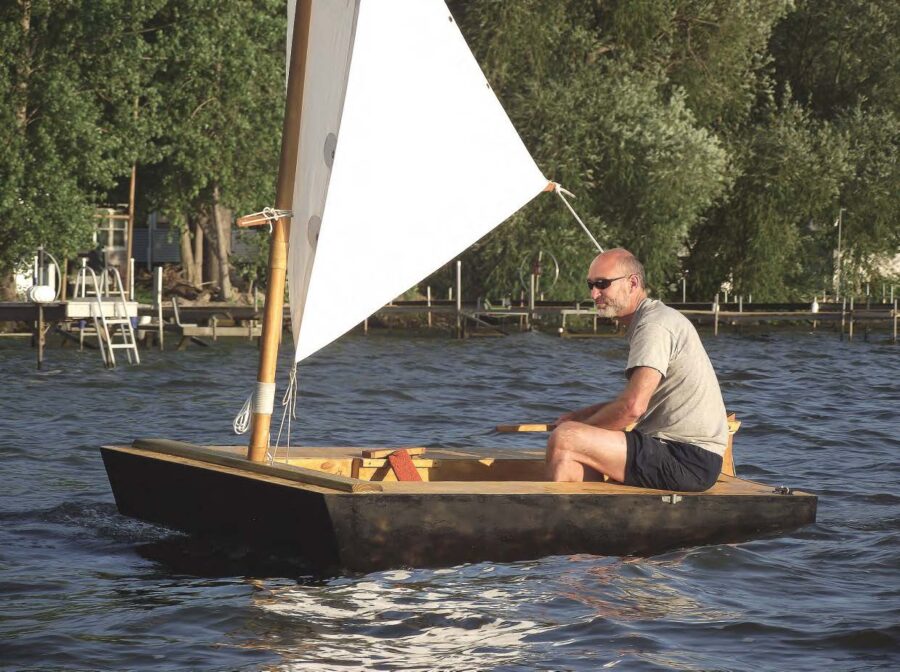

Dale Cottrell likes to build small rowing boats and dinghies. While he can do a fine job of plank-on-frame construction, his boats are primarily of glued lapstrake plywood, which makes them handier for people whose boats live on trailers, as the plywood planks do not shrink and swell with changes in moisture content. This construction also produces a lightweight boat as compared with a plank-on-frame hull. Like the products of most small boat shops, Dale’s boats need to go out the door to customers. The boat we trialed, however, is one of the rare ones he chose to keep for himself and his wife, Lynn. They call her OLIVE. OLIVE measures 15′ with a 52” beam. She is set up with two seats for pair rowing or single rowing with a passenger. The freeboard is relatively low so that 7’6” oars work well at the rowing stations. If someone wanted a single amidships thwart, 8-footers might be needed. Ten nicely lined-off planks per side make the complex shape of the stern and the bit of flare in the bow possible. She has an open interior that could be equipped with floorboards. The seats have a subtle pleasing curve when viewed from above—something I’d not seen before in small boats; they have a stiffener fastened to their undersides. OLIVE has fixed stretchers set up to catch the rowers’ heels. Amidships, the section is veed for about four planks going out from keel, then curves smoothly up to the gunwale. This provides stability when heeled but a lively feeling when rowing. The boat reminds you to sit in the middle, but provides plenty of stability when you slide to the gunwale. As with most fast rowing boats, stepping into the middle and grabbing the gunwales when boarding is a good idea. Fifteen feet is a great minimum length for a fixed-seat rowing boat. Any shorter and there is not much benefit rowing with a partner. Here two can have a fine row and there is nice power when there is wind. Customers have set up their Penobscot Wherries with a sliding seat for more leg power, but this is not ideal for this boat—it pitches with the rower’s weight moving back and forth. This is a fixed-seat boat, at heart.

The glued-plywood lapstrake construction creates an interior that is uncluttered and easy to maintain.

We’d planned for a still and clear early morning to test OLIVE, but got only some of that. It was a clear early July morning with great light, but we were served with a stiff northwesterly breeze running down the mile or so of harbor, kicking up a chop with the odd whitecap. It gave us a good chance to test the boat in conditions where many rowers might stay ashore, breezy enough for testing the reefing gear on a small sailboat. It was a great day to see how the boat handled in the wind.I first tried some laps with tight turns. This demonstrated how easily she spins—and indeed she spins quickly. She sits lightly on the water, so only a few strokes are required for a 180-degree turn (as compared to plumb-stemmed, straight-keeled Whitehalls which have a much wider turning circle). Dale then joined me, rowing stroke, to see how she behaved with two aboard. Which brings us to the matter of trim ballast. Small rowboats really benefit from trim ballast. The problem is that when a boat is set up to trim level for pair rowing, if rowing single the bow or stern is high depending on the seat chosen.

Reviewer Ben Fuller takes the Penobscot wherry out for a solo row with some ballast in the bow to keep the boat in trim.

For the trial Dale picked up a large beach boulder and put it in canvas bag. Not knowing that, I had a soft five-gallon water container with me, which is what I usually take along in my larger dory. When rowing single from the after seat, I’d slid the stone ahead of the forward seat. With Dale aboard, we tucked the rock under him, as I’m a bit bigger. Doubling the power with the same windage made pulling into 15 knots or so of wind seem like rowing into a light breeze. As expected, with two aboard, and the boat deeper in the water, some coordination was needed for a quick turn.

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyWith two at the oars, the wherry wasn’t significantly slowed by a 15-knot headwind.

Then I took her out for a solo spin around the harbor. Surreptitiously, I’d slid my GPS onto my rowing thwart. First I went downwind—the easy way—and was hardly working while running at an easy 4-plus knots, surfing wind waves. Thoughts of a couple of drybags of gear and Islesboro and an island campsite a dozen miles to leeward crossed my mind. With my weight in the stern seat and the ballast stone under the bow seat, she was quite well behaved going straight without wanting to turn up into the wind. Coming back was more work, but a steady pull into the teeth of the wind gave me better than 2 knots. I slid the ballast rock quite far forward to trim the bow down. Perhaps most interesting was rowing across the wind, which is where many rowing boats will misbehave. Three knots was easy, but what impressed me the most was the ability of the boat to stay on a straight line without needed hard pulls on the windward oar—something that is often the case. In big dark puffs, the boat just slid sideways a little. After I gave OLIVE back to Dan and Lynn, they jumped in, pulling well together upwind. My last sight of them that day was their turning around after a mile upwind to the head of the anchorage. If I were not overequipped with boats, I’d add this one to my to the fleet. She is great for anchorage and estuary cruising, poking up narrow coves, or heading across a broad harbor. Her flared bow and raking stern keep the water out if a sea is running. Her size is ideal: light enough to be easily maneuvered onto a beach or light trailer but capacious enough for two or three on a picnic. Dale could put a sailing rig in her, but I’d not bother with this as she slides along nicely without one under oars alone. While a competitive racer might seek a longer boat, this wherry is about as big as one might want for solo recreational rowing. A foot or so longer and narrower would be faster, but at her current size, the low wetted surface makes her an easy pull, a boat that you can row faster than you can walk, all day long.![]()

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, has been messing about in small boats for a very long time. He is owned by a dozen or more boats ranging from an International Canoe to a faering.

Penobscot Wherry Particulars

[table] Length/15′

Beam/52″

Weight/125 lbs

[/table]

Finished boats are available from Cottrell Boat Building, 285 Mt. Ephraim Rd., Searsport, ME 04974; 207-548-0094; www.cottrellboatbuilding.com.

Is there a kit one might buy ? Are there plans or is the boat only available for purchase and if so, how much is it? Thanks.

We checked with Cottrell Boatbuilding and received this in reply: “The Wherry is only available as a finished boat and it starts at $9459 and goes up depending on the different trim packages and extras.”

Christopher Cunningham, Editor

Beautiful lines on this rowboat

Reminds me of the beautiful Annapolis Wherry by CLC. They make a single and a double in kit or plans. Not a rower myself but the lines of these boats can make me want to convert. Floating sculptures.